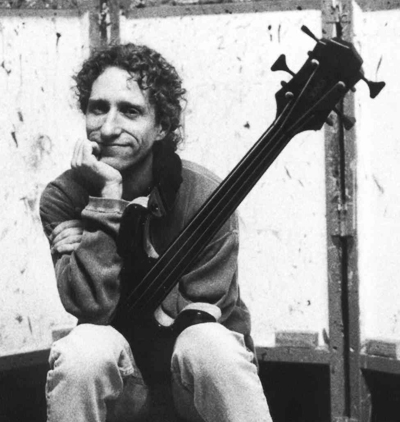

Michael Manring

Beyond Genres

by Anil Prasad

Copyright © 1993 Anil Prasad.

I take an almost adolescent delight in trying to challenge preconceptions. If we hold on to preconceptions, we do music a disservice and conceal a lot of creative choices. I'd like to see music evolve beyond genres and niches," says Michael Manring. The electric bass virtuoso is certainly doing his part in making that vision come true.

Manring’s latest album Thonk is an expansive, metal-tinged effort that departs radically from his previous efforts. As one of the first artists signed to Windham Hill records, his early output required a degree of conformity to its new age reputation. Albums such as Unusual Weather and Drastic Measures feature many elegant compositions and impressive performances, but Manring admits they only scratched the surface of his musical psyche.

The new album’s approach digs deeper into his true leanings. It combines hard rock, jazz and funk influences into a fresh, new sound. Helping Manring out on the album are a few musicians who know a thing or two about genre-blurring themselves: guitarists Steve Morse and Alex Skolnick, and drummer Herb Alexander.

Thonk adheres to Manring’s long-standing desire to "show that the bass is a vital and expressive instrument which has a great deal to say." Throughout the record, he employs a one-of-a-kind blend of tapping, harmonics and altered tunings, largely performed on his Zon Hyperbass. It’s a revolutionary instrument that allows him to quickly rifle through more than 100 different tunings in a single piece if he’s so inclined.

This interview features an in-depth look at the making of Thonk, as well as Manring's extensive thoughts on how the bass guitar is positioned in today’s music industry.

Thonk marks a real change of direction for you.

Yeah, most of it is pretty darn crunchy. We have Steve Morse, Alex Skolnick from Testament, Herb from Primus, and Steve Smith from Vital Information on it. Phil Aaberg came in and played on a tune and did some real nice piano stuff. So, there is a Windham Hill element there. We think we may have created the first ever New Age-death-metal-fusion record. We're definitely on that track. I don't know if we accomplished that, but we're mighty close if we haven't. All the elements are there in each piece. Some of the pieces are a lot grittier than others, but all the ensemble stuff, except for one piece, has some kind of grinding guitar sound, most of which I actually did on my bass. It's the first time I've ever played my bass through a Marshall stack. It was cranked loud enough to melt the walls. [laughs] If you put enough distortion on anything, it'll sound like a guitar. Because the Hyperbass is fretless, there's all kinds of bends and stuff you can do. There's some points where I'm trading licks with Morse. It's an interesting texture and a heck of a lot of fun. I get to have the adolescence I never had.

On my last records, things have been very consciously restrained and taste has really been the modus operandi—the conscious goal. We weren't going to do anything that was too over the top and we were really going to hold things back [in a hushed voice] and really go for restraint and intimacy and stuff like that. I seem to have a passion for breaking my own rules. There are times where I guess taste is no longer tasteful. [laughs]

How did the collaboration with Steve Morse come about?

I opened for his group a bit last year and we became friends and hung out. I've run into him several times since and talked to him about playing on the record and he said he'd be glad to do it. It turned out really well. It was really nice. He said some really nice things about the music and I felt very flattered having that come from him. He was really excited to play on it and he just sounded great. That guy's unbelievable. He sounds fantastic on the disc. I let him follow me on the trades. I wasn't about to follow that guy! [laughs] He made the pieces come alive. I had him play on the most jazzy stuff, not on the real thrashy stuff. It's not really what you'd expect and that's kind of the whole point of the record.

Alex Skolnick is another interesting guitarist choice.

Alex is not what you'd expect from a heavy metal guitar player. He's a very, very polite and down to earth person. He quit Testament because he felt a little musically limited. Of course, he's a heavy metal guitar player first and foremost, but there's a lot more to him than that. So, he was really glad to do this project because it allowed him to try other things and use aspects of his musical personality that haven't come forth before. That's one of the reasons we really wanted him. We also wanted to be able to go from the classic heavy metal grind in one bar to something that's reminiscent of bebop lines in the next bar to some classic rock licks in the next bar. He was really perfect for that kind of thing. He has all that under his belt.

Why have you avoided electric guitar on previous records?

I've wanted the bass to occupy that territory. But Thonk says "We can co-exist" and "Hey, you guitar players aren't the only ones that can wank." [laughs] We bass players have been backing up guitar players all these years—watching them come and go. We’ve seen the geniuses and the fools, and I'd like to believe we can be considered on the same plane—that we can be allowed to be geniuses and fools as well. So, there's all kinds of bass playing on the record and that's really important to me. As you probably know, there's a real split between bassists about whether you should be a groover or whether you should be a soloist and I'm just really uncomfortable with that and that sense of dichotomy. We all have to be both and we all have to have a killer groove and be able to play in a rhythm section and we also have to do other things. Obviously, some people are better at one than the other and that's fine. But I think we have to appreciate and develop both sides of the bass. By no means is the bass fully developed. We've just barely begun to scratch the surface of what it's capable of. I think it's very important to expand the sound of the instrument while maintaining the sense of roots. That's what it's all about for me. So, there's some very basic, very rooted playing, some completely over-the-top silly stuff, a lot of Hyperbass stuff, a lot of straight fretless stuff and a lot of stuff with the EBow.

Does the direction of the new album reflect your listening tastes?

Somewhat. I've always listened to a wide variety of stuff including Faith No More, Primus, Buckethead and Pantera. Mostly, this record comes out of a desire to have some fun. Plus, I got a fair amount of attention from the last record and I don't want to get too sterile. That gets really dangerous—especially with that kind of music. A lot of my peers seem to get locked into a thing and it just seems to be musical death. Before you know it, it becomes elevator music. I'd like to be a little older before that happens. I'm 32, so I've got a little while. One more shot to rock! [laughs]

There's actually a lot of really mellow stuff on this record too, oddly enough. Some of the solo stuff is pretty mellow. I wrote a new solo piece in which I figured out how to use two EBows at the same time. You kinda have to see it to appreciate it. There's also a piece that involves using the Hyperbass that definitely has the most re-tuning I've ever done. I have to count up how many times the bass is re-tuned during the piece, but it's probably over 100. It's funny, because that piece is fun to play. It's a mellow, pretty thing, but there's a lot of re-tuning. That's what the Hyperbass is for. Most of the ensemble stuff is pretty crunchy, but most of the solo stuff is fairly mellow.

How did you hook up with producer John Cuniberti for Thonk?

Somebody got his name and sent in my demo to see if he'd be interested. Turns out he was really interested and offered us a really good price—especially considering that he has platinum records on his wall. He was really dedicated to the project and it's really been helpful having him involved because he's real good. Of course, he's an expert at getting really great electric guitar sounds and stuff. It was new territory for both of us. He doesn't know much about jazz at all. He's coming much more from a rock perspective. He’s the guy that produced all of Joe Satriani's records. He's also produced Dead Kennedys and George Lynch. We managed to teach each other a lot of things. He's never done a bass record before and he said he never wanted to do one before. He never thought it was worth it, but he was really excited about doing this. It was really good for me because he really believed in it and believed that we were saying something that needed to be said. It was exciting and fun—a good collaboration I think.

Will Thonk’s album art be an improvement on Drastic Measures?

I sure hope so! [laughs] That's the one aspect I've never been able to get anywhere with. Actually, for Drastic Measures, that was the best we could do. There were many worse covers proposed for that—like my other covers! They're talking about that now and I think they're gonna allow us to contract outside of Windham Hill for the cover. Although, I'm sure they'll still put the album in the New Age bin. But I dunno. I've kind of enjoyed that—seeing it in the New Age bins. I suppose that's kind of an immature thing, but there's something very entertaining about going into the New Age bin and finding a record with Alex Skolnick on it. I'm afraid I've never paid much attention to my image. I think that's lost on me. I think everyone's given up on me in that regard. I'm very happy about that.

So, no more white suits?

Yeah! [laughs] I think they've given up on that idea too.

Was that attire Windham Hill's idea?

Of course! What a great interview. This is stuff I've always needed to say. That was an interesting photo shoot. I showed up wearing what I was wearing and they handed me this white suit. I said "Well, I'm not really comfortable with this" and the heavies come in and say, "This is the way it's got to be." Then they talk about demographics and this and that and they promise you certain things. I'm not much of an arguer. To tell you the truth, that whole aspect of the business—the image thing—is something I could never get very excited about. If they want to dress me up in a white suit, I don't care, you know? Just get the darn record in the stores and let me play. I guess half of what I do is pretty detrimental to my career. I'm having too much fun playing to pay attention to whether I'm appealing to the right demographic or not. I mean, it's probably a terrible idea to release a mostly thrash album at the moment.

Are you worried about alienating your established fan base?

Oh God, I definitely don't want to piss anyone off, but I have to do my thing. I'm sorry if I'm offending anybody, but I have to be true to myself. I suppose I'll probably alienate some people, but I have to do what I have to do. I'm hoping that people will take it in the spirit that it's meant to be taken in—just having a good time, enjoying myself.

What sort of label constraints were placed on you when making the last album?

With Drastic Measures, they were really hands off. They just let me and Steve Rodby organize everything. At the last minute, before we went to record, I went to the label and said "You guys have been really kind about this." They basically didn't say anything except "Just do what you need to do." So, we said "Is there anything we can do musically to make this thing work for you?" and "Is there any way we can cater to you on this?" You know, just to be professional. And they said "Yeah, one thing that would really help us out is if you could give us a cover tune because we think we can get it on radio." So, I thought that sounded kind of weird, but we thought we would give it a try. That's how we ended up doing the Police’s "Spirits In The Material World." Of course, it ended up not really being a hit in the end. [laughs] I don't think radio ever played it, but Windham Hill was very happy to have it. So, I had their input voluntarily. They keep getting better with each record.

That’s surprising to hear. I assumed that the label played a more active role.

My only regret at this point is that I've always wanted to do an all-bass record. I've got all the tunes and I'm really anxious to do it, but they won't let me do that yet. It's just a symptom of a greater disease. It's amazing how much discrimination there is towards the bass overall. It's kind of a shock. There's an awful lot of clubs that have basically told us that if I played guitar, they'd have me there every couple of months. As it is, they won't book me at all. And, you run into these kind of ideas over and over and it doesn't matter if you have good shows and great reviews. Even if you have a video to show them that it's a good show, they're still really scared of that idea of the bass. And that kind of mentality extends all throughout the music business.

Producers are really afraid of putting anything other than the most traditional kinds of bass parts on a record. I think bassists kind of haven't realized how constrictive the whole business is towards them. It's really pretty bad. It's kind of weird to use the word "discrimination" but it's really kind of like that. It's really kind of strange. So, Windham Hill's point of view is that they don't think they could get any airplay on it and there wouldn't be a big enough tour. There's really a stigma around the bass that I never hear anybody ever talk about. I'm kind of hoping that bassists will think about that and if we're kind of clear enough on it ourselves—that we have an instrument that's worth listening to—we can make other people listen to it as well.

The dichotomy you describe also exists within the bass community itself.

Boy, you're right about that. I didn't want to be the one to bring it up, but I think you're right. I mean, there's an awful lot of bass players that don't seem to mind that you can't hear them when you go to the concerts at all. You can't hear them in the mix regardless of what they're playing. It's kind of scary. As long as that's the case, someone, somewhere is gonna figure out that you don't need bass or bass players anymore. Why pay another guy when you can't hear him and he's not doing anything particularly vital anyway? So, I think for us bassists, we really have to make sure the instrument is really growing and that we have a really proud tradition and that we're really contributing to music. The situation is such a shame, because it's such a wonderful sound. Hopefully, things will start to change if enough people try to keep the thing growing and really try to fight for recognition. With everything I do, that's sort of my main goal—trying to establish some sense of the bass as a real instrument.

It seems to be a scenario pretty much exclusive to the rock and pop realms.

Yeah. In the classical music world, it's no more unusual to hear a solo cello concert than it is to hear a solo bass concert. In fact, there are a number of guys that make their living playing solo string bass, which is a pretty darn low and ponderous instrument. [laughs]

I'd like you to reflect on each of your first three solo albums. Let’s start with Unusual Weather.

I never really got what I was looking for from those solo records—something that really feels like me. I guess Unusual Weather comes closest to realizing the vision that I had wanted to realize. At the time, neither I nor the producer Bob Read had the ability to pull off much technically. [laughs] We struggled over that. I think largely the vibe and intent of the record came out well. I think we wanted to make a real pleasant-sounding record that presented a single mood—an honest, folkie, kind of jazz record. Almost all the instruments were either me or Bob Read. So, all the technical aspects of that record were a big challenge in terms of our playing, the recording quality—all of that kind of stuff. Our hearts were in our right places, but it was hard to get our hands and chops to follow.

Next up is Toward The Center Of The Night.

I did almost all of that one myself. I produced it and played most of the instruments. That was very challenging. I don't know if I'd do that again. That was a lot of stuff to do. I was sort of reclusive at that time. I did all that while I was in Montreux. I didn't get a chance to listen to much music or anything that was going on in the outside world. I was pretty much living in my own little world at that point. That one did really well on radio and that was good for what it was. It really didn't feel like it came out like I wanted it to, but I'm really proud of some of the compositions on there and that one definitely had more altered tunings than on my other records. I had some good ideas, but it kinda wasn't there—it wasn't quite there. I'm not a very good producer. I think that was what that record suffered from the most. Had there been a really great producer, I think it could have been a much better record.

That brings us to Drastic Measures.

It was really great working with Steve Rodby on that. He's a really good friend and a great musician. We had a really good time doing that. That one was really nice because I can pretty much listen to the whole thing without cringing—although there are some moments. [laughs] I feel like it pretty much says what we wanted it to say and it sounds pretty good. It all came together pretty well. That's a good feeling because it kind of made me feel "Okay, we did that and now I can go and do something else weird and look for what else is out there."

Is there a philosophy you adhere to when making albums?

Basically, I think of records as going on a trip. You can either go down to the mall and see the same 60 stores as in every other mall or go some place completely weird like Bora Bora—where you have no idea what's there and maybe have a great time or a lousy time or a little of both. That's how I approach records. You try things and see what happens. You see what's out there, experiment and learn. I don't know if I'll ever make a record that's perfect. I'm not sure I'd ever want to make a record that's a perfect representation of who I am or where I am and why. Records capture a moment in time. They're a chance to explore, learn and goof around.

Given the difficulties in promoting bass-oriented music, how did you convince Windham Hill to take you on as a solo artist?

I think it may very well have been naiveté on their part. No-one ever told them that you weren't supposed to sign bass players to a label—they just liked my music and thought it was nice stuff and gave me a record deal. But as we were talking about, there's a real stigma around bass in the music business. People really want bass to be a certain thing and they're really reluctant to let it be something else. I think people sometimes think of it as an old idea. They say things like "Well in the ‘70s, we entertained the idea that bass could play a solo, but this is something we're not going to allow now because the economic climate isn't safe enough." I don't think it's a conspiracy, but it's close. [laughs] There's a real sense of fear that people have and it comes less from a fear of the bass than a fear of change in music and a fear of growth and allowing something different to happen. And a lot of it is good old-fashioned ‘80s greed. They can make a lot more money selling pop music than somebody trying to do something creative on an instrumental record. It's really a shame.

I sincerely doubt there are less creative people in the world today. I'm sure that number is constant, but the music business has managed to push creativity into a corner and keep it there. We've had too many guys try to do things on guitars and saxophones. Guys on bass and other instruments are getting overlooked. For instance, my friend Paul McCandless, who's just a brilliant oboe player, finds it pretty challenging to get across to people. So, he gets a lot of pressure to play saxophone which is an instrument that people can understand—an acceptable jazz instrument. In the ‘70s, there was at least a sense of there being an alternative. Pop music was pop music and it was pretty much dreck and everyone accepted that and that's all there was to it. But there were other things to listen to if you wanted to listen to something a little bit deeper. Somehow, we kind of lost that.

At this point, pop music is sort of hip, but we've kind of ended up with no alternative music. What we've been calling alternative music or alternative rock is now mainstream, yet it's still called alternative. Therefore, we don't have anything that's alternative anymore. So, there's nothing for people to listen to if you don't happen to like what's on the radio. And what's on the radio is pretty much computer-programmed. I think a lot of people don't realize that a lot of the pop shows they're going to see are actually a computer program running from top to bottom and that the musicians onstage aren't actually playing an instrument and are just there for show. Also, the radio stations they listen to—the DJ's have no control over what music is being played. It's all figured out by computer. Most people don't realize what a business the whole thing has become. What does that say about the development of our culture? I guess the really scary thing about it is that I don't hear any dissenting voices. In the ‘70s you could walk up to somebody and say "I hate the Bee Gees!" and you knew you were going to piss them off or you were going to have a great conversation with them right there. [laughs]

The Hyperbass is a unique instrument in that it lets you switch tunings on the fly. What attracts you to that idea?

That aspect came about because I've been into altered tunings for years and years. I got to the point that when I would play a solo concert and every piece would be in a different tuning. So, it occurred to me that the next step would be to change tunings within a piece. Each piece then has its whole own little world—its own little reality. When you change the tuning of the bass, it really changes the whole sonority of the instrument—it gives it a whole different character. That's always nice in a solo show especially, because people are worried about it all sounding the same. When you tell someone you're going to play a bass solo concert, they think it's gonna be the same sound from beginning to end, so changing the tuning changes the sound of the bass. So, if I'm gonna change after every piece, why not change within the piece? So, I started by cranking the tuning keys while I was playing, and got pretty good at that. I wrote a couple of pieces that involve that. It's real hard, but I got to the point where I could do it. I had to have the bass set up just right and everything. But then I realized that most of the situations where I'm playing live—in a lot of these little clubs—the monitoring situations are so bad that you can't hear well enough to tell if you have another quarter turn to go. So, I realized I really needed an instrument that was designed for that—something that would make that a lot easier. Plus, I wanted to do a lot more with it. Obviously, I could only change the tuning one string at a time and had to keep one hand on the bass and turn the key with the other. So, that's how the Hyperbass came up in that regard. I still do some cranking of the keys to change the tuning but most of the tuning changes are done with the levers and switches.

Are the levers and switches entirely mechanical?

Yeah, but there's this new system out. Some guys actually have a servo-motor for tuning each string that's completely bizarre. They haven't made a bass yet, but they've promised me their first bass system. It'll be fantastically expensive, but it's about as bizarre as you can imagine. They only have two prototypes—they're Les Paul guitars. The whole back is hollowed out and there's a little servo-motor for each string and there's a little digital read-out on the guitar that tells you what tuning you're in. So, you hit a button on the floor and the whole guitar switches to a different tuning. They're still working on the bugs, but they're pretty darn close. Part of the problem—again—seems to be getting people to take the bass seriously. Companies that make stuff like that have very little impetus to make stuff like that at all, much less for bass. There are companies that have some amazing designs on the drawing board for bass stuff, but they just don't feel they could ever sell it because they don't think people would buy it.

How do you align your mind to work with a new tuning on the fly?

Mostly, it's a matter of learning to deal with the different intervals. Normally, when you look at the bass fingerboard, you think of each fret in each place—this is a C, this is an F—but when you change your tuning a lot, you think of ratios, and fortunately, it's always the same ratio between your open string and a closed note. So, you start thinking in that regard more and kind of see that relationship better. It's hard to improvise wailing stuff and fast notes, because all the patterns that your fingers have learned sound really funny now. But I can basically improvise little bits of stuff. Actually, you learn pretty fast where everything is—it comes together. I've been doing it a really long time, so I've gradually become used to it. But you know, I wouldn't try to play "Donna Lee" in some bizarre tuning.

Are you ambidextrous?

No, but I am kind of dyslexic though. [laughs] I remember being a little kid in first grade and having them tell us to say the "Pledge of Allegiance" and put our right hand over our hearts. I remember that being the hardest thing to do—trying to figure out which one was my right hand! [laughs] I don't generally do lots of things with my left hand differently. Of course, on this new record, I've had to top "Watson & Crick" with a piece where I play three basses at once. One of them I lay down on the table in front of me. In concert, I get a volunteer from the audience to hold it for me. It's really great what it does to your brain. It's very similar to psychedelic drugs. You have to concentrate a lot more. With drug use, you sit back and let it happen. With this activity, it's a lot more participatory—you have to make it happen! [laughs]

How are you playing three at once?

You kind of cycle around them. You get something happening on one and you let that ring and you go to the other and you get that going. It's like juggling. You pay attention to any two at the same time. The real appeal to me is what goes on in your brain. Especially because these pieces involve polyrhythms. In "Watson & Crick," it was mostly two against three. In the new piece, I wanted to expand on that. There's a lot of four against three, and five against three and some four against five. It's really an amazing feeling to get that going and to feel all that happening—hear both those rhythms at the same time. In fact, in a lot of cultures, it's that exact sensation—that sensation of polyrhythms—that they think of as a very high, spiritual state. In Africa, South America and Cuba, they use those kinds of polyrhythms to induce what they feel are the highest states of mind. I can see why.

What are the biggest challenges for bassists trying to develop a unique voice on their instrument?

The sensibility of the instrument is so unformed and undeveloped. If you're starting out as a bassist, it's really hard to get really good information about the instrument. You can get a lot of mixed messages about it. A lot of instruments are being made very poorly. The whole situation is really not very highly developed. I think it would be a challenge just to get to the point where you felt like you were given the opportunity to express yourself. It's a real challenge just to get to that point, whereas if you play violin and you show some talent, there are so many teachers who are available to nurture you and encourage you to express yourself. With an instrument like the bass, there's a lot of conflicting attitudes about it and a lot of misinformation.

There's a tremendous sense of preconception about the bass. It's the only instrument I've ever heard where people say "The role of the bass is..." and it's usually "The role of the bass is to work with the drums and support the rhythm section." And that's okay, but how come we never hear about "The role of the piano" or "The role of the guitar?" That kind of gets to you after awhile when you hear it over and over. While I don't rebel against that notion of the bass—the idea of working with the drums and really supporting the band—the fact is, there's more to the instrument than that. It's also a great solo instrument. It's incredibly hard to get over the stigma.

How do you look back at your time with Montreux?

I really enjoyed it. It was a great time. We had a lot of fun. To me it was a little disappointing because I thought the potential of the band was pretty much unlimited. We really had the full support of the record company and it was a really good time for that sort of music and everybody was a very good musician. But, I really thought we could have taken that band far. I feel in a sense we copped out a bit. We definitely did some fun stuff, but I felt we could have taken it to a whole new place and kept experimenting. We tried to make everyone an equal member and that's the way it was most of the time. I was definitely the guy coming from left field in the sense that I had more of a jazz and rock background. The other guys were coming from a folk and bluegrass background. Most of the time that wasn't a problem. All of us were interested in taking the music to new places. There were times when I think they would have liked to have kicked into some of the bluegrass tunes I didn't know. [laughs] But the goal of the band was to do something new—to try to get into a new vibe. There were some really great moments. We tried to keep it pretty darn open. We never quite got a real consensus all the time on everything, but we always tried to leave plenty of room for crazy improv. We were a lot better live I think. All this music is a lot better live. I certainly have always felt that I'm a lot more myself when I play live. Montreux was kind of a frustrating time though. We never managed to carve out much of a niche for ourselves, as opposed to some of the other people that did really extraordinarily well in that New Age genre during that short period of time.

During the Montreux era, the spotlight was much more on Windham Hill, rather than the individual artists. The joke at the time was the band was known as the "Windham Hill Samplers."

[laughs] I've never heard that one. That's great. Yeah, the signs and posters pretty much said in big, huge letters "Windham Hill" and in small letters "Artists: Montreux." As silly as that sounds, we got an awful lot of mileage out of that. I remember playing with Montreux in Appleton, Wisconsin before we had a record out—before there was even a name for the band. We had 2,000 people at the show! And that usually doesn't happen. As much as all of us would like to complain about being pigeonholed and being pinned against the wall, we got a lot of good stuff out of it, and to an extent, still are getting some good stuff out of it. But, we never lived that down. To tell you the truth, it didn't bother me much. I was having a good time playing and wanted to try a lot of different things. I think for some of the other folks, it really wore on them. I can definitely understand that. It's a drag after awhile.

Did you hook up with John Gorka through the label?

Exactly. I usually end up playing on pretty much anybody's record on the label that doesn't have a bassist already, and some that do actually! [laughs] I just end up getting the call, and that's how I met John. I've done a lot of touring with him. We're coming from two completely different places musically, but I love doing it—it's fun. It's such a strange pairing of musicians, but we both enjoy it. I've learned a lot playing with John, because he's such an intuitive musician. He knows the names of the chords he's playing, but that's about it. He's not fancy in any way, but he really is effective and communicates so much in his music. It's such a good reminder for a guy like me who grew up listening to all of the fusion wankers. [laughs] I've learned from John and am still learning that it's not about a lot of fast notes and fancy stuff. It's about communicating and saying something that people can appreciate. It's a mighty good lesson.

You were once in a disco band called Spectrum. What do you recall about the experience?

Geez, you have done your research. [laughs] Yeah, I went to the Berklee school of music for two semesters and got an offer to go on the road playing top-40 music, which in 1979, meant disco—stuff like "Boogie Oogie Oogie" and "Disco Inferno." I lasted about eight months with that. We were on the road constantly. Everybody in the band was from different cities and there was no home to go to—it was one gig after the other. Some gigs were one or two weeks long. For a starry-eyed 17-year-old kid it was pretty fun for a couple of weeks. But I quickly discovered that wasn't for me. It was a difficult situation. We had to play a lot—four sets a night. Some nights it was five sets. We went from 8:00 pm to 1:00 am. It was pretty tiring and you didn't want to play that much during the day. It was kind of destructive creatively in that regard—it sucked all the energy out of you. So, I really feel for my colleagues who do it that way. It's a tough job.

Another early gig was with a fusion band called Natural Bridge.

Yeah, I left Spectrum and went back to D.C. where I grew up. I just happened to luck into Natural Bridge which was a major fusion band in town at that time. We made a record but it was never released. We were recording for a label that was part of CBS at the time that did fusion stuff. But by the time we finished the record, the label was canceled by CBS and they pulled all of the fusion stuff. That was around 1980 or 1981. They just pulled the plug on that sort of music. It was really disappointing and really caused the break-up of the band because at that point we didn't know what direction to go. It was a pretty good band. We were definitely a fusion band but we weren't as soulless as a lot of the fusion bands at the time.

Was Michael Hedges an inspiration for your bass approach?

Certainly, without a doubt. But when I first met him, he was a Neil Young clone. [laughs] He was not at all considered a great guitar player by any means. As a matter of fact, if anyone had suggested at the time that he'd be considered one of Guitar Player’s 100 greatest guitar players of all time, he would have laughed. He was just a kind of folkie guy who strummed a guitar and was a little bit spacey. That's how things started when I met him. He was actually a little bit shy about approaching me because I was playing fusion at the time—something more complicated. But we had a lot of the same tastes in music. We liked rock'n'roll and jazz and a little of everything. So, we started playing together. I think we taught each other a lot. I think I received a lot more of the learning end than he did, but I remember showing things to him and he would take them and turn them into unbelievable stuff. I remember talking to him a lot about grooving and how the drums work in music. It was amazing to see him blossom into this incredible guitar player, because when I met him, he felt real bad that he couldn't play like Pat Martino—all of his friends could and they kind of looked down upon him because of that. But, then he took the guitar in a whole other direction. It was incredible to watch him develop and see how he followed his ideas through. We've been playing together for so long that a lot of the musical communication is very intuitive. It has a very improvised feel to it.

Have you considered touring as a duo again?

It'd be fun to do it, but it got kinda disappointing for awhile when we were playing a lot together. He would play a tune and go off and change his tuning and I would play a tune and go off and change my tuning. We would switch off that way. But people started kind of seeing it as a competition in the concert. That was really depressing. We thought people were completely missing the point of what we were trying to do. Our whole approach was to get away from that and just try to be good musicians. For awhile, we tried playing a whole night of really mellow stuff, but that didn't work either. That was kind of hard. I think it was hard on Michael too—he was disappointed with that too. We're both kind of sensitive towards that aspect of music. So, in a way it's kind of discouraged us. But, I think we'll end up doing something together and just get over it.

You once said "Americans are often skeptical of virtuosity, which of course they should be." Elaborate on that.

Virtuosity is a tricky thing. It's easy to boggle people's minds with music. Music is a very powerful force and it's easy to misuse it. It's easy to manipulate an audience. I think it's good to be skeptical of something that's fast and flashy and fancy. You have to ask "Yeah, but what does it mean?" There's more to music than being flashy. It has to be moving as well.