Django Bates

Minature Worlds

by Anil Prasad

Copyright © 2019 Anil Prasad.

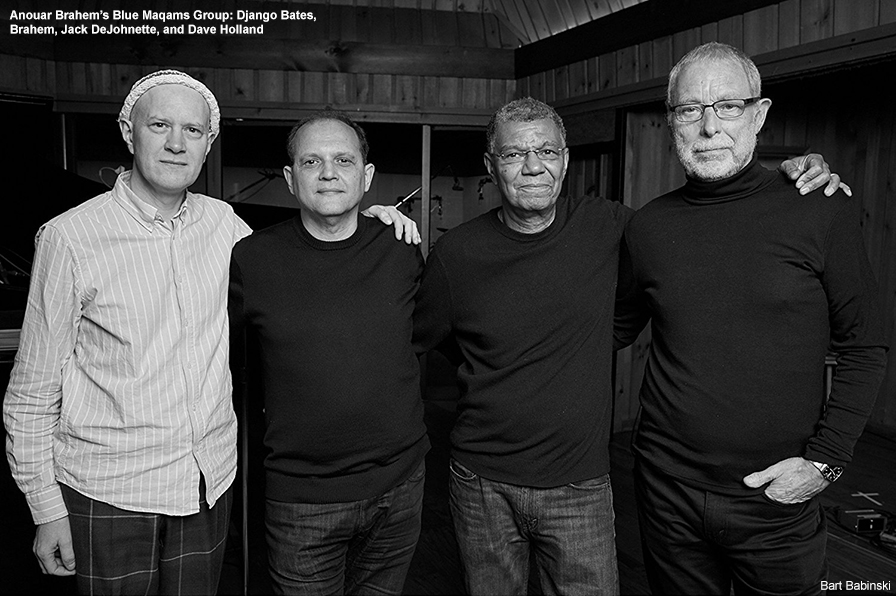

Uncompromising, eclectic and seeking are three words that define Django Bates’ career. The British jazz composer and multi-instrumentalist is responsible for a large body of expansive and influential compositions and performances, both as a solo artist and as a member of groups such as Loose Tubes, Dudu Pukwana’s Zila, Ken Stubbs’ First House, Anouar Brahem’s Blue Maqams band, and Bill Bruford’s Earthworks. His piano, keyboard and tenor horn work have also graced recordings by the likes of Harry Beckett, Christy Doran, Sidsel Endresen, Hank Roberts, and Tim Whitehead.

Bates is magnetically attracted to creating and instigating music that’s challenging and unpredictable. His journey as part of Loose Tubes, a British jazz big band active between 1984 and 1990, was emblematic of his early career and served as a launch pad for him and colleagues such as Iain Ballamy, Julian Argüelles, Steve Argüelles, Martin France, and Chris Batchelor. The group was frequently referred to—both seriously and sardonically—as an anarcho-syndicalist ensemble. It averaged 21 musicians in any given lineup, none of whom was the leader. While it was functionally and organizationally challenging, Loose Tubes made exhilarating music that turned the British jazz scene on its head during its seven-year run. In 2014, it reformed to celebrate its 30th anniversary with a series of concerts, including performances of newly-commissioned works.

In parallel with Loose Tubes’ existence, Bates began performing and recording with Bill Bruford’s Earthworks in 1986. The group, which initially also included Iain Ballamy and Mick Hutton, filtered Bruford’s interest in electronic percussion, his jazz-rock and art-rock history, and Bates’ and Ballamy’s diverse compositional bents, into a hybrid sound. Earthworks toured the world and recorded several albums before the lineup parted ways in 1993.

Soon after, Bates’ solo career took flight. He released a trilogy of albums for the JMT label in the ‘90s including Summer Fruits (and Unrest) and Winter Truce (and Homes Blaze), both of which featured his 19-piece large ensemble Delightful Precipice, and his quartet Human Chain. The albums expanded on the eclecticism of Loose Tubes, with mercurial, unconventional and sometimes engagingly zany works. A solo piano recording titled Autumn Fires (and Green Shoots) also emerged during this period. The three albums introduced Bates to a global audience, establishing him as one of Europe’s preeminent jazz visionaries.

Bates eventually established his own Lost Marble label. Its first release was 2004’s You Live and Learn...(Apparently), which he considers a career apex. The conceptual album contrasts choosing to benefit from history with the perils of ignoring it. In addition to Human Chain, it features a string quartet, vocalists, and explores instrumental and song forms.

In 2005, Bates was appointed Professor of Rhythmic Music at the Rhythmic Music Conservatory (RMC) in Copenhagen. His work as a jazz educator there led to his next Lost Marble release, 2008’s Spring Is Here (Shall We Dance?). The album was recorded with Stormchaser, a 19-piece group comprised of students that wished to explore his distinctive compositional and rhythmic structures. It was one of his most ambitious efforts to date, incorporating the school’s choir and a variety of experimental vocal approaches.

Stormchaser included bassist Petter Eldh, who went on to play a significant role in Bates’ subsequent albums with his trio Belovèd, also featuring drummer Peter Bruun, another RMC student. The group initially came into existence to explore Bates’ longstanding interest in the music of Charlie Parker, as well as to explore the possibilities of piano after a career largely spent in front of electric and electronic keyboards. The band offered audiences a mix of interpretations of Parker’s work, as well as Parker-inspired originals on their two Lost Marble recordings, 2009’s Belovèd Bird and 2012’s Confirmation.

Bates’ career trajectory further evolved in 2016 when ECM’s Manfred Eicher took notice of Belovèd’s output. The group’s third album, The Study of Touch, was released on the label in 2017, and found it shifting nearly entirely to original Bates repertoire, with the exception of Parker’s “Passport.” As part of the ECM stable, 2016 also saw Bates join oud master Anouar Brahem's Blue Maqams project in 2016, which included Jack DeJohnette and Dave Holland. Brahem felt the quieter, introspective side of Bates’ approach had potential to create intriguing musical conversations between the oud and piano.

In 2017, Bates raised eyebrows again by releasing the Saluting Sgt. Pepper album on Edition Records. Together with The Frankfurt Radio Big Band, he reimagined the classic Beatles album to commemorate its 50th anniversary. With a career and persona resolutely focused on rejecting commercial instincts, it seemed like the last thing he’d ever do—which is precisely why he did it.

Bates spoke to Innerviews for several hours, exploring the intersections between his three most recent recordings, as well as providing an overview of his storied history going back to his first album made with Dudu Pukwana. His perspective as an educator is also examined, including his current role as a Professor of Jazz at the Bern University of the Arts.

Your last three recording projects, The Study of Touch, Saluting Sgt. Pepper and Anouar Brahem‘s Blue Maqams were all released within a few months of one another. What combined picture do you feel they paint of who you are as a musician?

It was very pleasing that they all came out around the same time. But for those whose jobs it is to try and get attention for those albums, it caused confusion. So, I’ve done that once and I think next time, I might not do it that way again. As far as a statement goes, it’s that I don’t want to be pinned down. These three albums all reflect things that are close to me. They may have all arrived at the same time, but that wasn’t something I planned. It just happened like that.

Saluting Sgt. Pepper was planned a long time in advance because it involved all these big bands performing in different places. Halfway through that project, I bumped into Manfred Eicher and discussed the possibility of recording the Belovèd trio. A few weeks after we made the Belovèd ECM album, Anouar visited Manfred to discuss his next project. Anouar was searching for a new piano player, so Manfred said “Have a listen to these musicians.” He included my new recordings in his list. I got the call and said yes. I also felt it made real sense for my trio album and Anouar’s album to come out at the same time. They’d attract very different audiences and perhaps crossover between a few people.

Trace the evolution of the Belovèd trio from its inception to The Study of Touch.

We’ll have to go back to the very beginning, when I first started doing gigs in a jazz club at age 19 in 1979. The piano there was terrible. The venue was in an old wharf building on the River Thames run by Johnny Edgecombe. I thought “The piano is always going to be terrible. I need to get an alternative.” So, I got into keyboards very early on. I was lucky enough to get a Prophet-5, which is a very creative, personal kind of keyboard. It led me in a good direction with its sounds. In bands like Loose Tubes and Earthworks, I was always playing keyboards.

In 2005, I started working at the Rhythmic Music Conservatory in Copenhagen. Every time I opened a door, I was confronted by a grand piano that was sitting there looking at me. The pianos were always asking the question “Why have you neglected me for so long?” So, I started playing more piano.

One day, I was walking down a corridor of that school and heard an ensemble with a drummer and bass player and thought “Wow, what a very special sound they have together.” I had promised myself I would never have my own trio because there have been so many I really like including Bill Evans, Keith Jarrett, Brad Mehldau, and The Bad Plus that all did it so well. But then I heard Petter Eldh on bass and he had a punk mentality with the finesse and sophistication of jazz. The drummer, Peter Bruun, had a very intense, delicate approach who was also engaged in a lot of open-minded listening and responding. I thought I could put a piano with those two and it would be really exciting. I could tell the piano wouldn’t be drowned out. This is often the case. You’ll have cymbals crashing away, eating up all the piano frequencies. So, we arranged to meet up and play. I had no material for a trio, so we got into the room and experimented. We also focused on how we’d set up the three of us in a physical space, without any consideration for the audience. We tried many different approaches until we figured out a way for us to all hear and see each other.

We did things early on like say “Let’s play really quietly for as long as possible. Now, let’s play as fast as we possibly can for as long as we can sustain it.” They were very simple games we’d play. After about a year of meeting up and doing this, I was invited to present something celebrating the life of Charlie Parker for a concert in Copenhagen. I quickly arranged a few of my favorite Parker pieces and went into rehearsal with the trio. It was a very successful experiment. It was so easy to learn music having covered everything we did before. When we shifted to working with pages of written, organized notes, we found that our sound, phrasing and dynamics were already taken care of.

We concentrated on the Parker stuff for a while, because it was just such good fun as a composer to use that work as the basis of building the story, escaping from say “Donna Lee” and coming back into it from a very unexpected corner. Then I threw one of my own pieces into the repertoire one day and thought it was interesting to see how the Parker stuff and my stuff spoke to each other. At the heart of what I do as a composer, there must be Parker in everything, because his were among the first sounds I heard growing up. I gradually brought more and more of my own material into the gigs. We did a gig at the Bonn Jazz Festival when I suddenly felt “Let’s just play all my own stuff and maybe one Parker piece.” I just felt like it was time to take the performances back to that.

Describe how the principles of the Parker explorations extended into your original material for the trio.

With the language of bebop, you play a note and then you play around with it. Then you move on to another note. It’s interesting because of the interval or because of how you stepped away from the first note. These aren’t rules, but they’re part of the acquired language or ornamentation of the form. Once you’re inside it, it’s just such a beautiful language. It’s like learning to write with nice handwriting. It becomes part of your character, but it’s also a learned style. Everyone has the same letter form, but on top of that, you build your own personality into it somehow. It just happens naturally. So, on a tune like “We Are Not Lost, We Are Simply Finding Our Way,” the bass just uses two pitches—giving a minor seventh interval—and everything is built above that. That’s kind of the sound of the blues or bebop. You’ll really hear that if you listen to someone like Elmo Hope, whose left hand is just playing that minor 7th interval, moving it around or adjusting it. To some degree, Thelonious Monk did that too.

On a ballad like “Little Petherick,” it would be harder to find where the connection to Parker is. But I think there is one. It’s a love of melody. If I think about the first time I recorded that piece, it had sampled bird song coming in and out of it. So, there’s Parker in another way—bird song. [laughs]

Expand on creating “We Are Not Lost, We Are Simply Finding Our Way,” which is infused with many intriguing changes and micro-constructs.

That one started with me thinking “If I write a bass line that is quite ambiguous about where the pulse is and uses just two pitches, how can I turn that into a line we can all memorize?” So, I experimented with how long a line could be and still be memorizable by the musicians. I wanted the audience to think that it was never-ending—that it would just go on and on. They wouldn’t know what was coming next because they’re not reading the music. So, I wanted to create a feeling of surprise. It’s the way I like to do it. I was thinking “How wonderful it would be to have them experience a transition when they don’t expect it.” It almost magically becomes something else.

While I was experimenting, I tried various things with it. Some of them were too theoretical, not very organized or beautiful, yet not very meaningful. Those are reasons I might abandon certain directions. Then I found that something quite bluesy worked for that piece, with the top line going along with this ambiguous, hidden pulse that’s in the left hand. It adds to the question mark that’s hanging there for the listener, who’s asking “Where are they? What are they doing?”

A way to think about my writing process is to imagine you’re visiting a forest. It’s very beautiful. The trees are kind of interlocking and it all makes sense. But you can’t put a grid over it and say “I get it. It forms a square.” [laughs] A forest is tons of stuff beautifully locked together. That’s what I’m trying to create.

Let’s use an easier example so I can explain this further. The Study of Touch opens with “Sadness All the Way Down.” It came from a time when I went for a walk with a pencil and paper. I wanted to write some of my own music and start that writing process in a different way. I decided on the simple idea of starting at the very top of the piano and working my way to the very bottom—sadness all the way down the piano. Now, that can be done in an awful and banal way. But there’s another way you can do it which is beautiful. I might have tried to come down chromatically and discovered that didn’t work. So, I came up with a phrase at the top and repeated that phrase from different opening points as I went down and built an ever-changing harmonic picture around that.

Once I was given a chance to record the trio with Manfred, I decided to write another piece titled “Happiness All the Way Up.” [laughs] It closes the album. Now, that also could have been very banal. Even to have that title after the “Sadness” one could be considered banal. But I think banal as a starting point is okay for me. [laughs] It’s about the detail you put in around it. So, with “Happiness,” I didn’t just simply reverse the notes. I emailed Petter Eldh and said “Can you tell me the very highest note on the bass? I want to use that in a piece.” He didn’t get back to me, so I just kept writing. At a certain point, I arrived at this incredibly-high G-flat for the bass. I thought “Well, we’ll just see what happens.” I emailed him the part and he replied saying “Man, that’s incredible. If I go to the bridge and slightly over, I can just barely get that note.” I really love these kinds of coincidences. It’s almost like it was meant to be. It’s a confirmation of “Yeah, you’re doing the right thing.” It’s about organically going for it and seeing where things take you.

How did Eicher influence the recording of The Study of Touch?

His main influence was that he invited me to do a trio album at that point. I had a certain amount of material of mine for the trio, but I needed at least two-or-three new pieces for an album, because I felt we were going on a new adventure here. So, I had to make those happen. He also influenced the recording just by sitting there and listening to us as we played. I’ve done a lot of recordings in which it’s just the musicians in the studio and I’m listening and judging what we’re doing together. But to have someone else there who isn’t playing, but is an active listener, can make a whole lot of difference—especially when they have such a broad palette and so much experience. The process of recording was almost like playing a gig. That became part of the creative process. We went in there very well-prepared and with a very clear idea of the tunes. I think if musicians went into a session with Manfred and weren’t that organized that perhaps you might get a different kind of involvement.

What made you want to pursue the Saluting Sgt. Pepper project?

It’s very simple. I was asked to do it. Now, that might tell you that if anybody asks me to do something, there’s a chance I might do it. [laughs] The weirder and more unlikely the idea, the greater the chance I might give it a try. So, it was Christmas 2015 and the musical director of the Hessischer Rundfunk Big Band said “Would you be interested in arranging Sgt. Pepper's for us to commemorate its 50th anniversary?” I definitely remember saying previously that I would never arrange anything by The Beatles because everything had already been done with great expertise and a lot of input from George Martin. But as soon as the question was asked for real, the situation changed for me. I love that I’m very excited by such moments. My brain went through this thing I can’t control. It went through each track and came up with an angle for it that would make it fascinating for me. At the end of that instantaneous process, I thought “Yeah, go on. Why not? Let’s try it.”

I also went into it thinking, more than I usually would, about what kind of people would be annoyed by the project and who would like it. I thought “People who usually like me won’t like it because they won’t understand why I would go near that kind of music. And people that really like the original version won’t like it because it’s not the original.” I have to say, at the end of the day, I just decided to do it in a way that made sense for me. We played it for a week at Ronnie Scott’s club, two shows a night. It was pretty full on and the audiences got it. Everybody I spoke to made the connection. Half of them said “I was really of two minds about coming to this gig. I was worried it would ruin my love of the album, but what you did was give it a huge pile of respect, plus some development and new perspectives.”

I should mention in addition to the Sgt. Pepper’s material, we did “Strawberry Fields Forever,” “All You Need is Love” and “Penny Lane” because they were part of the package of songs that should have been on the original album.

When I first heard you were doing Sgt. Pepper’s, I thought it might have been a radical reinvention of the album. As it turned out, you were a little more gentle with it as you infused jazz harmony and changes into it. It remains recognizable. Tell me about the philosophy you adhered to.

Yeah, I made the decision to keep something at the core of it that was very authentic to the original, which involved the voices and drums. A lot of the time, the bass lines are true to the original. That did still leave a lot of room for coloration, texture and new rhythmic things. Essentially, it was like having a black-and-white drawing of the album and then filling it in with watercolors and oils.

I played each track using headphones, slowed it down and looped parts of it. I transcribed every piece in my own way. I know you can buy it all in a book, but I don’t get very much from looking through someone else’s transcription. I had to hear it all for myself, because the album has so many muddy layers of overdubs. Some of it is just bounce dust, but still contributes something very important and might make me think “I’ve got to have that in here and have someone represent that sound.”

I would pick out what I thought was essential about each song and then see what was left around it. I really enjoyed working on “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds.” Whatever the words did, the stuff behind them remained the same, whether it was a piano comp or a pretty static drum groove. But I was able to ask “What do marmalade skies sound like to me? What would that sound like in my head?” I looked out into the sky and suddenly it was like marmalade and created a sound that goes with that. For “the girl with kaleidoscope eyes,” I got all those instruments to swirl around in big circles.

Describe how the chemistry that informed Anouar Brahem’s Blue Maqams recording session evolved.

Anouar had chosen Jack DeJohnette and Dave Holland for it and was looking for a piano player. It’s a very different album from his previous ones. He was starting from a position of wanting more space. I was lucky he got to hear The Study of Touch. It’s a good example of the fact that I like to play really quietly. I enjoy the sound a piano makes when it’s just touched.

After Anouar heard it, he came to Bern and we talked a little bit. Then we played together for a day. After a few hours he said “Yeah, I think we’ve done enough.” I took that as a good sign. We could have been struggling around for hours trying to find the combination that worked. When we first started playing, I wasn’t sure how I could blend with the oud having never played with that instrument before. There are also differences in tuning, but there are ways to deal with that. What was important was understanding the areas he was playing in and where the space around that was. He played through all the material and it was quite subtle, yet very detailed in terms of what he asked for from me. He said things like “When you play this phrase, just slow down a little bit here in the middle and then drift off there.” He also said “Can you swing this phrase slightly less?” We explored details and places where there was room for me to not just be within the original mode, but to have the ability to introduce other harmonies in the way that jazz players do all the time—and then come back to the mode. I could see there was going to be room to be creative.

The next thing was turning up in New York and going to the studio to meet Jack and Dave. We were in a very nice room making this music happen. I think Anouar quite likes the music to not be toured a lot in advance of recording. He likes musicians to go in there and discover things in the studio. I’ve been on another record like that, which was Sidsel Endresen's So I Write, with Nils Petter Molvaer. We had never done a gig when we did that album and I didn’t really know Nils Petter, previously. So, there’s a solo on there I’m playing in which I figure out how I fit in for the first time as we improvise and find out who we are. These are the kinds of things that get onto ECM albums, which probably don’t on my other albums, because I work in a different way. Both approaches are special and different. The ECM idea of documenting the moment of discovery is quite exciting.

What was it like for you to work with such an extraordinary and historic rhythm section?

When I was there working with them, I didn’t think of it in those terms, but when I was on the plane to the sessions, I was very excited. I was thinking about Kenny Wheeler’s Gnu High, which was very important to me early on. It has Dave and Jack on it. That album is many years old and I realized they’re different people now. I also thought about Miles Davis and the work they did with him. But once in the studio and the tune begins, it’s always the same process of keeping your ears alert and being sensitive to your own role in the music. I was careful not to just show what I can do because I was thinking about what these guys did in the past. No. The question is “What does the music need right now?” Dave and Jack are both very humble and supportive guys who would always be considering that first.

Did the music evolve further on tour?

The tour was very easy going. It didn’t take long to for it to sound good because the music is very well-balanced internally. There was no struggle to make the music project out into the audience. It was just a very natural thing and the music grew, but didn’t change drastically. It just melted together even more. During the last gig, there was a bass and drums part when Dave and Jack went into something I recognized from Miles Davis’ Live Evil. It was just for a moment with Jack doing a funky fast hi-hat thing. It was great to see them referring to that and pulling it off in a way that worked within the space that was in the piece.

It was a really pleasurable experience and we’ve played some beautiful rooms, old and new. The 2018 tour had places like the Elbphilharmonie and Philharmonie de Paris which were rooms designed for a lot of people to be listening. The audience was close to the band. In the old days, venues were set up as rows of chairs stretching out into the distance. Some venues had very beautiful pianos which were such a joy and privilege to play.

Did Blue Maqams have an impact on your own compositional leanings?

My answer isn’t very profound. Paul Motian once said “The trouble with jazz musicians being interviewed is that every time they’re asked a question they think they must surely have an answer to the question. Even when they don’t.” So, that’s the background to this answer. [laughs]

I’m really happy with how everything turned out. But beyond that, I was interested in what the difference was between that project and what I do on my own. I can see that it goes all the way back to my upbringing in music, which addressed what the role of art was in society, including what was good and what was perceived as not good.

I grew up in a really interesting family. I’m really grateful for the experiences I had. The wide range of music that was played for me as a child was at the eccentric end of each genre. I was hearing the best of Gypsy music from Romania, South African music, Kwela, and American jazz. There was no television at home because that was judged to be rubbish. Pop music was hardly spoken about because it wasn’t art, but money-making stuff. For my parents, art and money were not connected. Art was supposed to be something that wasn’t too easy or too pleasing. So, I had an interesting set of guidelines growing up which gradually informed my own guidelines later in life.

I realized when doing the Anouar project and realizing that people love it, that my own music is deliberately confrontational. As I said earlier, I’m picturing myself in the audience as I’m writing my music. So, that is self-consciousness right there. When I’m writing, it takes place in sort of a dream state. It becomes complex and detailed as a reflection of the joy in the craft, and then I hope it can be played in a way close to what I intended. That’s a very different approach to Anouar. He doesn’t likely have those kinds of guidelines. What he does is more organic and I can imagine it takes a long time. For Anouar, it’s not a construct, it’s a flow. It’s able to fly out into a very big audience and not push them into a zone like my music that says things like “You think you’re here? Well, now I’m taking you somewhere else. Are you surprised about that? Are you happy? Isn’t that weird?” [laughs] With Anouar’s gigs, some audience members said they fell into a trance. I really feel I learned more about what I do and what choices I have when I’m writing through what Anouar does.

Tell me about the decision to reform Loose Tubes in 2014.

I was very happy that we managed to get everybody back together. My manager Jeremy Farnell, who wasn’t involved when the band originally existed, was very helpful in organizing it. He wasn’t emotionally enmeshed in it and made very valuable suggestions on how to make it all work. The band is a totally unique group of really amazing characters, who are all very funny. They’re all individuals. It’s 21 people and they all take up a lot of space, emotionally-speaking. It’s why the band is what it was, but it also meant it was bloody hard to make the reunion happen.

A couple of years before the reunion, there was an event in England called Jazz Britannia, which was on television. It was a celebration of British jazz going back to the era of Loose Tubes. It was focusing on a so-called jazz revival, but for various political reasons, Loose Tubes was completely overlooked. I suppose it had to do with the fact that while the band was originally around, a lot of people loved us, but we also pissed off a lot of people in the promotional end of things. We didn’t ever play ball with them. We were quite disrespectful and even childish at times. Today, I see the new generation of musicians who are really skilled at the political side of being a musician. I would say there’s too much of that now and not enough focus on the essence of art.

So, after Jazz Britannia, I thought “This can’t be left like that. We have to do something. What can we do?” This relates to the fact that a couple of years before that, Ashley Slater, the trombonist in Loose Tubes, called me and said “Hey, listen. There are six reels of tape from the last live gig Loose Tubes did at Ronnie Scott’s in my old apartment. If you want them, you need to get them now.” So, I drove to the apartment and didn’t even know who lived there. I knocked on the door and said “Hi, I think there are some tapes here.” [laughs] Ashley said they were in a cupboard above a door. So, this girl comes out and says “I don’t think there is a cupboard above the door.” She goes and looks around and then said “Wait, there’s a handle above a door.” We went and had a look, opened the handle, and all of these old socks fell out. And behind the socks, there were these six reels of two-inch tape. [laughs] I said “Okay, I’ll take those.” I did and we had to do all the usual stuff of baking and digitizing them. I listened back in the studio as soon as this music could be heard and realized it was a fantastic recording in terms of the vibe and quality of the sound. The rest of the band agreed. It captured the essence of Ronnie Scott’s as it used to be, too.

So, we put that all together by 2014 and the first two albums of those recordings were released, titled Dancing on Frith Street and Säd Afrika. I thought “Now that this material is out and is being so well received, it would be nice to see if we can actually get everyone together on a stage again.” My manager quickly realized no-one was going to be interested in putting this on unless there was some new music involved. Presenters like to have creative involvement and see themselves as the commissioners of something new. So, that’s what we did. We had some new pieces commissioned, got together, did a week at Ronnie Scott’s, and it was the same as it ever was. It was full-on and exhausting. No matter where you were, there was always another anecdote to hear and you’d get drawn in.

Reflect on the legacy of Loose Tubes and how its musicians went on to influence the direction of the British and European jazz scenes.

I think Loose Tubes gave everybody a huge boost of confidence at a very important time in their progression as a musician. For myself, before Loose Tubes, I had been playing with Dudu Pukwana, going around these little jazz clubs and festivals. I was in my twenties and thought “If I play really well all the time, eventually I’ll be noticed and I can bring my own band through these clubs.” I quickly realized that no-one was noticing me. They were digging the gig with Dudu, but me giving cassettes to the promoters was having no impact at all. I couldn’t see how I could make the next step in that context.

When we formed Loose Tubes in London, we would do pub gigs which went down shockingly well. People would get up on the tables and dance. So, it was clearly something with the ability to make a big impact. There was big power in having 21 people in a band. It was a huge force. Eventually, Colin Lazzerini, who administered the band, got us a gig at Ronnie Scott’s. Ronnie had heard the band and loved it. He was very supportive.

The first night we played at Ronnie’s, as we arrived at the gig, we started playing out on the street before soundcheck. Everyone was so exuberant and desperate to play. What happened, was everyone on the street knew something big was going to happen inside. At the end of that show, we took the band and the audience back out onto the street, and then went back into the club. The press were there and gave us fantastic reviews of that first show. And it served as the launchpad for a whole bunch of careers. That particular day was all about making a mark. It was no longer possible to ignore those players anymore from that point forward. So, there can be luck and rewards for putting a huge amount of energy into a gig like that.

How do you look back at the first Loose Tubes studio albums—the self-titled 1985 release and Delightful Precipice from 1986?

We were all inexperienced in making albums. It’s a huge art in and of itself and no-one really knows how to get it right, except perhaps Donald Fagen who spent years making The Nightfly. Maybe he knew how to get everything exactly as he needed it. But at our young ages, with that lack of experience, we were just lucky to get into studios and document this stuff at all. I think there are some great moments on the Delightful Precipice album. The first album is probably a little bit too neat and tidy compared to what the band was really like. But people’s experience of an album as a listener has nothing to do with the experience of the people who actually played and recorded the thing. If listeners have good memories of the recordings and got pleasure from them, that’s good enough. They’ve done their job.

We haven’t reissued those albums because there’s a question of who owns the master tapes and where they are. At some point it was rumored that the person who had the tapes sold them to someone in England. When I heard what was sold, it was out of phase. Instead, I felt the previously-unreleased live gigs were something much easier to do. There was no record company involved. I own the tapes. It’s unusual for a musician to own three albums worth of tapes. There’s a pragmatic decision still waiting to be made about the first two albums.

How did Teo Macero get involved as producer of Loose Tube’s third studio album, 1988’s Open Letter?

That album was on E.G. Records and the connection to it was Bill Bruford. Iain Ballamy and I were playing with Bill at that time. E.G. came out to see Loose Tubes perform and for some reason they thought “Yeah, let’s do an album,” even though stylistically, it wasn’t an E.G.-type of project. We had some meetings and ridiculous suggestions were made about producers. The band had 21 people and we had 21 ideas. If you wanted to stop the meeting and have a cup of tea, you’d even have to have a vote on that, which would take 20 minutes of discussion. [laughs] That’s the sort of band it was. So, Teo was a suggestion that was made. He had made incredible, memorable, fantastic albums. I don’t think he had worked with a European band before, though.

One of my favorite memories of Teo is watching him play the music back on the enormous studio monitors at Angel Studios. I mean, it was so loud he was cutting out these enormous cones. Another time, someone in the band started being rude about Ronald Reagan. Everybody assumed everyone felt exactly the way they did about politics, not realizing American politics were just as complicated as ours. Teo got upset and started giving us a lecture saying “Reagan is the best goddamn thing that has ever happened to America!” [laughs] There was stunned silence following that.

Teo made some nice suggestions. He said things like “You should repeat that phrase. Don’t play that once and then just move on to the next thing. It’s a beautiful part. Place it twice.” That seems very simple, but it was important. Teo made Charles Mingus’ Mingus Ah Um. I grew up with that album and am very attached to it. Now, I can listen back to it and realize how important Teo’s involvement was and how much he cut out and changed in the arrangements. The original, unedited versions are now available, and I have to say the edited, original album is a million times better. He would say things like “There’s not much happening here in the first two choruses, let’s cut them out and throw them in the bin. Let’s go straight to the third chorus where it’s just full on.” It was almost like making a pop album in a way, with everything high energy.

Loose Tubes had never worked with a producer before. We didn’t know how that worked, but we somehow got a good result between all of us on the album. It sounds nice. When I got to work with Stefan Winter some years later, I was still not in the right frame of mind to have a producer in the same room with me. Now, I realize it can be fine and really helpful. They can be there like an audience as I said when discussing Manfred Eicher. Until then, I always assumed that having a producer meant you had to argue. Stefan and I had lots of arguments, but in the end I got three very nice albums out of working with him.

What did your experience with Loose Tubes teach you about the necessity of band leadership and management?

I have to say that I wasn’t the band leader, even though some perceived me to be. It was an anarchic collective because there wasn’t anyone in charge. I did learn a lot, though. I am really a very quiet person, but when I was challenged in the band on anything musical, I had a terrible temper. It’s crazy to think back and see how different a person I was. I also never announced anything form the stage. It’s weird that this silent, grumpy kid behind a keyboard was perceived as the leader of the band. Perhaps that’s because I was at the front, took a lot of solos and wrote a lot of the music. The latter is probably the major part of the perception. I brought the first piece I wrote for the band to it when it was a workshop group for Graham Collier. He was playing the music of his contemporaries, but by the second week, I came with my own piece because I saw an enormous opportunity there.

I also found it very frustrating to watch the set list emerge before a gig. It would happen a half-hour before the show. A few people would start throwing it together. I don’t know why I didn’t just say “That isn’t how you do it. Let me do it.” So, I would watch this kind of chaotic situation of putting two tunes together that were in the same tempo and key. I’d think “Why are we doing that?” So, I began to form very strong opinions, but I didn’t act on them until later. It was all part of laying the groundwork for the future.

When Loose Tubes finally collapsed, I almost immediately started another band called Delightful Precipice and experimented with different ways of doing things. We’d rehearse music in a very precise way and tried to be as efficient as possible. We got great results. We put set lists together in a way that gave gigs a journey, shape and a curve. I began enjoying presenting music to the audience and talking to them. Loose Tubes, as an anarchic collective, couldn’t have had that level of discipline. But it was a good place to be in and gave me a lot to think about in terms of how things could be done differently later on in life.

In parallel with Loose Tubes, you also had the smaller ensemble Human Chain. Tell me about how that group emerged.

Human Chain started as a band called Humans, formed simply from the need to have a small group. I changed the lineup many times and decided to call it Human Chain because the band became a chain of characters and experiments. For a while, it was a partnership between me and Steve Argüelles. A lot of the time, the band was just an idea and wasn’t doing much rehearsing or gigging. If I formed that band now and used its last version, I think I would have a clear idea of what it could be now. It would be one thing, rather than a group that experimented constantly. When the band played the Montreal Jazz Festival in 1993, it was a very powerful experience. I bring it up because I remember performing outdoors to a lot of people. We did our out there version of “New York, New York” in front of all of them and at the end of it, it was dead quiet. Everyone was stunned speechless. Just one single person yelled out “Yeah!” [laughs] And even that may have been nothing more than a sarcastic response. But I didn’t care. I thought “That’s the idea of the piece. It’s meant to be quite shocking.”

You mentioned the trilogy of albums for JMT in the ‘90s, encompassing Summer Fruits (and Unrest), Autumn Fires (and Green Shoots), and Winter Truce (and Homes Blaze). How do you look back at that fruitful period of your career?

Fruitful is the right word. It was an interesting period for me in all ways. I was experiencing a kind of condition that would have the word “manic” as part of it somewhere. I was flying with a mad kind of energy and a lot of the band were as well. Delightful Precipice, which appeared on two of those JMT albums, as well as Human Chain, which was also a part of Delightful Precipice, were groups with which anything seemed possible, musically. It seemed like a time when I could arrange “New York, New York” one night and then rapidly go on to play it with a big band in Copenhagen the next night and have an incredibly warm response to something which was actually pretty out there in terms of arrangement. We had relatively a lot of gigs at the time. I look back and think “How the hell was that possible?” Sometimes, I think “Okay, having Polygram behind you does make a difference in the traditional way we always thought it was meant to.” So, I did experience what it was like to have the support of a record company. We did a residency at the Montreal Jazz Festival, which was a long way to travel. That was all supported by that infrastructure in some way.

Musically, the JMT albums weren’t very planned in a conventional sense. Typically, someone might go “Okay, I have a three-album deal. What should I do on this journey? How shall I present the music? How should I tell this story?” That’s why on the first album Summer Fruits (and Unrest), you have Human Chain and Delightful Precipice on it. I have a big band and a small band both playing on it. I think that wasn’t a good idea, because I confused the audience. Next, I did Autumn Fires (and Green Shoots), a solo piano album. I’m not sure how that fits in, but it was nice to do.

For the third album, Winter Truce (and Homes Blaze), I had the big band and small band again. It would have made more sense to have presented the big band first on its own album and the small band on its own album later. But to be honest, I never had quite enough material. When I first got the call from Stefan Winter and he said “Let’s do an album,” I looked at the material I had and the reason I called it Summer Fruits is because I felt very summery, optimistic and fruitful. I felt I had some material that, if it didn't get used pretty soon, would go off. So, I put it all together—four big band pieces and four small band pieces. There’s no point in regretting it. It was an album no-one else would have made. I’m grateful to have done it and some of the juxtapositions of the two bands made for some really special sounds and combinations. Also, I brought my friend Andrew Murdock from America to record and produce it. He had never recorded a big band before, but I loved his work and energy. With Stefan, he pretended he had in fact recorded a big band before and came and gave it a go. [laughs] That was a part of the story. I really like the sound of that album.

You’ve enjoyed a multi-decade working relationship and friendship with Iain Ballamy. What makes him a unique presence for you across both realms?

The first thing that springs to mind is that the ongoing conversation between us is just so rewarding and entertaining. He’s a very empathetic person, a good talker and a good listener. We’ve had some wonderful musical experiences of equal importance. I don’t see Iain that often. He lives in England and I’m in Switzerland. But I’ll text him with two words from something weird he said at a Bruford gig in 1987 and he’ll know what I’m referring to and send the rest of the sentence back. It’s very amusing and good to know someone for a long time and have those shared memories.

In terms of Iain performing my music, the thing that comes to mind is the piece “Little Petherick.” He played very quietly and beautifully on it. I wanted to play it with some of my students, so I transcribed it. It changes octaves at one point, because it’s off the range of the sax. As I was transcribing it, I was thinking “This is royal. Every note is just like velvet. The way he moves the melody through the whole saxophone range, and the different mood he gives to each phrase is wonderful.” He really excelled on that.

What are your thoughts about your tenure in Bill Bruford’s Earthworks between 1987 and 1992?

Earthworks happened because Bill called Iain one day at his parents’ home and said “Hi, my name’s Bill Bruford. I don’t think you know me, but I happen to live ‘round the corner from you, two miles down the road in Guildford. I play the drums. I used to play in a band called Yes.” Iain said “I haven’t heard of them.” Iain’s much younger than even I am. So, Bill said “What about King Crimson, perhaps you know them?” Iain said “No, I’ve never heard of that band either.” Bill responded “That doesn’t matter. I heard about you on a jazz broadcast the other night. I thought it might be good to get together and play a bit, because we live nearby.” Iain responded “Yeah, great.”

So, Iain went and they played together a bit. Bill said “Look, I’ve got these electronic drums that play notes and chords.” He showed Iain and made them go "blong" and "plong." [laughs] He wanted to see if anything was possible with them. Iain suggested getting together with me and Mick Hutton. We went to my parents’ house and played together a little. Bill said “I’ve got these notes on the drums” and we very quickly built a tune around them and grooved around. We had some fun. After a few hours of rehearsal, Bill said “I’ve been offered a gig in Japan in two months’ time. I don’t actually have a band at the moment. Are you interested?” [laughs] We all said “Yeah, let’s do that. It sounds amazing.”

Within two months, we got a whole set’s worth of material together. It’s incredible when things like that happen. You look back at the time scale later and think “Wow, that’s what was possible then.” All of the tunes were slightly different and had good titles. They had a unique flavor with the electronic drums. We played Japan and became a band. I had a great time hanging with Bill, Iain and Mick, and later Tim Harries. We toured and saw America. I learned what gigs are like in America at these rock venues. I also learned a different way of playing. Bill would say “When you’re doing your solos, you play like you’re in a small club, with as many notes as possible all the time. But this is a big place. You need to leave some space around the notes.” He called the thing he was looking for “stadium jazz.” [laughs] I don’t think we listened to him that much as far as improvisation went. It took years to really think about that and for it to sink in, but I think he was right.

Bill’s way of playing was very interesting, because it wasn’t like any other drummer I played with. His way of playing was never ambiguous or floating. It was very direct. It was like “We’re here now, bang!” That was quite refreshing. It jolted me out of the introverted jazz world and I think I played differently as a result of that experience—just like I played differently after working with Dudu Pukwana all those years before. Bill definitely had an impact on what I choose to play and when I choose to play it.

Describe the circumstances of your departure from Earthworks.

I recall writing a letter to Bill which said “I’ve had a really wonderful time, but I feel like I want to stop being in this band now.” I can’t remember whether or not I gave a reason for that. Loose Tubes had just ended. I was starting Delightful Precipice, which I thought could be like Loose Tubes, and Human Chain felt like it was taking off. I felt Earthworks had done its best. We’d reached a point where it felt like we probably weren’t going to do another studio album. Writing music for the band became a little less spontaneous and more hard work to find ideas. I may have also sensed from Bill that he was ready for a change. His enthusiasm for carrying around the electronic drumkit was diminishing. The stress of wondering whether or not it was going to work every night wasn’t appealing. We really didn’t know if it would sometimes.

My closing thoughts for Bill were “We’ve done this band. We’ve stretched the possibilities of two horns and electronic percussion. I hope you’re really proud that you took two snotty-nosed jazz kids around America and showed them a set of possibilities they wouldn’t have thought of or known otherwise.” I remember specifically saying “snotty-nosed.” [laughs] I think it’s because Bill was a sort of father figure for us. He was always the grown-up in the band—the sensible guy who had done things before. We were always the kids figuring out how things worked. That’s a true reflection of that experience.

Most people aren’t aware that you were part of the Rain Tree Crow sessions in 1989. Tell me about that experience.

The thing I remember most is getting the album and thinking “I’m not on here!” [laughs] I was surprised at that. We worked in a very nice studio called The Wool Hall in Bath. The vibe was very different from every other studio I had been in. During all my sessions, there was always a massive time and budgetary constraint. I got there and everything felt quite slowed down. They said “We’re thinking about having dinner. Are you interested?” I said “Yeah, that sounds good.” And a chef was there and brought some food out. I’m not saying it was a luxury thing, but it felt so different.

The band was asking me about the Loose Tubes albums. They’d ask “How long did it take you to make that record?” I’d respond “Three days. Two days in the studio and one day mixing.” They gasped and said “No way!” I asked how long they had been there working on their album. They said they’d been living there for months making it. We really were coming from completely different worlds.

I remember Mick Karn being there. He had played bassoon in the same school orchestra I was in. Richard Barbieri took me to a Hammond organ and said “I’d like you to try to play this part on this track—coming in from this part of the music to this other part.” I said “I don’t really know how to play Hammond. I’m not sure how to get this sound.” He said “Let me have a look for you” and got a really nice sound. I thought “You should play the transition because I can’t quite find my way in there.” They then played the section and it was a very beautiful, organic moment. I’m sure nothing was written down. Karn was very spontaneous. He played the bass but didn’t know the names of the notes or whether something was up or down. But I couldn’t find my place within all of that, either. I didn't recognize what I was hearing. I didn’t understand it.

Next, I tried to play the horn over the transition, but I don’t think I came up with the right thing. Looking back on it, I’d say it was one of those moments when I would have wished for a more pop side of my childhood to emerge, but it didn’t exist. I’m not saying Rain Tree Crow was pop, but they had a sensibility about working in which things weren’t written down in a typical way. They also had a slower way of working in which you don’t feel rushed and can experiment and play around a bit. I think if I did that session now, it would be completely different. Today, I would have said “I want to hear the transition. Okay, I want my part to go from the top of the of the piece and I’d love to also do something here.” I would know how to communicate that now. I would have figured out a way to contribute in a way that bound the two parts together. Back then, I was a little too much of a snotty-nosed jazz kid to do that.

Regardless of the fact that they didn’t use me on the final recording, it turned out to be a great album. They spent a lot of time on it. They had a concept that was quite improvisational and I liked that.

During the period in which Loose Tubes, Human Chain and Earthworks co-existed, you also found time to record two albums for ECM with First House between 1986 and 1990, led by Ken Stubbs, and featuring Mick Hutton and Martin France. Explore that project.

Ken seemingly appeared out of nowhere on the scene. He came down to London from Manchester. He knocked on the proverbial door and said “I’m a saxophone player from Manchester. Do you want to get together and play?” I think it was Evan Parker who recommended me to Ken. As I’ve said, at that time, everyone said yes to everything. There was a lot experimenting going on. I was playing this kind of jazz influenced by Keith Jarrett’s American and European groups, with a little bit of an English folkie vibe, and then here comes this alto sax player doing hardcore, but very personal jazz stuff.

Before you know it, Ken meets up with Parker, who helps him construct a letter to Manfred Eicher, and suddenly we’re whisked off to Rainbow Studios to make an album for ECM. When that happened, it really annoyed a lot of band leaders. They couldn’t figure out how this band suddenly ended up with ECM. Ken sidestepped all the norms and rules. I was very young and inexperienced, but I was suddenly in the most prestigious recording situation imaginable. I spoke to Manfred about it a while ago and said “Man, you have to remember I was so incredibly young back then.” He said, “Yes, so was I.” [laughs] It didn’t even occur to me to think about it in those terms. It was an early thing for everyone.

The music on the first album is very different to anything else I’d ever played before. By the time we got to the second one, I found it was more like the stuff I normally do. But the first album is a real one-off. I can still remember the tunes. We memorized everything, which was unusual. There were some very fast tempos. It was not quite tonal, so I really liked it. I saw Ken not that long ago and half-jokingly said “We should get back together for a reunion.” He didn’t rule it out completely, although he now lives in Australia.

You mentioned your work with Sidsel Endresen on her 1990 So I Write and 1992 Exile albums and associated performances were very impactful on you. Expand on that.

It was after the initial First House recording that the Sidsel album opportunity came along. Manfred heard me with Ken Stubbs and then had me in mind for Sidsel. It was a very different project and it’s interesting that he spotted another side of my playing. What happened is I came home from a rehearsal one day and there was an answering machine message waiting. This was back in the days of cassette tapes recording those messages. I heard a message from this Norwegian female voice saying “I’m a singer. I have a band and we’re planning to do some gigs. We wondered if you’d be interested.” As I’ve said several times, everyone was up for everything back then.

What was interesting is that after I heard five words of her speaking, I was completely entranced by her voice, manner and accent. She sounded very engaging, special, very quiet, and humble, but powerful as well. I just thought “I’ve got to do this. I don’t even know what it is. I’ve never heard of her before. I don’t know who’s in the band, but yeah.” [laughs] So, she sent me some cassettes of demos with her, Jon Christensen, Nils Petter Molvaer, and a different piano player. I was given the opportunity come in as the piano player for this beautiful music. At that point, the whole concept of singing and singers in the jazz world had made no impact on me at all. Perhaps that was my father’s influence. He didn’t like American jazz singing with lots of vibrato and theatrics. I heard a lot of Billie Holiday and Bessie Smith at home, but nothing else. I also hadn’t worked with any singers previously. I never thought I’d be in the song world, but I went to the rehearsal, we started playing, and everything was very quiet. I thought “It can’t be this quiet during performances, surely.” But each tune would start very quietly and then get quieter. I thought it wouldn’t work and it would be embarrassing and weird. So, we get to the first gig and the quieter we got, the more the audience was sucked into this miniature world of concentration. At that moment, I learned so much about a different extreme to the world of Loose Tubes, which involved bashing people over the head with a powerful sound.

The other thing that happened is I started thinking about words. Up to that point, though I had stumbled onto Bob Dylan, The Beatles, Stevie Wonder, and others, I realized I had never actually listened to lyrics. All I heard was the music. Then Sidsel started sending me sheets of white paper with a little box of text in the middle. She’d say “Can you come up with some music for this?” It was like Christmas morning for me when those sheets would arrive in the post. I’d open it up, read the first few lines, and an instant musical response would come into my head. I was very inspired by her and the band.

The album I released in 2004, You Live and Learn... (Apparently), included lyrics. It has a theme going through it about people learning or not learning. I wrote all the lyrics myself, which makes it quite personal. Songs are like a weird world for me. I lived and learned in terms of working on them, too. I put everything I could into that album. It included so many musicians, including a string quartet, extra brass, a choir, and even David Sanborn playing on “Life on Mars” as a reference to Bowie and saxophones. If I had to give someone a single album of my stuff, that’s the one. I like all of the albums I’ve done, but most of them have random moments during which things weren’t really thought through. But You Live and Learn… is one I can really stand behind.

Your parents have come up a few times in this conversation. Provide a snapshot of them.

I think of them as hippies before that was hip—probably before the word was invented. They went to India and hitchhiked across the bottom half of Australia in the late ‘50s. My sister was born in ’58 in Australia during that period when they were exploring open-minded, slightly mad behavior. They came back to London where I was born in 1960. My father had many jobs. At times he was a painter of paintings and it’s intriguing to me that he chose not to become an artist. I felt like he gave up on that and that’s a part of being an idealist to the point where you can’t operate in the artistic world because you struggle as you come up against reality. For visual artists, that means dealing with galleries and gallery owners. Being told what to paint and giving a huge percentage to the gallery wasn’t something he could get into, but I’m disappointed he didn’t go for it.

He then became a gardener for a long time, working in people’s private gardens, making them look incredibly beautiful. The truth is he couldn’t work for anybody else. If he was working with other gardeners under a head gardener, it would have all gone wrong immediately. He couldn’t take instructions.

My mom broke away from a pretty well-to-do family and hitched up with my father. He was a carpenter when he met her. She went off with him, but much later in life realized she had a passion for mathematics. She became a math teacher, went to Malawi and started a whole new life and relationship. That was the end of my parents as a couple.

So, that’s the main framework of my childhood. There was always lots of interesting music playing in the house. My father was the one who threw all the sounds in the space by playing records. He’d also record snippets from the radio and play the tape later. It might have five seconds of Schnittke and then five seconds of Jelly Roll Morton—just odd moments he caught and thought were interesting. He’d have these incredible tapes of sounds.

My mother’s influence, musically, was that she would cycle me to instrumental lessons in the snow after working a whole day of teaching. She’d wait outside the house until I finished. She also ensured I attended a school in which free music education was available. She was incredibly motivated as a parent who saw the musical potential of her son.

It surprises me that I was so obedient as a child, because obviously one is meant to rebel at a certain point. I did remember taking Steve Reich into the house and having my father say “No, no, this isn’t where it’s at.” [laughs] There were two-week periods during which I’d go minimal. At age 18, I had an influential teacher who would show me the recent classical end of music, including Reich, Charles Ives, Gavin Bryars, and Elliot Carter. And then I’d find myself going back to jazz and realizing I loved the improvised, dangerous, anarchic side of it. I also recall hearing Stevie Wonder’s Songs in the Key of Life when it came out and thinking it was like the first time I tasted sugar. It was absolutely incredible, wonderful, rich, rewarding music. I still feel that way about that album today.

Another thing is that there was a very anti-religious message at home. I was told not to go to religious lessons because at that time, those lessons wouldn’t be about all of the religions of the world. I don’t know if that was a great idea, because I never learned anything about the bible and so many lives were was informed by those stories. But my parents did have an understanding of morals. They told me I shouldn’t steal or lie.

How did your parents react to your musical direction as a jazz artist?

There was a certain point when I made it entirely my own and it was no longer a quest for approval—which playing music was for a long time. When I first started, I was playing stuff from my father’s record collection in the hope that he would be interested. Later on, I thought “Actually, I don’t need to do that. I can really enjoy making the music I want to make.” They were fine with that. They didn’t complain about my direction.

Your first major career experience was becoming part of Dudu Pukwana’s orbit in the early ‘80s. How did that opportunity come about?

This very much fits in with the discussion about my parents. My father had an album called In the Townships by Dudu Pukwana from 1974. I loved those tunes. They were very simple and powerful with screaming saxophones over the top of things and great, lusty singing.

Earlier, I mentioned the first gig I ever performed at was at a place run by Johnny Edgecombe on the River Thames in an old wharf. It was very romantic and seedy. It was the real thing—the sort of jazz club I read about in books. I’d play the first set with anyone I could find that understood jazz a little bit. Then another band would come on as the main act. We’d see them, watch and learn. People like John Taylor, Stan Tracey, Harry Beckett, and John Stevens would come through. After a few weeks of playing these shows, I realized they’re all playing their own tunes and not my dad’s record collection. I thought “I’ve got to do that, too.” So, I started writing. Those musicians were a big influence on that.

One night I played, the next band that came on was Dudu Pukwana. I thought this guy was based thousands of miles away, but there he was in the room playing this stuff. The audience was absolutely electrified. I was watching him thinking “When we play, it’s almost like we’re not in the room. And then this guy comes on and everybody is totally transfixed by it.” I wanted to know more about why that was. At the end of the gig, Dudu was at the bar. I went up to the piano and started playing one of his pieces from In the Townships. I went on and played the whole album. Eventually, Dudu’s wife said “This kid is playing your music—look.” So, Dudu came up and sat down next to me. Suddenly, we’re playing together through the pieces from the album. It was total heaven for me.

A few weeks later, I got a call saying “Do you want to do a tour with Dudu?” And off I went to Europe. I was playing that music with his band and Harry Beckett. I learned about the European jazz scene and saw how it worked. After every gig, we’d get in the van and Dudu would play a recording of the gig. We’d all have to listen to the whole gig really loud so we could determine what needed to be developed, figure out another way to play around a sequence, where we should play a groove, and find new ways to harmonize things. That process was also a great influence on me. We made an album called Life in Bracknell & Willisau in 1983, which was my first recording.

You’re a Professor of Jazz at Bern University of the Arts. Describe how the role emerged and why you chose to relocate to Switzerland.

Becoming an educator happened accidentally for me. I didn’t receive any formal education in jazz and improvised music. I was slowing down records and transcribing things when I was a kid. I had one small conversation about interpreting chord symbols with Kenny Wheeler while attending a jazz course at the age of eleven. There were little bits of this and that. When I was ready to go to college in 1979, there were no jazz courses. Now, there are so many, you fall over them. [laughs]

My first experience teaching happened with Loose Tubes. Someone told us “You can have this gig, but you need to do some educational stuff in the afternoon, otherwise we can’t justify it. It’s part of the way we work.” We said “Okay, we’ll do it.” We’d go there and it was all very intuitive. We’d play with young musicians and see what they can come up with. But if someone was struggling, none of us had a strategy for that, initially. The more I did it, the more I realized I liked talking about music. It made me think about what I do in a different way.

In 2005, I went to Copenhagen to become the Professor of Rhythmic Music in Denmark, at the RMC in Copenhagen. I did that for six years. During the last year, I was asked to become more of an administrator than a musician. At that point, I knew I had to escape. I visited Bern as an artist-in-residency to run a big band playing my music. I got to know the lady who ran the jazz department at the Bern University of the Arts and said “If there’s ever a job available, please let me know. I’m looking to escape.” She said “I don’t believe that.” I replied “Yes, seriously. I need to get out of where I am.” So, she pretty much created a role for me and I got the gig.

I found a place to live in Old Town in Bern and once I was settled, I thought “Wow, I’m sitting in this room and it feels like the first time I’ve been on my own for 12 years.” The silence descended and it was incredible. I felt I could build on that feeling and make some big changes to what had been quite a fragmented, disrupted life for several years. I met a lady who was very different to any of the other people I had spent time with. She was a single mother with a young boy. We got together very quickly and I wondered “This is happening so fast. I already have grown-up children in England. Is this a good idea?” Then I thought “Well, that’s just the way it is. Grab it! Make it real.” [laughs]

I felt teaching was related to the jazz club I told you about where I first played with Dudu Pukwana. During the day, I would do things like washing dishes in a restaurant to pay for buying van I could use to take the electric keyboard to gigs. I loved that life. It made me think about the Bird Lives! book. I thought “I’m living that life and it’s exactly what I want to do.” It seemed like washing dishes was gradually replaced by teaching.

I was once in a car in Bern and got stuck behind a garbage truck. The men were jumping off and on, picking up rubbish bags and throwing them into the back of the truck. I genuinely felt “I could do that. Nobody’s going to judge me if I did. It’s so straightforward. You know what to do. That goes in there.” There would be a feeling of satisfaction as the rubbish got chewed up by the machine. I’d exercise my body and be outside. I felt perhaps I could do that for a year and have a counterbalance to music.

The point here is I always felt I would always pursue my own music utterly on my own terms. To make that possible, I would have to do something else as well. Composing is all done on my own. I don’t play live that often. I don’t get that many opportunities to do so and that’s because I’ve turned a lot of opportunities down. We talked about how in the early days I used to say yes to everything. I’d play with singers who had no charts in pubs, that really weren’t singers. I’d play disco all night. I’d play in all sorts of jazz groups in which I didn’t know anybody. After years of that, I thought “I’m done with that now. I need to stop.” But the phone kept ringing. My number was in all these books these function gig bookers used. I remember when they’d call after the decision, I’d say “Thanks very much, but I’ve decided to just play jazz.” I didn’t realize that to those people it was like words from a Martian. Typical musicians never said that. Everyone always wanted to play music all the time, but here’s this weird kid saying he’s only going to play one kind of music. I had to say it many times before it was understood.

I try to be realistic now, as well. Nobody wants to record an album and just do two gigs. Once they’ve made an album, they want the project to continue and for it to have a life. I can only manage to do that with two bands and they might as well be my own bands. The exception is Anouar’s group. It’s good to have an exception that proves the rule. [laughs] So, that’s my overall view of what I’m doing. I’m lucky teaching feeds into my other work.

What broad philosophies do you impart on your students?

The most important thing I do is help people find their own voice. That might sound like too much of a cliché, but I actually think people who choose to study in the field of improvisation are uncertain about that. Perhaps they’re uncertain about whether or not they’re allowed to do what they want to do. They might wonder if there’s a career at the end of that approach. For me, that isn’t to be considered at all. I don't believe anybody knows what will happen in terms of their career. If you’ve found your voice, you’ve got your voice. It doesn’t matter if you’ve got a career in music. Music might be the thing you do because you love doing it, not the thing that allows you to go to the food shops. I don’t think there’s any point in pursuing music unless you’re finding and using your voice. That’s it. You could be playing other people’s music or writing for others and still be using your own voice with both.

Your Stormchaser group from the mid-2000s was drawn from your post-graduate students from the Rhythmic Music Conservatory. Tell me how that ensemble came together.

Every Friday, a group of really dedicated students would meet up with me. I later discovered they weren’t getting any points towards their studies from doing this. They’d all be out all Thursday night partying and turn up feeling pretty bad Friday morning. [laughs] For no study reward, they’d challenge themselves by performing various experiments of mine for three hours. The group had Petter Eldh on bass, Anton Eger on drums and Marius Neset in the saxophone section. Anton would go on to work with Phronesis and have a serious career of his own and Marius is world-renowned now, playing his own music with ensembles like the London Sinfonietta.

I found I could write anything for the saxophones and they’d never complain. They could always look down the line and see Marius playing everything, so they went with it. [laughs] They were very supportive. It was great to see what was possible. It was a bit like I imagine Charles Mingus worked with his Jazz Workshop group, which went on to record Mingus Ah Um. It was a good example of teaching feeding back into my music.

What’s your take on the economic difficulties musicians face in the current business and consumer environment in which recorded music has negligible monetary value?

This is going to be a slightly lame answer, but I really don’t know. I don’t want to give you the answer that says we’re all doomed, but I'm not going to tell you everything is great and that I have a solution. I’m just like a lot of other people, just trying to work it all out and see if there is an alternative way forward that no-one has thought of. That’s the best way I can put it. It’s just in my nature to bring out recordings. It’s a document of where I am and it would be really tragic if people stop doing that. When you make an album and put it out there, even if nobody pays for it, it’s your permission to move on to the next thing.

There’s a lot of public and private funding for recorded music in Switzerland. Have you considered exploring those avenues?

Previously, when I made albums, I tended not to make a new one until the previous one had recouped. Now, it’s a different environment. But I have an aversion to filling in those forms. I like the idea of the thing paying for itself. I realize even in England, there’s a system in which people can apply for funding for artistic things. But you’ll find that the things that do get funding quite often have many politics behind the decision. I quite like avoiding that and surviving outside of it. In general, I think there are quite a lot of constructs I like to survive outside of and sometimes that makes life quite hard. I’ve accepted that certain promoters won’t work with me because I’m unable to play the game of doing things exactly the way they want.

You have a deep interest in socio-political issues. What role do you feel musicians should play in addressing them?

I think awareness is always good for everybody. How people deal with the issues they become aware of is a personal choice. I can write a piece of music that has no specific subject matter or arrange a Charlie Parker piece in a very personal way. I can also decide it would be nice to play an arrangement of “The Times They Are-a-Changin’” in the middle of a set, done in a very beautiful and reflective way. I can make small gestures like removing the plastic bottle of water that’s always next to the piano on stage at gigs. I'm so sick of plastic everywhere. So, that’s another tiny thing. There’s also the possibility of trying to build music around an attempt to change the world. I’m not sure that’s possible. I think it’s about finding a balance that works for the musician and is honest.

When Brexit began, I found some quite amusing ways of talking about it from stage. I thought what I said was amusing and honest. I also wanted to apologize to people as well. When we would play in Germany, I wanted people to know my position on it. I wanted them to know what I thought. I made it clear I wasn’t responsible in any way. [laughs] But after a while, I thought “Fuck Brexit! I don’t want Brexit at my gig anymore. I think it’s time to not discuss this from the stage.” I might bring it back. I go with the flow.

As for the music itself, I believe it can communicate real honesty and expression, and can show people pursuing a dream. I hope that communication can be refreshing for the audience. It really does feel important right now. What I and my colleagues and friends do is quite child-like and we all believe it’s worth doing.

Your album covers and publicity photos are sometimes quite extravagant and intriguing. Tell me what you’re going for when you create those images.

The visual thing is great, because it’s separate from words and can’t be confused with the music. It’s just something to look at. It’s very simple, really. I’ve seen many thousands of photos of slightly shabbily dressed musicians up against a wall, all looking uncomfortable. [laughs] When you get to a festival and you want to look and see who’s playing, you think “My God, another one of these photos. This is ridiculous.” Very early on, I thought, we can take this and do something different with it. The wings photo I use has to do with Bird, as in Charlie Parker. The experience with that photo has been tremendous. It was taken at the time of the 2009 album Belovèd Bird. Festivals still use the photo and sometimes ask if they can use it as the festival poster or the cover of a program. It sometimes turns out it’s the most interesting photo they get. My most recent studio photo, at the top of this interview, explores the idea of my “40 years outside the box.” Hopefully that makes sense when you look at it.

You have a sardonic sense of humor. What role does humor play in your music and its presentation?

In Loose Tubes, everyone in that band could have done improvised stand-up comedy on any given subject. That’s the way it was. It would have been ridiculous to not have brought humor onto the stage with us in some way. We did that to different degrees. Then I saw a Jan Garbarek gig in which none of the musicians spoke to the audience at all for the whole show and I was really impressed. The audience loved it. He didn’t have to think of anything to say and the music was great. I thought “I’ll try that at the show tomorrow” but it didn’t work at all for me. But occasionally, I try to say less. With Anouar’s show, he only announced the band once during the concert and there’s nothing else that needs to be said. It’s all about the music.

Going back to Loose Tubes, the music was very dense and for some people, it seemed like our concerts were “intellectual events.” So, we’d also say “Don’t worry! We’re in this together. It’s just stuff we like doing. You can join us for the experience and we’ll have a chat later.” We were trying to thwart expectations and perhaps be clever by turning things upside down that way, hiding the the complexity of the music. Sometimes the music itself in that band made people laugh. These days, as I described earlier, I do put myself in the audience when I’m writing music. Unlike when I was in Loose Tubes, I don’t feel the need to do sudden cuts from one thing to another. I don’t really want to pull the rug out from under people’s feet anymore. I want to get from one place to another and have a development section that enables that to happen. Today, my goal is to be as closely connected to the audience as possible.