Alam Khan

Modern Messenger

by Anil Prasad

Copyright © 2012 Anil Prasad.

Alam Khan has a foot in two worlds. He’s a masterful sarode player who’s furthering the legacy of his father Ali Akbar Khan through his own work in the Indian classical music world. Alam is also an avid underground hip-hop fan who has engaged the genre as a producer, beat maker and occasional rapper—and now, via sarode as well.

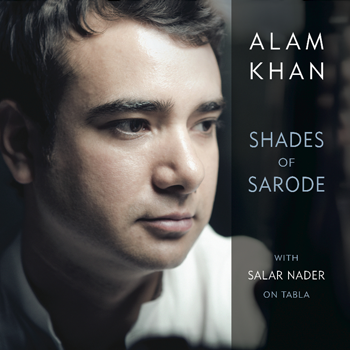

He just released his first album Shades of Sarode, a recording of diverse ragas that also features renowned tabla player Salar Nader. The recording offers pieces that range from four to 13 minutes and explore a wide variety of moods and dynamics. Khan intentionally chose shorter durations in order to generate opportunities for the music to be heard beyond traditional Indian classical music circles. While a raga can often exceed an hour in length, Alam, 29, felt his debut release should embrace a format with potential to create interest with younger listeners and the myriad ways they consume music in the mobile and online universes.

Alam also hopes to reach a new generation of listeners through collaborations with artists outside the Indian classical music spectrum. His sarode work appears on the best-selling Tedeschi Trucks Band blues-rock album Revelator. Alam is also working with San Francisco Bay Area hip-hop legends Eligh and Zion-I. In addition, he recently guested on tracks by the emerging Asian electronica act Gods Robots.

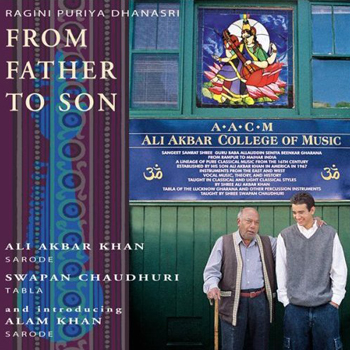

It goes without saying that Alam’s lineage is both impressive and intimidating. As the son of Ali Akbar Khan, he follows in enormously large footsteps. The elder Khan, who passed away in 2009, was a key figure in bringing Indian classical music to the West. He is widely acknowledged as one of the most important sarode virtuosos in history, and his recordings are considered among the most important pillars of his genre. In 1967, he established the Ali Akbar College of Music, based in San Rafael, California. The school is known as one of the world’s preeminent Indian classical music institutions and continues under the direction of Mary Khan, Ali Akbar Khan’s widow. Alam now serves as a teacher at the college.

Alam’s own journey of musical discovery is chronicled in the new documentary Play Like a Lion: The Legacy of Maestro Ali Akbar Khan. The film captures Alam on his first solo tour of India without his then-ailing father. It’s a moving piece of work that explores his complex emotions about continuing his musical and teaching explorations after the loss of his father. Alam emerges at the end embracing the challenge of moving forward, determined to ensure the sarode and Indian classical music thrive in the decades ahead.

You waited a long time to release an album under your own name. What made this the right time to do it?

After my dad passed away, I started teaching and also decided I want to go full throttle as a performer. But I was always notorious for being the guy that didn’t have an album. All the Indian classical musicians and listeners would say “Where’s your album?” My mother was always really encouraging me to do one as well. Even though I didn’t have an album out until now, I was one of the first people on YouTube performing Indian classical music. I played in a video for a group called Listen for Life. It’s an interactive website for kids that focuses on different music and instruments from across the world. They wanted to use a clip of me on YouTube. So, when you typed in “sarode” into the YouTube search engine, my clip was the first thing that came up. This was years before Indian classical music got really popular on the Internet. There was a time on YouTube when there wasn’t much of it at all, and now it’s everywhere. So, I was right at the beginning of it and that clip received more than 200,000 views.

Going back to the CD, I decided to bite the bullet and release one. I’m a perfectionist and never really happy with my playing, which is why I waited. I would say I’ve played a total of two concerts that I felt were good enough to want to listen to. However, the recordings of those shows didn’t come out well enough to release. Ultimately, I decided to record an album here at the Ali Akbar College of Music that would be more accessible for Western audiences. I took a similar approach to my father’s old recordings in which he would do several pieces between 15-20 minutes long. I did that so the music would work for radio, iTunes, and similar things. Of course, there’s the crowd that knows Indian classical music that expects it to be just one or two tracks, but I wanted something with shorter pieces. I’ll have the rest of my life to do longer format stuff. It’s not like I didn’t play classical music on it. I did, but I took a certain approach to playing that was more upbeat and aggressive in a way. I really want people to hear the sarode. I’m a purist when it comes to classical music, but I want to also reach people who don’t listen to Indian classical music, which is why I chose to present the music this way.

How would you describe the audience you’re going for?

My dad was the face of our school. He was an active performer in the world. People could always see him perform and knew it was a possibility to learn the music directly from him at the school, not just through one of his students. People were able to experience him teaching this life-transforming music himself. Now, with him no longer around, there really isn’t a face for the school. We have Swapanji [Swapan Chaudhuri] teaching tabla, but the sarode needs to be reintroduced. By that, I mean it has to keep being reintroduced to younger generations. It’s important that we reach them as an audience with this music. We’re getting further and further away from the ‘60s. So, I feel the more I perform and the greater presence I have in the music world will help contribute to keeping the school alive and well. People need to understand that we’re still teaching my father’s music and that you can learn it. I also want as many people as possible to listen to this music. So, I’m seeking to perform more and collaborate more, including getting the sarode into different genres of music. I also want to be able to stand behind anything I release. There’s a lot of fusion music out there and most of it is not very good. So, I wanted this album to be about good music, period, and be accessible to a lot of people.

Describe the choice of ragas on the album.

There wasn’t a lot of thought involved in it. I didn’t want to go into a studio and have restrictions about what got recorded. I met up with one of my father’s students who’s a recording engineer that did a lot of work in the past for him. We set up in the tabla room at the school and started recording. Salar Nader came into town and we played from morning until evening. The vibe was that these are going to be 10-15 minute sections of pieces. We played whatever was in my mind at that time. That’s what we always do, really. My father always said “If you feel like playing a certain raga, you should play it. Don’t play one because someone wants you to play it. If it doesn’t feel right, don’t do it, because the raga won’t show its face to you.”

Your mother Mary Khan co-produced the album. Tell me about her role.

She runs Alam Madina Music Productions, the label that’s released all my dad’s recordings in America. She started it. Part of her role is to listen to the recordings and help determine what’s releasable. She’s also very active in the studio and in the mixing process. For instance, we just released my dad’s Rag Darbari Kanada: The 80-Minute Raga CD. It’s a reissue of the original Connoisseur Society 2-LP set from 1969. She actually changed the sound of it. On the original recordings, tabla was on the left and sarode was on the right. So, she did some EQ and panning stuff to bring them together. My mom is the one that runs everything with the record label and the school too. She’s the director. Anything my mom has to say is something I take to heart beyond anyone else.

Describe why you chose Salar Nader to accompany you on tabla for the album.

Salar is a friend of mine and we’ve known each other and played together for years. We get along well. He’s young and I can talk to him as a friend. If I chose one of the more senior tabla players, who I’d love to work with in the future, I probably would have been more nervous. With Salar, I can say “Man, that sucked. Let’s do it again.” [laughs] It’s relaxed. It’s chill. He’s very respectful of the music and my family, and I can talk to him as a buddy. He also lives in LA, so he’s close by. We just vibe well together.

What evolution do you see from your work on 2002’s From Father to Son album with your dad to your new recording?

A lot. When I listen to From Father to Son, I hear a certain period of my playing. I wasn’t putting myself out there as much, musically speaking, as my father wanted. I wish I could play with my father now, especially when he was in his 60s and 70s during the 1980s. Those recordings of him with Swapanji and Zakir Hussain during that period are just killer. I also remember all of those amazing concerts he did. So, I wish I could have played with him back then and taken chances and more risks. But I wasn’t ready and life didn’t work out that way. Now, I’m here alone and have to figure things out. I’ve practiced so much since then and realized so many things. It’s something that happens the longer you do this. You go uphill and then as you’re going uphill some more, you switch gears and you drop down and start again. You’ll start going up again and just when you’re feeling good and things are making sense, you start playing everything out of tune and the ragas don’t make any sense. It’s like “What the heck happened? Yesterday I felt like I was finally getting somewhere.” Well, you did get somewhere, but you reset. Now, you’re onto the next thing. I’ve felt like a beginner over and over again since then. But it’s more about beginning another phase of my playing each time.

Your father said similar things right into his 60s.

That’s true. He said something like “I was 50 before I even enjoyed playing,” which is ridiculous because the music he played was so beautiful. But you can’t really understand how the minds of people like him worked. He was the master.

In between those two albums, you put out a hip-hop disc called Raps, Rupees, Rickshaws.

I did, unofficially. That was not an Alam Khan album, but something separate that was done for fun back in 2003. The group we had was called Random Heads, and an earlier group I was in during high school was known as Prolifics. I just loved playing music. I didn’t have a band and a friend showed me how to make beats. I thought “Oh, I can do all this stuff on my own. I don’t need a band.” That was awesome to me, because at the time I was listening to a lot of Bay Area hip-hop. I grew up on Seattle grunge music like Nirvana, Pearl Jam, Soundgarden, Alice in Chains, and Smashing Pumpkins. Later on, I got into bands like Tool. I also listened to Beethoven, Mozart and my dad’s recordings. Once the Seattle grunge thing died out, I found the same kind of raw energy in underground hip-hop. I also listened to a lot of bad music for awhile. My first hip-hop album was Young MC’s Stone Cold Rhymin'. It’s funny, we’re archiving my dad’s recordings and I came across a random DAT in a box of his stuff. It was unlabeled and I assumed it was one of my dad’s performances. I played it and all of a sudden Young MC’s “Bust a Move” comes on, and I thought “Whoa, how did that get in there?” [laughs]

You seem way too young to have been listening to something as old school as Young MC.

I’m 29, but I was listening to Young MC in third grade. I had that album, Dr. Dre and other stuff at the time. I also took an interest in gangsta rap because I liked the beats. I didn’t like what they were talking about, but I liked the production and the sinister-sound beats, as well as the melodies that focus on minor notes and changes. Next, I found the underground hip-hop scene and it was something I could really relate too. It was about life and philosophical stuff. Atmosphere, Rhymesayers, Living Legends, The Grouch, Eligh, Murs, and Zion-I are some of the things I listen to.

When I was doing hip-hop stuff, it was a way for me to write. I just wanted to make beats with a few of my friends. They were rapping and I thought if they’re going to do that, I might as well do it too. So, I took a crack at it. The early stuff I did was horrible, but as it got to the end of that time period, I liked what I was talking about. The lyrics were like musical journals. That’s the purpose it served. It also allowed me to relate to my friends more. We did little shows back when we were 17-18 years old. It was good for me and it played its course. But now, I’m working with Zion-I, which is awesome.

What are you getting up to with Zion-I?

Amp Live from Zion-I is making a new mixtape that I play sarode on. It came out of an album Eligh and Amp Live recently released called Therapy at 3 that I play on as well. After that experience, Amp Live called me and said “Let’s do a mixtape.” I said “For sure.” The two singles coming out from that are just him playing beats and me playing sarode. I love hip-hop and for it to come together with my sarode playing in this way is really cool. I’m not making beats or rapping, which I used to do for fun. I’m actually playing my sarode and they are working that into what they’re doing. Amp Live isn’t just a hip-hop guy. He’s done a lot of remixes and listened to a lot of music.

How did you initially connect with these guys?

I pretty much attacked all the social media sites. I decided I was going to get on all of them and have a profile everywhere. In this day and age, everyone is doing everything themselves. You have to be visible. One of the things I did was create a Twitter account. I thought “Twitter? What is this? I feel so stupid doing it.” But I did it and thought about people I could follow. I wondered if Eligh had an account. I grew up listening to him and love him as a rapper. I used to bring his albums with me when I was out on tour in India with my dad. I’d be traveling by train, listening to Eligh, Living Legends and Atmosphere. So, I decided to follow Eligh on Twitter. The next day, I was up late and posted a video of me and my brother Aashish playing a sarode duet in Delhi. And then I got a tweet from Eligh saying “Hey Alam, your instrument is beautiful. I’d love to get you on my new album if you’re interested.” I remember thinking “Who is this? Is this really Eligh? This has to be a joke.” Sure enough, it was him. He said “Here’s my email. If you want to do it, get in touch.” I think he thought I lived in India. [laughs] I tried to tone down my excitement because I’d been listening to his stuff forever. But I wrote him back and said “I love your albums.” And he said “Great, it helps that you already know my music.” It was super random. Well, that sold me on Twitter! [laughs]

What did your father make of your interest in hip-hop?

He used to make funny jokes about it in class when someone was playing or singing something wrong. He would say “It’s not like that hip-hop music” to the students and I would be mortified. [laughs] I gave him the first little CD I made through my mom, who played it for him, because I was too embarrassed to give it to him myself. Remember, this was just us printing out little labels and making home-made CDs. These were not official in any way. I wasn’t trying to be a hip-hop artist. It was just for fun with my friends. When he heard it, he said “There is not enough melody and music. What is going on? Why are you guys talking so much?” [laughs] I remember thinking “Oh man, I cannot believe I gave him that stuff.”

I never really wanted to be a rapper. For a time I was excited, thinking I could ultimately become a producer and sell beats. I made beats for other people, including some of my friends who still do hip-hop. For instance, I used to record with Zion-I’s hype man D.U.S.T., who lived in the same town as me. We used to make music in a shed in the backyard of my house. I thought perhaps I could build up a clientele of people and work as a producer, but you really have to hustle this stuff and connect deeply into that world. This was going on during the latter part of my dad’s life. I ultimately decided “No, I need to play classical music.” It’s funny. I had an external hard drive with probably 100 beats that were really good. I said “If this hard drive fails, I’m going to stop.” And it fried. I lost all of those beats and said “That’s it.” And it was, to an extent. I still have a Pro Tools setup and made some beats here and there, but after that I really closed that chapter. This isn’t a side that comes up during interviews, because people see me as a classical musician, which I am. That’s really what I do. But there is this whole other side of my interests as well.

You a guest on a new electronica project called Gods Robots. Tell me about it.

I wrote to the producer Janaka Selekta, because I had met him previously, and knew Salar was doing stuff with him. It’s part of the effort to cross over, slowly. My goal is to make other music with my sarode, in addition to Indian classical stuff. So, Janaka said “Yeah, let’s do something.” We met up and made the track “Rain” and then his vocalist Shri laid down her tracks in Bombay. I recorded a couple of hours worth of parts and Janaka arranged them. He chopped up sections and did stuff with them. I also played some longer passages which he kept in their entirety. We then did something similar for the song “Falling.” I listened to a lot of his songs and picked the ones I felt I could relate to. I’m not just trying to play sarode on people’s stuff just to do it. I want to figure out what songs I vibe with and play on those. I’ve also been talking to Karsh Kale and Talvin Singh about doing some work together. I really want people to hear the sarode in as many contexts as possible.

Your first instrument was guitar. Describe how you transitioned from that instrument to sarode.

My mom used to play Jimi Hendrix stuff for me. She would also always be listening to Crosby Stills and Nash, Credence Clearwater Revival and Janis Joplin. She loved that music. My dad was obviously super-classical, but even he had a few pop albums from the ‘60s. I was an MTV-generation kid, but I would come home every day from school and have this whole other Indian classical thing at home. I didn’t initially really appreciate and understand it. I wasn’t ready for it at first. I think rock and rap were what got my musical circuits going.

I was listening to Kurt Cobain and Jimi Hendrix and decided I wanted to get an electric guitar. As a little kid, it’s awesome plugging the guitar in for the first time, turning on the amp, and playing with distortion. My mom bought me a guitar for Christmas one year. I would learn a couple of songs here and there. One of dad’s students, Jai Uttal, would teach me guitar privately. And then my dad would give him classes at school. Jai would teach me chords and other guitar stuff, as well as how to play Hendrix songs. I would play at talent shows or in the school band.

Eventually, I started listening to my dad’s albums in a new way as a teenager, after I had played guitar for awhile. Suddenly, I heard the same angst and moody stuff in Seattle grunge in my dad’s music. One of the first albums I heard in which I had that realization was his Signature Series Rag Chandranandan album. His music took on a whole new life for me. I heard all of these emotions and moods. It was haunting and never left me. That’s why I wanted to start playing sarode.

Was there an element of your dad going “What the hell? Why is he playing guitar?”

Whether he thought it or not, he was always supportive and very happy. He would come to my room and say “Bring your guitar.” He’d sit there hanging out or eating lunch and say “Play something.” I would and he would say “Good, good, good. You’re doing music.” He was never on my case or anything like that. When I got serious about sarode and went on tour with him, he got more strict and things changed a little bit as the level of teaching changed.

Did it ever strike you that your dad was a “rock star” himself—that he was the Jimi Hendrix of an instrument?

It was a statement that would be in my head all the time. People always said “Your dad is the greatest sarode player in the world! He’s the best!” It was cool and great, but I didn’t understand the music or what it really meant back then. I’m still constantly learning things about my dad and his life. My dad was such a huge figure in India and the world. I knew that my dad was “the man” and a king of music. But as a kid, you can only grasp that so much. He was gone a lot for touring. I missed him like crazy. A lot of times it would be for months. I remember spending winters with just my mom, brother and sister. I’d go to school and do my thing while dad was in India. I didn’t really understand it all until when I really started playing and touring. I played basketball and wanted to be on the high school team. I realized that I wouldn’t be able to play basketball and study music seriously. So, I didn’t go to a conventional high school. I went to an independent study high school. I’d get weeks or months worth of homework and do it at home or take it on the road when I traveled with my dad to Europe and India. I’d come home and turn it in. During my sophomore year, the teacher said I could study for the high school equivalency test. The teacher was supportive and said “We want you to succeed as a musician. That’s what you need to do, Alam.” Together with my parents’ support, that’s what I chose to do and I’ve been doing music ever since.

Provide some insight into your goals as a teacher at the Ali Akbar College of Music.

A main goal is to ensure the college is alive and strong. By playing concerts and having a presence, I can help people know the college is there. It has only been two years since my dad passed away. My mother would always say “There are people who give up and it’s over, and there are people who don’t.” That sounds like a normal thing to say, but it makes all the difference. It’s true, we may have frustrations about some guy who made a pop song that everyone hears and is set for life, because in contrast, classical musicians like my dad played so much and so hard to give the music a presence.

The world just doesn’t see Indian classical music the way it should. There should be a category for it. It shouldn’t be called just “world music.” My dad used to get Grammy nominations and my mom would write the Grammy organization trying to get an Indian classical music category. Even on iTunes, it’s still in the world music category. Indian classical music should be respected the same way Western classical music is, because of its depth and the number of years over which it has evolved. So, I want to bring more focus to Indian classical music.

I’ll feel especially good if I can bring attention to the sarode. Everybody knows the sitar. People always ask “Do you play the sitar?” And then I have to say “I play the brother to that and it’s called the sarode.” Then I have to start my whole spiel about what it is. It would be really cool if people knew what it was from the outset. The thing is, there aren’t many sarode players right now. At the classes I teach, it’s tons of sitar players. I can teach the music to sitar players, but I am a sarodist. I want to be able to pass on what I know sarode-wise as well. I’m not going to be my dad, but I think I have a certain role to play in the way of relating to people and doing what I can to get the instrument known—and in return, having people discover my dad’s music. Part of that process is getting younger students involved. But there isn’t a person that’s young and accessible that can serve as a face for the sarode.

Could you be that face?

I would like that. That’s what I’m working towards. I’m not saying I want to be famous. I don’t care about that. I would like to be able to earn enough money to live comfortably and be happy. I just want people to hear the sound of the sarode. If I’m only a gateway for people to discover my dad’s music, that’s great. I’d rather them listen to my father anyway because he was brilliant. There should be more people playing sarode. Having a face on the instrument that people can relate to will help. The fact that I was born in America and have the musical tastes that I do can also open the door to collaborations that do justice to the instrument and Indian music.

Tell me about something you learned from your father that you apply to your own classes at the college.

My father would relate the music from such a personal level. He’d use super-mundane things from everyday life as metaphors and analogies. When talking about phrasing, he might say something like “It should be like you saying ‘How are you doing?’ [quietly] not ‘How are you doing?!’” [very loudly] He might also say something like "I just taught you this line of the composition and it’s just one room in the house. It’s the section before you move up to the higher octave. But don’t go upstairs yet.” He would create this whole world you could relate to through everyday life and that’s something. I find myself going to places like that to relate to other people too. Things come out when I’m teaching all the time related to the experience of being with him as my father and accompanying him on tour as his assistant and performing music. Everything was a lesson.

You’ve said the college needs to adapt in order to survive. Elaborate on that.

We have a computer we use for online classes now. At first, we weren’t into that at all, because this music is supposed to be about the intimacy of being there with your teacher, and the transmission of energy, guidance and care. In the beginning, we were only doing it for students who have studied with us before. We felt we needed to know who everyone was. That washed away a bit. Now, we want to find out a little bit about the person that’s studying prior to giving them lessons. We always encourage people to attend in person. Online courses are no substitute for being here at the college. But they have helped to get more students, including getting people to take classes in person. So, now they can keep learning from anywhere in the world if they have a fast enough Internet connection. This is something new for the Indian classical world. I wonder what our ancestors would think about looking in this glowing box? [laughs] Apart from that, we’re using social media to promote the school. Otherwise, we’re pretty much the same. We teach my father’s lessons in the pure Indian classical way he did. We had to find a way to do it now that we don’t have the master teacher with us anymore. He was the college. Having a college after his death is something nobody wanted to think about. Now, it’s here and we’re moving forward and something’s helping us. Maybe he’s helping us. We just have to keep on going.

You’re in the latter phase of “The Maestro & Me” campaign, designed to fund an archive of your father’s music and teachings. How are things going with it?

We’re down to needing $75,000 of the $375,000 goal to finish the whole thing. We’re going to house 40 years of my father’s incredible body of work. People will be able to learn from Ali Akbar Khan through video and audio. I don’t think that’s been done before for one of the masters of Indian classical music. Before, when one of the masters was gone, he was gone, and you have to take whatever a disciple says to you as truth. But now, you’ll be able to go and study at the archive. We want to make it public and free to people. It’s not going to be on the Internet. It’ll be housed here in the Bay Area, physically. You’ll have to spend the time to study in person. This archive will outlive all of us. It will ensure my father’s music and teachings remain. A couple of days a week, I spend hours digitizing concerts and entering data. When it’s complete, we will have a full database in which you can type in a raga and access every concert, composition and teaching related to that raga. People will be able to listen to his lessons, as well as literally hundreds and hundreds of hours of recordings no-one has ever heard. They’re just amazing concerts. There’s never going to be a lack of music to listen to. People will be able to come in and put on headphones and listen to hours of stuff.

Some of our students are the main people working on this project. They quit their jobs to work on the archive full-time. We rely on grants to fund it, but it’s a constant challenge. It’s a battle and we really want to get it done. A few colleges have said “We’ll fund the whole thing, but we’re going to own it.” We said no. We’ve approached all kinds of people from India, but the sad thing is a lot of Indians just don’t care. People from India would probably want it in India, and the wealthy Indians around here in America aren’t interested. This is their culture. Ali Akbar Khan is a treasure of their country. But they just want Bollywood or they want their son or daughter to take three classes and then they say “When can he perform? When can I have a concert at my house?” More Indian people should take enjoyment and pride in stuff like this. The college is here, his music is here, and people should help. I don’t think you can get more Indian than this. I understand times are tough for people, but it’s not that much money to finish it at this point, and what it would do for people to keep his music alive is just so vital. Eventually, we will get what we need to finish. It’s just about getting the right people involved.

I hope I do a lot more for my father in the future. There was never an official biography. Some people tried to do one, but didn’t finish it. A lot of Indians, when they write about him, stop when he comes to America. For them, it’s “He belongs to India. After that, whatever.” Well, he spent more of his life in America than in India, so you can’t just say “And then he went to the West, end of story.” [laughs] It’s more “And then he went to America and shared the music with the world, which is what his father wanted him to do.” So, a full, complete picture of my father should be written at some point.

Why not make the archive available online?

These are jewels. Our concern is if we put it online and everyone starts sharing, downloading and bootlegging, that the archive will lose its value. Some people would access the material that way and start saying they’re a student of Ali Akbar Khan. There are already people doing that. There are even people learning from YouTube now. People will call us and we’ll ask them “Have you been studying previously?” and they’ll say “Yeah, I’ve been learning sitar from YouTube for a couple of years.” It’s actually something people do now. It’s so bizarre. Some guys will take one lesson and they’ll call themselves a disciple.

How have your grandfather Allauddin Khan’s music and teachings inspired you?

Whenever my father taught me, he would always say “This is from your grandfather.” So, I always took them together. Whatever my father passed on to me was from my grandfather. People would comment on my dad and praise him by calling him my grandfather’s messenger. So, it was always about my grandfather in that sense. I never got to meet him. He died 10 years before I was born. I’ve looked at his pictures and have been so inspired by him. I have so much respect, admiration and wonder. It’s intriguing in a way given I’ve never met him. So many people in history have made such major impacts and my grandfather is one of those people. I wish I could have spent time with him. I would always ask my dad “Do you think grandfather would be happy with me?” and he would say “Your grandfather is with you. He’s taking care of you.” So, my grandfather was there in heart and spirit through whatever came from my dad.

We have all of my grandfather’s books. They’re handwritten. There are volumes and volumes of endless compositions, ragas and talas he created. They’re either in Bengali or Hindi. For years, we were transcribing this stuff in English. My father never got to teach me anything from those books, because he wasn’t well. It was something we were going to do. It’s something I want to do with Aashish, but we haven’t done it yet. There is so much knowledge. There’s no lack of that stuff. It’s overwhelming. It’s like “Okay, I’ll start one of 50 books today.” I don’t know if it would even make much sense to me because I don’t really understand how things are presented. Notation by itself is very hard to learn from in Indian music. It’s cool that there are a bunch of notes on a page, but you can’t get the ornaments or the feel of what’s behind it. So, right now I’m just making my way through all of the recordings and lessons I’ve had from my dad and that’s enough for the moment, but we definitely have a lot of material from my grandfather as well to consider.

Describe your relationship with Aashish Khan.

He’s very supportive of me and always has been. I don’t play sarode duets with people. I accompanied my father and I also do it with Aashish. We both have different sounds. When people hear us together, they say they can hear the distinction in our playing. It’s apparent to them. He’s part of an older generation, so the family dynamic has always been different. We don’t get to see each other very much. He lives in Los Angeles, teaching at CalArts with Swapanji. Swapanji is the chairman of the World Music Department there, in addition to his role at our school here.

How does spirituality inform your life as a musician?

When I think about Indian music, I think about its devotional aspect. It’s supposed to tune you up, heal your body and be used as medicine. All of that’s true. But I don’t want people to think “I have to get this album to go do yoga and meditate.” I want people to respect this as classical music that should be performed in symphony halls. So, my take is “Don’t get too spiritual with it.” [laughs] Having said that, my father had a huge temple at our home with pictures of all the Hindu deities, Mecca, the Koran, Jesus, Mary, Buddha, and more. He believed in it all. He would also say “Music is our religion.” He would ask me to take him to a church so he could go inside and pay his respects. He had respect for something higher than ourselves. He felt you need blessings, help and support from your ancestors and spirits. He was always that kind of person. I don’t subscribe to any religion, but it has been instilled in me that there is a god or there are gods. There is a higher power. That idea is always there when I’m playing.