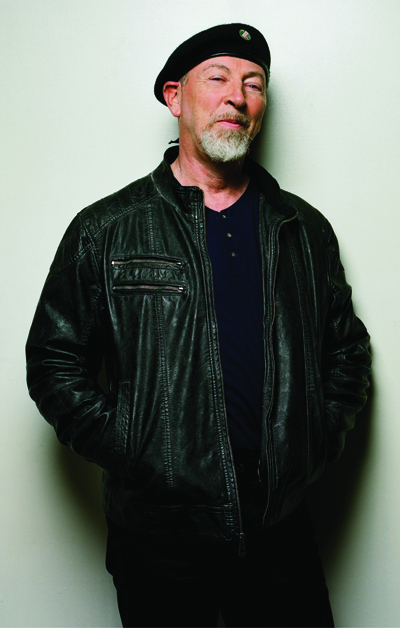

Richard Thompson

Thinking Visually

by Anil Prasad

Copyright © 2005 Anil Prasad.

As one of the world’s most celebrated and prolific singer-songwriters and guitarists, Richard Thompson knows a thing or two about crafting a good tune. His most recent CD The Old Kit Bag showcases a muse brimming with piercing wit, dark romanticism and evocative imagery. Thompson’s intricate, distinctive guitar playing remains the foundation his songs are built on, but it might surprise some to learn he often begins writing tunes without the instrument in his hands. He took a few moments off from recording his forthcoming solo acoustic album to discuss his creative process with Innerviews.

Why do you typically begin your songwriting process independent of physical interaction with the guitar?

It’s because I have a very visual approach to music. I visualize playing the guitar when I’m not playing it. I tend to visualize hand positions. Imagining playing the guitar is a slightly looser thing than playing it. You can hear more things sometimes. The fingers of your imagination aren’t quite as hidebound as your real fingers. Your real fingers fall into patterns a lot. The fingers of your imagination are less patterned, so in your mind, you can find new ideas easier.

How does that method intersect with lyric writing for you?

Songs can get written lyrics first, music first or all at the same time. Often, I think the best songs are the ones where it all comes together pretty much at the same time. During the initial imagination process, it's possible to just add the lyrics in as well. I think the mind is capable of taking that on in addition to playing the guitar. Sometimes it’s good to visualize yourself performing as well. That gives you a slightly different perspective when you’re writing. It’s all in the mind.

Sometimes you completely isolate yourself from the world and your family when you’re in songwriting mode.

That’s true. It’s nice to be able to isolate yourself completely in order to write stuff. I have a little room at home that’s hidden away where I can go and be alone. But over the years, I’ve had to train myself to work anywhere. When we had our last child, I was partly responsible for the childcare, so I had to figure out a way to keep writing when we were going through teething and things like that. So, I tried to train myself to write at any place, anytime if possible. Obviously, a little isolation and quiet is the best thing, but it’s a good idea to figure out a way to blast through whatever situation you’re in.

How has your songwriting evolved since your 1972 debut album Henry the Human Fly?

Hopefully, I've become better at the craft in that I understand the process a bit better. Hopefully, you remain inspired or manage to still get inspired at regular intervals. As you get older, your worldview changes. I don’t think it’s possible to write the same songs you wrote when you were 20. And when you’re 20, you can’t write the songs you’ll write at 50. Your experience changes you. You lose some of that youthful energy, but you replace it with a bit more perspective and philosophy. And hopefully, your skill level goes upwards.

I’m probably more efficient at the process now. I take more notes than I used to when I started. I have a notebook with me all the time. If I get ideas, I’ll make little jottings until I can get to an instrument or until I can get an hour to sit down and figure something out in more detail. I keep different working hours to be more productive. I used to get up at noon—which is a good musician time to get up—and started songwriting about midnight. By the time I was hitting the right flow, it was about four in the morning and then I fell asleep. So, I had a productive sort of half-an-hour. [laughs] These days, I wake up at 6:00 a.m. and start writing by about 7:00 a.m., so I have a lot more hours when I’m basically awake. As a result, I write more. It’s a more productive cycle. I do treat songwriting as a craft. You have to work at it. Sometimes, it’s a bit like an artist priming the canvas. It’s a mechanical process, but it can start your mind thinking on the creative side.

With the vast catalog of songs you’ve written, how do you avoid repeating yourself when writing new material?

I do think I repeat myself and it’s a struggle not to, but it’s a struggle you have to take on. Someone very wise once said "Copy everyone except yourself." Looking at other people’s ideas and twisting them to fit your own style is a good thing. You can also catch yourself traveling down the same road you’ve gone down before and nip it in the bud right then and there. You can say to yourself "I’ve done this before in 1937. I used the same chord sequence. How can I twist this slightly to make it into a different chord sequence? What’s a new melody that fits over these hackneyed, old chords? Can I use a different chord sequence and do something no-one’s ever done before?" It’s important to keep searching and not go for the obvious idea.

What yardstick do you use to measure if a song is worthy of public consumption?

You develop an instinct for your own best work. Once you’ve chosen a song because you think it’s good enough, you should go out and play it for an audience. They’ll let you know if it communicates. I think a song can be a good song, yet be too personal or obscure for an audience to get hold of. In those cases, you might think to yourself "This will be a song I sing to myself in the bath. It’s a very personal song. It means a lot to me, but it won’t mean much to anyone else." Alternately, you might say "I’ll abandon this song because it doesn’t communicate and I can’t see another use for it." Or you might say "I believe in this song. The world is 10 years behind me and doesn’t realize what a genius I am. I’ll keep singing it until people latch on." [laughs] Maybe you’re right. Maybe you’re wrong.

Is there a key to writing a song that works in both the solo acoustic and electric band arenas?

I’m not sure you can sit down and write with that in mind. That’s a tall order. I can’t, but I’m sure someone else can. I think you write a song because your creativity leads you to an interesting area and you then enjoy the process of writing and finishing a song. Perhaps during that process you think "Oh, this would be a good song for the band" or "This is a song that would be really good solo." Certainly, at the end of the writing process, you’ll know the answer, but you don’t have that knowledge at the beginning.

Recent times have seen you perform several 1,000 Years of Popular Music shows that find you covering a wide variety of material including opera, jazz, funk and country tunes. What string runs through the songs you’ve chosen for the show that makes them compelling and accessible in a modern context?

Let’s hope they are both of those things. [laughs] It has to be a song that we enjoy performing. It has to have some virtue that survives whatever time period it came from that can still be accessible enough to 21st Century listeners. Another big criterion is playability. If it can be adapted to acoustic guitar, a percussionist and three voices, or parts thereof, it stands a chance. Some things are just not playable. We usually can’t do it if it’s orchestral or needs too many voices or is just physically too hard to play. We do attempt things like a Gilbert and Sullivan song that would normally have a small pit orchestra accompanying it. Somehow it works if we play it with just acoustic guitar and percussion. It’s almost musical irony to attempt to play an orchestra arrangement with just these instruments. It works in a tongue-in-cheek way.

You sifted through a vast breadth and depth of material to put the shows together. Did that process give you any new perspectives on songwriting?

I think so. Speaking of stealing from everyone except yourself—that’s a lot of people to steal from. [laughs] Over the course of a thousand years, as history moves along and fashions change, many old fashions and ideas get thrown out. For instance, there are some terrific ideas from early jazz that got jettisoned very quickly. It’s nice to have a look at those things and I think they have influenced other things I do.

Do you see yourself as a keeper of the flame of any of these older traditions?

I don’t really want to be. I think there are people who are specialists in the fields who really do that. For instance, in early music, there are specialists who do nothing but play that stuff. I suppose they are the true keepers of the flame, although their interpretations are subject to the fashion of the time. The way 13th Century music is played is an interpretation. We don’t really know how they played that music. So, there’s a bit of guesswork involved. The majority of people who play early music are those who come from classical music, so they’re trained in a certain way. Sometimes, I think their interpretations are a little too stiff and not quite funky enough because they don’t really know how to be funky.

You occasionally delve into novelty song territory with tunes like “Dear Janet Jackson” and “I Agree With Pat Metheny.” What motivates you to spend time writing these pieces?

I think they write themselves. I get pissed off at something and lo and behold, it appears on the page, and then I actually have the nerve to sing them to an audience occasionally. A song like the Janet Jackson song has a short shelf life. It was topical for about three weeks. Then life moves on and it’s time for the next one.

Are those songs designed to balance out the darker, sardonic side represented by your more concrete output?

If I throw a song like that into a concert, it’s because it feels like that kind of energy is needed at the time. Perhaps there’s been too many slow songs or things have become a bit too dark. I’m happy to throw in something a bit lighter. A song like that is an opportunity to give the audience some variation. It also confuses the audience. If the audience thinks you’re a serious, slightly doomy kind of a writer, a song like that throws them slightly off balance, which I think is a good thing. All audiences should be slightly off balance.

Do you consider yourself a serious, doomy songwriter?

I don’t consider myself a doomy songwriter, but other people do. However, I do think I’m a serious songwriter. If you’re going to do justice to some topics, you have to dig a bit deeper and longer. As you get deeper, things can get more serious. For instance, to write a love song that does justice to the subject, you have to get pretty involved. And for me, it’s not always about happy endings.