Donate to Innerviews

Since 1994, Innerviews has provided uncompromising, in-depth interviews with musicians across every genre imaginable. And it does that with no trackers, cookies, clickbait, or advertising.

Your donations are welcome to help continue its mission of highlighting incredible music and artists, without any commercial considerations.

Your contributions will be instantly transformed into stories and videos, and cover hosting and web management costs. Importantly, your dollars will help ensure Innerviews remains absolutely free to all visitors, independent of their ability to financially support it.

Please consider making a donation today by using the PayPal QR code below.

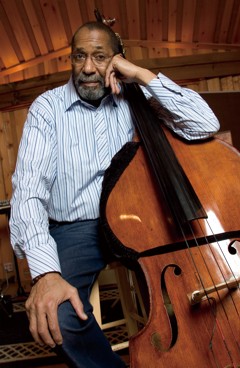

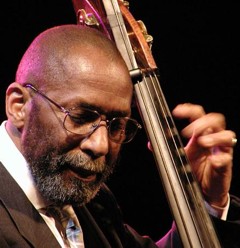

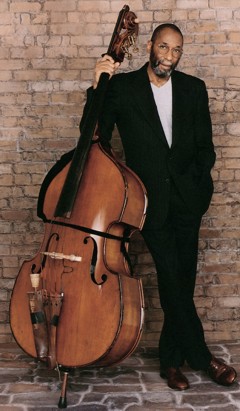

Ron Carter

Recasting the Past

by Anil Prasad

Copyright © 2008 Anil Prasad.

Without a doubt, Ron Carter is one of the foremost influences on bassists throughout the last five decades. His talents in going beyond the role of time-keeper and using his bass as a dominant force in directing a band’s music by modifying beats and harmonies on the fly set a standard few can match.

Carter has made 50 albums as a leader and performed on more than 2,000 others within an impressively wide spectrum of collaborative and sideman contexts. Eric Dolphy, Aretha Franklin, Antonio Carlos Jobim, Wes Montgomery, Kronos Quartet, Paul Simon, A Tribe Called Quest, and McCoy Tyner are just a handful of the luminaries that have sought out his services. But it’s Carter’s work as part of the legendary 1960s Miles Davis quintet that has made the most indelible imprint on his musical psyche, as evidenced by his latest album Dear Miles.

The disc finds Carter and his long-term group, comprised of pianist Stephen Scott, drummer Payton Crossley, and percussionist Roger Squitero, exploring key tracks from Davis’ 1950s and 1960s catalog such as “Seven Steps to Heaven,” “Someday My Prince Will Come,” and “Bags’ Groove.” The band infuses these and other classics with a nuanced and dynamic approach that expands their melodic palette and amps them up with propulsive, pulsing rhythms.

Two original Carter compositions reflective of his chosen Davis oeuvre round out the collection. The buoyant “Cut & Paste” is the most fun piece on the record, with its racing basslines and percussive piano accents. Dear Miles wraps up with the appropriately reflective, low-key grooves of “595,” which features piano figures reminiscent of “So What,” another Davis classic.

Describe the impetus to undertake a Miles Davis tribute project.

The idea to do this project and its title were the record company’s idea, not mine, but I certainly did buy into it. I thought it was time to do something like this. I’m 70 now and probably have fewer notes to play in the future than when I was 60. It certainly felt like it was time to make a comment about the kind of music I enjoyed playing during those many years with Miles. I think if Miles was still alive and heard my band playing this music, he would be appreciative of how it has developed over the past 40 years. I’ve avoided Miles Davis tribute records and groups for a long time, but the library of songs my band plays and those we’re interested in trying to develop and see where we can take them is the stuff I did during the Miles Davis period. The CD features a true working band, and that’s important to me. It contains some of the music we play every night and we really tried to make it interesting and fun for the audience to hear. I’m persistent in my attempt to ensure the songs have a life.

How did you go about picking the songs for Dear Miles?

The songs are ones that I enjoy playing with the band. The guys in the group looked to me to find out how I felt these songs could be most effective played with no trumpet. The arrangements we came up with during the course of the last three years were designed to make gigs, not so much for a record. It worked to our benefit that the CD opportunity came along when the band had just come off a tour. We were still really hot from that and it worked out really well.

I didn’t go back and listen to my work with Miles as part of the selection process. I wanted to be free of any kind of influence that may sneak into play as a result of listening to the original records when putting together an arrangement for this project. I don’t ever listen to those records. I hear them on the radio occasionally, but I don’t make a point to go out and buy one and revisit them. I have a lot of other interests and I allow those interests to dictate my listening time.

Provide some insight into the recording philosophy behind the record.

Every song is a first take. I think the more time you spend in the studio playing the same song over and over, the more the individual musicians lose focus. Instead of focusing on the overview and intent of the music, they get more focused on their solo and as each take goes on, the music becomes secondary to how they feel they can make their solo more important, better, or different. So, my view is we go in there and whatever happens on the first take is what we live with. The bottom line is jazz is about fresh ideas and if you get to take 25 of the same song, all the freshness is gone, no matter how talented the player is.

How would you describe your approach as a bandleader?

The important thing is the guys trust my judgment. However, if I say it’s too fast or too slow or let’s change keys and someone disagrees, they question it in a very adult way. Sometimes we may not be in the right place for a particular song and the band knows the floor is open to any suggestion. In fact, their input is almost mandatory. When you have a quartet, everyone has to have a say to a certain degree when it comes to the final product. I encourage them to disagree with me if they want to. I want to know what their view is because mine may not be right. There’s a real open-mindedness and open-endedness in discussing our song library which makes us always play well together.

What lessons did Miles teach you about being an effective bandleader?

With Miles, no night was a wasted night. You hear reviewers talking about how the first tune a band plays on any given night is a throwaway song. I never felt that when I played with Miles. When we played, whether it was the first song, the first night, or the last night, we were intent on playing the best we could and maintaining the standard we wanted to be held accountable for. Miles certainly made that important to me. I also watched how he didn’t manage the band to the point where we would only play the music his way. He didn’t make us feel our ideas weren’t important. He allowed us the flexibility to experiment if we saw fit, but made us aware of the big picture, which meant how good can the music as a whole sound, rather than how good can one individual sound in the band. Working with Miles was an intuitive process. He never told me what to play and never asked me how I was going to play it. He just trusted that I’d find the right way to make the song work out.

What are some of your favorite Miles Davis pieces, regardless of whether or not you played on them?

Any song from Kind of Blue. It’s such a historical, groundbreaking record and everyone should have it. The recorded sound is fabulous and the music is still stunning after five decades on the record racks. It is still one of the most important records in music history, including classical music. Everyone who reads this should go out and buy it.

Describe your creative process for me.

It’s not complicated. When I hear an idea in my head, I try to sit down and figure it out on the bass. I explore what the best chords are to make the song do something. I may also reach out to the piano to work things out. I’m not a bad piano player, but I’m not a very good one. I have enough skill on the instrument to allow me to get through a song to find out if I really need a melody at a certain point, or if there is a better chord that I can play to give the song a different flair than it has without it. It’s not so much about trial and error, but more about trusting my instincts and knowing that if I find a good way of doing something, that I know it’s right.

What happens after you’ve sifted through those initial ideas?

I still do things the old-fashioned way, and use a pencil, paper, and an eraser and notate everything. Next, I try to play it for the guys in the band. Hopefully, I have enough information on paper for them and there’s not too much need for verbal explanation of what I’m looking for. I may also play it to them to see if I’m on the right track or if I’m off-base to make an idea work. If I end up stumbling through something or a song is going the wrong way, I trust Stephen or Payton to let me know that maybe we should reverse the form, or perhaps have a different part as the first part, and use the first part as the second part. I trust their sense of being unafraid to tell me what’s right or wrong in their mind and we go from there.

In general, I try to make a song work so that it works even when I’m not standing next to whoever is playing it. To me, that’s the test of a good song—if you can have your band, or any band for that matter, play your music without you being there to guide them through the process. If you can get an idea formed well enough that no-one has to call you up to find out what you mean by this chord or this note, then you’ve got a good start to having your music played by someone else other than your band.

Have you ever been tempted to go the technology route to capture initial ideas or notate?

I have a computer and I’m familiar with how to operate it, but I don’t rely on it to make the songs work. I trust my senses, choices of notes, and musicality. I don’t feel I need a computer to get me out of a compositional jam. I think I come close enough to my point of view to have the song have some validity without needing the computer to help make it work for me.

What are the biggest challenges you face during your creative process?

My main concern is does the song have some value and if it doesn’t, why not? I’m a meat and potatoes guy when it comes to writing. I don’t spend time getting into the metaphysics of composition. I write what I hear and I trust that if it doesn’t work that I’ll find something else that does. I also don’t insist that because it’s my song that what I wrote is the best or only way to do it. My musical honesty will allow me to make the right choice and if it’s going the right way, my sense will let me know it’s okay. Occasionally, I get something that works well that allows me to quickly move to the next measure or phrase. However, if things aren’t going the right way, I don’t mind putting it on my desk, walking around for a couple of days, and trying it on another night or different day, or applying a different approach to it. If it’s still not worthwhile, I’ll put it on my bulletin board, but not throw it away. Stuff comes and goes and I think it’s a question of the luck of the draw if you can get an idea and go with it.

Overall, writing music is not that complicated to me. I think what needs to happen is people who write should study the art of composition. They need to find out how a song works from a mechanical perspective. I think a lot of guys who write now don’t take the time to do that. They feel they can do without outside help like lessons or books. I think those guys are making a mistake and missing the point of writing quality music. There’s nothing I can say that’s going to inspire someone to write the next “I Remember Clifford,” “Round Midnight,” or “Billy’s Bounce.” They’ve got to go out and study the music and a lot of guys don’t take the time to do that. I have no magic solution for those guys.

You once said a key to being an effective bassist to is to be flexible, yet authoritative. Elaborate on that for me.

Bassists have to understand that they are part of a group and it’s their function to make the group sound like the bassist belongs there. It’s also their responsibility to look around and find out what is going on with the particular group they’re in and what shape the music has. They should be able to play the changes in their head without needing the bass. They should have the confidence to help shape the music so it takes on a life of its own. They should be able to take charge of the band if the music is floundering. They should know when to step in and take a more active role and give the song a direction it’s not going in if they feel that’s the way it should go.

What advice do you have for bassists that are reticent to step out front like that?

Most bassists don’t know how the bass works. They usually don’t know harmony either. So, get a teacher and learn both. Get someone to show you theory and how the chords work too. Once you have a higher skill level, a better sense of harmony and theory, you’ll feel more comfortable understanding the possibilities of a song and playing the notes that can make the music go somewhere else. Harmony is tremendously important. If you don’t know harmony, you won’t know how to make your musical point of view strong enough to catch everyone’s attention.

Lessons are also important because bass players don’t always play good notes and sometimes no-one tells them that until it’s too late. There are certain sets of notes you have to play and if you keep playing the wrong ones, and no-one ever tells you that’s not quite right, you don’t get any better. So while you have to have the willingness to make mistakes and figure out why they don’t work, lessons go a long way to helping you do that.

You’ve been using the same 1910 Juzek bass since 1959. What makes it so essential to you?

Nothing has the same feel and played-in quality. I’ve started to find where the notes are located better than I did almost 40 years ago and I’m still determined to play this bass better than I’ve ever played it. I’m really starting to know how this bass works finally and I’ve developed a sound on the instrument that’s so identifiable because I’ve been using it so long. I think bass players should be careful when they’re looking for a bass. Don’t be impressed by its age or pedigree. Ask yourself if it can make a sound on the instrument that you can be held responsible for forever. Unfortunately, the cost of basses has gone through the roof and I’m afraid that a lot of players who play well are not having the chance to get better because they can’t afford the tools. It would be nice if there was a consortium of people who have money to dedicate and devote money to helping young players who are talented purchase instruments worthy of their potential.

During the ‘70s, you were known to play electric bass on occasion. What made you pick up the instrument?

It’s been about 30 years since I played one. I remember having to buy one—a Danelectro—because the studios were making demands on upright players to have that instrument in their hands so the producer could have another choice of sounds. The electric bass was new to me and I simply picked the lightest-weight bass that I could carry around with my upright. I wasn’t forced to play electric bass but I wanted to work as necessary during that period.

You’ve also dipped your toes in hip-hop by playing on A Tribe Called Quest’s "Verses from the Abstract" and MC Solaar’s “Un Ange En Danger.” How did those opportunities come about?

In both cases, they called me to see if I would be available to work on their projects and I didn’t know their names or follow their music. So, I found someone who I felt was attuned to that community and they said the young men involved are very interested in music and song forms, although their records don’t indicate that. I was happy that they were eager enough to get in touch and felt that I could contribute to their music, so I took the offers. I had a good time playing with them.

What did you make of the end results?

I only saw a part of the MC Solaar video last month in passing at a store in Europe, but I didn’t really have a chance to listen to it. I just bought the Tribe Called Quest Low End Theory album only two days ago as a matter of fact. So, I haven’t heard any of that music with any view. I know the Tribe Called Quest record made a lot of noise in that particular community and is called one of the seminal records of its decade. I’m happy to be part of that situation and be associated with those kinds of historical views. However, my general feeling is those hip-hop and rap records are based on rhythm and not so much on songs and music. I’d like to see those guys sit down and think about what kind of song would their words match? I’m sure if they did it that way, they would use different kinds of lyrics.

Is there a spiritual side that informs your music?

I think every African-American in my age group grew up attending church. I’m sure that experience is somewhere to be found in my music although I haven’t made an effort to point it out. Some people think only singers went to church, but a lot of jazz musicians attended services as well and I’m aware of that environment. When we play with the band, we bring some of that experience and knowledge to any given gig. So along the way, I’m sure I’ve reached back into my experiences for a phrase I heard or sang in church.

When traveling by air, you sometimes checked in your bass as “M. Contrebasse” and had the bass occupy a seat in order to protect it. How has traveling with your bass worked out in the post -9/11 era?

The airlines have no sympathy. They don’t even let the bass on most airplanes. And in Europe, they sometimes change the planes for another one that’s too small for the fiddle, so you can’t get on that plane and have to wait for the next one. It’s a challenge because the airlines are unwilling to allow the bass to travel in the cargo hold and you have to learn how to make gigs work without their help. I don’t give the airlines any credibility to say anything logical to me about the bass. Whether the bass can travel depends on who’s working on the desk at that particular shift and you’re at their mercy. And there’s not a nice person there usually I assure you. It’s really difficult. I don’t know what our answer is in terms of being able to reliably travel from point A to point B to play our instruments. The airlines are really sticking it to us and my heart goes out to bass players who have to travel and have no way of circumventing the airlines’ awful attitude towards us.

How have you been coping with this dilemma?

I just came back from a tour and I borrowed a different bass for each of the eight concerts I played. It’s not pleasant but every night I have to find a way to make a strange bass sound not so strange or feel so strange. It’s like taking a lesson every night to find out how quickly I can adjust to a new bass and how I can make it sound close to mine so I can play some music. I don’t recommend anyone do this if they can avoid it. It’s so unfortunate that we’re being forced to not be able play on an instrument that does our talent justice, but no-one at the airline wants to hear that. They don’t understand that musicians are comfortable with their instrument and nothing else will do. In a way, I feel if I don’t have my own bass that I’m cheating the public because I can’t really do what they’re paying me to do. I’ve kind of got past that because this is clearly out of my hands. So, I try to play as well as I can with whatever bass has been put in front of me. I get a half an hour to say hello to it and my job is to make it sound like what the audience thinks my bass should sound like. I do the best I can in the circumstances.

You recently did a television ad for Tully’s Coffee in Japan, playing a song called “It’s the Time.” Tell me about that experience.

I’m all you see in the ad. I’m playing the bass, wearing a great suit and tie, and acknowledging that the coffee product is a very good coffee, which I use myself. I also did a trio record that’s named after the tune and features it. Mulgrew Miller and Russell Malone play on it and it will be out late spring. I don’t understand why I can't do an ad like that in the States. It blows me out of the water that this country can’t see any value in jazz other than the 20 people who come out to a club to see it. The CEOs and others that make decisions aren’t even aware that jazz exists. Yet, a country like Japan, whose population is smaller compared to that of the States, feels an African-American bass player can be a representative of their product. It’s really quite amazing. I’d love to do it for an American product, but jazz players don’t get those kinds of calls here.