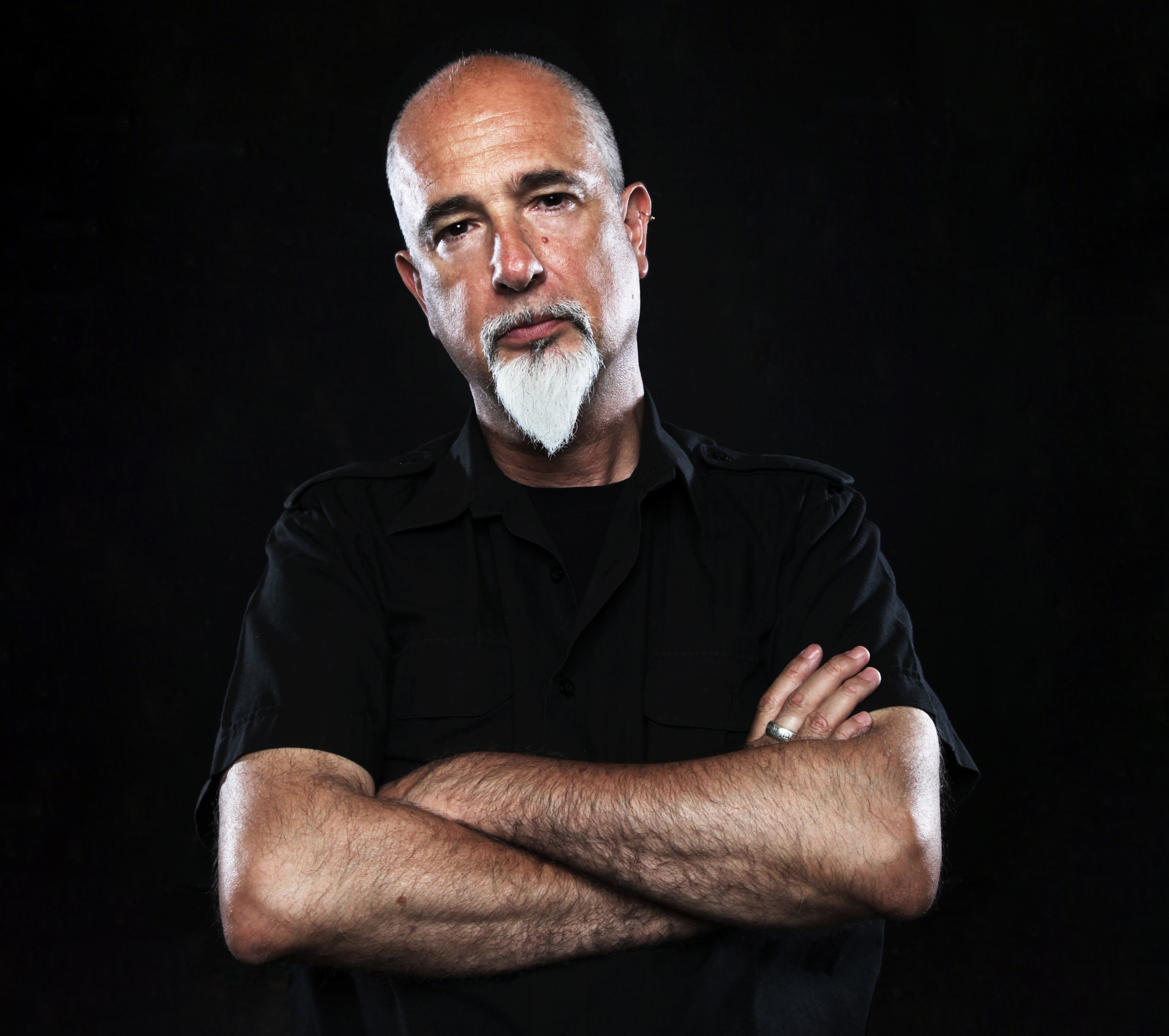

Eraldo Bernocchi

The Beauty of Broken Things

by Anil Prasad

Copyright © 2023 Anil Prasad.

Photo: Michele Turriani

Photo: Michele Turriani

Eraldo Bernocchi’s shapeshifting output has quietly influenced countless musicians across the world. The Italian producer and multi-instrumentalist has appeared on hundreds of releases since his professional career began in 1985. More than four dozen albums, EPs, and singles feature his name on the cover, with the rest of his recordings illustrating his focus as a serial collaborator.

Based in London, Bernocchi’s oeuvre is impossible to categorize. The musician has explored countless genres, with many projects blurring the lines between them. Experimental, ambient, dub, rock, noise, and minimalism, are a few of the realms he’s known to embrace. His recombinant approach also manifests itself in a great deal of film, television, advertising, and installation soundtracks.

Bernocchi has worked with some of the most renowned artists imaginable. And often, he’s the catalyst in spurring partnerships with them to life. Harold Budd, Iggor Cavalera, DJ Disk, DJ Olive, Colin Edwin, Gaudi, Robin Guthrie, Mick Harris, Toshinori Kondo, Bill Laswell, Russell Mills, Nils Petter Molvær, and Markus Stockhausen represent a fraction of the musicians he’s recorded or performed with.

In addition to his activities as a creator, in 2008, he co-founded RareNoise Records, together with Giacomo Bruzzo. The label has released many Bernocchi-related albums, as well as dozens by others, such as Buckethead, Marilyn Mazur, O.R.k., Bobby Previte, Jamie Saft, J. Peter Schwalm, Stephan Thelen, and Cuong Vu.

Bernocchi was incredibly prolific just ahead of and during the COVID-19 pandemic between 2019 and 2022. He completed no less than eight albums during those years. They reflect his wide-ranging interests, not to mention his reality-based perspectives on our species. He’s unafraid to use his music to communicate his cynicism and scorn towards global political and religious establishments. There’s also optimism and beauty in some of his music, particularly focused on the achievements and ideas of those with anti-authoritarian proclivities.

His recent ventures include two 2021 albums with his longest-running ensemble, Sigillum S: Coalescence of Time and Blues and Doped Flowers from Twenty Three Years After Eschaton. The latter was co-created with the Italian experimental group Macelleria Mobile Di Mezzanotte. Both releases offer myriad cross-genre compositional constructs, with lots of processing, treatments, and occultist elements.

Patterns and Mechanisms, his 2022 release with Merzbow is, unsurprisingly, a noise-based project, but one tempered with arrangements and structure. It’s designed to communicate how the animal kingdom and humanity have begun intersecting in curious and not always comfortable ways.

In 2019, Bernocchi put out Of Flies, under the name Blackwood, which examines his darkest impulses even more deeply. The solo project is a vehicle for questioning humanity’s choices that work against its own best interests. Musically, it’s a descent into an ominous realm where distorted baritone guitars, sub-bass, slow rhythms, and treated, sampled vocals are core currencies.

SIMM, Bernocchi’s beat and bass-focused project, released Too Late to Dream in 2021. The collective goes back to the mid-‘90s with a historically instrumental focus. But for its current effort, it took a turn into the hip-hop universe with the addition of MC Flowdan, who articulates methods and motivation for pushing back against corporate and political hegemony.

The theme of societal decay is further evoked in Broken Masses, his 2022 duo LP with Ramleh and Breathless guitarist Gary Mundy. Entirely derived from processed guitar performances, the album evokes the fear and frustration humanity faced during the pandemic, as well as the long-term aftereffects.

Bernocchi’s most melodic output can be found in two recordings he’s made with Tangerine Dream violinist Hoshiko Yamane: 2021’s Mujo and 2023’s forthcoming Sabi. The music is focused on percolating electronic compositions and serene soundscapes. For Bernocchi, the meditative and contemplative nature of his work with Yamane represents another approach towards activating societal change.

Bernocchi discussed all of these recordings in detail with Innerviews. He also delved into his beginnings as a musician and other key collaborations that have informed his singular path.

You were incredibly productive during the COVID-19 pandemic. Describe what life was like for you during it.

I'm a little bit ashamed to admit that it was a good period, because for the first time in my life, I had so much time to think about music. I was free without schedules, the pondering of project delivery, or the timeframe of things. Of course, it was also a scary period, especially at the beginning, but after a while I got used to being at home.

The good thing is that the UK government helped a lot of self-employed people. We got money from it for nearly two years. So, I was able to focus on pure creativity. Most musicians were in the same situation, although many had money worries. Nobody was recording together in studios or touring. As a musician, I had the chance to contact people and do things that otherwise would have been more difficult.

The pandemic also left behind a very weird situation. The number of gigs is reduced compared to before COVID-19. I also used to rely on a good part of my income from music for adverts. That market changed a lot, because nobody was shooting adverts. Everybody was using social networks for advertising during the pandemic. There was the realization that perhaps that was more useful than the usual TV and cinema approaches for promotion. This reduced work for a lot of musicians.

Photo: Michele Turriani

Photo: Michele Turriani

Tell me about the creative process that enables you to be so prolific.

It’s just something that’s always happening, and I can’t stop it. I think I will go on like this until the day I die. I want to constantly research and explore new sound fields. I think that explains why there are a lot of genres that I’ve crossed. Some with good results, some with decent results, and others with horrible results.

It's not up to me to judge my work, but it's something that comes from ideas or concepts. For example, I’ll have an idea like “I want to record electromagnetic fields in sacred places and then use the recordings as the foundation for the next Sigillum S album." Those concepts can be the raw material for a project. It’s all about my love for sounds that inspire me. Everything I do is emotionally triggered. I’m not someone who says “Yeah, now I’m going to do a jazzy thing.” I’m self-taught and don’t have the music theory or academic background that enables me to do that, anyway. I can’t write a bossa nova piece from a theory point of view.

I also don’t work in a linear way. I may have a few hours in the studio when nothing is happening, and then I’ll have an idea for bass and the beat. If I like it, I might say “Where is this going? It could be a SIMM beat.” So, I’ll put that in a folder, and it may remain there for years. In the case of SIMM, it might be many years.

Things can work in other ways, too. For instance, it’s very natural for me to work with Hoshiko Yamane. I’ve always been able to work well with Japanese musicians. There’s some kind of connection I have with them. With Hoshiko, we have a mutual exchange of ideas that’s very rapid. Same with Gaudi, who I’ve been friends with for 30 years. We’ve established a common language that makes creativity an easy process.

So, there can be an immediate collaborative approach, or it can be a case of something lingering for years. For me, it’s all about finding the right moment and following my inspiration.

Let’s explore your recent projects, starting with Patterns and Mechanisms with Merzbow and Sabi with Hoshiko Yamane. But before that, it’s fascinating that you could be involved in two such radically different types of music. Talk about your interest in working in both totally melodic and noise-based contexts.

It probably has to do with my background when I was younger. I started as a musician when I was 13, when punk emerged. I was a punk and metal guitarist, but this always felt a bit reductive for me. When I was rehearsing with the bands I had at the time, it was deadly boring, because we were always playing the same songs and I wanted to change things up, improvise, and explore other stuff.

I was already creating a little bit of a problem for my punk and metal groups, because I was listening to everything, including Pink Floyd, Ash Ra Temple, Tangerine Dream, Black Sabbath, Led Zeppelin, Genesis with Peter Gabriel, and Throbbing Gristle. And then hip-hop came along and I was totally into that, and still am.

It became very easy for me to move from one musical point to another as a musician, because I always did it as a listener. I created Sigillum S to have total freedom. If you listen to music from across the Sigillum S discography, you have noise, drone, ambient, industrial, musique concrète, and rhythmic albums.

Explore how you first engaged Merzbow, and the way Patterns and Mechanisms came together.

We have some common friends. I was talking with Balázs Pándi, the former Obake and Metallic Taste of Blood drummer. I said, "I’d really like to do something with Masami Akita." They played together, and so Balázs sent him an email on my behalf, and Masami said "Yeah, let's do it as long as it is not controversial." He's very strict about these things. He’s a militant vegan and he doesn't like anything to do with his past when Merzbow was more extreme, with the whole BDSM thing and beginning of the industrial movement.

I was fine with that and came up with a concept which I submitted to him, about patterns and mechanisms. Basically, the album is based on the migrations of animals that are colonizing our cities. As we shrink their habitats, they are slowly moving into our cities, and they are able to recreate their own environment there. That's very interesting to me. For instance, here in London where I live, there are three foxes living nearby and they’re part of the street. People even give them food.

Masami liked the concept and sent me two sessions that were precisely 20-minutes long, which was great because we were thinking about vinyl for it.

I wanted to work within a more musical approach, instead of going for a pure barrier of noise, which is Masami’s unique and incredible trademark. I worked on powerful sounds but wanted it to come together as real arrangements. The idea was to create two suites with a bigger sound than more extreme music, in which the sound is typically so compressed. My sound needs to be fat, even if it’s ambient.

What’s your perspective on what noise music reflects in terms of the human condition?

I think it reflects change. I was part of the mid-‘80s noise and industrial scene—the early period. For me, that’s the only industrial scene. The rest is electronic music. Nine Inch Nails is not industrial in my opinion.

I think noise music is a further development of punk. When I played punk, I was totally in love with The Sex Pistols and other bands from that period. Then hardcore came along, and I thought “Okay, this is really what I need.” And then Discharge emerged and I said “Okay, that really is it. End of story.” But then I discovered noise and felt it was a further step beyond punk, while retaining its immediacy. Noise is right in your face and it’s very effective.

I think noise emerged because society changed. I think we were doing certain things in the ‘80s with the intention of being in opposition to the mainstream or just shocking people in the audience. The idea was to disturb thought processes the same way someone might dislocate their shoulder or by being hit by a van coming at you 100 miles an hour. [laughs] The idea was to communicate the pain of current society and our refusal to go along with certain ways of thinking.

The underground scene was really word of mouth back then, whereas now it’s all online and involves people exchanging files. But to me, it’ll always be about the punk thing and refusing to bow down to people you disagree with.

I look at Mick Harris as one of the most extreme punks that is still around from that era. Mick’s Scorn project became slower, heavier, and more distorted as time went on. It became less and less musical, and more evil and twisted—like only Mick can be, but the attitude is still punk to me.

Eraldo Bernocchi and Hoshiko Yamane | Photo: Ari Matsuoko

Eraldo Bernocchi and Hoshiko Yamane | Photo: Ari Matsuoko

Discuss your ongoing collaboration with Hoshiko Yamane and the approach you took for the Sabi and Mujo albums.

I connected with Hoshiko when we both played the Extreme Chill Festival in Iceland in 2019. She was there with Tangerine Dream and also playing in a duo with the Swedish pianist Mikael Lind. I gave her one of my records and she liked it. We spent a couple of afternoons talking about my love of Japanese culture and her approach to music.

When I saw her perform, I felt I could do something with her, because she is a violinist with a classical education and plays in contemporary orchestras, which is very difficult, but also treats the violin with electronics, as well as uses synths and machines. I felt she was open-minded.

During lockdown, we started to work on music. We were both at home exchanging many tracks. We found an approach that worked for us. I was a little daring on my side in that I decided to use a single machine for Mujo, the first album we did back in 2020. Creating limits can generate interesting results. So, I chose to focus on using the Elektron Analog Four MKII, which is a four-track monophonic synthesizer. The synth is an endless machine that sounds amazingly good. It has two oscillators and sub-oscillators. So, each note can be a chord.

I thought “Okay, I want to force myself to work with this machine and use only four tracks.” So, Mujo is mostly me on that instrument, along with a sub-kick I added to a couple of tracks. Hoshiko sent me a lot of layers for the tracks. It’s like a landscape of emotions. And that’s how that album came together.

When it came time to do our latest album Sabi, we went with the same concept, because it worked so well previously. The idea of us both being minimal and working on shades of things was great. I added a couple of other things, but conceptually it’s another step from the impermanence of Mujo.

Sabi is about the beauty of broken things in Japan. In Japan, they have an ancient tradition of repairing things. If you break something in a kitchen, like a bowl, they’ll repair it. And they tend to repair it with gold. So, this broken thing becomes beautiful and shining. It’s a very Japanese concept they apply to daily life.

Hoshiko named the album Sabi. She said it was the word that summarized the concept. It captures and condenses the idea perfectly.

Let’s look at the making of Sigillum S’ two 2021 releases, Coalescence of Time and Blues and Doped Flowers From Twenty Three Years After Eschaton, both of which feature cross-genre compositional constructs.

Years ago, we decided to do a rhythmic album. Bruno Dorella is a recent collaborator in Sigillum S, because Luca Di Giorgio wasn’t available to work on it, though we’re still in touch. Bruno was a fan and does some great, extreme experimental metal music. So, he entered the picture in 2016 and is a very solid drummer that’s incredibly precise and minimal.

So, Bruno, Paolo Bandera, and I went into a studio in London to make Coalescence of Time. Bruno went for beats, and we improvised. I had a sampler and an Elektron Octatrack, and Paolo had his noise machines. Bruno recorded some acoustic drums, but it wasn’t satisfying for this context. So, I treated everything he did to an extent that his drums are unrecognizable. They’re recombined and filtered.

Paolo is the person behind the main Sigillum S concepts. He’s critical to how the pieces are put together. But they reflect the decades of life we’ve experienced and the fact that time is just the flickering of experience and suspension of things to focus on the creative process and outcome.

Putting out a record, if you think about it, is akin to making an eternal statement, because especially now, in the digital world, it’ll be there forever. I’ve found things of mine on YouTube that are very old and obscure. I’ve wondered who put them there. YouTube says they’re sometimes automatically added. All of that reflects the coalescence of time and how it moves yet stays still. It’s a very strange sensation that’s fascinating.

Blues and Doped Flowers From Twenty Three Years After Eschaton is an album we did together with Macelleria Mobile Di Mezzanotte. We’ve known them a long time. Their music kind of borders the soundtrack field, as well as a dark melancholy I find fascinating. During the pandemic, we had the idea of trying to make something together. They sent us horn parts and parts of compositions, and we added the rest. I then arranged it into two long tracks. I like the album. It would be nice to hear the music synced to a film.

Sigillum S: Paolo Bandera, Eraldo Bernocchi, and Bruno Dorella | Photo: Stefano Masselli

Sigillum S: Paolo Bandera, Eraldo Bernocchi, and Bruno Dorella | Photo: Stefano Masselli

Sigillum S has been going since 1985. Talk about the initial vision and how it evolved.

The beginning was very simple. All of the people connected with Sigillum S would go buy records every Saturday in the same shop in Milan. I put a typical sign up in the store with those little phone number cut outs on the bottom. It said, “I’m looking for someone who wants to go into new territory.” For two weeks, the pieces of paper remained. Nobody took one. Then, suddenly, one guy called me up and it was Paolo Bandera. He said, “I have the same concept you have.” And that concept was to create an anti-band—the opposite of a band. We wanted to be an open collective of creative people using any kind of media available. The thought was to create music, images, and performances without any restrictions.

Luca Di Giorgio lived 50 meters from my place. He was younger than us, but we’d always go to concerts together. So, it was a natural thing for him to be involved. I was a guitar player, but more of a noise maker. Paolo was a bass player and noise maker, too. Luca had a solid classical music piano background. He plays Ravel, Debussy or Messiaen for pleasure. He really can play.

When we first got together, we thought “What do we call this?” All of us were into Austin Osman Spare, Aleister Crowley, and the occult side of things. I came out with this idea of Sigillum, which comes from Sigillum Dei, the seal of God. The initial idea was to change the letter at the end. So, for instance, when we started as Sigillum S, the S referred to “sanctum,” from “holy” in Latin, and "Satanicum," from Satan. So, the S had two different meanings. We liked to play with the two meanings.

Then we thought, we could also use Sigillum N for a noise project. The idea was to change the letter according to the project, but that never happened. In the end, I started to study more and got into the Enochian alphabet from John Dee, which is an occult constructed language, and in it, the letter S is connected to angelic conversations and calls. So, we said “Let’s keep it as S” because it relates to everything.

Because it was an anti-band, the lineups kept changing, except for Luca, Paolo, and me. I would also say from 1993 onwards, Petulia Mattioli, the graphic designer and video artist, has been the fourth member. She’s the one behind all the live videos and covers—the image centralization of the whole thing.

Ultimately, Sigillum S relates to the fact that I’ve always collaborated with loads of people. I believe very strongly in exchanging creativity. It’s also a political statement about occultist noise, which was divided in the group. Paolo is the noisiest of us all. I’m more into the ritual side of things. Bruno is the one who evens the peaks.

Sigillum S is also derived from what Austin Osman Spare discussed in terms of creating tools for your own rituals. He took Crowley one step further in emphasizing the simplification of your inner self, and the power he referred to as exhaust—a decision system he conceived. He believed everybody could create rituals without the infrastructure of the occult thing.

It might sound weird to say it, but Sigillum S exhibits a punk attitude even within the occult side of things. We are all about challenging preconceptions and creating individual tools for rituals that can be applied to anything, even dinner with friends, a crazy dance party, or sex.

SIMM’s Too Late to Dream was sparked into life by a new drum machine you were fascinated with. Discuss the reemergence of SIMM, and the inclusion of hip-hop elements with provocative lyrics.

SIMM is a very personal project. It’s like taking photographs from my window. It goes back to what I said about having ideas and putting them in folders. I had been storing up ideas and one day I had a feeling it was time for a SIMM album. When the time came, Elektron gave me an endorsement and gave me some gear, including an Analog Rytm MKII, one of the new drum machines they released. I thought it was very interesting what could be done with it. I started to lay down lots of beats and realized this could be the backbone of a new SIMM project.

I put together a new team for SIMM during lockdown. I sent some ideas to Kurt Glück from Ohm Resistance, and he was totally into them. Then I contacted Flowdan, because I wanted to include an advanced MC presence on it. Flowdan is incredibly gifted with a low and booming voice. He’s one of those lyricists who writes amazing, poetic, and evocative sentences.

I also contacted Phelimuncasi to do a track. Phelimuncasi’s vocals were so powerful, that I killed the original SIMM track I had with them in mind and built a totally new one to support their approach. They’re so incredibly energetic. I’m very happy with how this album came out.

You also have a recent soundscape recording with Gary Mundy called Broken Masses. Explore the societal context the album captures and the music that resulted from it.

Gary first contacted us in Sigillum S in the ‘80s to put out a cassette album called Trance Flexure on his Broken Flag label. So, we’ve been friends for almost 40 years. He’s also the guitarist for Ramleh and Breathless, which is one of my favorite bands. We’ve always said, “We should do something, but only with guitars.” We finally decided to go into the studio with guitars and pedals just for the sake of it. We recorded these really long sessions that you could call soundtracks for daily life. The whole thing happened right after the second lockdown, when things were starting to relax a little bit.

Gary came up with the title Broken Masses, which I thought was perfect. It’s how the whole planet was feeling during lockdown. COVID-19 broke society. We saw the system crumble to pieces before us. It also planted the seeds for something similar to happen in the future when someone wants to slowly change our approaches to life. In that way, Broken Masses can also refer to religion.

Petulia Mattioli came up with a cover I liked a lot. It’s a photo from Bangkok of the Sathorn Unique Tower. I’ve visited this building countless times, because I was working in Thailand a lot in the late ‘80s. Basically, this building was supposed to be an amazing condominium tower for the wealthy. Then an economic crisis occurred, and they never finished it. So, it’s a ghost building. Nobody has the money to tear it to pieces. So, it remains and it’s a gathering point for junkies, small-time criminals, stray dogs, and people who kill themselves by throwing themselves off the edge. It’s also full of weird drawings and endless graffiti.

People aren’t supposed to go inside, but they do anyway. If you give someone $5 you can easily go in, but it’s very dangerous because it’s crumbling into pieces and is very tall. You’ll get vertigo if you’re up there. But it’s a perfect metaphor for Broken Masses.

Photo: Francesco Filippo

Photo: Francesco Filippo

Blackwood, which is essentially a solo project, is steeped in cynicism and examines humanity’s darkest impulses. Provide your thoughts on the motivation behind the music.

It started because I couldn’t find anyone who could create this kind of music with me. I typically find working by myself boring, but the Blackwood sound meant I was going to be mostly on my own. It’s me at my darkest. It’s my most depressing work.

For instance, “Breaking God's Spine” is an example of me thinking about symbols I can’t stand. I’m Italian and grew up in a Catholic country in which the church still has a lot of power. A pope died recently and people lined up by the thousands to pay homage to someone who buried his head in the sand. There are so many pedophiles and so much corruption in the church, and yet people praise him. I consider that unacceptable. Blackwood is about my darkness in considering that. It’s almost like me trying to combat that stuff.

The name comes from a place I imagined called Blackwood. It’s where all the dreams of people go to die. So, when you have a wish and it doesn’t come through, it goes to Blackwood, where there are creatures that keep them under lock and key. The wishes and dreams never leave the place.

Musically, I wanted to create something really overwhelming that pressures the listener. So, I mostly used baritone guitars that are tuned down one octave. I spent forever trying to find the sound I wanted, because when you tune down, you lose a lot of upper harmonics, and everything tends to sound muddy. I wanted the sound to be massive, not muddy. So, it was a long journey to find the right baritone sound and I did.

I eventually involved two women vocalists in Blackwood: Emilia Moncayo from Minipony and Stefania Alos Pedretti from OVO. Emilia is an incredibly diverse singer and Stefania is very unique as a metal vocalist. But it’s still mostly instrumental music with a lot of ambient elements.

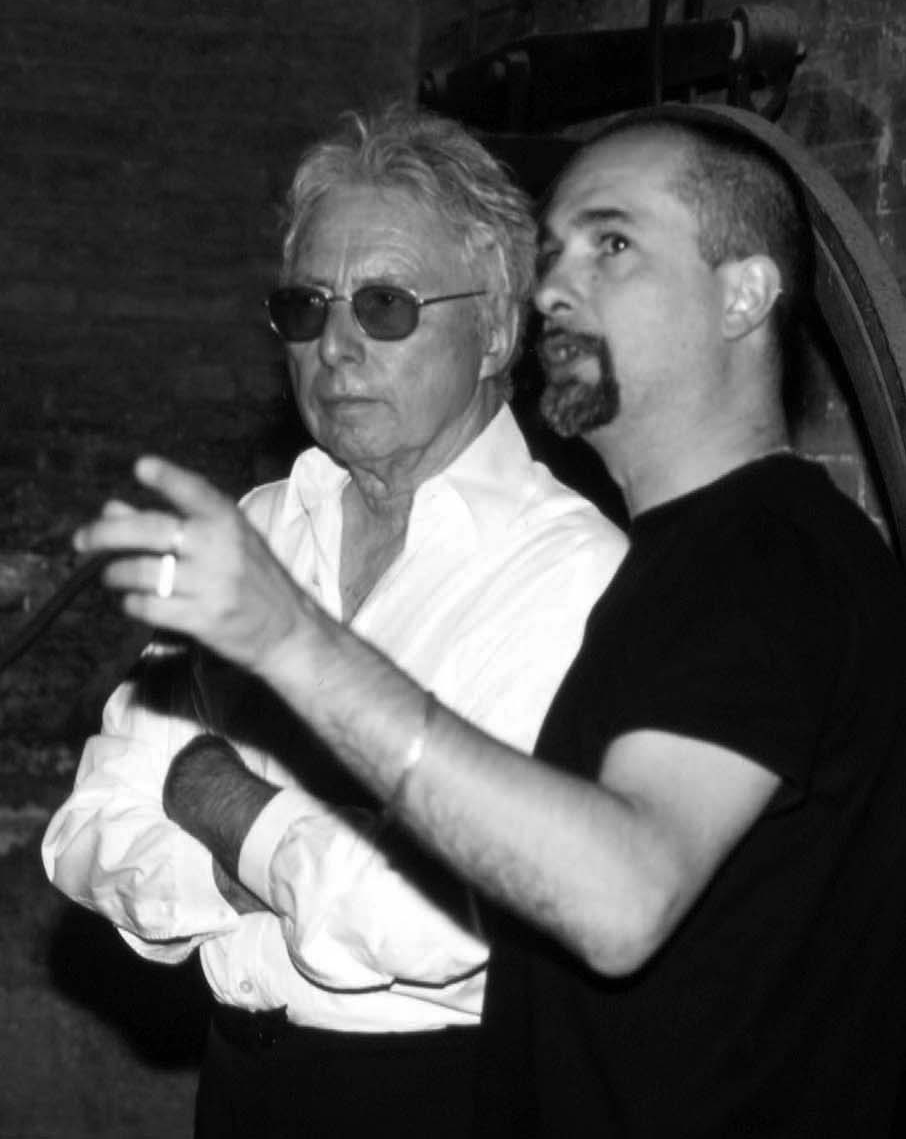

Harold Budd and Eraldo Bernocchi, 2010 | Photo: Paolo Emilio Sfriso

Harold Budd and Eraldo Bernocchi, 2010 | Photo: Paolo Emilio Sfriso

Reflect on the work you created with Harold Budd, including 2005’s Music for ‘Fragments from the Inside,’ and 2011’s Winter Garden, together with Robin Guthrie.

Working with Harold was one of the most pleasurable things I can remember. I was a little scared to work with him before I met him, because he was one of my idols. It was one of my dreams to collaborate with him. We got in touch in 1995. I wrote him a letter, and nothing happened for four months. Then one day, I received a letter from Harold. It was six pages, written out perfectly with impeccable grammar. We started to exchange ideas and concepts, but then he went into one of his phases when he said, “I’m leaving music behind.” So, nothing came of those conversations at first.

Time passed and I received a request from a museum director in Italy proposing I work on a soundtrack for a video installation by Petulia Mattioli. I agreed and got a decent budget for it. I proposed I do it with Harold, which the director loved. Harold agreed to do it, and it’s what the Music for ‘Fragments from the Inside’ release captures. It’s a completely unedited live concert, except for one minute I cut out for space reasons.

When working on the project, I prepared various ideas ahead of time for Harold and he chose five to work on. I said, “Let’s rehearse them.” Harold replied, “Rehearse? Why? Let’s just find the keys.” So, we did. We wrote down a few things and composed in real time. That’s the approach I always had, but I didn’t expect him to work the same way. It was like being in a dream for 90 minutes. I floated through it with him.

Winter Garden was different as an approach. It was made six years later. Harold and I had decided to make another record. We also managed to get two gigs in Genoa and Milan for when he visited me in Italy. Harold then said, “Is it okay if we involve Robin Guthrie?” Of course, I said “Absolutely, yes.” I’ve got everything Cocteau Twins did and many of Robin’s records. We went into the studio for three days and it was super easy.

I remember two episodes from those sessions that were interesting. Robin and I were improvising on something, and at a certain moment, we went into a harmonic change, and we loved it. Harold heard it and said, “Whoa. Stop everything. This is horrible.” We were like “What?” He said, “This is gospel music and I can’t stand gospel music.” The funny thing is Robin is self-taught like me. So, he looked at me and we looked at Harold and said “We have no idea from an academic point of view what that means. What the hell is gospel music? But okay, don’t worry, we won’t go there again.”

Another time, I was playing Harold an electric piano theme I had in mind. It was very simple. I said, “I’ve got these six notes and two chords, but it’s really your field. I like how they sound, but maybe you can work on them further.” He looked at me and said, “No, what you’re going to do is play electric piano. And I’m going to play acoustic piano.” I was really scared and worried, because our instruments were facing one another. So, here I am playing piano with Harold, though I am not a piano player or even a keyboard player. I’m a self-taught sound maker. If I need someone to play serious piano, I ask someone else. So, with Harold, the situation for me was “Oh god, what’s going to happen now?” But we did two takes and it went really well. He was super-happy. He said, “See? That came out great.” And one of the pieces ended up on the record. So, it was really a blissful thing to work with him.

Two months before Harold died in 2020, we were exchanging emails. I really wanted to do another record with him. He said “I have some serious health problems, so I can’t really play the piano anymore. I’m playing other things and mostly composing for strings. “I said “Well, we can think about working within that. We could also rework some of the tracks we did for Winter Garden, because we’ve got many tracks we didn’t use.” Harold said “No, that’s the past and it stays in the past.” So, those will never see the light of day. We didn’t get to do another record, but I’ll always be grateful for the opportunity to collaborate with him. Harold remains in my heart.

Eraldo Bernocchi and Bill Laswell, New York City, 2005 | Photo: Petulia Mattioli

Eraldo Bernocchi and Bill Laswell, New York City, 2005 | Photo: Petulia Mattioli

You’ve worked extensively with Bill Laswell. Give me a big picture view on what you’ve accomplished together.

I consider Bill my artistic father in a way. He’s a towering figure for thousands and thousands of musicians. He travels from planet to planet when it comes to sound. He’s never been afraid of playing with any kind of musician, from extreme metal to ambient to drone to jazz to funk to rock to you name it.

I’m very proud of the Somma project we did with Tibetan monks and many musicians. I’m also very happy with the first Charged album we did with Toshinori Kondo in 1999. It has stood the test of time.

The same goes for the Ashes album Corpus from 1996. It was the second time we worked together, and he gave me a lesson in the studio on space and its critical necessity in the architectural elements of a track.

I remember, I came to the sessions with my guitars and samples. The engineer Bob Musso opened all the channels and we worked on vocals. When it started to happen, Bill said “I love this stuff, but do we need this pingy sound on it?” At the beginning, I was like “Fuck that! I love my pingy sound. I conceived that pingy sound there.” [laughs] Bill said, “Let’s try to mute it.” And he did that on one-third of the things I brought in. And then suddenly everything blossomed. Less was more. It was an incredible lesson. It taught me how to get rid of redundant elements and effects.

We’ve also played live together many times. Bill is able to work within any kind of music in performance, too. He’s a master. He’s also someone that’s created sound tools for rituals. His vision of music is ritual. I’ve also seen him countless times live without me involved, and every time has been mind-blowing. He’s always doing unexpected things.

You're currently collaborating with Iggor Cavalera. What can listeners expect from the partnership?

I'm a massive fan of Sepultura, as well as Soulfly and Cavalera Conspiracy. Iggor lives in London, and we’ve met a couple of times. He's also into electronics, and his live solo sets are really great. We started to jam and, in the end, decided to create a project. We’re working on it, keeping four concepts in mind.

The first is “limitation is liberation.” By mainly using two twin machines—the Erica Synths Perkons HD01—and our own creativity, we’re forcing ourselves to work within strict constraints, inspiring us to find new ways of using the instrument and resulting in a more focused and cohesive project.

The second is “the atavism of ritual.” Session after session, we discovered that the project is leaning towards a ritual-like concept. So, we chose to work on sonic landscapes that are greater than the sum of their parts, in which we’re drawing on each other's strengths and expertise to create music that will be judged by the emotions it evokes in listeners, but also hints at deeper and ancient meanings, often forgotten through the mist of history.

Next is “repetition is power.” Through the wordless magic of constantly increasing intensity, we discovered hidden images appearing across the sound structures, merging themselves more and more into muscles and brains, like contemporary versions of forgotten tattoos.

Lastly, there’s “the sweat of eternity." By adding huge beats and derailed drones on each other, we then grinned like beastly gods and flew into a physical state without boundaries, forgetting ourselves in a drenched mix of unholy symbols and pure liquids.

We’re hoping to complete an album later this year.

We also started a new trio together with Dwid Hellion, the legendary singer from the hardcore metal band Integrity. Dwid is a monster of a singer. His voice is deep and raspy. He has a project called Psywarfare that is super-violent, so we are totally navigating the same seas. It’s a very good gathering of minds. Iggor and myself are on electronics, and Iggor is sometimes on drums. Dwid is blasting with his incredible voice. It’s a mixture of noise, super-fast metal and various creepy and strange sounds. I don't know how to define what we are creating, and that's good. We are recording various tracks these days. They're short, impactful, and direct.

You believe all sounds are an extension of spirituality. Expand on that idea.

My family is Catholic. They don’t practice, except during Christmas and Easter. I’ve been baptized and went through communion and confirmation. But I stopped believing in it when I was 13. I looked around and said “Well, fuck that. You’re preaching and teaching certain things and behaving in the opposite manner. This is not working.”

So, I got more and more into other things. I was really sucked into the Tibetan Buddhist approach. I could have been a Buddhist, but it’s a little limiting for me. However, there’s a structure within it that absolutely adheres to my thinking.

What also interested me in it is that there's a very thin line between Tibetan Buddhism and the Bone Shaman system, which relates to the idea that sound and noise have a spiritual connection to the natural world. I believe more in a tree than I do in religion. There's a form of energy there. You can call it a spirit. You can call it the god of the tree. But it’s very spiritual. This extends to paying homage to other plants, animals, waterfalls, mountains, and so many other entities.

We live on one planet, but there are different planes of reality on it and beyond it. This also relates to quantum physics and different dimensions. Time is moving at different speeds and going in different directions in various dimensions.

I don’t know if there’s a god. But I tend to think, if there is a god, he’s a cruel being. He’s not the one we’ve been sold. I think about the ever-loving god I was told about as a child—the one that cares for all creatures. Look outside your window and see how he’s caring. There’s something that is not matching up. I don’t like to think about a celestial being caring for me or punishing me. I have an approach that is much more shamanic, and it explains my interest in the occult and occult noise. That’s why I’m interested in things like recording magnetic fields from temples or cemeteries in Japan.

The Sufi point of view is that sound is the beginning and end of everything. So, one can say sound is a manifestation of something higher. Think about it. You cannot see sound, but you can feel it physically as you hear it. For instance, if you go to Iceland, the wind can be so strong that you hear it and also feel it on your chest. To me, that’s a manifestation of how sounds reflect a connection to something that’s far bigger than us and beyond conventional ways of thinking.