Donate to Innerviews

Since 1994, Innerviews has provided uncompromising, in-depth interviews with musicians across every genre imaginable. And it does that with no trackers, cookies, clickbait, or advertising.

Your donations are welcome to help continue its mission of highlighting incredible music and artists, without any commercial considerations.

Your contributions will be instantly transformed into stories and videos, and cover hosting and web management costs. Importantly, your dollars will help ensure Innerviews remains absolutely free to all visitors, independent of their ability to financially support it.

Please consider making a donation today by using the PayPal QR code below.

Kai Eckhardt

Unknown Zones

by Anil Prasad

Copyright © 2001 Anil Prasad.

It’s a blustery winter’s evening in Berkeley, California, home of bassist-composer Kai Eckhardt and Innerviews. They're taking refuge from the elements at Maharani, an Indian restaurant that’s a favorite hang-out for local musicians. Although the dinner is scheduled as a one-hour interview, a five-hour, largely free-form conversation ensues instead.

Over steaming plates of palak paneer and curry, the renowned performer begins the discussion by exploring the creation of his recently-released debut solo album Honour Simplicity, Respect the Flow. The title reflects the disc’s no-compromise, organic vibe. It’s a jazz canvas painted with world music and ambient brushstrokes, framed with Eckhardt’s remarkably fluid, often chordal basswork. With no edits, overdubs or concessions to "smooth jazz," the release stands in stark contrast to that proffered by today’s mainstream jazz industry. Eckhardt’s stance is unsurprising given his philosophical leanings. He believes honesty in art is directly related to the arenas of human rights, the environment and spirituality. Further, he postulates that corruption in one realm has significant ramifications for the others.

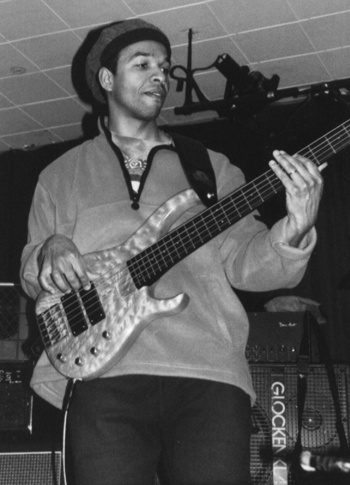

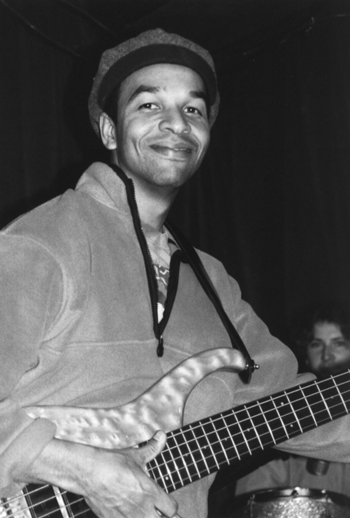

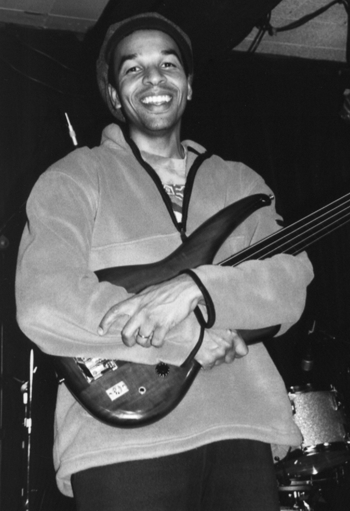

Eckhardt, a youthful-looking 40-year-old, is decked out seasonally in an orange polar fleece sweater, a gray beret and faded jeans. He's an animated speaker who delivers his passionate words across a continuum of emotion, inflected with a unique accent mirroring his Liberian and German roots. The restaurant's owner, a diminutive Indian gentleman, hovers around him throughout the interview, attempting to politely eavesdrop. Eventually, he works up the courage, walks up to Eckhardt and snaps his fingers at him a couple of times. "Hey, you’re that guy who plays with Zakir Hussain, right?" he exclaims. "Yeah, that’s me," responds Eckhardt, who proceeds to engage the owner in small talk about his "sideman to the stars" exploits.

The scenario is one Eckhardt is used to. Having performed and recorded with jazz legends including John McLaughlin, Gary Burton, Trilok Gurtu, Randy Brecker and Stanley Clarke—just to name a few—face recognition often comes before name. But the solo album and regular gigs with his new band Garaj Mahal are slowly but surely reversing that order.

Featuring guitarist Fareed Haque, drummer Alan Hertz and keyboardist Eric Levy, Garaj Mahal offers up a unique jazz, funk and world music hybrid that balances deep groove and improvisatory leanings. The virtuoso-laden group regularly performs in the Bay Area and across the Northwestern United States. It's also experiencing significant critical acclaim from both jazz and "jam band" circles since debuting last year. The group is currently putting the finishing touches on its debut album for release this fall.

Since joining Garaj Mahal, Eckhardt has made significant waves with words as well as music. In August 2000, the group performed for an unreceptive crowd at Broadway Studios, a nightclub in downtown San Francisco. It was a case of the audience drowning out the music with incessant, disrespectful chatter. And one that sparked Eckhardt to tell the crowd exactly what he thought of it. The event also motivated Eckhardt to write a charged treatise about the current state of artist-audience and artist-industry relationships. The controversial letter, reproduced in its entirety after the interview, has drawn praise from musicians and listeners across the globe. But there are dissenting voices too—one of many topics discussed in the wide-ranging exploration that follows.

Describe the genesis of your solo album.

I decided to do one a long time ago, but the circumstances were never right. The first time a record company wanted to back me up was back in Germany in 1982 with a really small budget. I wouldn't have been able to get the musicians I wanted to play with, so I passed on it. I ended up doing a lot of work as a sideman—which represents most of my career so far. But I was always writing on the side. I did a ton of that in my own time. But I was never very aggressive at pushing my own ideas. I always felt if the time was right there will be a moment. I didn't want to rush it. So, it took me eight years to lay the egg. [laughs]

I understand you've been seriously composing since 1990. You must have built up an enormous wealth of material.

Yeah, I had a lot of things stored up. Not everything is necessarily good. Some are ideas I scrapped and then went on to other things. What happened on my album is the result of what the musicians brought to the table. There's a few things I was a little concerned about. I didn't want the music compromised in any way. I've been observing how other people work on their records—a feature of being a bassist. You really get a lot of time to listen to other people doing their thing. As bassists, we are generally in a supporting role except for a few moments. One thing I didn't want to do is disrespect the spirit of the art or music. Of course, we have to make a living, so a lot of things I do and collaborate on right now are not necessarily what I'd do if I had freedom of choice. When it comes to true art, there has to be a vision that has been germinating for awhile. Second, the musicians that participate have to have freedom of expression. I cannot hire a great musician and tell them what to do. Third, the record cannot be done in a rush or under bad circumstances. In other words, not having enough sleep or showing up in the studio unprepared, not knowing what's happening. I took care of all that I could to deliver the project as something with high artistic quality.

The first thing I did was take the band including the piano player from Turkey—Aydin Esen, and the drummer Sean Rickman from Washington and flew them to Austria. I was giving a master class in November 1999, and I brought them into the class with me. They helped me teach the class. The subject was "The art of the trio." So, I rehearsed the tunes with the band in front of an audience. We involved the listeners in the process. Then we did two concerts in front of a live audience the next day. The day after that, we went into the studio. That's why I think the record is a success. I've listened to it many times and I know when I'm 90 years old I'll still enjoy listening to it. What other people think, I don't know. They might think the whole thing is a little crazy or inaccessible or whatever. But I know I can put this behind me and move onto the next thing.

Why might someone perceive it as inaccessible?

Because there are hardly any patterns on my record. Everybody knew what the music was. There was a sheet with melodies and chord changes. Some of the bass lines were written out ahead. But the improv is free-blowing. I chose Aydin and Sean because of their abilities to improvise. For instance, if you were to transcribe a drum track, you would end up with 30 pages because he's playing things differently each bar. It makes it so incredible to listen to because the time is so rounded and it grooves and swings the whole album through. It's the same way the piano player plays. He's someone who's very good in classical and jazz, so he has an almost 12-tone approach to harmony. So, there are these soundscapes that come at you that sound very unfamiliar—almost like molecular structures of the universe. I really like that right now because it means I can lose myself in the music. It's hard to describe. It's best to just listen and keep time while listening. The main thing though is please don't put my music on as background music, because it's not going to work. But if you focus on it—take some time to really listen—I think it really works.

You feel very strongly about the parallels between the loss of artistic integrity and loss of connection to the Earth. Elaborate on that idea.

I'm horrified at what's developed. I'm talking about mainstream commercial music. I'm not talking about artists that are always doing what they do to be sincere—to create beauty from art and express real emotion. I'm speaking of that which is claimed by the mass media as the most important thing everybody should listen to. I do see a connection between the decline of art in the Western world and the loss of connection to the planet—the cycles of nature, the beat of the planet and the rhythms inside the universe. If I sit down and take my bass out and play one note and keep that note consistent for half an hour, I'm already doing something right there. I'm doing a service to myself and the universe. I'm staying consistent. My mind is focused on something that's not going to hurt anybody. There's vitality to the beat. Everyone can sense it on the inside. My organs are vibrating. It's my desire to tap into that—the sound of my organs, my mind, what's on the other side of my body. I want to penetrate that with my music so I learn the rules of what is good art and what is not by trial and error. If I'm consistent, what happens if I'm inconsistent? In 20 years, I've learned that is diametrically opposed to the principles inherent in mainstream culture.

Can you describe those principles?

First of all, there's a fear of risk taking. Most artists I see on television rely on production. They are terrified. I know a few cases of very high profile artists who hire great musicians and then have them play along with pre-recorded tracks just because the main singer wants it exactly like on the record. You see that a lot—the precision, the fixation on technology and fashion. Fashion as the center of the universe is what holds it all together. Fashion is a commodity exploited by people who have little more than an economic interest. It's kind of a death trap because the marketplace has become so heavy and dense that it is pulling on everybody—even the most sincere artists who believe in sacred elements of music feel this pressure to bend down and serve the commercial God. If they don't, they get penalized and they will not make a living and cannot afford to have a family.

There are many ways you will be punished if you're not part of the mainstream system. It's an interesting phenomenon because I think it's directly connected to the fact that the Earth we live on is being exploited to such a large scale. The Earth is giving distress signals. But the outlook of the mainstream economy says "exploit more" and "more growth next year—generate more income for everybody." The Earth is saying "I already cannot keep up." So, this brings us to the subject of what is honest music? Which God do we serve? Can I worship on two altars at the same time—the altar of commerce and the altar of truth? I've had this question before me for a long time. I'm speaking to you at a point of major transition. I'm seeing a lot, but have not found my way. I have not made peace with what is going on.

Let's explore the meaning of honest art.

What is true art? What is the responsibility of the artist in the United States? We're in the first world. We're in a major urban center. We have access to news and music from around the globe. We have access to information through the Internet. We have more choices than we've ever had as people. The record stores are flooded with more than 30,000 new releases every year—that's the number I got from someone in the industry. Why even put out more music? What's the value of adding just another album? The answer is that art has to have some characteristics to be honest.

Art cannot afford to be self-conscious. The motivation is a key factor in determining if art is honest or not. It has to be something that comes from a personal experience that gets translated into music. If somebody says "I'm going to cater to this market," then it's not honest art. However, I'm not saying that type of music is not valid. I am someone who has two children. I can't afford to not making a living. So, I have to bow down to the rules of the market even if I don't like them. But I don't like the rules of the market. I think the market is at a point where it needs to undergo a transformation. And it has to come from the grassroots—the people who are honest artists. In other words, people who look at the environment and translate that experience into an artistic medium. Then they send that picture out there. True art is also related to people standing up for human rights. I think human rights are directly connected to music. To explain, let me backtrack and go into the process of creating my album.

I already mentioned that the musicians were treated well. They were also paid well. They had what they needed to be comfortable in the studio. There were not rushed. I made sure to tell them "I honor you for who you are. I thank you for coming to grace my album with the beauty of your spirit. This is the music I wrote, but do with it whatever you please. I will be happy if you are happy." What they gave was 150 percent of their spirit. It was a beautiful experience working with them. We had some very nice musical moments. To tie this back into human rights, I want to see a change happen in this world before I die. I hope it for my children and everyone else that people put the human being first, before the product. Nowadays, you're starting to see an image society is painting of itself. Every nation is struggling. Right here, right now in San Francisco too. What is going on here in the media is a mainstream consciousness reflecting a desperate need to self-perpetuate something that is intrinsically destructive. I would say it's blasphemous in relationship to that which creates life.

Specifically, what is blasphemous in the relationship you describe?

This is a heavy statement. I think what is blasphemous is that if you look at how commercial music is being produced, you see a reversal of the creative process. In any regular creative process, the human being has some kind of vision—some kind of impulse that is coming from within. It is something that is being brought forth. The impulse comes from a space deeper than the ego. As we all know, we are not just Kai or Anil. We are here and it is a miracle. I saw my two children being born. I had to bow down to this force and say "I do not know how you do what you do, but here they are. They look like me. They have this intelligence and spirit that is already there." You look into these baby eyes and you see a spirit that is cognitive. It just hasn't developed to communicate its vision or experience. But it's truly there.

So, back to square one. Art is only relevant to the human condition we experience. Otherwise, why would we bother spending all this time on something that is materially not tangible? Music evaporates once you do it. So, the reversal I mentioned earlier is that you take that which is below and you turn it on top. For instance, a young, bright spirit comes to this planet and has talent and a gift that other people recognize. So, that person becomes a musician and plays for an audience. Some people say "Oh, great! Record this performance." And they have technology advanced enough to capture the moment. So, they record it and make duplicates of this product and sell it so everybody can enjoy it. What happens then is once the creative event is stored on a medium, it is removed from the original process and can become a commodity. You can sell it, distribute it and soon other things are attached to that product that have nothing to do with the person who created it or their experience or what they wanted to do, good and bad. It can be great—an artist can make a lot of money selling records. But it can be bad, because you have a river that doesn't have enough power to get to the ocean. The water backs up and the toxins don't pass. Then you have people who get polluted because as the river backs up, epidemics begin. With the reversal, you have a gigantic industry used to large returns from the labor of artists. And now the industry wants to perpetuate those returns using artificial methods to create more and more. What I mean by artificial is everything from the counseling of the artist about what kind of image to develop or cater to, and the effort to predict the market—to say this is what people want to hear next, so "why don't you do this and that?"

The people in marketing departments used to say "Hey, look at this great artist. Buy this artist's work and support him." Now, they are in control and telling the artist what to do. This is what I mean about reversal. Now, if you are someone who is a creative genius and you were just getting started and nobody knows who you are, you will have a much harder time getting understood than even 10 years ago. That is something [John] McLaughlin told me. I believe him because you now have a generation of people who are not able to pay attention. Why do you have that? Because they are desensitized by television, video games, and aggressive advertising and marketing.

What do you make of the fact that marketing has become such a scientifically manipulative endeavor?

The energy the psychologists and analysts of the marketing industry put into making people buy products is just now yielding its bad fruit. They have trained a young generation of people to get hooked on things that are actually destructive to them. And these marketing people do not take responsibility for it either. Here I am as an artist. This is my view and I happen to live in a country in what I am speaking against happens to be very prominent. I have kids. I have to make a living through music. It's all I can do. So, as I said, I am facing a dilemma. Sometimes you see me playing on someone's record as a craftsman, delivering whatever they want me to do. Then I go home and work on my own original concepts. There is a big cliff between those two right now. There was a time when I thought I wanted to reconcile those two things. I wanted to something that sells and is commercially accessible, yet has enough artistic spirit in it. I now know that's not what I want to do. I cannot worship on two altars. The way I decided to do it is that when I am a craftsman, it's a clear-cut situation. I'm making the money, but treating people with respect and being true to my principles of being a humanist when I do it. When you hire and pay me to work on your record, even if the music is not what I believe in, I will put my opinion on the back seat and treat you with the utmost respect as a human being so you are happy at the end of the day. This is what I call being responsible. I think I've solved my problem internally by really keeping these things separate—craftsmanship and artistic creation. I am more interested in artistic creation. I have been coming up with some new ideas about how to create art that might relate to people who are desensitized or people who come up with high expectations of receiving a thrill to the senses—those who might not be interested in participating in the event.

Tell me about the new ideas and the path that led to them.

I hit a crisis point last year when I realized that I was on the road for six months out of the year with one child and a wife at home, and a second child coming. The marriage was difficult. Family life was difficult because I wasn't present in my children's lives. The road started to become a routine. So, I looked at both sides. The positive thing about touring is there's good money, a steady income and relatively high profile work. The negative was the family situation was deteriorating, so I decided I was going to make the move. I spoke to Trilok [Gurtu] and said "I cannot be full-time in the band anymore because of my commitment to home. I want to invest more in being a dad." He said "Okay, but I need to hire someone full-time and therefore I won't be able to take you on the road." So, I had to let that go altogether. I still did his last album. It was nice to reconnect with him on that level. But then I was faced with the dilemma of local work.

Being local, you soon run out of options. Local work pays really badly. You might be able to do it if you play every night, you're single and live in a studio by yourself. But you cannot put a child through school with it. So, I was figuring out how I can make some money, being what I am which is a highly-specialized artist who is now off the road. My main sources of income now are teaching, studio work, local gigs and smaller tours. And now, I have an album and that is starting to create my first little royalty checks. I'm in the struggle of building up a better infrastructure. I'm multitasking a lot. It's a diverse portfolio. I teach in my studio and rehearsal space in Oakland. I don't work at home. I don't have instruments there because the kids would trash them in a second. [laughs] I have students locally, as well as in Germany, Austria and Colorado. However, I also wanted to come up with some ideas and do something humanitarian.

Even before I was a musician, I was working with old people, the handicapped and thinking about world peace. I thought about what people have to be like if they are to solve the problems of malnutrition, overpopulation, the disparity of wealth, the problems with the climate—you name it, the whole nine yards. So, I looked at society and thought "Okay, Kai, why don't you try this? Come up with a show in which you take care of all of its different aspects." Then I looked at the history of my ancestors. I am from Liberia. I lived there as a kid. My dad is the son of a tribal chief. We are part of a tribe called the Kru. We have an aural tradition of passing the legacy of our people via the drums. The idea of ancestors speaking to us resonates with me at some level. So, I always mourn when I see a polluted river. It hits me at the core. I feel pain because I know my body is made of these elements. The water flows through my blood and the air goes through my lungs. I wanted to create an artistic forum to address the grief at what is happening and have a place where people can vent about the things they believe in. Problems can be dealt with in an artistic way by avoiding confrontation and bypassing political struggles about people fighting over petty little things.

I came up with the idea of writing a myth of modern society called "A modern fairytale." It starts in the spiritual world where a young being incarnates. There's a little dialogue of the spirit in its timeless form. The being becomes restless in the birth process. It doesn't want to be a witness to the universe, but rather a participant. It receives a body of flesh and bones and comes to the Earth. It's a musician and it cannot make a living and turns to the business world. It becomes a very successful businessperson and makes it all the way to the top of a corporate merger. Then, in its dreams, it meets the devil. The devil comes in the form of temptation, power and the fruits of the material world. "You can have it all if you join in," he's told.

It's a 20-page story. I wrote it and created seven compositions that have lyrics related to the subjects. I arranged it in my studio as a one-man show. I programmed samples, sound effects and a backing track with a drum machine. I also taught myself how to play bass and sing at the same time. Then I invited a select audience featuring people who excelled in a field other than my own. For instance, there was June Jordan, an African-American poet; two women that head up a non-profit organization protecting Native American rights in the Bay Area; and a friend of mine who is a venture capitalist that knows how the marketplace works. So, I performed for them and then involved them in a discussion. I did the show five times last year for 10 people in my studio. I also went to Austria and performed it in German.

I asked those in attendance what they thought of the idea of taking a group of artists and having them target a big problem in society like AIDS, pollution, the widening gap between rich and poor, the shaky economy, vanishing indigenous societies and the other things that scare the shit out of people when they take a closer look. A local topic could be the big problems with the water sheds in the Bay Area. There are too many people accessing fresh water and not enough clean water is available. So, you have the problems of MTBE leaking into the ground water. This is why we have a high cancer rate in the Bay Area. I highly recommend people don't drink tap water in the Bay Area. So, you have the oil companies involved, the company that purifies the water, and the people suffering from diseases related to the contaminated water. If you have someone with cancer who can trace it back to MTBE and they talk to the CEO of an oil corporation, they'll be really mad at each other. They are dealing with the same topic on opposite sides. It'd be explosive.

The idea is for the show to reflect issues from all sides back to the audience. During the show, you relinquish your ego. I come and offer myself as an artist to translate real life problems into visual and acoustic art. I talk to the person from the oil company, take the material and work with my team of artists to put together a multimedia piece that does nothing but reflects what that person says in a respectful way in a manner that taps into the subconscious and makes you think. We will not be there to create controversy, but to show that perspective in parallel with that of the person who is suffering from cancer. I think this is the future to me. Art is a perfect buffer zone where you can take controversial material and reflect it back like a big mirror. The original purpose of art is to digest things that are hard to digest. It motivates a loose, open discussion. It allows people to address the future, look at the past, come up with conclusions and come to closure on painful issues.

A connection has to be made. What is happening in this society is the result of a disease. That disease is greed. People who are infected are not able to quit because they are addicted. But we haven't reached a point where this is admitted in the first world. We are looking at a collective addict that is saying "I can quit smoking anytime I want. I don't have a problem." However, if you look at the practice, the problem is there. I believe the problems we are facing collectively will not be solved by human beings alone. We have to call on a greater power, otherwise we will not prevail. I do not believe we can. So, art and reality will be my final statement—a vehicle the subconscious forces can use to their own advantage. They can play on us, the people, and hopefully come in with a message we can retain and apply to our daily lives so we can deal with the problems.

In the Broadway Studios letter, you said music "is a prayer in the most basic sense of the word, offered to the collective." Expand on that for me.

The conventional idea of prayer says you gotta have a religion. And depending on your religion, you say certain words. When I think about the meaning of music, it always brings me back to square one in terms of why did I start playing? What was it? I remember that music is what saved my sanity when I grew up in Germany in the early '60s as the only black child in not only the school, but the whole town. It was a bizarre experience. The situation never felt racist but it created a different kind of schizophrenia. I was looked at differently. The situation didn't become apparent until much later. I had a lot of emotional agony relating to the situation I was in, but I didn't know why. This is when music came in and made a drastic difference.

When I discovered playing bass at age 15, I went to it with such a vigor. I was completely absorbed in the act of playing the instrument. I remember I had my first real spiritual high when I was alone in my room playing bass in the window. I hit the zone suddenly and thought "If this would stay forever, this would be heaven." I was playing, it was flowing and I was hearing the ideas. The groove was there and ever since then, music is my primary way of praying and also receiving an answer to my prayer instantly. To this day, if I really feel bad, I can go to my studio anytime and walk out two hours later having set myself straight. No-one has to be around. There's a root experience and everything else is a layer on top of that such as technique, style, the audience, how to play in this setting, and variations. So, I'm saying that prayer is the best that music has to offer. It's a healer. It's an instant connection to God—to the Goddess if you will. I use both genders because I'm a firm believer that you cannot talk about the masculine without mentioning the feminine. They are nothing without each other.

What spiritual perspectives do you embrace?

I'm a homegrown religious guy. I have been in the Catholic church and with the Buddhists chanting. For awhile, I read a lot about Zen, emptiness, mindfulness and Rumi poetry—it's all incredible. I'm like a wanderer that checks these out and whenever things get too specific, I withdraw. I was baptized Protestant and went to church with my Grandma. I don't have to use words such as Buddha, Christ or Mohammed. All of these are heavily-burdened and loaded images that I prefer to bypass. I prefer to understand the essence of Jesus and leave the name alone. It's the difference between sound being a commodity and being a spiritual experience. It's in the ear of the beholder. As artists, we have a mission to educate and purify ourselves and pass this on to the audiences. There are a lot of people out there who are really, really lost. They don't have access or an interest in speaking directly to the divine.

Nowadays, real spirituality is right here. [picks up glass] This glass I'm holding is spiritual. What's important is that we know the meaning of the word "sacred." There are some things that are really sacred like human rights. We have to make the connection between human rights and the dignity of the human spirit. As we speak, the real problem out there is conflicting voices and motivations that are crossing. These need to be weeded out. We must understand the hierarchy of the alignment we all have with our inner energy forces. For instance, in order for me to stand up, my spine's gotta be straight, the feet are below and my head is on top. I don't get up with my head first and bounce around on it. [laughs] It's simple things like that. Wisdom and common sense need to be the masters. They must temper emotions, urges and the different voices in the psyche.

If we get tangled up in the marketplace and everyone is hustling to make a buck, trust is broken. The moment I no longer trust is the moment I'm taking wisdom and putting it out of the driver's seat. I'm letting desperation take over instead. Desperation is never a good advisor. It can succeed, but in a brutal way. So, if I put my record out, hustle and say "Everybody's gotta buy my record," it puts an energy out there which makes everybody uneasy—this frenzy of attention you seek. My prayer is to enable everybody to have easy access to art. If I was the master of the universe, I'd wave a magic wand and say "Let everyone have a sacred art form they can pursue that will untangle their inner conflict and put common sense in the driver's seat." With common sense, balance is restored. It's amazing, you have millions of people at conferences talking, debating and giving proposals that mean nothing because they haven't taken the time to see what's right. So, let's get them together at a concert, let us pray for them, let them join in with the players and just provide attention to the situation. If we do it well, they'll walk out feeling refreshed.

Let's address another quote from your letter that read "What happened at Broadway studios was more than I could tolerate. So, I asked for your cooperation politely and got absolutely no response. When I told you to fuck off, you finally gave me some attention. Sign of the times." How would you define these times?

Let's look at Marilyn Manson. Here's an artist who used shock value to get his message across to society. There's a danger to that. When everything is labeled entertainment, it doesn't have to be taken seriously. Everything can be seen as MTV's Celebrity Deathmatch. People are out there tearing each other up onstage and enjoying it like gladiators in ancient Rome. There's a danger of the grotesque in the situation. Now, audiences are ready to respond as soon as something gets ugly. It's only then they get the message and take something seriously. But anything subtle, they don't get. It sounds kind of judgmental, but it was an angry moment where things were black and white—shit was fucked up, you know?

Rhythm and sound function as a ladder to the universe on which the audience can climb on and go to really amazing spaces. They have to trust the musicians in order for it to work. If they don't trust, it sabotages the whole thing. We can still play the gig, but it comes short of being a prayer. Here's an example of someone. During the show, they'll say "Ah! Let's see what Kai is playing tonight. Oh, last time he played a different kind of solo. I liked his old tone better. Hey! Look at what Fareed's up to. Oh, he has funny pants on. Ooh, let me eat something here. Wow, there's some sushi. Hey man, do you think the band's cool? We're having a good time, yeah?" This is a profile of a kind of audience member—someone cluttered, who is analyzing out loud and is tuning in and tuning out. In an ideal scenario, everyone is there the same way they are in church. They are here for some relief. They check in and the music explodes—it goes through the roof. My ideas flow and that's when the metaphysical thing happens. But I can't influence this directly. I cannot force people, nor do I want to. I just go to my gig and think after "That was a good gig tonight" or "That was hard work." I always make an effort. When musicians are playing, there's a certain mental mode ready to deliver to an audience of living, vibrating people who are directing attention to the stage. That attention is very important. What I bring to the table as a musician is related to the audience and their concentration. I have to choose what to do in my moment of choice with the audience. How do I respond to the moment?

You've seen hostile crowds before. What was it specifically about the Broadway Studios crowd that elicited such an elaborate response?

I had an incident like this in Chicago in 1995. I was playing with Billy Cobham. I wanted to play an intro to one of his ballads, but the crowd was talking so loud that the people's voices were louder than me. Some things only work soft. I made the mistake of saying "Sorry, but I would like to ask you to hold off on conversation until after we play this sensitive piece." The next day, Cobham tells me "Man, don't ever do that again on my gig. The owner came up to me and asked 'Who does this bass player think he is to tell my audience to shut-up?'" That experience struck me as a kind of milestone. I really understood the reality of the classic entertainer—someone who has the same status as a jukebox. He's only there to make the crowd feel good. He or she is actually on a lower level than the audience—that's what I understood.

I'm there creating for these people, but if someone throws a stone at me, I cannot create. People don't do that today thank God. In the old days, they really did throw stones and cabbage. But today, we work with sound. If people are aggressively tuning me out, there's only so much I can do. I've learned to ignore that and do my performance, get paid and go home. But every time I work like that and accept lowering the artistic standards to please the paying crowd, I internally violate my own principles. I have to somehow keep them alive. If I violate them too many times, those principles will be gone. Capturing the moment onstage is like a deer in the woods. When you're really quiet, the deer comes out and you get a real idea of what's around you. But the moment a noise is made, everything disappears. The moment where there is silence is vulnerable. It's like a plant that first bursts through the surface of the Earth. It's very tiny and vulnerable and if one person steps on it, the whole thing is gone. But it could have been a redwood tree if it was given a chance. It is the same way with good music. There are principles that should be at work. Life is a lot harder than it has to be. Some people are a lot more stupid than they have to be on a large scale. There's more to it than "I pay good money. I want to be entertained. Bam!"

Do you feel this is a particularly American mindset at work?

Yes, this only happens here in the United States. There's a connection between the underdog position of the jazz musician and the slavery days. We all know what Mingus wrote in his great book Beneath the Underdog. At Broadway Studios, I was a black jazz musician who was addressing a 99 percent caucasian audience, most of whom were extremely wealthy. I found out later that more than 50 people there were from Askjeeves.com. There you have the stereotype of the rich person who uses the world as a canvas for their illustrious ego. It drives me mad. I'm black by default. I'm even half-white, but who cares? The strong response is still "Stay in your place. You have no right to talk to us like that." It just taps into the whole history of the United States, how it was founded upon rich principles and baggage that is still not digested yet.

Tell me more about your view expressed in the letter that said "We’re part of a society that has begun to polarize to such an extreme that we now have a paradise and a ghetto superimposed onto itself."

Here's a great example. I live in North Berkeley [California] in a nice, clean neighborhood. Life seems to be paradise with people here in their little gardens and beautiful cars. But I go to work in my studio space in West Oakland [a few miles from North Berkeley] where there are hookers, people high on crack 24 hours a day and homicides. I come in touch with that. I see it happening. I talk to people in the neighborhood. I'm not afraid of the ghetto. I've lived in Africa. I've hung out with cats who have nothing. They always have interesting stories to tell. I'm not afraid of people period. There is an imaginary line down the middle that asks "Do you have money or credit, or don't you?" There's a system in place to keep things segregated and separate.

Something has crystallized and hardened. Life is unbearable for a lot people in the United States. People are tuning out politically. They're not interested in anything. And people are not able to take care of because they are so whacked mentally. Some people live like animals from day-to-day, from one fix to another. They're just like vegetables. Then you have people who weigh 350 pounds and drag that weight around all day long, then sit and eat Twinkies all night long in front of the tube. The perversion gets rubbed in by the mainstream media industry because they paint a picture on television promising a paradise for everyone. They give people candy to latch onto.

Now, let's look at poverty in Liberia as I knew it before there was a war. I knew it during the war too. It was different than poverty in the United States today. In Liberia, you have a community where everyone is materially poor. Kids don't wear shoes. You have high infant mortality. Life is rough. But there are more smiles and laughter. And the beggars come up to you and they are super-humble. In the United States, a beggar comes up to you and says "Hey man, spare some change." If you say "Sorry bro', I can't spare no change," he says "Motherfucker!" and goes on cursing at you. I believe the mainstream media has something to do with the difference.

The media takes a person like Michael Jordan, mass produces his image on billboards, television, videos and magazines, and tells the average kid in the ghetto that he can be like Jordan, Puff Daddy, Martin Payne or another star that is selected. So, the black kid in the ghetto thinks "Yeah, I'm gonna start playing basketball and rapping." And what happens? How many of these kids become Michael Jordan? How many people win the jackpot? That's the fallacy. The media is telling us the way to success in American society is the lottery, but they're not telling you what the odds are. And when people find out, they become angry and violence and crime is around the corner. It's a vicious cycle. Drugs make you feel better, then you can't cope. Then you can't deal with a job interview. You lose your chances. You're in jail, an alcoholic or dead. The system has no way to bring people back from the bottom. The system prefers to exterminate them to get rid of them. It's "Let's find a way to shove them aside or lock them away." That's the way this society has dealt with its problems all along. That's what I'm talking about as far as the ruling class. It doesn't know about history. But they smile and say "Let's make a brighter day tomorrow for us and our children" on television.

I'm like a commuter between the ghetto and the first world. That's why I came up with the idea of the ghetto superimposed on paradise. There is a lie in all of this that makes it work. I don't know what it will take for the majority to benefit from the power they have to unlock our true powers—our grace, the beauty inside of us. I'm in the middle of this struggle. I look at my kids and think "God, I could pray 24 hours a day. Let there be a better way than that we're heading towards."

You've taken a significant step for yourself by ensuring you don't lose your focus as a parent.

Yes and that shows the schizophrenia involved in being a star. I'm supposed to be a star. "Kai Eckhardt, the bass player, he's worked with…" You can write the names down on toilet paper. In the marketing sense, I need to capitalize on this. This is my background and here are my records. I'm also supposed to be on tour and be all places simultaneously to beef up a career. Who suffers? My four-year-old son, my one-year-old daughter and my wife. So, I have to strike a balance. My career is unfolding slowly. I have always been slower than others when it comes to big moves in life. But I've always succeeded in a good way. I have a nice family. I have a nice album that is honest, fresh and has a high level of musical integrity. We did not use ProTools on it. We did not fuck with this music. We let the spirit talk the way it wanted to talk. We got out of the way. Sometimes the spirit is angry or whimsical, but you gotta let it talk and go through its emotions. You have to let it shine, vent and blow out all the exhaust. In mainstream society, you can't do that. The spirit gets edited before it opens its mouth.

Fareed Haque said part of the motivation for creating Garaj Mahal was to connect with the Grateful Dead audience. What does the group find attractive about those listeners?

Well, I don't really know what Garaj Mahal is about. It still has to prove itself in the record that we're making, as well as how we sit down together as a team and use our different ideas. The first problem is that we don't have a bandleader. But that can be a good opportunity to be truly democratic. It can also be a problem if everyone wants to backseat drive. Whether Garaj Mahal succeeds or not will depend on how that works out. What I want Garaj Mahal to be is a band that succeeds in making people dance. On top of that, I'd like this dancing entity to explore some territories that aren't usually explored because this band features musicians with exceptional mastery of their instruments. We're not a 100 percent dance band like Kool and the Gang. We're in this unknown zone.

As for the Grateful Dead concept, the good thing about that group is they managed to bypass commercialism by building their own audience base. They respected their audience more than other bands, allowed them to tape concerts, let them do psychedelics and be free. It was a very forgiving energy. It was a collective vibe that said "Let's all be a large group and rock on that big wave." Garaj Mahal also has some refined energies—the things Coltrane and Zakir Hussain stand for when they are tuned into mastery. It's a vulnerable space that needs to be set-up in order to come out. How do we combine the two? That is the question Garaj Mahal wants to answer.

Describe the origins of the group.

I first met Fareed when I was playing in Chicago with Ty Burhoe and Howard Levy. It was Fareed's home town, so he showed up, said hello and the next time I saw him was onstage with Garaj Mahal. Alan Hertz brought us together. He somehow got hold of Fareed. Fareed's an interesting character. He's half-Chilean and half-Pakistani. Like me, he's swimming between two worlds. I also relate to him in that he has multiple musical personalities. He has a classical side and a grounded, funky hardcore edge too. They're both in the same guy.

The band released a low-key, limited edition CD last year titled Gasoline Angel. What can you tell me about it?

That was our own bootleg. It was produced in a split second. Suddenly there was this CD. Someone backed it financially, and we quickly went into the studio for one day—a very spontaneous decision. You're not going to see many of those. It's a collector's item. It's got a great sleeve—all of these people in the back of a truck.

You're singing, rapping and performing spoken word material with Garaj Mahal—a side of you that's new to most.

Because of the music I wrote for "A Modern Fairytale," I started to sing. I meticulously worked it out because I could not sing before. I'm an amateur kind of singer. I only started two years ago. I literally sat down and went over the same thing over and over again. Initially, my voice would fall apart when I'd play bass. And then when I'd sing, the bass would fall apart. It was an ordeal. But now I'm at the level where I can comfortably pull off my songs. My voice sill needs a lot of work. I now feel I'd like to be recognized as a singer, if I can get there. I will definitely work on it. I have to acknowledge that I've been a bass player for 20 years and a singer for two. I consider myself a bass player who sings.

You're probably best known for your role in the John McLaughlin Trio and its Live at the Royal Festival Hall release. What made that record a modern touchstone for the jazz world?

It was McLaughlin's vision that made it all happen. He was the guardian. He ensured the artistic integrity was untouched and held up very high standards. McLaughlin made us work extremely hard. I had to outgrow my limitations. I had to practice with a bucket of cold water because my hands were so sore and I wanted that gig so bad. I felt limited because I only had been playing straight-ahead jazz and funk. Then there was Trilok's mastery. So we have Trilok, a renegade Indian with his own style and intensity, and McLaughlin who had experience with Shakti and knew enough about Indian music to match up. Then there was me. It's hard to say what I brought to the ball game that made it happen. I think it was my openness. I learned very fast. I had no reservations against what was going on. In my own way, I developed off the beaten path. That's what McLaughlin liked about me. I had to play for him solo to get to the gig. He found me through Gary Burton. McLaughlin likes to do detective work. He calls people up to find out what's going on. He shows up at people's gigs and sits in the audience undercover. He came to my apartment in Boston to audition me—he didn't even bring his guitar. So, one could look at the three of us and our backgrounds and how it all came together. There was a moment when three people intersected and we really all played for our lives. It takes more than the band—there's the audience, the Festival Hall, and the people who believed in and released the project.

What's a key memory of that tour for you?

In the dressing room of the Montreal Jazz Festival, we were about to go on. There was a little window and John is leaning out of it to catch some fresh air. The window comes down on his finger—it's one of those old Victorian ones that comes down like a guillotine. He yells in agony and somebody comes rushing in with a bucket of cold water. Within seconds, his fingernails are turning black. He's in terrible pain and we're thinking "Oh God, the gig's screwed." Then they announce the start of the show and he goes onstage and plays and sounds killer the whole night. The crowd is ecstatic and it was a great show. And he's hurting so bad after the gig. He did not have a good time. But he gave everybody else a good time. That was something I learned from him. You have performance standards. He would never go onstage stoned or drunk—never. In two years that we were on the road, not once did I see him wasted. The stage was his sacred space.

You've worked extensively with both Zakir Hussain and Trilok Gurtu. Describe the challenge of meshing with Indian percussionists of their caliber.

A challenge comes from the traditional approach to tabla as a tuned instrument. Zakir is very, very aware of the pitch of his tablas. He takes great care tuning it and always wants to know what key the song is in. Trilok has an array of tablas, so no matter what you come up with, he'll have a tabla ready and tuned in C Sharp, D or E Flat—those are the main keys of Indian music because of the sitar. If you're in any of those keys, you'll have no problem. Trilok and Zakir are both highly-developed and very different individuals in personality and approach to the instrument. Trilok's history is a lot more winding than Zakir's. Zakir I see through his direct connection to the lineage of Alla Rakha. There is an unbroken classical integrity. Then, when he came to this country, he started to branch out and meet other people. He also succeeded in becoming a great jazz musician.

Trilok left India and broke with tradition superficially. He left everything behind because he was seen as a hippie troublemaker in that some people believed he didn't respect the tradition because he wanted to do his own thing. He was seen as an outsider to society. So, he left India and ended up in Frankfurt, playing in the subway. He went through a whole street period and then developed his own style on his instrument by mixing parts of Western drums with a homemade set-up. So, he doesn't have any issues with tuning. He's more of a Western drummer than Zakir is. Trilok's come full-circle because he's being re-imported into India as a star. The Indians now think "Oh, Trilok, yeah!" But there was a time when it was "No, Trilok, no." Both Zakir and Trilok are spirits with individual voices you will never be able to copy. They will always be unique. That's the mark of a great soul.

Another artist of note you've worked with in recent years is Aziza Mustafa Zadeh. What do you recall about that experience?

Aziza is a nice addition to the variety that is in jazz. She is a monster. I did the album [1995’s Dance of Fire] and a tour. The tour featured Omar Hakim, Bill Evans, myself and Aziza. The session had the same guys with Stanley Clarke and Al Di Meola. Aziza is a child prodigy from Azerbaijan, the old Russian republic that is in a constant struggle with Armenia. There have been lots of political problems and life got really hard. Her dad was the famous, legendary jazz musician Vagif Mustafa Zadeh. He passed away onstage when Aziza was six years old. Her mother says he was heartbroken because he was never allowed to leave the country to meet his American jazz idols like McCoy Tyner. That's despite the fact that the President of the country had dinner at their house—they held that level of respect. Still, they couldn't jump over the iron curtain. The government wouldn't give that man a visa to come to the United States. Her mom thinks he died of a broken heart. I think for about a year-and-a-half after, Aziza and her mom didn't leave the house. But Aziza is amazing. She's a maniac who writes music on everything including toilet paper. She writes charts out that are seven or eight pages long with hundreds of notes. It's like a black sheet. Then you look at the notes and they're in girly handwriting with big circles. She came to the session on fire. She was coached by her mother. Her mother was always standing there behind the piano.

After the session, we went on tour to promote the record. It turned out to be difficult. There was a dichotomy between the jazz musicians with the American backgrounds and Aziza. She would play purely from her consciousness, but did not interact. In other words, information would go out one way and not the other. So, we ended up having to play with her. She would not play with us. I would say the tour was a partial success. I still think it was very interesting because the music was so deep. The harmonies and the Mugham style—the traditional music of Azerbaijan—had her really reaching out and improvising. She's a very sincere musician and doing well. But she's playing as a solo artist more or less these days. She's a woman who carries a lot of weight. She's a very Picasso kind of character. She's heavy into the art. She has massive character. She's a skinny little woman, but heavy. I've met some very interesting people—especially bandleaders whose personalities are not easy. They haven't had easy lives. They've gone through a lot of trials but have turned out in a beautiful way because they've addressed the challenges of their lives and didn't bow down to them. That's what makes them successful.

In addition to playing with Stanley Clarke during the Zadeh sessions, you also subbed in his band in 1986. Tell me about that experience.

We played at the McCormick center in Chicago. At that time, Stanley had a steady gigging band with a backup bass player named Jimmy Earl that played bass lines so he could solo more. Steve Hunt, the keyboard player, lives in Boston. We used to play together in Tiger Okoshi's band called Tiger's Baku. One day, Jimmy got sick. So, I was the next guy in line and I said "Yeaaaah!" [laughs] I had to learn "School days" and show up. There was no rehearsal with Stanley.

I was straight from Germany. I didn't know Afro-American language. I remember getting on an elevator with my bass and there was an Afro-American couple there dressed to the T. The guy looks at me with my gig bag and says "Like, so you're ready to throw down tonight?" I listened to that and said "Throw down? Throw down what? What am I throwing down?" They looked at me like "What planet is this brother from who just stepped on the elevator?" [laughs]

So, then I arrive at the gig and Stanley shows up with dark glasses. I'm introduced to him and shake his hand. I notice immediately that my hand completely disappeared in his hand. I remember when his fingers were hanging relaxed over the bass, it was like two Frankfurt sausages. I thought "There's no way I can compete with a cat like this." [laughs] I had this dinky little amp onstage. It was a Roland jazz chorus or something. Stanley had his big-ass rig onstage. When it came time to trade and jam, Stanley's like "Come on Kai! Come on Kai!" And I'm standing next to Stanley shitting my pants. He does his thing and he completely plastered me against the wall with his playing. But I was so happy to play with Stanley Clarke that I just didn't care man. Sometimes things happen in your life and you think "This cannot possibly be true." So, it was a great boost. Ever since, I've had a good relationship with Stanley. I saw him recently and he said "Kai, how ya doin'?" I say "I'm doing good Stanley, I've got two kids now." And he goes "You got two kids? Now you're really playing bass, aren't you?" [laughs]

You recently made a record with Count’s Jam Band featuring Larry Coryell and Steve Marcus. What was it like to work with the forefathers of fusion?

It was very interesting to work with Larry, Steve Marcus and Steve Smith. Steve Marcus used to be called "The Count" back in the '70s. He and Larry had a band called Count's Rock Band with Bob Moses on drums and Chris Hills on saxes. Moses and Hills came out of the Free Spirits, which is looked at as the first jazz-rock band pre-Chick Corea and Mahavishnu. They were based out of Portland, Oregon and were experimenting with jazz improvisation over rock riffs. The new album started when Larry Coryell and Steve Marcus decided to have a reunion. Steve Smith was the producer. Steve Smith and I have a long relationship through my work with Vital Information. I'm on Fiafiaga, the album with Tom Coster and Frank Gambale. I did multiple tours with Vital, so we're good buddies. Steve called me and said "You know, they're going to call this new band Count's Jam Band as opposed to Count's Rock Band." So, these masters of the first hour of fusion came together. Coryell came in with compositions in 17 odd meters, difficult changes, written-out melodies and difficult charts. Steve Marcus came in with the spirit of "Let's jam!" Steve Smith had to balance those two elements to make it happen. We had to loosen up on some things and let them flow. But we also had to pay some real close attention to the arrangements. We ended up with a very interesting album that's very raw and sounds close to real, energized jazz-rock of the first days. The first track has a real Mahavishnu feel to it.

We spent five days in the studio in Prairie Sound and really got to know each other. Larry did a little bit of chanting to get himself situated because he's a devout Buddhist. Steve Smith blew me away on the session because he absorbed the music quickly, produced it and also played some very difficult stuff. He also coached everyone through it. There was a lot of effort put in and some beautiful pieces came out of it. There are some real gemstone jams on it. I was also invited to bring in a tune. I managed to write one in the car on the way to the session. [laughs] I had been working with Indian rhythms and applying them to electric bass. I was coming up with patterns that work in 4/4 and I've also been working with parallel harmonies like taking one chord quality and moving it in fixed intervals. I like to move minor triads in minor thirds or major seven triads in major thirds. I always try to set up little symmetrical patterns and see what kind of melodies can fit over them. Then I build in my little home-made bass technique. So, I managed to write out a song like that and it was extremely hard for drums, but Steve pulled it off. It's the second song on the record. The bass and drums play continuous notes. We plaster everything with 16th notes, but everything is arranged with harmony and it never sounds busy. The melody is completely simple on top. Larry played it beautifully. Everybody was happy with the session. I highly recommend the album.

We've covered an enormous amount of territory here. Is there anything else you'd like to say to Innerviews readers?

There is an opportunity for growth. There's something in the bushes, but it is not going to come from industry. It's going to come from people like you and me that are taking charge and saying "I'm responsible for how events are unfolding and I'm going to create structures that reflect my beliefs and values."

I know a lot of artists read Innerviews. I want to call them to action and ask them to take their artistic integrity, knowledge and beautiful spirit and do something that will enrich the human spirit. Don't do it for the ego, because the ego will be taken care of. They should create art about what they are really concerned about as opposed to creating art to satisfy fashion and make money. If they are forced to do that and bow down to corporate culture, then at least do something on the side. Please get on with it now, because the time is getting late. It is a time of urgency.

Kai Eckhardt's Broadway Studios letter:

The incident:

On August 11, 2000, the band Garaj Mahal — Kai Eckhardt, Alan Hertz, Kit Walker and Fareed Haque — played a show at Broadway Studios in San Francisco. After an energetic set, the band decides to play quiet. However, the audience is so noisy having conversations with themselves, that the musicians onstage cannot hear their own music.

Kai Eckhardt the bassist addresses the audience in a cordial way and asks them to quiet down to no effect. After the piece ends, Kai gets mad and tells the chattering crowd how ignorant they are, and that they should get the hell out and get their money back.

What the band did not realize is that about 50 people from a popular Internet company had entered the room thinking that it was a corporate socializing party. Nobody knows who stood behind this misunderstanding.

Weeks later, Kai receives an angry letter from one of the offended audience members, saying that Kai had made an ass out of himself. To this letter Kai responds with a charged letter underlining the motive behind this response. He also addresses a bigger picture, exposing dysfunctional elements in modern society.

This letter sparks a line of controversy on the Internet. The letter also travels to the desks of Steve Smith, John McLaughlin, Jeff Berlin and Dennis Chambers, amongst many others.

The response:

To those that took offense at my comments during the Garaj Mahal gig at Broadway studios:

First of all, allow me to express my sincere apologies for what came across to you as a personal offense. Hurting your feelings or messing up your flow was not my intention. However, the incident did have this side effect and I clearly understand your being upset. I was angry and hurt. The choice was between letting off steam or going home with an ulcer.

I will not waste your time with half-assed comments about dot-commers or the corporate world. Instead, I will paint a coherent picture, one that will hopefully resonate with you. Many years ago, I became the apprentice of the great guitarist John McLaughlin. He in turn was the apprentice of the late Miles Davis, as well as a sincere student of Indian classical music. I consider myself part of a tradition and take a certain amount of pride in that. In the world of jazz, we look back on a tradition that is as much defined by its ingenuity as it has been shaped by trial and error.

The beautiful thing about this artistic tradition though is the love, devotion and vitality it yields to its adepts, as well as the genuine energy it is able to transmit to the serious listener. Tradition in that sense also means: A situation not only revolving around the here and now, but also encompassing all those that have passed before us and those who are yet to come. It is a prayer in the most basic sense of the word offered to the collective.

We, Garaj Mahal, are not elitists. We are serious musicians who believe in a sacred element within music and nature. We happen to be very good at what we do, and we can back it up all the way. We are humble and respectful toward you, the audience. But we also demand of you one thing: Involvement. Sing with us, listen, dance, trip, record, meditate, do whatever, but… do not ignore or disrupt. In that case, the music is damned to be superficial and we don't have time for that. In fact, it is easier to play for an empty hall, than it is for a chatter crowd. Sure, the whole thing was a misunderstanding to begin with, but it did bring up some issues that are worthy of being discussed.

You might think to yourself: Can't we musicians get in line with all the other dinner jazz players that are happy to have a gig for 50 bucks a night? No, absolutely not. Like a co-dependent who finally breaks out of an abusive relationship, we too have evolved. All of us have done "casuals" countless times anyway to pay the bills, and we can't wait to get out as soon as we get a chance. We do not care to play into an oppressive system that has humiliated and disrespected the greatest amongst us. For every jazz musician hailed by the critics, there are a hundred others who end up forgotten, with a broken spirit. The recent artist eviction in San Francisco is but one example of a bigger picture which is indeed disturbing, if not horrific. Am I holding you, the "dot-commers" responsible for a musician's hard life in a self-complacent society? No, but you contribute to the problem along with landlords, trendsetters and various other groups including us musicians who put up with all that shit. Problems in society are never that simple. Only you know who you are and to what degree you are contributing to the deterioration of inter-human relations. You are first and foremost human beings. So rather than getting defensive and framing me or my band as a bunch of sore losers, I invite you to look at our collective attitudes. I am holding you responsible for all this negativity to the degree that you do not care about what's going on around you these days. At least it seems that way. All I'm saying is this: Understand the connection between the soaring new economy and the soaring decay of natural ecosystems. Then choose your role consciously. That's all.

We, Garaj Mahal, are exploring what we believe to be the next level. Ready or not. We are not retro-oriented, but we do understand the past and take it seriously. We have a small circle of fans that understands what we do. They are loyal and they show up to almost every gig. We love them and respect them. They gave us our name. I will consistently see to it that their time is not being diminished by people who are out of sync.

What happened at Broadway Studios was more than I could tolerate. So I asked for your cooperation politely and got absolutely no response. When I told you to fuck off, you finally gave me some attention. Sign of the times. What will it take for people to finally wake up? If your response to my comment is the indicator, then brace yourself. If life outside the sphere of your persona only receives attention when busting out in violent anger or any other extreme, then that's exactly what will happen. There is no choice left then. (Oh yeah, it can also make you sick...) If you don't feel the distress of those whose groove you disrupt, it doesn't mean that distress is not there. It is there—part of the general ambiance. Modern physics knows of the connection between all things. We as a society have fallen behind. The machine is ahead of us.

Quantum physics knows that a particle on the subatomic level cannot be observed without reacting to its observer. So next time you pop a Tylenol, ask yourself if there might be a connection between your headache and the agonizing reality of that homeless person on the sidewalk next to the limousine, and the strip joint right outside the nice venue, where a rude bass player told you to fuck off.

What's this got to do with Garaj Mahal, my comment and the gig? A lot. We play from the space of unity. At least we aspire to reaching that space. Even if it means owning up to our collective shadow and even if it means enduring the backlashing wave of denial. We believe in looking out for each other and cleaning up our shit if we are responsible for it. We don't believe in the current commercial hype. That's what some of our tunes are about. But we're not just punks without an alternative vision. We do have one. We believe in art for social change. And we have some things up our sleeves that are yet to come.

We are part of a society that has begun to polarize to such an extreme that you now have a paradise and a ghetto superimposed onto itself. I cannot get used to it and believe neither should you. In fact, the reason that everything is being framed as entertainment has the purpose of converting everything and everyone into a commodity with a price tag on it—including pain and suffering. I cannot and should not have any respect for that. Meanwhile, there was a concert going on. A very special one. There was so much vital information there, it could have blown your mind had you only witnessed it to begin with. But what happens when a culture forgets how to tune in, because it has become used to being spoon-fed by the entertainment industry? What happens when a culture becomes self-centered and unwilling to recognize life outside the ego sphere? If that is the sad truth (and I sure hope we can improve on this...) then don't be surprised if your PC catches a virus with a funny name or if you find a brick on the seat of a brand new SUV parked in a poor neighborhood.

Don't be surprised when a few years down the line you grow old and weary of catering to a system that discards you as simply as it hails the new 'cat' that came to take your job. Anxiety, anxiety, anxiety. Stay busy, keep talking. The new economy is a machine. It feeds itself by virtue of ignoring the big picture. In fact, it has no eyes. I am not against you. In fact, I invite you "dot-commies" and other mainstreamers to begin working together with artists in a serious way. Admit there is a crisis. After all, we are one. We have ideas, that I believe have not been explored sufficiently.

I am human. I grew up as the only "black" person in my town during post-World War II Germany. Despite the inevitable racism, I became school speaker, and delivered the highest grades second to only one. I conscientiously objected the German army draft and cared for handicapped children over a period of two years. When my German foster father was dying of Parkinson's disease, I stopped going on the road to look after him, for another two years. I attended school in Liberia, West Africa, now war-torn. Many of my family members including my father became war casualties. I saw my two children being born at Alta Bates hospital in Berkeley. I care about them and they know who their father is, despite the fact that I am a full-time musician. What does it take for me as an artist in the Bay Area to keep my modest life standard and not head for the ghetto? Anything short of human sacrifice!

For you, the gig was just a party. For us, the band, it was an attempt at transcending time and space—a message in a bottle asking for nothing less than the secret of unity in peace and music. If you are young and successful and life is good to you, enjoy it fully. But please be aware that you walk on special ground—a ground on which many lived and died, many of whom experienced things you hopefully never will. But in honor of them who gave you life and your future children, please act in such a way as to put a smile on their forgotten faces. Whether the economy goes well or not will not matter so much. We will find our way to unity through the doorway of the human heart.

So come out again if you dare.

If you care about your community in unity.

This time not to schmooze, but to cruise.

For the beat turning your stress into heat.

Positive vibrations delivered across all nations.

Don't fake the funk.

Peace.

Kai Eckhardt