Kronos Quartet

Infinite Horizons

by Anil Prasad

Copyright © 2014 Anil Prasad.

Kronos Quartet’s transformative influence on the worlds of classical and new music is nothing less than remarkable. The group, which is celebrating its 40th anniversary, has broken every boundary imaginable, redefining what it means to be a string quartet. Comprised of David Harrington and John Sherba on violin, Hank Dutt on viola, and Sunny Yang on cello, Kronos’ output straddles and often bridges a multiplicity of genres. World music, jazz, pop, rock, electronica, industrial, noise, Beat poetry, and folk are among the universes Kronos has fearlessly integrated into its work.

The San Francisco-based group has collaborated with many renowned composers, having commissioned more than 830 works from the likes of John Cage, Morton Feldman, Philip Glass, Osvaldo Golijov, Henryk Górecki, Sofia Gubaidulina, Astor Piazzolla, Steve Reich, Terry Riley, and Aleksandra Vrebalov—just to name a handful. And their interpretations of works by composers and artists as diverse as Bartók, Shostakovich, Charles Mingus, Thelonious Monk, R.D. Burman, and Jimi Hendrix offer original takes on classic repertoire.

It’s an understatement to say the group’s far-reaching explorations have significantly expanded the audience for classical music. Early on, Kronos was also known for breaking out of traditional classical garb and opting for urban street attire—an approach that became widely adopted among many other classical ensembles. Today, a typical Kronos audience crisscrosses every age, ethnicity and economic stratum. Unquestionably, Kronos made the string quartet accessible for generations of listeners.

Another distinguishing feature of Kronos is its focus on unique partnerships. Highlights include recordings and performances with Laurie Anderson, Asha Bhosle, David Bowie, Zakir Hussain, Wu Man, Paul McCartney, Modern Jazz Quartet, Tanya Tagaq, Amon Tobin, Vân-Ánh Võ, and Tom Waits.

Innerviews met Harrington at Kronos’ studio and office space located in San Francisco’s Inner Sunset District. Several big picture conversations across two years examined the group's vision, origins, motivations, and current directions. Although the environment is relatively straightforward and unadorned, one gets a sense of the magnitude of the quartet’s accomplishments when walking around. Photos of Kronos with the Dalai Lama and Philip Glass, along with an array of recording industry awards, welcome visitors. Staff work on bookings and organizational activities. A huge archive of Kronos recordings and sheet music numbering in the thousands occupies several rooms.

The interviews were conducted in the rehearsal room, set up exactly as the group is positioned onstage. Harrington, typically clad in denim, an unbuttoned long-sleeve shirt over a t-shirt, and sneakers, always sat in his first violin chair, with Innerviews in Sunny Yang’s cello seat. In the corners, all manner of auxiliary instruments awaited their next assignment, including an Omnichord, Stylophone, a bass drum, and even a vintage Simon electronic game, whose sounds the group has since incorporated into a piece. With casual grace and in a precise, soft-spoken voice, Harrington provided unprecedented insight into the incredible journey Kronos has experienced to date.

Innerviews also spoke with Terry Riley, Aleksandra Vrebalov, Vân-Ánh Võ, and Janet Cowperthwaite, Managing Director of the non-profit Kronos Performing Arts Association. Their perspectives on working with the quartet follow Harrington’s reflections.

Kronos is much more than a quartet. It’s a platform for cross-cultural, cross-generational collaboration. What’s your perspective on that idea?

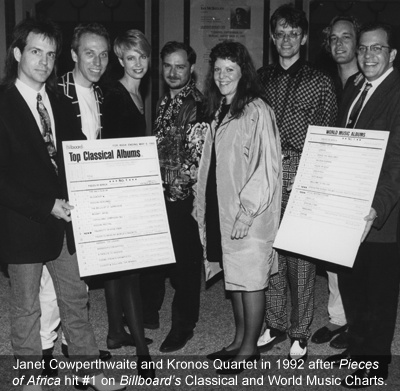

I agree. I’ve always wanted that for our music. Quartet music is more than four people. In addition to the musicians, it involves the composers, publishers, recording engineers, luthiers, record companies, presenters, publicists, and the audience, just to name a few. It’s a community of music lovers. One of the things we do with Kronos is establish long-term relationships with wonderful, creative people, including many composers and other performers. Our manager, Janet Cowperthwaite, has been with us for 33 years. Another long-term relationship is with Terry Riley, who has written 16 or 17 pieces for us since 1979. We’ve been working with Tanya Tagaq for almost 10 years now. Laurie Anderson wrote a major new work for us. We’re also doing new pieces by Nicole Lizée and Aleksandra Vrebalov. We don’t take these relationships casually. I feel the work improves with time, experience, and trial and error. It takes practice and involves asking “How do we adequately reflect the work?” I constantly think about that.

What qualities do you look for in a collaborator?

What I need from music, and what I feel my family, friends and audience need, are vibrant, indelible musical experiences. So, I’m looking for those rare people who can help provide those. There are a lot of composers and performers in the world. All I can do is use my own sense of what magnetizes me, personally. I think it’s safe to say that if we got into a collaboration, it’s because something intrigued me about the person, their work, their instrument, and the possibilities.

I don’t have a set way of approaching things. For instance, when we were on tour in Rotterdam in 2012, after the concert, the presenter said “You know, there’s this composer I’ve heard named Santa Ratniece. She’s written this amazing choir music. She’s from Latvia. I don’t even know if she has an email address, but I’ve listened to the music and you should hear it.” He handed me some recordings and I went back to the hotel and played them. I could not believe what I was hearing. I wrote to him that night and said “I have to find out how to reach this composer, because I believe she can write a great piece for Kronos.” That’s the same kind of criterion I’ve used for 39 years.

The first piece written for Kronos was "Traveling Music" by Ken Benshoof in 1974, which is available on our 25 Years box set. He was my composition teacher when I was in high school. One of the reasons you and I are sitting here talking is because that piece was so fantastic and so much fun to assemble. By the time we got to the world premiere and were on stage performing it, "Traveling Music" felt like our music. We felt we had such a personal involvement in making it. It didn’t feel like something I would buy from the music store or something that was transferred to us over the centuries. It felt like something we were all directly involved in. We were reading off the manuscript and we worked in Ken's home. We knew his voice and his ideas, and made a lot of changes during the rehearsal process. By the time it was ready to go, it belonged to us. That’s very important, in my opinion.

Many of your collaborators are from diverse global cultures. How do you internalize the intricacies of these musics so you can engage in a full-blown dialog with the artists?

First of all, I try to gather as much information as possible. Let’s use Vân-Ánh Võ as an example. When I first met her, we began talking about Vietnamese culture, music and life. That’s how it really began. I said to her “I started Kronos in 1973 to play ‘Black Angels’ by George Crumb.’” I gave her our recording of that piece and said this music came out of the American war in Vietnam. At the time, I was a 23-year-old musician and very confused by what was happening in the world. I was angry. I felt America was destroying itself, as well as another culture, people and environment. I thought it was awful. I felt quite removed from the news I was seeing on television and reading in the newspaper until the summer of 1973 when I heard “Black Angels.” All of a sudden, I had a voice. But in order to use this voice, I had to be in a group that would be able to play that music. So, in September of 1973, I started Kronos. The reason was to have some way of responding to that awful war. In the years since, I’ve wanted to find ways of expressing some of the sorrow and feelings of being paralyzed by these events. I felt so much of life did not adequately confront the issue. I wanted our work to bring it front and center. I wanted to deal with it and try to change the balance, if possible.

So, Vân-Ánh and I kept talking every few weeks for about a year, until there began to be a piece. We didn’t know quite what it was. There were a lot of things I wanted in it and a lot of things she wanted in it as well. It became this collaboration, and eventually, it included elements she could notate for us and describe. We began to rehearse and the piece came out as more of a theatrical work than a concert piece in which all the notes were finely etched into stone. So, there was a lot of learning that went into that—learning how to speak to each other, learning how to provide each other with the kind of information needed to do what we were trying to do. Eventually, we arrived at “All Clear.”

That process is basically the same one we’ve followed with every other relationship. The differences have to do with different musicians’ personalities, the way he or she might relate to the group, the instrument or instruments our guests might bring to the work, the kinds of demands made of us, and what we have to learn. It's an instinctual thing. A lot of what I do is about trying to know when the right moment is for a person to write for us. I’ll find an idea that seems like it’s the right one and it triggers something inside of me. I’ll realize it’s something I want in our work and for our audiences.

After 9/11, Kronos engaged in a lot of repertoire and collaborations that served as commentary on the state of American foreign and cultural policies. You were also very overt with your own perspectives at some of the shows, particularly during the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003. Provide some insight into the idea that the personal is political for Kronos.

I think everything is personal. Everything is also political, in that every decision you make expresses something of how you want the world to be. That especially holds true for string quartet music. I can point to “Different Trains” by Steve Reich. Four quartets were playing: one live and the other three pre-recorded. There’s all this technology involved. There’s also the research that went into finding the voices of survivors of the Holocaust, and the sirens and horns from Europe and the US. When all is said and done, it’s a very personal piece. That’s what I want from our composers. I want to hear the sounds from inside them. Sometimes it’s hard to locate that sound. It’s a conversation I have with people all the time. There’s so much noise going on in the world—so much activity, confusion and so many expectations. How do you actually hear the innermost sounds? I’m not sure I know, but I know for myself that it doesn’t happen all the time. It’s very rare. It’s those rare moments that I want as part of our work. When I’m searching for new things, I’m on the lookout for that special quality.

The reason I said everything is personal is that in January 2003 I first became a grandfather. Shortly after that was the buildup to the invasion of Iraq. I felt again like I did during my late teens and early 20s. I recognized it. In March of that year, despite being ecstatically happy I was now a grandfather, there was this counterbalance pulling me down. There was this dread of “What is my role? How can I help protect this little person?” I went through a serious depression and didn’t even talk to the rest of the group about it. I just felt hopeless and I lost track of the reason for being away from my family six months a year. Finally, I decided to think of all the great voices I had heard in my lifetime. I settled on the one who made the most sense to me and that was the voice of Howard Zinn, the American historian. My friend, David Barsamian, had Howard's home number. I got it from him and it was one of the few times in my life I just called someone’s number like that. I once had the phone number of I.F. Stone, the great American investigative journalist, in my pocket for years. I didn’t know what I could say to him. By the time I did, he was very ill and then he died the day we recorded “Black Angels.” I said “I’m not making that mistake again.” So, I called Howard and his wife Roslyn answered the phone. I told her who I was. She said “Oh, Kronos. We’ve listened to Kronos for 20 years. Howard will be home in an hour and he’d love to talk to you.” An hour later, I called him back and a month later I was in his office. My question for him was very simple: “What can a normal person do in this time?” Howard took an hour and explained it to me. His answers were very simple and afterwards, I thought “I now have enough confidence and energy.” Before that, I was lost.

What were some of his answers?

Some of the things he said that resonated include:

“Use whatever platform you have to make your viewpoints very clearly known. You can’t do anything by yourself. Build a community.”

“Have conversations frequently. Share your ideas. Things tend to radiate.”

“Powerful people are afraid of artists, because they go beyond conventional ways of thinking and known structures. Use that fear to your advantage.”

Howard and I became friends. Eventually, Howard appeared with us at Carnegie Hall as part of a program we called “Alternative Radio,” as well as in Vienna at the New Crowned Hope Festival. At Carnegie, we did two one-hour radio programs. Howard was interviewed by David Barsamian and Kronos performed the live music. For me, there was life before that night and life after that night in terms of our work. I was ecstatic after that. Howard was talking about war, about music and what people can do. I’ve always by nature wanted to bring the world into our work—the world as we tend to know it, as well as the world as we can imagine it for the future. I don’t want the music of Kronos to be antiseptically treated so there’s a little no-man’s land around it in which everything is safe and preserved. I want our music to deal with the way things are.

In order to do that, we have to be cognizant of suffering, environmental degradation and injustice. There are a lot of things we take for granted, including the safety that we have in order to play music. You and I are very lucky, right now, in that we can sit here and talk without having bombs falling around us. I want to take advantage of that safety I have and the opportunity that emerged when I was 12 and first heard string quartet music. Very shortly after that, I decided that I was going to be a musician. The decision was “The world’s just going to have to get used to me being a musician.” [laughs] I didn’t care what I had to go through to do it. That’s why it was such a big problem for me when I said I felt there was this undertow that was pulling me down and I didn’t know how to get out of it. I have Howard to thank for getting me out.

You once said “I’ve always wanted to play bulletproof music that protects people from suffering and shields children from harm.” Elaborate on that.

I’ve thought about wanting bulletproof music for years and years. Wouldn’t it be great to create a musical experience that could put its arms around a little child and protect that little person's family?

By instilling ideas and inspiration?

Hopefully. I haven’t given up hope that we will be able to create that kind of musical situation or statement. We haven’t done it yet. In every conversation I have with a composer, I’m challenging them and Kronos to try and create that kind of experience.

You worked with Noam Chomsky when Kronos participated in the 150th anniversary of MIT during 2011. Describe how that experience unfolded.

I said to the organizers “When I think of MIT, I think of Noam Chomsky. The only way we can do it is if we get him involved.” I’m astonished by his honesty and attention to detail. He can tell you the time events have been reported in the New York Times for decades. He can tell you the page numbers of books and newspapers. The mind the man has is unbelievable. He also concentrates on actual facts versus what’s reported in the media.

I first met Noam Chomsky at Howard Zinn’s memorial service. I was introduced as “David Harrington of Kronos Quartet.” I thought “What am I going to say to Noam Chomsky?” So, I shook his hand and he smiles and looks right into my eyes and says “Can you tell me about the Russian school of violin teaching?” I said “I can tell you a lot, actually.” [laughs] When I was 15, my teacher was Emmanuel Zetlin, who studied with Leopold Auer in the same class as Jascha Heifetz, in St. Petersberg. That is the Russian school of violin playing and teaching. Then Noam tells me about his son playing violin and how he had a Russian teacher. And that’s how our relationship started.

When it came time to do the event, we didn’t have a chance to rehearse with him. He was too busy doing interviews and writing. But I had a meeting with him the morning of the concert. I said “Noam, my idea is that it would be great if you could tell our audience about your involvement with music and how music might be a way towards activism as a way of life.” I had heard an interview with him shortly after his wife died. They had been married for many years. They went on their honeymoon several years after they got married, when they finally had enough money to go to Europe. Noam talked about being at the Prades Festival in France. Pablo Casals had left Spain in objection to Franco. So, he started a festival across the border in France. Noam and his wife went to hear Casals play Bach’s “Cello Suite No. 1.” We musicians use our ears and I could hear the change in Noam’s voice when he described the influence of that experience. I thought “Wow, maybe music did something for him. Perhaps it answered questions or gave energy to him.” So, I asked Noam to talk about that. Tod Machover had written a piece titled “Chomsky Suite” that would be played in four movements, inspired by Bach’s “Cello Suites.” We chose to have Noam speak over it, discussing his experience at the Prades Festival and what music meant to him. He discussed how Casals wouldn’t play in fascist countries, which was a form of activism in and of itself. Noam also discussed his brief time as a guitarist in a pickup band. In addition, he talked about how music helps us “aim for something higher than that which we do regularly, expertly.”

In the little time we had in his office to talk before the performance, I decided to have a little rehearsal moment. I said “I’m going to hand you an instrument. I’ll show you how to play it. If you watch me during Terry Riley’s ‘Cusp of Magic’ before your piece, you’ll see how to do it.” He agreed to do that and you can see it on YouTube. I had this little orange violin I picked up in Mexico. I handed it to Noam and he started to play it. Well, he didn’t even make a sound. He’s a very gentle person. He speaks very quietly. You have to mic him to hear him. So, I said “Noam, you have to dig in.” He tries to dig in and he makes a little sound. Then I said “You really have to dig in!” And he starts digging in more. Pretty soon, I realized Noam was actually enjoying himself and he’s a bit of a ham. [laughs] That broke the ice and the experience at that concert was wonderful.

Kronos did the soundtrack for the film Dirty Wars. What drew you to scoring it?

Dirty Wars follows the investigative journalism of Jeremy Scahill, who has a book out by the same name. The topic is the American drone attacks in Somalia, Yemen, Pakistan, and Afghanistan. If you listen carefully to some of President Obama’s 2013 speeches, he’s pretty much responding to Dirty Wars. When I first saw the film, I felt sorrow, shame and fear for my daughter, son-in-law, grandkids, and the future. A country can’t do what we’re doing and get away with it for long. Eventually, there will be drones from other countries coming to our country. That’s all there is to it. I’m a violinist, but I can tell you with certainty that once something like that exists, other people will find ways to use it. Once innocent people are killed, it creates much hatred and anger aimed at this country. Most of us didn’t even know this was going on until recently.

When I saw the film, it took me back in a sonic way to the very first chord I ever heard of string quartet music, which was from Beethoven's “String Quartet in E-flat Major, Opus 127.” The chord I’m referring to was turned into E-flat minor, though. There’s a big difference. The chord resonates in a weird way inside of me. So, I got out the score to the Beethoven piece and looked at the spacing and the way he orchestrated the chord to get that sound. It captivated me when I was 12-years-old. It occurred to me that Kronos could retune a set of instruments to play this chord for the film. We had to rent instruments, because there was no way we could alter our instruments that significantly. It would damage them. But I wondered what would happen if we played those tones on open strings, with the other strings we didn’t play serving as sympathetic strings. So, that’s what we did. We went into the studio with an altered tuning that had each musician playing the E-flat minor chord that Beethoven wrote for our instruments. We created 120 variations of that chord for the film. They also used a number of our tracks from Floodplain and right near the end is our recording of the second movement of Vladimir Martynov’s “Schubert-Quintet (Unfinished).”

Reflect on the importance of Terry Riley to Kronos.

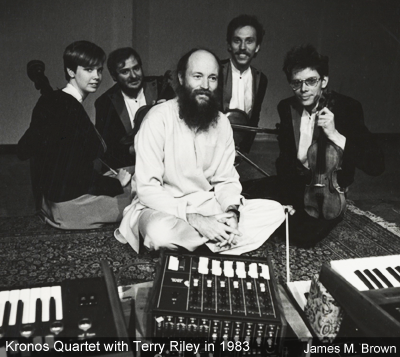

I can’t even imagine the work of Kronos Quartet across the last 35 years without the music of Terry Riley. Terry’s work has been absolutely central to our concerts, as well as the underlying meaning of what we’re communicating in a lot of our work. Terry is also one of the most generous musicians there is. He introduced Kronos to his great teacher Pandit Pran Nath, Hamza El Din, La Monte Young, Jon Hassell, Zakir Hussain, and the list goes on and on. All of those composers have written for us.

Speaking specifically about Terry’s music, we first met at Mills College in 1979. Kronos was rehearsing “Traveling Music” by Ken Benshoof and Terry came into the concert hall and sat down and listened. Later, when we took a little break, I met Terry. He was introduced to me by the late Sally Kell, who was a wonderful cellist on the faculty at that time. It turned out that Ken and Terry went to San Francisco State together in the ‘50s. Terry had never heard any of Ken’s music until he heard “Traveling Music.” Meeting Terry was a beautiful experience. Right away, I felt this man was a quartet composer. There’s something about his generosity of spirit that made me think “I want this man’s music in our work.”

It took about a year of phone calls, letters and meetings for me to convince Terry that he should write notated music. “In C” was the last notated piece he wrote before composing “G-Song,” “Sunrise of the Planetary Dream Collector” and “Remember this O Mind” for Kronos. The idea of notating his music had vanished because he was totally into North Indian raga singing and improvisation. I think he felt that would be the trajectory he would probably remain on. So, it took a little bit of counterbalancing to move things in a different direction. Eventually, he didn’t write one piece, but three. That’s what I mean about his generosity.

We played his music together with him. He did “Remember this O Mind” with us as keyboardist and vocalist back in 1980. Before that, we went to his ranch and stayed there a couple of days. We rehearsed in his music room. It was so much fun. He kept imagining a certain sound and we didn’t get it at first. It took quite awhile. It was a year or so before I felt Kronos arrived at the sound we were all looking for. It happened when we were playing “The Wheel,” which is the introduction to one of Terry’s other pieces for Kronos. The sound had no vibrato, yet had to be really expressive. It was like we were using our bows in a painterly manner. It felt like a whole new way of working. I could feel things clicking into place. Terry has worked with us on rhythm for years as we search for the pocket of the beat. He’s a master of that. If you go back and listen to the albums Cadenza on the Night Plain or Salome Dances for Peace, you’ll hear that there’s something in his rhythms that he’s written for Kronos that are just so beautiful and unparalleled in quartet music. The rhythmic tapestry of "Salome Dances for Peace" contains some magical moments harmonically, rhythmically and melodically in every way you can think of. It’s such an amazing masterpiece.

For me, Terry is like a musical Howard Zinn figure. He challenges without being abrasive. The energy that surrounds him makes you want to do better than you did before. It’s part of his being. I love the man and the contribution he’s made, not just to Kronos’ music, but to all of Western music. He’s absolutely unbelievable. He’s a true leader and he does it by listening to his inner voice.

“Sun Rings” is a highlight of your collaborative output with Riley. Describe how it came together and its importance to you.

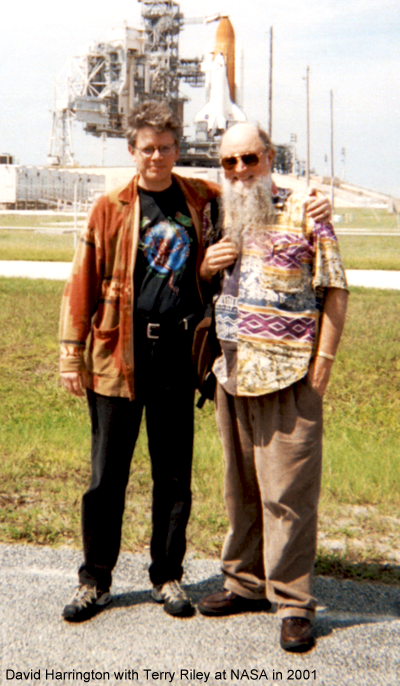

We got a call from NASA’s Arts Program director Bert Ulrich in 2001 and his question was “Would you be interested in including some of the sounds recorded on the Voyager expeditions in your concerts?” I was in Europe at the time and Janet Cowperthwaite sent me the message. I thought “Well, I didn’t know there were any sounds out there. I’ve got to hear these.” Eventually, we got this cassette tape—yes, a cassette tape, believe it or not—from NASA, and I heard it and thought “This is amazing. I know the composer we should use to bring these sounds into our work and that’s Terry.” I told myself “I want to do this and I want to be there and see the look on Terry’s face when he first hears these sounds.” As it turns out, we were recording the album Requiem for Adam at Skywalker Sound, and that’s when I asked Terry about the idea and first played him the sounds in the control booth. That was the spark that got this piece going.

Eventually, we wound up in the office of Don Garnett, the astrophysicist at the University of Iowa and inventor of the plasma wave receptor that’s been on all of the NASA flights. We discussed the sounds and the project. Terry and I also attended a NASA launch to check out the vibe and also learn about the whole political dimension of NASA. Was it something we could feel good about being a part of? We wanted to figure that out.

Once we decided to proceed, Terry wrote “Sun Rings,” and as has been the case with all of our work together, Terry had some big ideas for it. With “Salome Dances for Peace,” Terry said “This piece is getting a little longer. I think there are five quartets here.” [laughs] “Salome” ended up being about two-and-a-half-hours long. For “Sun Rings,” the call was “You know, I think there needs to be a choir on this.” I said “How big?” Terry said “Around 40-50 voices.” I thought “Oh no!” [laughs] Then a week later, he said “I think there needs to be a visual component.” So, eventually, we got Willie Williams onboard. Willie has been the stage designer for U2 for the past 30 years. The choir has been one of the great parts of the piece. Wherever we play “Sun Rings,” whether it’s Australia, Scotland or Korea, there’s a community that surrounds the piece. In general, Terry creates a community wherever he goes and wherever his music is played.

Riley’s “Requiem for Adam” is the most personal composition you’ve been involved in. Tell me about the circumstances that led to that piece.

There were four major tragedies that hit Kronos. There was the death of Hank’s partner Kevin Freeman from complications related to AIDS in 1993. We all loved Kevin enormously. The next year, Larry Neff, our lighting designer, lost his brother Julian in a motorcycle accident, and Joan Jeanrenaud, our cellist at the time, lost her baby Mario Moruzzi, who was stillborn. In 1995, I lost my son Adam. I saw my child die right in front of me on Easter Sunday, April 16, 1995 at the top of Mount Diablo.

After that happened, I couldn’t even think about being a musician without feeling the effect of that loss. Adam’s death changed the way I hear, what I needed from music, and what I wanted to present. I’m not even sure I can explain it. I can hear it, though. For me to even be able to get on a stage again took the help of so many people and so much music. The quartet, Janet Cowperthwaite, our record label Nonesuch—every member of our community helped me and Kronos at that time. This meant everything to me. I will always be grateful for their help and support. I will spend the rest of my life trying to deserve it.

We were assembling the Early Music album during that period. You can listen to that album and look at the titles to have a glimpse of my thoughts. The Schnittke piece “Collected Songs Where Every Verse is Filled With Grief” and the bells at the end are particularly important. I listened to over 300 examples of bells to find those we used. I needed a certain sound that I had heard in my lifetime, but I didn’t know where I would ever find it again. John Kilgore sent me hundreds of kinds of bells and I found the ones that had to be on the album.

Basically, there was a trilogy of albums that started with Early Music. The sound of that album was as close as I could possibly come to expressing the sound that I eventually heard inside. For what seemed like an eternity, there was a vast silence. Then, on September 16, 1995, which is Adam's birthday, I was in Seville, Spain. As the poet Federico Garcia Lorca said, “In Spain, the dead are more alive than the dead of any other country in the world.” So, there I am on my son’s birthday and I was in a record store and all of a sudden “Gloomy Sunday” by Billie Holiday came on. I had heard it before, but all of a sudden the idea for the Caravan album just happened. It was at the same record store where I picked up a CD of gypsy string orchestra music. It was great because of some of its incredibly powerful notes. I’m a great believer in notes. I make notes. It’s what musicians do. We try to put as much of what we know, what we intuit, and what we desire into our notes. And there are some great notes that people have made. On this particular album, there were some notes that were so sad I couldn’t believe it—especially on that day. Later, when I listened to the album again, the notes sounded happy. I thought “Kronos has to explore this area.” And that exploration became the Caravan album.

The first Christmas after Adam died, my family visited Mexico. I had been to Mexico before and I realized there is something about the way death is expressed, permeates the culture, and is celebrated there that made it essential for my family to be there at that time. We went for 10 days shortly before Christmas through New Year’s. Basically, every sound on the Nuevo album is something my family and I got from that experience.

You’ve said the trip saved your family’s life. How did it do that?

I do feel it saved us. There were points when we felt we couldn’t make it anymore. The trip gave us perspective. It brought us closer to Adam. I will always have immense gratitude to the culture of Mexico, the music, the people, the sounds, the food—everything. When I hear this political crap that’s going on as it relates to Mexico, it really angers me, because my feeling about that culture is that it’s so deep, beautiful and expressive. The balance of life and death is expressed so poignantly.

Getting back to Terry, he asked me “Would you be interested in having three requiems for Kevin, Mario and Adam? Would this be a good thing?” Terry knew Adam very well. Adam’s birthday, September 16, is also Terry Riley’s son Gyan’s birthday. We shared several September 16ths together. I brought up the idea with Hank and Joan and we all wanted to make them happen and I told Terry “It would be a wonderful thing.” In addition to “Requiem for Adam,” which was released on the album of the same name, Terry’s “Lacrymosa: Remember Kevin” is also recorded. It just needs a little more editing and it will be ready to release. The piece for Mario has not been recorded. I should mention that Ken Benshoof also wrote beautiful pieces for Kevin, Mario and Adam. Ken's incredibly poignant viola solo “Song of Twenty Shadows” is recorded on the 25 Years box set.

What I've learned about loss is it's like a delayed depth charge that will go off and you never know when. After Adam died, there were several weeks when even holding the violin was something I couldn’t even think about doing. Eventually, it was determined that there was a concert a month after in Orange County and that I would try to play it and see what happened. There was a point when we rehearsed for the first time after Adam died. John, Hank and Joan asked me what piece I would like to play first at that point. I realized I wanted to go back to the very beginning and see what it would feel like. So, I said I would like to play Ken Benshoof’s “Traveling Music.” I tried to play it and it felt so weird. My sound didn’t sound like my sound because of everything that was going on inside of me. John, Hank and Joan were so supportive and kind. Fast-forward 18 years. Sunny Yang, Hank, John and I were playing “Traveling Music” for the first time since 1995. I couldn’t for the longest time figure out what was so weird about playing it. Sunny played it so beautifully and it felt like something we all knew. She had been studying our recording a lot and we were finding new ways of playing it. It was great, but there in the middle of it, I realized “Oh my God, that’s the first piece I played after Adam died.” I almost lost it. I didn’t even know what to say to everyone at that point. I never know when I’ll feel this staggering loss.

Pandit Pran Nath also played a significant role in your life after you experienced this tragedy.

One of the deepest experiences of hope I’ve ever had in my whole life was when Pandit Pran Nath came to our home the Sunday after Adam died. He didn’t say a word to me. He just came up to me and hugged me for a very long time—it could have been an hour. It was so optimistic and generous of him. Pandit Pran Nath died the year after Adam in 1996. By that point I heard Terry’s Lisbon Concert album, a solo piano recording, which is great. I said to him “You should do something on our album.” We were at Skywalker Sound with him and I said “Please think about Pandit Pran Nath and just make a piece.” It became Terry’s piano track “The Philosopher's Hand” that closes the Requiem for Adam album.

Tell me about the new Philip Glass commission, “String Quartet No. 6.”

It’s a major new work. It’s thrilling to play. The piece has the mastery and confidence of years of experience combined with a propulsive force that is fun and engaging. We’re all very pleased with it. It’s incredibly difficult to perform. My part is exceptionally challenging. My wife Regan heard me practicing day and night on it. She said “Why do you have to practice so much? Haven’t you learned to play already?” [laughs] This piece pinpoints things I should have worked on when I was a kid. If I had practiced in a better, more complete way when I was 12, instead of playing quartet music all day and night, it would have been easier for me to play the piece.

Philip said he tried to write the very best piece he’s ever written. That’s what I hope for from every one of our composers. I love it when people try to raise the bar. That’s what I want to do with our own work—make every note better than the last one I played.

It would be hard to imagine contemporary music without Philip Glass. His output is incredibly vast. I saw Satyagraha recently and it blew my mind. I was totally thrilled. I’ve also seen Einstein on the Beach in recent years, which is also incredible. I also love the social conscience that’s a part of Philip’s work. Something that’s not so well known is Philip’s generosity to younger composers. He provides comments and pointers about the work of a lot of young composers. It’s really admirable. He’s a very large figure in American culture and we’re really lucky to have him.

Steve Reich is another major composer that has been pivotal for Kronos. Describe the influence he has had on the group.

Steve wrote “Different Trains” when Joan Jeanrenaud was in Kronos. He wrote “Triple Quartet” when Jennifer Culp was in the group. And he wrote “WTC 9/11” when Jeff Zeigler was with us. It’s hard for me to even imagine the trajectory of our work without Steve. “Different Trains” totally changed everything for Kronos. Steve wrote a piece that brought the voices of survivors of the Holocaust into the concert hall. It changed what a Kronos concert could be, back in 1988.

We were using a reel-to-reel tape as a backing track for “Different Trains.” I’ll never forget a performance of that piece in Nebraska, because the tape began to slow down ever so slightly over a period of 28 minutes. [laughs] We could all tell it was happening and we had to adjust our intonation all the way through. We’d often show up at concert halls and have the person who operated the sound system have no idea what to do with the piece. It became clear that Kronos had to have its own dedicated sound engineer after that. Since 1989, we’ve been a totally magnified group that has toured with our own engineer. We hold very extensive sound checks. Our engineers know all of the pieces that have any sort of altered quality, backing track or effects. The engineers have become part of the extended group and that’s directly a result of touring “Different Trains.”

In general, Steve’s music has had an incalculable effect on us and opened up a lot of things for a lot of composers. It became possible to do Scott Johnson’s “Cold War Suite” with the voice of I.F. Stone, and Michael Daugherty’s “Elvis Everywhere” and “Sing Sing: J. Edgar Hoover.” Sofia Gubaidulina heard us play “Different Trains” and “Purple Haze” at the Concertgebouw in Amsterdam. It led to what she did with “String Quartet No. 4” for us. I could go on and on about what resulted from “Different Trains.”

Steve initially had several ideas up for consideration for Kronos. One was the idea of using voices of the Holocaust and the other one was using Bartók’s voice for a piece. I said the voices of the Holocaust was the one it should be. I’ve always wanted composers to find a personal aspect to amplify their work for us, and that seemed absolutely right. Ten years later, I called Steve again. I had no idea if he would want to write another piece for us after “Different Trains,” which was his most personal piece and a true groundbreaker. I wondered what it would be like for him to try and come back to this form. He jumped at the opportunity immediately. By then, we had recorded Alfred Schnittke’s quartets, so Steve’s “Triple Quartet” is influenced by Schnittke and Bartók, as well as klezmer music.

Ten years after “Triple Quartet,” we discussed the idea of another piece. I remember asking “Could you imagine a bookend for 'Different Trains?’” At that point, it was 20 years later. Somehow the idea came up about September 11, 2001. Steve’s family was directly affected. His son, daughter-in-law and grandchild were just blocks away from the twin towers. Steve and his wife Beryl were outside the city that day. Everyone was ultimately okay, but there were many hours when they didn’t know. Just the sheer terror that gets imprinted on one during a situation like that must be incredible. So, Steve’s body of work is astonishing. Now that Sunny is a part of Kronos, I think it’s time to call Steve again.

Tell me how you first connected with the composer Aleksandra Vrebalov.

It was in 1995 that Aleksandra, then a student at the San Francisco Conservatory, was doing her masters degree. I hadn’t heard of her. She sent me a cassette and I listened to it. We had a cup of coffee, and we’ve been friends ever since, talking about life, music, and the universe. The trajectory and growth of her work is truly astonishing. There has been a lot of documentation of our work together. Once, we were doing a symposium for young composers in Fresno and I was asked to provide some background on a composer we’ve worked with for awhile. At that point, there were all these emails back and forth between Aleksandra and I about her piece “…hold me, neighbor, in this storm...” She had just finished it and there were hundreds of emails about it and things that influenced it. It was put together in book form for the symposium. This level of communication doesn’t happen with every composer.

The piece emerged as a result of a DVD called Ziveli! Medicine for the Heart by the documentarian Les Blank. It looks at the Serbian community in Chicago. I saw it and thought I needed to share it with Aleksandra. The next time I was in New York, we watched it together. She was hearing Serbian music she hadn’t heard since she was a little girl. She was singing along to wedding, birthday and funeral music in it. It was so alive in Chicago in a way that it isn’t even in Serbia now. It was at that point that I said to her “Can you write us a piece that would somehow musically explain what’s going on in Serbia? From my perspective, it’s so complex.” That’s how “…hold me, neighbor, in this storm…” began.

“...hold me, neighbor, in this storm...” was also inspired by Vrebalov experiencing the NATO bombing of Serbia first hand. Elaborate on that.

I had never encountered a composer who wrote as her city was being bombed before. Aleksandra was the very first person to write a piece for Kronos during an event like that. My instinct was she should do whatever she needs to do—whatever comes to mind in that setting. I felt like it was something we needed to know about. I wanted to see how a sensitive musician would respond to that kind of event.

Tell me how Vrebalov came to arrange Wagner’s “Prelude from Tristan and Isolde” for Kronos.

In 2011, we were on a three-week tour. I Skype or call home every night when we’re on the road. During that tour, my wife Regan told me she saw the movie Melancholia, directed by Lars von Trier, three times. We’ve been married 43 years and she has never gone to see a movie three times in three weeks. I said “As soon as I get home, let’s go see it.” So, we did and the music used in it is “Prelude from Tristan and Isolde.” I had heard it before, but never in the same way as I had during the movie. I became addicted to the piece afterwards and needed to hear every possible performance of it. I was listening to different versions of it on YouTube and going to Amoeba Records in San Francisco to find as many recordings of it as I could. Then I heard about a recording of it from 1943 by Bruno Walter conducting the New York Philharmonic during the height of World War II. Walter escaped the Nazis. It had everything I wanted from music in that performance. It was made during one of the darkest moments of human history. It represented the height of our enemy’s culture—Wagnerian music. It was being played in our largest cultural capital by a Jewish conductor. I had to hear it. The performance has a perfection of timing and Walter had a connection to Mahler who also connected to Wagner. I listened to this performance and felt its immense importance. I could hear the forgiveness that music can give us. It reached a level I’ve never encountered before. I then realized that Kronos had to play the piece. The first person that came to mind to arrange it was Aleksandra. She didn’t hesitate for a split second. She said “I’ve loved that piece since I was 16 years old. I wanted to write it myself.” I said “Now, you get your chance.” I knew she would put in the level of effort and commitment required to make it happen. Aleksandra just jumps in fully into everything she does. We recorded this version at Skywalker Sound in December 2013. I can’t wait for our audience to hear it.

You just finished working on a 40-minute piece about World War I, written by Vrebalov, called “Beyond Zero: 1914-1918.” Give me some insight into it.

Aleksandra grew up in the culture where the first shots were fired in that war. She said to me “People in that part of the world are still fighting wars that happened 900 years ago. They don’t forget anything.” It seemed to me Aleksandra would have an understanding about that period from a vantage point that we wouldn’t have. She grew up with it in the soil. An interesting element the piece explores is the fact that so many musicians bought into the war. My favorite violinist, Fritz Kreisler, wrote a book about being a soldier on the Russian front. I was shocked at what I read. Ravel even wanted to fight at the front. He did everything he could to be assigned. When he wouldn’t be taken as a soldier, he wanted to be an airman. The piece also has a film component. Aleksandra and Bill Morrison have been to the National Archives and gained access to amazing World War I footage the Archives were getting ready to throw out. Bill has also been in Europe and elsewhere researching film footage.

Osvaldo Golijov is another major composer presence for Kronos. Describe his importance to the group.

I first heard about Osvaldo in 1992. We were playing at the Tanglewood Festival. I was looking through the program of composers. I’m always interested in reading what composers write about their work. Osvaldo was talking about a piece of his played at the festival called “Yiddishbbuk.” I was fascinated by what he said. He quoted three aphorisms of Kafka. As far as I knew, I had read all of the aphorisms of Kafka. But I had never read the ones Osvaldo quoted. So, I got his number and called him up. One of the first things I said to him was “Osvaldo, I was reading your notes about ‘Yiddishbbuk’ and you quote Kafka.” There was a silence on the phone. Then he said “Well, actually, I made those up.” [laughs] He had invented some aphorisms that were close enough to Kafka that most people thought they were real. What Osvaldo didn’t know is that during my early twenties, I had read everything by Kafka that had been translated into English, including all the biographies. So, that’s where my relationship with Osvaldo began.

I remember our first rehearsal. It was in a hotel room and one of the things he said to me was “It should sound like you’re angry at God.” No composer had ever said anything like that to us. I remember Kevin Volans saying “Think about the way an elephant walks and you’ll find the right rhythm for parts of ‘White Man Sleeps.’” Kevin also said “Think about the gait of a giraffe.” He used animals to describe what he wanted. Other people have talked about creating large spaces. There have been all sorts of ways of describing things. But no-one had ever said anything quite like Osvaldo. I’ve felt very close to him since our first conversation. I love rehearsing with him. He has an incredibly insightful way of thinking about music and describing it.

The first piece he wrote for us, “K'Vakarat,” from Night Prayers in 1994, featured Mikhail Alexandrovich, a Latvian cantor. It was an incredible prayer. Shortly after that album came out, we were playing in Lisbon and heard the music of Carlos Paredes, the great Portuguese guitarist. It seemed to me that Osvaldo should know about this music and perhaps do some arrangements for us. He said yes and the first one he did was “Cancao Verdes Anos,” a very beautiful song on the Caravan album. Osvaldo is also responsible for us working with Taraf de Haïdouks, the great Romanian group. The only person who could possibly imagine bringing us and them together was him. We met with them in London in 1998, during those days you could still smoke wherever you wanted to. The room was blue with smoke, and the group was excited about what we could put together. It all came together in a couple of days and we performed with them at the Royal Festival Hall.

At the same time, I was beginning to formulate the Nuevo album. I remember going to Osvaldo’s room where he was cooking dinner. We talked about things and I described what I was envisioning. Our conversation about it became the genesis of the album. Nuevo wouldn’t have happened without Osvaldo. There’s no question about it. Since then, Osvaldo has written a few things for us.

Explain the impetus for the Under 30 Project and the results it has yielded.

The impetus was really simple. Kronos was turning 30 in 2003 and we were trying to figure out what we should do. A birthday cake didn’t quite do it. [laughs] The question was “How can we mark this moment in a meaningful way?” We thought “Let’s commission composers whose lifespans are within the history of the group.” We’ve had five calls for scores and five fantastic new pieces emerge: "Oculus Pro Oculo Totum Orbem Terrae Caecat" by Alexandra du Bois; "CampoSanto" by Felipe Pérez Santiago; "Love Bleeds Radiant" by Dan Visconti; "Widows and Lovers" by Aviya Kopelman; and “Bombs of Beirut” by Mary Kouyoumdjian.

The Under 30 Project has been a great thing. As a matter of fact, I first got to know Derek Charke, who wrote a piece for Kronos and Tanya Tagaq, through the Under 30 commission. I remember calling Derek and saying “Technically, your birthday is two days before the deadline. There’s no question you’re under 30, but in your career, you’re over 30. So, let’s start our work independently of the Under 30 commission." It seemed to me he had it all together in a different way than a lot of the other composers. That was during the very first collaboration we had with Tanya. We invited Derek to basically sit in on our work with Tanya. He and his wife listened to the process. The reason I thought that would be a good idea is because the first music I heard of Derek’s was a transcription of Inuit throat songs. I think I must have heard some of those transcriptions for string quartet, which are probably the same ones Tanya heard on cassettes when she learned how to do throat singing. Tanya’s story is astonishing. She’s an incredible musician. It’s like she has a string quartet in her throat. She taught herself to sound like two people. When she heard the cassettes, she didn’t know it was two people performing. She thought it was a single vocalist and so she sought to replicate that herself. The story she tells is she learned how to do it in the shower after listening to these tapes her mom was sending her. So, Derek was there and one thing led to another. Eventually, it seemed like the right thing for him to write for Kronos and Tanya. The reason I mention this is to say the Under 30 commissions have yielded other relationships beyond those that have been the formal recipients.

The 2013 Under 30 composer was Mary Kouyoumdjian. What attracted you to her work?

Hank, John and I listened to 397 Under 30 CD submissions from composers across 50 countries in 2013. Mary Kouyoumdjian’s a vibrant person and the way her musical interests and family history intersect is really rich and fascinating. She’s an exceptionally interesting young composer. The way Mary brings in the past, present and future together with elements of her Armenian heritage is wonderful. Her music also reflects the fact that her parents lived in Lebanon. Mary is originally from the San Francisco Bay Area and now lives in New York City. There’s a certain resonance that I find deeply attractive.

Mary has written an evocative piece for Kronos with “Bombs of Beirut.” Mary is a first-generation Armenian-American whose family was directly affected by the Lebanese Civil War and Armenian Genocide. She was inspired to create a work that would reflect day-to-day life during wartime in Beirut. The piece includes interviews with Mary’s family and friends about their experience in the war, together with recordings of ambient sounds taken from an apartment balcony during the war. Those recordings include the sounds of missiles hurtling through the air and bombs exploding nearby. It’s extremely moving for Kronos to play and listeners to hear.

Take me through the history of the cellists that have been part of Kronos.

When I started Kronos Quartet in September 1973, Walter Gray was our cellist. I remember being in my parents’ backyard with Walter, filling out the forms to become a not-for-profit organization. We were eventually registered in the state of Washington and that was a very important step in the group’s history, which Walter was largely responsible for. During the five years he was in Kronos, he was an incredibly charismatic, wonderful cellist with loads of energy and rhythm. To be exact, it was September 19, 1978 when Walter and his wife Ella, who by then had become the second violinist in Kronos, made the shocking decision that they needed to leave the group that day. All of a sudden, three days after my son was born, that happened. I don’t know why they felt they had to leave that very day, but it had something to do with saving their marriage and family. So, Hank and I became a duo. Kronos was about to assume its status as artists-in-residence at Mills College in Oakland, California. Hank and I divided tasks for the first couple of days after that. He was on the phone trying to find cellists and violinists. My task was to contact Margaret Lyon, the chair of the music department at Mills, and explain what was going on. Margaret was one of the greatest people I’ve ever met in my life. She singlehandedly saved Kronos because of what she said to me, which was ”Oh David, don’t worry. I know you’ll solve this problem.” [laughs]

Margaret is the woman that brought Darius Milhaud, the Budapest String Quartet, Luciano Berio, Terry Riley, Pandit Pran Nath, and so many other incredible people to Mills College. Now, Kronos was a duo a month before we were supposed to play our first concert there. I’ve valued her advice ever since. It gave us a feeling that we could figure this out and it gave us the room to do it.

Elaborate on what made Jeanrenaud an ideal presence for Kronos.

From this vantage point, it’s easy to think that everything happened all at once, but it didn’t. Everything that Kronos has done has been by tiny, little steps and lots of experimenting. At one point, it became clear that wearing normal concert attire that we’d grown up with didn’t fit the music we were playing or the concerts we wanted to do. So, we started trying something else. At another point, we were doing theater pieces and we thought “Okay, what does that mean for the members of a string quartet?” And that began the emergence of the theatrical element of our performances. I think Joan was very instrumental in setting various stages for the group. I can’t recall someone with as much gritty willpower as her. I remember a concert she played, after which it was determined that she had appendicitis and that her appendix was huge and ready to explode. She got to the doctor just in time to have it operated on. I’ll never know how she played the whole concert. I’ve also seen her surmount physical problems that would pretty much stop almost anyone else. How she’s dealing with multiple sclerosis right now is incredible. She has always been a big inspiration for us. All of the composers we’ve worked with during her time with the group always had a special musical connection with her, given her rare combination of rhythm, incredible melodic sense, timing, and stature as a performer. She’s the cellist that has been in Kronos the longest and her importance and influence remain to this day.

How did the transition to your next cellist, Jennifer Culp, occur?

Joan told us quite early on about her multiple sclerosis diagnosis. We took a sabbatical of a few months. When it became known that Joan was going to leave the group, I didn’t have any question that it would continue. But as people found out, the question of whether or not it would continue was out there, because Joan had become so identified with the group. “What would it be like without her?” was asked by many people during that period. What we did was engage in an audition process and tried a number of different cellists. The one that came to the top of the list was Jennifer Culp. At that point, Jennifer was living a few blocks away from our rehearsal space in San Francisco. Very quickly, we had Jennifer, who’s a great melodic player. You can hear her sound on our recording of Alan Berg’s “Lyric Suite.” She gets an amazing tone from her instrument. I think her experience of playing in groups and her sense of sound made her the right choice then. However, the intensity of the touring schedule was insurmountable, which contributed to her departure.

Jeffrey Zeigler then replaced Culp. Tell me about that change.

After Jennifer left in 2005, Jeff was going to be a substitute for the summer. Things just clicked and it was excellent. He stepped right onto a moving train, didn’t lose his balance and did all these incredible performances. He had an amazing rhythmic sense and just held down the bass end. We shared so many wonderful experiences, from the Awakening program, to “A Chinese Home,” to the renewal of “Black Angels,” to the Floodplain, Henryk Górecki and Vladimir Martynov albums. We made many recordings and did a lot of large-scale pieces together and Jeff was always a willing partner in these adventures.

As time went on, Jeff became a dad and it became clear his family needed to live in New York. We’re a San Francisco-based group and our members need to be here. Jeff announced on October 1, 2012 that he needed to find a way of transitioning out of Kronos. We looked at our schedule and realized the 40th anniversary of the group was coming up. The question was “Should we bring someone new into these obligations?” and the answer was yes. We chose to move forward with an extensive audition process and thought about all the qualities that were needed for a new cellist.

Describe the audition process that led to Sunny Yang joining the group.

Let’s put it this way: I wouldn’t have survived an audition for this group. [laughs] It takes someone with a really broad interest in music and a great deal of focus and energy. I wanted a person who could take Hank, John and myself to another level of creativity. I think of our work in chapters and this feels like a new chapter that requires a great deal of energy. We wanted someone who could lift us all higher. I feel we found that person in Sunny Yang.

We kept the audition process a private thing. We didn’t want to announce it. It was personal for us and we didn’t want to get called by every cellist in the universe. Just like Margaret Lyon told me back in the early days, we knew we could solve this problem and we wanted to do it ourselves. John, Hank and I spent a lot of time checking out hundreds of cellists on the Internet. I’d also go to Amoeba Records and listen to every cello record I could find. At a certain point, we all became pretty conversant in the world of cellists. The field of young people playing cello is big. It’s incredible how this instrument has attracted so many amazing musicians.

We then had a number of candidates and at a certain point, I got a call from Judy Sherman, our longtime producer. She’s the one that gave me Jeff’s number eight years before. Well, she gave me another number eight years after that and it was for Sunny Yang, who lived in Los Angeles at that time. She was born in Korea, and her family moved to South Africa when she was 11. At age 16, Sunny went to Interlochen Arts Academy in Michigan. After that, she studied in England and then moved to Los Angeles.

So, I called her and she became one of the six cellists that we considered. We came up with a vast selection of music that would really give us an idea of their stamina, chops, and rhythmic and melodic senses—all the things one needs to play the music we play. Each audition was a two-part process. The first part was more acoustic and the second part was with our sound engineer, with headphones, mics, backing tracks, and auxiliary instruments. In fact, Sunny learned how to play the Omnichord off YouTube, as the other cellists did, probably. We needed to know about the cellists’ sense of adventure. In the end, we felt the person that clearly elevated us the most was Sunny.

Sunny is fearless. She also has a sense of the bow that is incredibly special. When Sunny first sat down and started to play with us, I could not believe the way she used the bow. It was absolutely spectacular. Suddenly, I was finding new things I needed in my own bowing. This is what I mean by how one person can affect everyone else. I’ve noticed that when we change members in Kronos, we’re not just changing the person and instrumentalist. What happens is each of our roles in the group becomes different, including the dynamic, the vibe of rehearsals, and the vibe between us and composers.

You reunited with Jeanrenaud for the Music of Vladimir Martynov album in 2011, as well as a few shows. What was it like to reconnect with her after such a long hiatus?

It was profoundly beautiful. Joan was a member of our board for many years after she left the quartet. Joan and Jeff Zeigler, our cellist during this period, were close. I remember thinking at a certain point after Jeff joined the group that there seemed to be a kind of natural feeling when the five of us were together. I started noticing that when Joan was at the board meetings.

The piece we recorded, “Schubert–Quintet (Unfinished)” by Vladimir Martynov, draws from Schubert’s “String Quintet in C Major.” One of my favorite artistic experiences in any form is “String Quintet in C Major.” I don’t know this for a fact, but I probably have one of the largest collections of recordings of that piece that there is. I think of that work as one of those rare moments in the art form in which everything comes together perfectly. It’s just amazing.

“Schubert-Quintet (Unfinished)” came about in an interesting way. There was a concert scheduled for the Yerba Buena Center in San Francisco on September 11, 2006. But Steve Jobs had an unveiling of something, so the concert got moved to the Herbst Theatre, which is where the United Nations Peace Charter was signed after World War II. I realized “Okay, September 11, 2006, Herbst Theatre, United Nations Peace Charter—we have to do something different for this concert. We can’t just show up and play whatever we’re going to play. This requires some thought.” So, I spent eight months figuring out what we could do that night. We were in Russia a few months before that playing Terry Riley’s “Sun Rings,” for which we need a large choir. The director of the Russian choir gave me a CD. What I needed was the ending for the program—the last piece. I wanted the most beautiful piece I had ever heard in my life. Basically, I wanted Beethoven’s “Cavatina,” but from our time. I was listening and listening, but not finding it. Then all of a sudden, in the hotel in Moscow after performing “Sun Rings,” I put on the CD and eventually one of the most beautiful pieces I had ever heard in my life emerged, which was “The Beatitudes” by Vladimir Martynov.

We had worked with Vladimir before. In fact, by that time, he had written “Der Abschied,” inspired by Mahler. So, I then asked him to create a new version of “The Beatitudes” based on the original choir version for Kronos, which was fantastic. “Der Abschied” was wild and amazing too. It just seemed like Vladimir was the kind of composer who could become Mahler, as much as one person can become another person. I was then thinking about Jeff, Joan, Hank, John, and myself. I thought Vladimir should write a piece for Joan and Kronos. I asked him if he could imagine writing a quintet. I told him the whole story about Joan's years in Kronos. When we first played in Moscow, Vladimir attended. He knew our recordings with her and had been influenced by that music and those albums. He immediately said yes. He eventually wrote six or seven versions of “Schubert-Quintet (Unfinished)” before he sent the final one to us. I feel the recording of the second movement of that piece is Kronos’ best recording to date in terms of sound. I even played it at my mom’s memorial because I wanted the best for her. It’s the best I’ve heard of my own playing too. Vladimir definitely gave all of us something to express the inexpressible and it was a great honor and pleasure to play with Joan again.

Do you consider Hank Dutt, John Sherba and yourself to be a brotherhood?

I’ve been playing music and sharing so many things with Hank for 36 years and John for 35 years. I’m just glad they’ve put up with me for all of these years. [laughs] They are the inner voices of Kronos. When I look over at them from the corner of my eye and see the way they make music and relate to music, it’s with a great deal of affection. It’s a brotherhood, definitely, but it’s even more than that.

I was looking at Hank’s hands the other day and I thought “What is it about this guy? He’s able to get a sound out of the viola that is just awesome. No-one else gets that sound. I’ve never heard another viola player who sounds like that.” Hank joined the group in 1977 when we first came to San Francisco. By 1978, I had two little kids and the music library was lining the floor of our one-bedroom apartment, getting bigger and bigger by the day. In 1979, Hank said “I think the library ought to come over to my place.” Since then, Hank has been Kronos’ librarian. What he’s done to make our library organized and useful, and something other musicians can benefit from and access, is astonishing. We also used to call him “Hank the Bank” because he took care of all the money. [laughs]

When I look over at John, I think “He has so much love for the violin as a force in the universe.” John probably has the largest collection of violin records on the face of the earth. He knows every one of them. He is an authority on violinists. John is an amazing force in life and as a violinist. He’s a truly wonderful person and I’ve had a great time playing with him all of these years. A lot of times in quartets, violinists are at each other’s throats. That has never happened in Kronos. John also handles our audio and video archive. He’s responsible for keeping track of our hundreds of concert recordings and videos. John is the Rock of Gibraltar in a world of shifting sands.

Describe your philosophy as a bandleader in Kronos.

I’ve been given a great deal of latitude to explore over the years. I think everyone in the group knows I’ve been pretty much doing this since I was 12—not just playing quartets, but searching the world of music for experiences that might be meaningful to me, personally, and hopefully, to them. Along with that freedom, I feel a great deal of responsibility to each member of the group. Kronos is a way of life. I want our work to give each of us, and our friends and families, strength and energy.

It’s when there’s a new member in the group that one notices the role of bandleader. One of the things I wanted to be sure of when Sunny Yang joined Kronos was that she could lead the group—not even as a cellist, but as a person. That’s one of the things I asked her to do during the audition—give the opening cue to Bryce Dessner’s piece “Aheym.” I normally give this one. In fact, I’ve done this at every concert. For the audition, Sunny gave the cue and it was a really good cue that enabled us to play exactly together with her. Then I said “Imagine you’re Leonard Bernstein doing it.” And that was an awesome cue. [laughs] To me, cueing is a really important part of playing quartets. By cueing, I don’t just mean giving a sense of the pulse and timing, but giving a sense of the meaning of the music and drawing that out of each other. That’s something she does absolutely beautifully. For me, there’s a whole science of cueing and I think about it all the time. In fact, I’m doing a lot of mentoring these days with younger players and composers. I always advise them to go to YouTube and check out the conductors. I say “Watch Leonard Bernstein conducting a violin section. Watch what his arms look like. You can hear the sound coming out of his arms. You need to be able to do that.” There’s a science to this. There’s also a lifetime of study to try and make our bodies communicate the sounds we hear inside ourselves.

I can say one or two words to Sunny—just give her an image, for instance—and she totally changes the way she plays. It’s the same with Hank and John. We’ve developed a vocabulary and rehearsals become places where you learn new words and add to it. As we begin our fifth decade, I’m coming up with new definitions of what a rehearsal is. I think it’s a place where we learn together and teach each other. The success of our interpretations depends on how we communicate with each other and teach each other.

As for what I do as a bandleader, it’s that I try to be sure that communication is happening and step out of the way as often as possible. I’m not interested in the old European model of what a string quartet is, in which the group is named after the first violinist, and where the first violinist is bowed to by the other players before sitting down to rehearse. I can’t even imagine that kind of thing. I remember, in the earlier days, we’d be doing radio recordings in Austria or Germany, where they would have tonemeisters who would always want to put a special mic on the first violin to make it louder. That’s not how I hear the balance of the string quartet at all. I’d much rather hear the inner voices and lots of cello.

All four of you engage in theatrical elements, including interacting with props, devices, and toy instruments. Talk about the evolution of that element in Kronos’ performances across its career.

We’ve become more confident and exploratory over the years. In the early ‘80s, we did something called “Live Video,” which was the first time we had multiple costume changes, and sets flying in and out. We created an experience that was unlike any other concert we had done. At Mills College, we once had a concert with a singing robot that came onstage and joined us for some James Brown tunes. His name was Elvik. [laughs] “Black Angels” is an example of a piece with a lot of theatrical elements, too. The piece has involved staging since 1989. We’ve refined it many times since then and really improved it. Eventually, there was Tan Dun’s “Ghost Opera,” which we did with Wu Man, and more recently, Terry Riley's "The Cusp of Magic," also with Wu Man. That one was the result of being a grandfather. All of the toys onstage are ones I collected from all over the world to share sound with my granddaughter. We also did another theatrical piece called “A Chinese Home” with Wu Man and "Uniko" with the Finnish composer Kimmo Pohjonen.

Vân-Ánh Võ saw "A Chinese Home," as well as “Ghost Opera" and “Awakening,” in which there were stage sets and we were interacting with all kinds of things. There was a kids choir onstage, too. Vân-Ánh thought there were many avenues we could explore for our collaborative piece as well, so “All Clear” also had a theatrical element to it. We’ve been lucky to work with so many creative people like Vân-Ánh who have brought new elements into our work. Nicole Lizée’s work meant I got to play a “Thingamagoop.” It’s fantastic fun to play that instrument. John plays the turntable, Hank plays the Omnichord, and Sunny plays the Omnichord and Stylophone on her piece, too. In another piece we’re working on, we use a cassette deck, typewriter and the electronic game Simon. In a way, doing things like this isn’t unrelated to playing Haydn, because each part has a character and you become that character.

Reflect on your time working with Asha Bhosle on theYou’ve Stolen My Heart project.

As long as I live, I’ll never forget two moments with Asha directly related to the audience. One was at Carnegie Hall. There was a certain window backstage that let me look at the audience that was coming into the concert hall. I had never seen a Kronos audience like that in my life. Same with the Sydney Opera House performance. The dressing rooms allow you to see the beautiful harbor, but also the audience. I remember all of these wonderful saris and dignified, beautiful people coming in. I just loved it.

Thinking back on that collaboration, I realize I made a big mistake. I recently remembered how I first heard Asha and what I should have included in the liner notes of the album. It goes back to what I was saying about community. One of my closest friends, David Huntley, died in 1994. He introduced me to Henryk Górecki. David and I shared so many musical adventures. I still love him. After he died, his friends went through his CDs and gave out part of his collection to his other friends. I ended up with one of David’s CDs and it was called something like The Golden Age of Indian Film Soundtracks. On that CD was “Aaj Ki Raat” or “Tonight is the Night.” We did a version of that with Zakir Hussain on the Caravan album and I should have credited David. I love that piece. I had never heard of R.D. Burman, the prolific composer who was married to Asha, until then. So, I started to explore his work. Eventually, I found out how to reach Asha. She has a relative who lives in San Rafael and she visits our area quite often. Also, a close friend of mine, the music journalist Ken Hunt, knew Asha and put me in touch with her and her family, and we sent her our recording of “Aaj Ki Raat.”

I began to collect as much Burman as I possibly could. There's a lot to collect. I listened to over 1,000 songs of his and there are even more than that. From there, I chose the ones that are on the album. Asha said “Whatever you want, we’ll do it.” She was incredible. I’ll never forget when she and her son came to meet me shortly before the recording. Asha is a beautiful woman and she had this amazing sari on. She walked up the steps and I led her here in this room you and I are sitting in right now. We talked about the lyrics and their meaning. I wanted to get more information about Burman himself, so she sat here and told stories for hours. It was great. I was aware the queen of Bollywood singers was right here in the room. There she is, so regal, yet she’s also incredibly fun, modest and a real person. At one point, I looked down. I hadn’t looked at her shoes yet. I realized she was wearing tennis shoes. I thought “I love this woman! She’s perfect!” [laughs] So, we had a great time and recorded the album. The first session was recorded in a hotel room in Austria. We did a lot of the Kronos part of the recording right here in this studio where we're sitting.

What I wanted was for Kronos to become R.D. Burman’s orchestra and do whatever we had to do instrumentally to make it happen. We used all kinds of different instruments to recreate the sounds. We added one layer at a time. At a certain point, Asha was here and she recorded her parts. I was with her for every take. In Mumbai, she’s used to having a violinist record lines along with her. It’s almost like a ghost voice. If you listen really carefully to You've Stolen My Heart, once in awhile you can hear me with her. It’s very, very removed, because I was totally off mic. I loved the whole experience with Asha, including the live shows we did together.

Provide some insight into the making of Landfall, Laurie Anderson’s evening-length work for Kronos.

I’ve wanted Laurie to write for Kronos for 25 years. We’ve talked about it for that long, but it didn’t happen until 2012. I think for the longest time, she didn’t feel ready. She didn’t hear it. Over the years, she kept coming to our concerts. We had all kinds of conversations and then I heard her album Homeland and thought “She’s doing it. ‘Flow’ is a piece we could play.” So, I called her and asked if it would be okay for us to arrange “Flow.” By that point, it was already in the works that she was going to be writing for us.

Laurie has stressed the influence of Hurricane Sandy in Landfall, but the piece started before that. In that sense, it might be similar to our Early Music album, because Kronos was working on that before my son died, and what happened is the whole thing changed afterwards. It became much more itself. I think that’s true of Laurie’s piece as well. She recorded all of the improvs and rehearsals we did together. She sifted through them and found moments. Laurie collects and collects until the last possible moment. She was collecting sounds and possibilities three days before the premiere. We still didn’t know the sequence of events or have certainty about the narrative until a few days before, during rehearsals. We’d still be trying this and trying that. Her process was right for this piece. The most important thing is always finding what’s right for the material and relationship, and it definitely worked for Landfall. I love the piece.

You performed “Yesterday” with Paul McCartney at the 2013 Outside Lands festival in San Francisco. What did that experience mean to you?

It was a high point for Kronos. The original recording of “Yesterday” is likely the most widely-heard use of the string quartet in history. Many listeners around the world first heard two violins, a viola and a cello when they first heard “Yesterday.” So, for Kronos to play this “early music” with its composer was like being involved with a primary source. What a thoughtful, generous musician Paul McCartney is. And what an incredible body of work he has. Imagine playing one of Schubert's songs with Schubert singing—that's what it felt like to me. If Kronos had been around in the ‘60s, maybe Kronos would have recorded it with him. The day before Outside Lands, we were using Edison cylinder recording technology in order to sound as though we had recorded 100 years ago—so listeners can dig us up like they had discovered a sonic Pompeii or Herculaneum. To travel to an earlier musical time has been an important part of our work.

It was also wonderful for my wife to be at the show, singing along. It musically connected our earliest days together. It was also a birthday present for my daughter Bonnie, who got to hear the songs performed live that she heard us play and sing at home when she was growing up. A totally circular experience.

Kronos has many recording projects on the go. Give me a snapshot of what you’re working on.