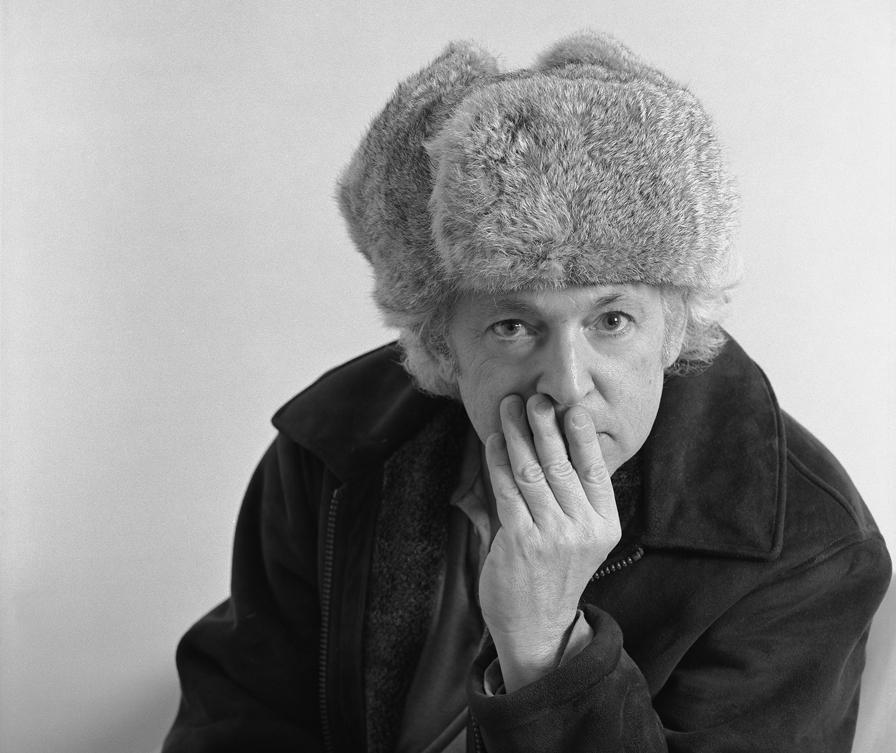

David Torn

Mercurial Mastery

by Anil Prasad

Copyright © 2009 Anil Prasad.

David Torn’s influence as a guitarist, composer and music technologist is epic. His expansive six-string prowess captures his emotional pulse in an extraordinarily unique way. With sounds ranging from the searing and soaring to liquid, loop-drenched atmospheres to full-on virtuoso shredding, there is very little the man can’t do with his instrument. He’s situated his guitar work across seven multi-genre solo albums that feature combinations of edgy, world music-infused jazz-rock, minimalist ambient explorations and cutting-edge electronica.

Torn’s fascination with next-generation guitar design, effects and digital workstations has also played a major role in shaping his aural aesthetics. In particular, his expertise in sampling and manipulating his own guitar output to create rhythmic and textural events that are then simultaneously merged into his real-time playing is in a league of its own. The technique has inspired and baffled countless musicians who have tried to reverse-engineer his approach.

Highlights of Torn’s recording career include 1987’s Cloud About Mercury, featuring drummer Bill Bruford, bassist Tony Levin and trumpeter Mark Isham. Its distinctive combination of improvisation, multiple time signatures and alternative scales with a melodic focus and percolating rhythms established Torn as a presence to be reckoned with. Subsequent discs, including 1995’s Tripping Over God and 1996’s What Means Solid, Traveller?, were equally ambitious, with their flowing, stream-of-consciousness approach that incorporated Eastern rhythms, ambient washes, stormy power chords, and surreal, buried vocals. He also deftly took on the realm of recombinant urban electronica with 2001’s Oah, released under the moniker Splattercell. Another high water mark is 2007’s Prezens. Created in collaboration with saxophonist Tim Berne, drummer Tom Rainey and keyboardist Craig Taborn, the album places Torn’s sample-and-morph tendencies within the context of a band capable of mirroring and extending his musical shapeshifting.

Torn has also created several widely-used sample discs containing ready-to-use loops and sounds. Innumerable film and television composers use his discs, and as a result, Torn’s work can be heard across myriad scores, often in an uncredited capacity. Thankfully, Torn’s dramatic contributions to this universe were eventually rewarded by his ascension in the ranks to a first-call soundtrack composer in his own right. He’s helmed scores for features including The Order, La Linea, The Wackness, and Lars and the Real Girl, as well as worked on the soundtracks of Traffic, The Chamber, The General’s Daughter, Three Kings, and Reversal of Fortune.

Several rock icons have also sought out Torn’s services as a guitarist, collaborator, producer, and consultant, including Tori Amos, Laurie Anderson, Jeff Beck, David Bowie, and Sting. And while the recognition is certainly welcome, he processes it through a perspective that ensures his feet remain firmly on the ground. That viewpoint evolved significantly post-1992, the year he was diagnosed with an acoustic neuroma, a life-threatening form of brain tumor. The surgery that followed was successful, but left him deaf in his right ear. However, his skills as a composer and player remained fully intact. In fact, his expertise as a mixer and mastering engineer have continued to grow since his recovery. Understandably, charting a positive path forward wasn’t easy for Torn, but the worldview that emerged is a model we can all draw inspiration from.

Tell me about your earliest creative revelation.

It was 1967 and I was 14 years old. It was the time of a remarkable flowering of the potential of the electric guitar. Jimi Hendrix was alive and playing, and I was lucky to have seen him a couple of times in concert. Jeff Beck was busy doing his thing too. A friend of mine had these little woods in Syossett, Long Island that we would go to on the weekend or at night and a bunch of us would go hang out in a little grass hut we had built. I was already in several bands playing creative music with a lot of improvisation because it seemed like it was okay to do in that era. It was de rigueur to play long trio improvisations in electric rock music back then.

We were sitting around the fire one night and everyone was talking except me. I was busy looking at the embers and thinking about the sound of music and why things sound the way they do. I would also hear guitarists play and their phrases—especially Hendrix and Beck—in my head as I sat there. It became a synesthetic effect in which a guitarist would play a phrase and I would think of it almost as a sentence with verbal meaning. If someone had asked me a philosophical question about the meaning of life, I might have been able to sing it back as a Hendrix phrase instead of saying something. That was part of my mindset at the time. It suddenly occurred to me the way the flames move is exactly how I wanted my guitar playing and music to sound. It was either an epiphany or a psychotic event. [laughs] But I never forgot about it. Maybe it was the only creative revelation I ever had because it was so formative. It meant a lot to me and it’s a feeling I’ve never lost.

At what point did you realize a typical guitar sound wasn’t for you?

It was in the very early days when I experienced rapid public validation that I was doing something that didn’t sound like other people, yet was appreciated. I was a young and very troubled kid and that actually led me to stop playing in public around age 16. I was also dismayed with the limitations of the club scene in which I played with people who were 10 years older than me. I dropped out of the scene and only played for myself from around age 16 to 20. I started playing live again after I engaged in a huge effort to fix myself by studying meditation techniques very seriously. It wasn’t until I went to a record store with my girlfriend’s brother at age 18 that I found and heard any music that even remotely touched me in a long time.

I picked up a record because of the way the album art looked. The cover made it obvious the artist was into the same kinds of meditation techniques I was into. It was Mahavishnu Orchestra’s Inner Mounting Flame, which had just been released. I took the record back to my girlfriend’s house and put it on and freaked out a bit at first. When I finally got into it, I was amazed. I didn’t think anything from the Indian subcontinent could be applied to electric music. I couldn’t figure out where this music came from. When I was a kid, my dad exposed me to quite a bit of North Indian music, but I had never heard those elements in this context. The cultural associations began making a lot of sense to me, and feeling inspired, I went out and organized jam sessions. The guys I was playing with would say “Let’s play this Hendrix or Cream tune.” I’d respond “No. Let’s just play and see what happens.” It was very exciting and it was the beginning of everything I do now.

Which musicians served as key influences as your career unfolded?

I rejected an initial interest in flamenco during my earliest years with the instrument in favor of a period focusing on Wes Montgomery, Shuggie Otis, Jimi Hendrix, Jeff Beck, and Mike Bloomfield. Then came the fascination with Mahavishnu Orchestra which led to Herbie Hancock and the Headhunters, and Miles Davis. The next period was the direct influence of John Abercrombie and Pat Martino, my two main teachers. After that, I developed a great love for saxophonists who could make all kinds of crazy noise in their jazz-type music and incorporate it into more so-called normal jazz. I’m talking about the harmonic extensions of people like Eric Dolphy, John Coltrane and Ornette Coleman. Hearing Allan Holdsworth and Terje Rypdal for the first time also resulted in a huge leap forward for me. I discovered you could make all these noises that could last indefinitely with interesting delay units and other technologies. Then I discovered that this was in fact a tradition that linked back to Terry Riley. Next, I found out Robert Fripp was already established doing this stuff. From there, it’s been wide open space until now. These days, there are so many things that influence me. I’m also back to listening to flamenco music all the time. Flamenco guitarists are some of the greatest players in the world, including people like Juan and Pepé Habichuela, Vicente Amigo, Paco de Lucia, Javier Conde, and Rafael Riquen. I also think a lot of the integrationists are remarkable, such as Miroslav Tadic, Marc Ribot, Eliot Sharp, Vernon Reid, and Raoul Björkenheim.

You believe electric guitar playing is at its most conservative period now. Why?

Development in the electric guitar realm has ground to a halt. Perhaps it’s inevitable that the guitar became a functional element of the rock sound rather than an expressive element. There is still a fantastic amount of music being made, but it seems the distribution and information pertaining to that music has become more and more slender. There are short periods of time when things from the underground show up and get absorbed by the overground. Then the underground starts building something new that’s more culturally reflective. But it seems like the industry of popular music has focused a larger and larger percentage of its money on a smaller and smaller segment of so-called artists. That’s a reflection of why an instrument as expressive and rebellious as the electric guitar has faded in importance.

The electric guitar has begun a kind of classicization phase and that really bugs me. I’m involved in a lot of Internet forums and it’s remarkable how many electric guitarists out there feel the need to recreate the great sounds of a very recent past, rather than honor the intentions of the great players which were to develop a unique voice, say something musically important, and break down cultural barriers. Things have become pretty staid and part of that is tied up to the need to sell instruments, amplifiers, effects, and even guitar magazines. Again, the focus of these universes is replicating past sounds, not the future. Very few new things have been developed that really take advantage of the possible future of the electric guitar as a living instrument. It feels like it’s heading towards being the next classical piano. For some people, there’s nothing wrong with that, but for me, that direction has removed the punk-assed, rebellious and almost political nature of what the electric guitar is.

Part of your personal solution is to think of yourself as a conceiver of music, rather than someone who merely plays an instrument. Elaborate on that.

Don Cherry used to say something to me over and over again when we played together near the beginning of my career, which was “Play the role of whatever sound comes into your head. If you think you should sound like a sarod player here, be a sarod player here. If you think you should be a wall of noise here, be that. Don’t worry about all this ‘I’m a guitar player’ crap.” That was good advice. Guitar still plays a pretty dear part in my creative process. I still love playing the instrument. In fact, I’ve been practicing on the guitar a lot in recent years. I’m still taking advantage of writing somewhat on the guitar or from the guitar. I might use it to create a series of rhythm tracks or textural events, but when someone hears them, they don’t know how they were made given my affinity for sonic manipulation. So, guitar can serve as the means towards an even more creative end for me.

Sussan Deyhim called you “the most sampled man after James Brown.” I understand that status has been less than a pleasurable experience for you.

The reason what she says may be the case is because I offered to the world in a commercial context several sample discs that were unique at the time of release. The sample disc manufacturers determined that the ratio of theft to actual purchases of those discs is 10 thefts for every sale. That’s not unusual in the world we live in where there is a pervasive public attitude of entitlement when it comes to copyrighted, creative ephemeral material like music. It’s a misplaced view, but the more people who sample your music illegally and the wider the distribution of the end product, be it a CD or film, the more likely that copyright issue will come to a court and be decided in the copyright holder’s favor.

When I discovered the depth to which my sample material was being used and how little I was being compensated in relation, I divorced myself from that world. I don’t want to spend my life in court or calling people asking them to stop doing what they’re doing. I used to call the musicians on a friendly basis and ask them not to use the samples illegally, which bore no fruit at all. I thought that was strange because I took a fair, musician community-minded approach. I was inevitably rebuffed, until the matters came into the hands of lawyers. I don’t have the time or attention span to pick up on all of the illegal usages, unless it’s a matter of something in the very broad public perspective. An example of that is my eventual co-authorship of the Madonna song “What it Feels Like for a Girl” from her album Music which sampled a substantial melody and ambient material from my Cloud About Mercury record. I think it’s fine to do this stuff, but clear it in advance, and compensate the person whose work you’re mining.

Reflect on Cloud About Mercury and what you achieved with it.

I look back at it with great pride. It’s a product of its time and I wish the mixes sounded a little crisper and broader, particularly on the drum and bass side of things, but as a whole, it was a benchmark moment for me. It represented the first culmination of a particular sound I had in my head. It achieved an idea I conceived of without dismantling the individual players’ input. The record has a sound I don’t think anybody else has ever made. It features a blend of a real improvisational attitude that takes into account slightly developed jazz-like harmonic events as a way to focus the randomness of the more ambient movement happening in the music. It also has some teeth to it. The album put me on the map. It’s a small map, but it definitely placed me there. The album circulated widely amongst my musical peers and many fans too. People sat up and said “This guy’s a bit different.” It lit a bunch of fires for me that sustain to this day. The record is still in print and continues to sell, which is amazing. It was a tremendous success across the board.

How did dealing with the brain tumor affect your creative outlook?

I think once I could get rolling again, it created a desire to make as much music as I can before this very short period of time we have allotted to us—and that goes for everyone—goes away. It’s not a small thing to recognize your mortality. When your life really flashes before your eyes, it’s time to figure out what’s really important to you. And what’s really important to me is to respect myself as a human being and the way I interact with others. I’m deeply interested in feeling like I’m doing the right thing, being a good person, and leading a life that is respectable and humane. I want that reflected in the intent of my creative output too. The other interesting thing is that it’s been discovered that the right ear and left ear are different. The right ear is more capable of understanding speech and words, whereas the left ear is more capable of perceiving music and tone. It hit me that maybe I play and hear music better than I ever did since this thing happened and I lost the hearing in my right ear. I don’t know if it’s an actual fact, but I look at it as an idea and think “Whoa, I wonder if that’s possible?”

The feeling of being absolutely stricken down and not even being 40 was also on my mind when I began my next solo album. I had to use a concept like God to describe the thoughts I was considering. Since my youth, I’ve had a background interest in religion and ethics. At one point I thought I should study to become a monk. I took the Buddhist vows a long time ago, but I’m not a religious person in any classical sense. However, I felt going through the tumor experience was like tripping on a thing in the road, and that thing was God. So the title Tripping Over God for the 1995 CD sounded just about right. It has a bittersweet nature to it and reflects the darkness and feeling of vulnerability I had at the time. I also felt like I no longer had to consider anyone else’s commercial or musical needs, except my own instincts. It didn’t matter anymore if what I did was considered cool or not. Those feelings have carried forward to this day.

How does spirituality inform your output?

Religion, ethics and philosophies are merely forms and nothing else. Music is the form I respond to most. Whether it’s highly sophisticated, thought-out music or spontaneous and not thought-out, the music I’m most attracted to usually has some kind of reflection of the musicians’ feelings about life and relationships, which I guess is what spirituality is. The path of being a musician is inherently spiritual because it connects people together. And when it’s done with commitment, intensity and intention, it brings something out of us that we could not express in any other way in our lives. I believe there are very, very strong forces at work in the universe that we don’t see everyday. And I think perhaps spirituality goes beyond the practical applications of being cognizant, giving and humane, but those are the ways I choose to acknowledge those forces. Maybe one of the great lessons of music is not trying to answer questions like “How do we make music? How complex is this thing that we do? Is music a matter of beauty versus ugliness?” Rather, music has the capability of uplifting the human spirit like no other art form does. The shaping of sound is an ephemeral process that we can’t hold onto, yet we experience these indicators that guide our creativity, and for me define how I see spirituality and how I design the way I live my life.

What evolution did the electronica-influenced Oah, released under the name Splattercell, represent for you?

I see it as a direct outgrowth of everything preceding it. From 1992 onwards, I was increasingly involved with taking spontaneous musical events I had recorded and further manipulating them as part of my compositional and technical palette. Most of the material on the record is built out of things that were originally improvised by me alone or me with other people. I went through the tapes, found stuff I liked and built pieces out of them. The energy of self-referencing creativity was the first impulse of Splattercell. As a composer, I’m a guy with a digital audio workstation and I used it to rethink what was played. I wasn’t fixing what was played, but taking the best of it that appealed to me in the same way that a guy writing a hip-hop tune bases things on samples of other people. The album built on the music I made on my previous album, What Means Solid, Traveller? However, I didn’t want any more of my records showing up in jazz or New Age bins and having first-time listeners throw the album away because it didn’t fit into their conceptions. So, I invoked the very transparent subterfuge of releasing it as Splattercell and hung the electronica genre on it. It would have sounded the same had I released it under the name David Torn.

You’ve been involved in a wide array of film projects. What makes the soundtrack universe so gratifying for you?

There’s something incredibly focusing about it. You have a need to focus on your own creativity, but also to amplify something happening in the movie, or a third person’s perspective that provides connecting elements or an overall flavor. You’re often contributing a critical emotional element that influences what’s going on and it’s really fascinating to try and create it. There’s also the additional focusing element of the directors. They aren’t necessarily educated about the tools required to make the music happen in order to have it convey something emotionally in a specific scene or across a wide, two-hour arc that pays off in the end when the film is over. The directors usually don’t have the ability to say “You need to use a major chord here and a minor chord there.” It’s very interesting to be a conduit for what they’re trying to get out of the picture. So, the focus and concentration, and even rewriting things over and over again to achieve an aim can be satisfying. The film world also allows me to write music that’s performed by orchestral instrumentalists and singers. There’s no other opportunity for that to occur for me, except maybe for a single record every few years on a label like ECM. Ultimately, the moment of gratification is enormous when you get to the end of a film project and you’re on the recording stage with the director and film company saying they’re happy with what you’ve achieved. It’s made me want to continue pursuing this universe in a very serious way.

Between 2002 and 2006, you mostly focused on soundtrack work and collaborations before reemerging as a solo artist and touring act with Prezens in 2007. What drew you back to those realms?

I was pushed out of the cave slowly, steadily and increasingly vocally by Tim Berne. He relentlessly invited me to play with his bands. I told him I only wanted to do gigs that were completely improvised because the other parts of my career at this point, particularly film music, are focused on composing and organizing music. It doesn’t have the danger of improvising in real time and creating music that couldn’t be made in any other way. After performing in various line-ups with Tim, he suggested I work with members of his group Science Friction that also included Craig Taborn on keyboards and Tom Rainey on drums. He said he thought this combination of musicians could really be special. So we worked together and I had such an amazing time. It didn’t take me long to tell Tim “This could be a whole new thing for me.”

Describe what’s special about the Prezens band’s chemistry.

It boils down to trust between the players. The ability to listen well is an act of trust. Every person in the band is fully capable of going forward and making something musical happen out of nothing. There are no constraints with this band and I don’t have to worry about whether I’m a jazz, rock or whatever player. Everyone is able to morph one type of music into another and not have it feel like an unnatural event. It happens without force or prefabricated conceptualizing. It’s not unusual for me to be doing something polytonal and spacey and then go into something that sounds like country music. And the band doesn’t see it as a sarcastic or cynical comment on country music. Rather, they see and feel the shift and do something with it. It’s the transitions between styles that are so thrilling with the band. There’s a constant, phenomenal feeling of “How the hell did we get here? What kind of spaceship are we on and where are we flying to?” [laughs]

There’s a deconstructive element in the making of the Prezens album. Compare it to your approach on Oah.

Oah was a bunch of musical events that were improvised, reorganized and then improvised on again. Prezens has similarities, but comes out of a live context that found me sampling the entire band, treating those sounds and incorporating them back into the music in a way that doesn’t break the musical flow. Previously, I mostly did that with my own guitar playing. With the Prezens band, I sensed the greatest opportunity to take that to the next level by incorporating all of the musicians into the process because of their openness and adaptability. So, when making the album, I had every musician and amplifier miced. I had their playing come through my gear so I could sample any combination of people during our improvisations, and manipulate what was happening in the room as it was happening. I also had the benefit of lots of additional technology that was too expensive to take on the road.

We played for two-and-a-half days and I took all the material home and went through the recordings on-and-off for a couple of months before I started to work on them. There’s a lot less post-production than people might suspect because of how the band itself excels at making seamless transitions between sections and genres. So, my focus was on finding contiguous pieces of music and working with those. When I located them, I would mildly reshape the music by inserting a section after an improvisation, adding a riff here and an overdub there, and that’s how the record came to be. I’m very proud of it. It represents and validates my leanings in a really personal way.

One gets the feeling that even after so many diverse projects and collaborations, you still view music as something with endless possibilities.

Absolutely and without question. Every single day I get a new idea in my head that I know I have to pursue. Going with fresh ideas also fuels my film work. No matter what the sonic motif or idiom of the movie is I’m working on, I always think “I don’t want to do the same thing I did last time. I’m going to be unhappy if I spit out industrial, assembly line garbage. So, what can I do differently now?” I think my dignity is somehow tied up in this. I need to be able to look back at a project, and regardless of what the money or circumstances were, or whether the final product is great or sucks, know that I can respect the process I used to put the music together. That integrity extends to the live arena too. When you play live in the way the Prezens band does, there’s no tomorrow. This is it, right here, right now. You have to be present in the moment and there’s no going back to fix something in the mix. The reward is totally immediate and unlike anything else. I really love it. It’s as though you’re refracting light from a spiritual prism.

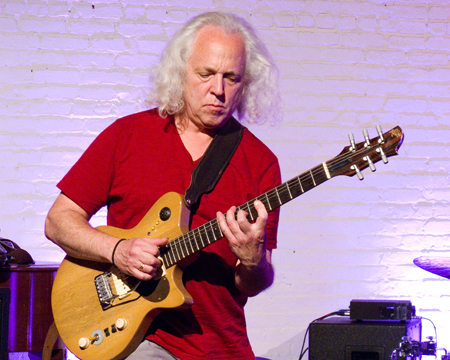

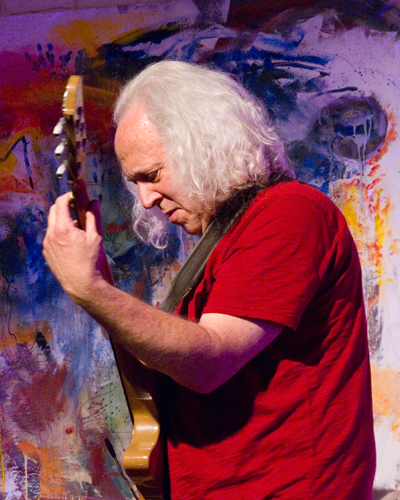

Portrait by Paolo Soriani. Live photos by Scott Friedlander.

Website:

David Torn