Donate to Innerviews

Since 1994, Innerviews has provided uncompromising, in-depth interviews with musicians across every genre imaginable. And it does that with no trackers, cookies, clickbait, or advertising.

Your donations are welcome to help continue its mission of highlighting incredible music and artists, without any commercial considerations.

Your contributions will be instantly transformed into stories and videos, and cover hosting and web management costs. Importantly, your dollars will help ensure Innerviews remains absolutely free to all visitors, independent of their ability to financially support it.

Please consider making a donation today by using the PayPal QR code below.

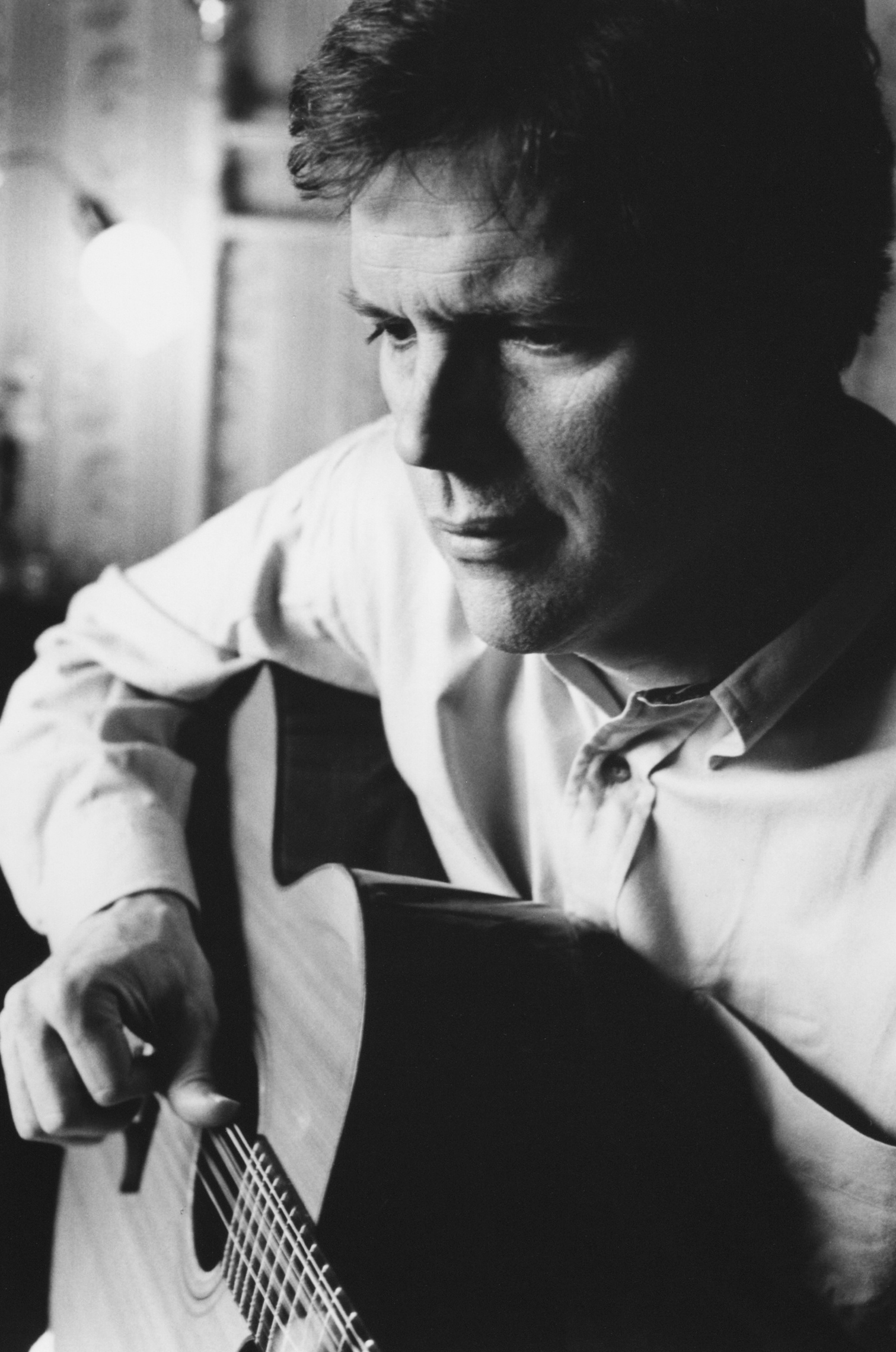

Leo Kottke

Choice Reflections

by Anil Prasad

Copyright © 1999 Anil Prasad.

Photo: Private Music

Photo: Private Music

Leo Kottke continues to blaze his own trail, 33 years after beginning a peerless career that established steel-string, fingerstyle guitar instrumentals as a form of pop culture. His deep and influential discography numbering 20 albums, along with his status as one of the world's most resilient, prolific touring artists, have ensured an enduring place in the hearts and minds of listeners and musicians across genres and demographics.

Though predominantly known as a solo live performer, the '80s and '90s saw him release several collaborative releases, including 1994’s Peculiaroso and 1997’s Standing in My Shoes.

Peculiaroso is a relaxed, humorous and meditative effort produced by Rickie Lee Jones. It also features electric guitarist Dean Parks, accordionist Van Dyke Parks, bassist John Leftwich, drummer Bill Berg, and Jones and Syd Straw on vocals.

In contrast, Standing in My Shoes, produced by David Z, situated Kottke’s guitar work and vocals within a modern rhythmic context. The playful recording is infused with funk and hip-hop arrangements, and creative electronic programming. It also finds him reimagining several classic pieces, including “Vaseline Machine Gun,” “Corrina, Corrina” and “Cripple Creek.”

In 1999, he went back to his roots with the release of One Guitar, No Vocals. The album is a beautiful, mercurial collection that highlights his instrumental mastery. It’s notable for the inclusion of the three-part, nine-minute “Bigger Situation," one of his most ambitious and complex compositions to date.

Kottke’s artistic and commercial success has inspired generations of musicians to explore acoustic guitar. Perhaps the most important artist he spurred to action was fellow guitar visionary Michael Hedges. While many compared and contrasted the two, the fact is they were great friends and collaborators.

“Leo is a true example of a composer writing on the guitar,” said Hedges, who passed away in a 1997 car accident. “He’s got so much soul, but he’s also got so much rhythmic drive. He’s a real groovemaster. You just can’t beat him and you’d never want to. You just want to listen. He’s got so much integrity and depth, and he’s truly a sweet man.”

Tell me what the album title Peculiaroso means to you.

As my first manager would say about all my titles, “It doesn’t mean anything.” On the other hand, it does have a lot of resonance for me. I think it’s true as a one-word description of what we see when we open our eyes. Things are pretty peculiar out there. No matter how wise we think we are, things are always contrary to expectations. What’s really peculiar is the fact that we’re continually surprised by the way things are. I go around saying “Huh?” and “Wow!” and “I think I’ll go hang myself in the closet.” That feeling doesn’t happen very often, but that surprise comes along too. It’s just a bad day when it’s all a mess and you’d rather be dead. I’ve met people who claim to have never had that thought or got that down and they worry me. If you never feel that way, you’re going to sooner or later. If you’ve had no experience with it, you might think that’s what you should actually do as opposed to something you might want to do.

During his early twenties, the pianist Arthur Rubinstein was having a hard time getting gigs and during the gigs he could get at that time, he’d forget his repertoire. He hit a real low point and went into his closet and hung himself with his necktie. The necktie broke and he hit the floor and started to laugh and that guy didn’t stop laughing. But he knew it wasn’t a joke. He was happy to be alive. You can hear it when he plays.

Leo Kottke (lower far left) at U.S. Navy submarine school, New London, Connecticut, 1964 | Photo courtesy of Jack Deschene

Leo Kottke (lower far left) at U.S. Navy submarine school, New London, Connecticut, 1964 | Photo courtesy of Jack Deschene

“World Made to Order” from Peculiaroso reflects on your Navy stint in 1964 serving on a submarine with an engineman whose nickname was “Evil.” Tell me about those days.

Evil’s nickname wasn’t so much for being a bad guy, although I did see him stab a guy in the neck with a fork once. It was for the way he looked. He just looked evil. Engine rooms were pretty dark and they smell like diesel oil and Evil looked like he’d been born there. He was a grim sight. He drank torpedo fuel. It wasn’t an uncommon practice. There are a lot of things that have more alcohol content than booze. Torpedo fuel didn’t have more alcohol, but it wasn’t illegal to have on the submarine. So, Evil would smuggle a few loaves of French bread to use as filters and have a cocktail now and then. For those people who did drink it—and I was not one of them—they called it a “Pink Lady.” It was horrible. No-one ever accused the Navy of having a gift for metaphor.

My Navy days were short. I was only in it for seven months. I went to sub school in New London and then was put on a boat called the USS Halfbeak. We mainly cruised up and down the Northeast, around Newfoundland. I hated the Navy. I didn’t function well in that environment. I put our sub out of control once on a dive. I nearly killed us all. I was on the stern planes and I didn’t know what I was doing and I put the boat into a 20-degree angle on the dive. Ten degrees is out of control. We were plummeting below crush depth. They did something called “blowing the saddle tank” which is a last-minute, desperate measure, because lots of times when you blow the saddle tank, the boat flips upside down and you sink like a stone anyhow. But we lucked out. On the mental stability questionnaire you fill out to see if you’re fit for service, they didn’t ask “Have you ever wanted to hang yourself in the closet with a necktie?” If they did, maybe they wouldn’t have let me in.

How do you go about channeling tales like those into instrumental pieces?

Ninety percent of the time, the tune just comes along as you’re writing it. An idea or a memory will pop into your head and they don’t come from nowhere. They really are introduced by the piece you’re working on. That’s what the tune is. It’s something that has an analog in whatever it is that crossed your mind, like these little sketches that my brain registers. You just kind of segment your timestream and there it is. I think our brains do it automatically. People have different triggers for that. For me, it’s guitar tunes. For others, it’s things like scotch or friendship.

Does that hold true for when you’re writing lyrics, too?

The same thing happens. Your brain is off, but you’re paying attention. You don’t get to direct how it happens. In that sense, it is stream-of-consciousness, but it’s not just about transcribing the noise in your head. I’m pretty deliberate about it. Every now and then, something comes along that has a beginning to it and you can feel it kind of coming up the back of your neck. If you’re quick enough, you can keep it going just by paying attention to it. After you’ve got as much of that as it’s going to give you, you maybe refine it. I think stories are just putting a front end and a back end on what’s going on all the time in your head. So, there is a narrative structure to it for me. It’s not just a string of images or words.

How successful do you feel you've been at translating those thoughts and ideas into studio recordings?

A record is a picture of what you’re writing at the time. I don’t have a plan. I don’t decide what sort of record I’ll make in advance. I’ll find out how I feel about it when I’m done with it. It takes me a very long time—sometimes, several years—to begin to qualify it and say what kind of record it is. With some of them, I never really know. You have an impression of it that’s good or bad, melancholic or vivid and that’s about as specific as I can get. The short answer is I really don’t know. The short answer subtext is it’s always the same old shit because I’m the one doing it. Whatever it is, it’s mainly made up of my limitations which are just as important as my abilities. I hesitate to say that because you’d like people to go out and buy your record. If you go out there and say “Would you like to buy the same old shit?” you might be turning off a couple of potential buyers. [laughs]

Having said all of that, some records I really like when I'm done with them. They’re in the minority. I really hate more of them when I'm done. I can speak in plurals because I’ve made too many records. The majority I have mixed feelings about. A mistake I’ve made consistently is that I record too often. My first contract with Capitol required a record every six months. It’s pretty tough to make records with those kinds of deadlines since I write most of the stuff and don’t play with the same rhythm section all the time—and never play with one onstage. But I got into the habit of it. The industry likes it if you churn a lot of them out. I’m definitely trying to slow that down.

Photo: Private Music

Photo: Private Music

What first attracted you to the acoustic guitar?

It was and still is about the tone and the nature of the instrument in that a chord on a guitar is a real chord. It’s something people can get around. You can’t say that about a chord on a piano. I think you internalize the sound of a guitar as a listener and a player. With the piano, you don’t internalize it. It internalizes you. I will always be a tone player. I think most of us are, but some of us really zero in on tone as the heart of the matter.

For a long time, the guitar has been my primary interest. I see everything through the guitar. My day is almost always built around it. The guitar is almost always beside me, wherever I am. Playing the guitar is generally the first thing I do in the morning. Before I’m out of bed, I’ll reach out and grab it and play it for a few minutes. That happens on and off all day long, not for any great length of time, although sometimes I get an idea and want to work on something. Then I might spend a couple of hours on it in a stretch. It’s really the guitar and what I can write on it that I spend all my time doing.

Have you ever become bored with your instrument?

I did, but it wasn’t the instrument that made it happen. It was me. It was in the early '80s. It didn’t last long, maybe a year or so. It wasn’t that I lost interest in the guitar, but I couldn’t find my connection with it. I’d sit down to play and literally played the same stuff every time. I wasn’t getting any ideas and it scared me to death because I depend on the guitar. It really is my life. I couldn’t understand it. I thought it was me or the job, but I was dead wrong. I was taking everything too seriously. I was wearing myself out and not getting any sleep. I was screwed up most of the time and you just can’t be that way.

The reason you start getting more sleep and stop getting screwed up is so you don’t lose the playing. Dizzy Gillespie once wrote a great biography called To Be or Not to Bop and he made it really clear that sooner or later you have to focus on staying intact or you’re not gonna be able to play. When I met Dizzy in Italy once, we talked about how you’ll give up a lot of stuff—mainly bad habits you don’t mind losing—so you can keep playing. Well, you do mind, but maybe they’re worth losing.

You once said “I’ve developed some respect for my own blindness.” Tell me what you meant.

If you play guitar and you’re crazy about it, it’ll reflect everything. It takes you a while to put that together. The guitar reflected that I wasn’t together and after a while I realized that. It wasn’t that I had lost it for the guitar. The guitar is great that way. It’s like The Picture of Dorian Gray. It’s always just fine and always will be. The painting was always functioning, alive, working, and doing its job and the guitar is like that. The guitar shows you who you are and that picture got uglier and uglier.

One of the other ways you screw yourself up is by trying to see everything straight and clear, attempting to answer all the questions before you, and knowing everything about what you’re doing. You can’t. The way to get a little bit of self-knowledge is to accept that and know that some nights, every now and then, you’re gonna go out there and just stink. You’re gonna be horrible and that’s the night it’s time to be horrible. There’s nothing wrong with that. But if you hope that will never happen, you’re way out of line. If you can accept it, that’ll really help you get happy. It’ll especially help you write. You’ll find out everything is fine. Once I accepted that, there was more of me.

Do you believe artists must suffer to make great art?

I think if you really examine it, it doesn’t apply, period. All a starving artist does is starve. You can use misery and unpleasantness in whatever you do, music or otherwise, because it can sometimes inform why you’re doing something. It can keep things dimensional instead of flat. We all have the same problems. It’s what we really have in common. But there are lots of really miserable people that have really been hit hard by something. That doesn’t make them artists. It doesn’t work that way. There’s nothing about being happy or having peace of mind that will kill imagination. I think it really helps. You do have to leave room for despair now and then. I really do think it’s inevitable, necessary and human. It will always come to the party sooner or later. But all in all, I’m basically a happy guy.

Standing in My Shoes is the most funk-based album you’ve worked on. Describe the decision to go in that direction.

For me, it’s more of the same old shit. [laughs] It’s just me again. It was a record I intended to make about 26 years ago with David Z, who produced it. We were planning to do that and it would have been exactly the same record. On that album, I re-recorded "Standing in My Shoes" and "Vaseline Machine Gun"—which I wish I could re-title. We did those because those were tunes David wanted to produce 26 years ago. But his career took off with Prince and it just never happened. So, the record that would have happened 26 years ago is the identical record that got made—the same kind of material and the same kind of production.

I remember David and Prince would record in the studio at Sound 80 and then go check the bottom end at a gay bar downtown. It had the most reliable bottom end he could find. [laughs] So, he and Prince would walk in there and put up their mixes and come back and tweak whatever they had to tweak. It was hard to get the subs right at Sound 80.

I would see Prince occasionally when he was about 16 or 17 working at Sound 80. He hadn’t released a record yet. He was just the shyest human I think I’ve ever known. He wouldn’t talk to you. It wasn’t because he was a snob—he was just uncomfortable with people. It was always a closed studio, but if he was working in the studio and you walked by him, you’d see him frequently playing with his back to the glass so he didn’t have to see people.

I always heard a lot about Prince because he was the best friend of the younger brother of my best friend—a guy named Don Govan. They grew up together, so I knew a lot about him. He was in the studio a lot. He didn’t perform anywhere that I know of, but he must have been somewhere. He was a kid. Who was paying for that studio time? I still don’t know.

A lot of people have recorded at Sound 80 and never let you know it. Kiss made a record there. They thought Minneapolis was too square to put on the back of their record. Cat Stevens, who I did some touring with, made a record there. He carried his own cook with him. She was whipping up some of the best-smelling food back in this little coffee lounge in a wok or something. I stuck my head in there and said "Gee, what’s that?" And she looked around at me and gave me the biggest sneer and said "vegetables." So, I didn’t talk to her anymore.

Photo: Private Music

Photo: Private Music

After several ensemble albums, you returned to the solo guitar format for One Guitar, No Vocals. Tell me about that decision.

The main reason is the head of A&R at the label wanted it. They told me to do it. But I’ve asked every record label “Can I just do a solo guitar record?” because it’s really how I first showed up in the marketplace. What I’m always trying to do is write a guitar tune. It’s my big thrill. So, the chance to do the record was really welcome to me. Fortunately, I had a fair amount of material, so away we went.

The label did ask for a literal title, specifically. They didn’t give me the title itself, but after we all agreed I’d be happy doing a solo record, they asked me to indicate in the title somehow that it was a solo guitar record with no singing on it. I said it wouldn’t be a problem.

What input do record labels typically provide when you’re making an album?

What has tended to be the story almost every time is “Do what you want, but talk to us about who the producer is, where you’re gonna do it and how we can get ahold of you while you’re doing it.” The other things I’ve run into are “You’ve gotta have other instruments” and “We’d really like you to have a ‘chick’ singer.” I’ve managed to avoid that. The fact that people like Rickie Lee Jones and Emmylou Harris have sung on some of my stuff has nothing to do with them being “chicks.” Another theme of my career is the idea that I should make a Christmas album. I used to suspect it, but because I’ve kind of canvassed audiences, I know that one of the reasons they keep coming to hear me is because I haven’t made a Christmas album or done a record with a “chick singer.” I mentioned that in Boulder, Colorado once and Michael Murphey came backstage and said “You know, Leo, I made a Christmas record with a ‘chick’ singer.'” [laughs] He made millions off it. So, that’s it. They’ve never said “You’ve got to do this tune or make a record this way.” They’ve always left me pretty free to do stuff.

Compare the collaborative approach you’ve taken in recent years to working solo.

The kick you get when you hear something you like when you’re in the audience is what it’s like to bring other people in to play with you in the studio. I’ve had people in the studio because I like hanging out with them more than I’ve given any thought to how they play. Ideally, both happen and that’s great fun. After all the years of playing and performing by myself, it’s a huge thrill to hear this other stuff. I think it can also be a problem sometimes because you’ll fall in love with everything you hear because you’ve got no experience with it. You might not exercise a lot of judgment. It’s nice to have a good producer in that case.

When you play solo, you have to know how to relax and get in and out as quickly as you can and not try to get it exactly right. I’m getting better at that. It applies to anything, but it seems to be more true of solo stuff, because with solo stuff, you can’t fudge the pocket. It has to be there on its own. It’s a matter of relaxing into it, no matter what kind of tune it is, and as Chet Atkins once told me, “waiting for the beat.”

“Chamber of Commerce” from One Guitar, No Vocals was originally titled “Goddammit!” and served as a tribute to Michael Hedges. But onstage, you introduce it with a story about reacting to a fellow motel resident complaining about you making too much noise. Why did you revise the track’s name and the story behind it?

I decided that the people who know me would know that I wrote it with Michael in mind. It seemed a little presumptuous of me to title a tune as a memorial to a friend.

Was the original title designed to suggest the idea of “Goddammit, he’s gone?”

Yeah, and “Goddammit, God!” There’s this Jewish tradition, a prayer for the dead called the Kaddish. I used to think the prayer involved walking out on a storm-swept hill in the middle of the night and shaking your fist at God while saying “What the hell do you think you’re doing to us? Quit it!” According to one of my manager’s daughters, the Kaddish is just a prayer for the dead. You don’t go out and yell at God. But I’ve never reacted that way to the death of someone before. It was everything you would expect. He was a good friend of mine and I was just very, very angry about it. It really just pissed me off. So, sometimes you take out those moods on the guitar.

A long time ago, I had written and recorded a song on Burnt Lips called “Low Thud.” It was on a 12-string and the low E was tuned to a low A. Hedges and I were doing a tour somewhere and he said “Remember ‘Low Thud’ and you had that E tuned down?” I said “Yeah.” And he said “I do that now” and he did. He had some tunes that way. So, I went in that direction because it was a familiar place to both of us and just started fooling around.

I was in a motel room in Pawling, New York in 1997. I got the call about Michael a couple of days before that. I had been trying to play through that kind of feeling I had and I remembered he liked that bit on “Low Thud.” Then I got a call telling me to be quiet. It’s the wrong thing to say to a guy who’s already pissed off. So, it’s a part of the experience of that thing and it gave me another way to introduce the tune without having to go through Michael’s intimate story.

Michael Hedges and Leo Kottke perform on VH1, 1988 | Photo: VH1

Michael Hedges and Leo Kottke perform on VH1, 1988 | Photo: VH1

Did you and Hedges discuss recording together?

We’d always talked about recording. We had about six pieces worked up together. There was some really neat stuff—and some terrible stuff. [laughs] We really butchered a couple of things. I remember we tried doing "The Night Shift" by the Commodores with both of us singing. Oh, it was hilarious. But I loved the tune. I was the one who suggested it, actually. It almost made it, but it didn’t quite work.

There are a couple of bootleg cassettes out there of us playing together, but who knows if they’re any good. When we played live, I would play my guitar and he’d play a high string. It provided a nice separation to the thumb problems you get into when you have two real thumb-y players like us. We kept talking about my coming out here Michael’s studio in Mendocino to record. The idea was I could stay at his place, but as usual, I procrastinated. Michael never did procrastinate. If he got a bee in his bonnet, he’d act immediately. But I don’t. I’m slow.

“Bigger Situation” is a key highlight of One Guitar, No Vocals. Describe the creative process behind this complex piece.

It started out as three separate pieces and somewhere along the line they connected beautifully. The middle section folds back in on itself, so they became one piece. It happened over several years. I was knocked out about that. It’s all the same geography. It’s sort of like finding out you’ve been living next door to your brother for 20 years and didn’t even know you had a brother.

What amazed me about "Bigger Situation" is that it goes over great live because you’ve got to kind of pay attention to it. You can lose an audience sometimes. I never really know what I’m gonna do. I’m playing a few things off the new record, but I’ll have nights where I don’t play anything from it. That used to be a theme with me during the old Private Music days. People from the label would come to my show in Los Angeles. I’d have a new record out and wouldn’t play anything from it. [laughs] Sometimes, I’d do the publicity they set up for me on radio or TV and I’d play something that’s 20 years old. They would always prefer I play something off the new record. I do see their point.

Several of your recent records feature remakes of older tunes. What makes you want to revisit older compositions?

Part of the reason for it is just to fill out the record. You just don’t have enough stuff, so you re-record something. So far though, I’ve only re-recorded stuff that kinda needed it. Either it hadn’t been recorded the way I do it now or the performance or sound of when it was first recorded sucked. “Morning Is the Long Way Home” first appeared as a vocal on Ice Water and second on the first Capitol greatest hits record Did You Hear Me? where the break was excised and put up independently. As far as I can recall, that was the last time it was done and hasn’t ever been recorded solo. I get a lot of requests for it because I stopped playing it for a lot of years. I started playing it again in the last two years. I like it. It’s a kind of tune I don’t often write anymore, so it’s nice to get it on One Guitar, No Vocals.

The Shamen sampled “Morning Is the Long Way Home” for their track "Comin' On" from the 1992 album Boss Drum. What did you make of it?

They used two different things from the tune and very little of it. They take approximately from the middle of one bar to the middle of the next. They didn't lift out an intact block. Just by selection, they kind of built their own Leo. It's nice. I like it. You can be sampled all wrong and you can be ripped off or someone can actually make something with what you did where you become part of their process. They didn't just glue something together. They did it right.

Photo: Private Music

Photo: Private Music

You toured with the late Joe Pass in 1994. Reflect on working with him.

You know, there are a lot of guitar players who’ve died in the last handful of years. A lot of them happened in plane crashes and other violent, accidental sudden deaths. But Joe died in his sleep with a smile on his face. In my experience, great musicians are usually people you’d love to be around even if you hadn’t heard them play or didn’t know they played. Joe was one of the most straight-ahead, in-your-face people I’ve ever met and it was such a privilege to play with him.

He was just being the height of generosity to play with me in that situation during the Guitar Summit tour, along with Pepe Romero and Paco Pena. He was perfectly happy to step into a 12-bar blues and play with me. It was really a great gift. A lot of players of his ability wouldn’t have done that. He was happy to do it. Some nights it was a collision, but some nights it actually worked and was so nice.

I was hung up on his tone on that tour. When I saw him a few times in Australia, he would get this great tone and it kind of changed my mind about those big humbuckers and plywood tops. Joe was convinced carved archtop guitars weren’t worth it. He said they’re just a problem on a pick-up because you’re going to use the pick-up anyhow, so just get a pressed plywood top and put a pick-up in it. He’s got a lot of support for that argument. I loaned him my Demeter DI and toward the end of the tour, he thanked me for giving it to him. I couldn’t bring myself to say "I didn’t give it to you Joe. I gotta have it back." [laughs] I don’t know where it is now, but I’m glad he got it.

Joe would come off stage several nights on that tour and say "What a great night for the guitar." When I met him the first night in Australia, we were playing on a TV show together with John Williams and Paco Pena, and we took a cab somewhere to another part of town and he said "I’m intellectually tired." He didn’t really want to play anymore. And then he would go out and play his ass off on that tour. He mentioned a couple of times how much fun it was to be playing again and how nice it was to play solo. It was quite a wonderful thing for all of us and I know I’m not putting words in anyone’s mouth.

There was a plan to release a live album from that tour. Why didn’t it emerge?

There was so much contractual shit that it was pretty much impossible. Also, none of us wanted to do it. When the idea first came up, Joe was the first one to say "If you’re going to do it, don’t tell me. I don’t want to know the red light is on. If the red light’s on and I know it, I choke." It’s really interesting because he’s an improviser. Pepe said "Yeah. I felt exactly the same way." We just wanted to play. The show did get recorded a couple of times, including San Francisco at the War Memorial Opera House. I don’t know where that tape is. It sounded pretty good, but it’ll probably never be heard.

What goes through your mind when you reflect on your own mortality?

I don’t think of it in terms of being dead, but I think about it in terms of “You have a curve as an organism—if not a soul—and what do you do with it?” I think early on, you just figure out that it’ll come to you. But at a certain point, I started feeling you have to choose it. It doesn’t come to you.

So, you have to choose what happens to your soul?

Yeah. If you do nothing at all, that’s a choice. That tends to be my favorite choice and I now know it’s one of the worst choices you can make. The choice not to choose—that’s a bad choice.

What choice do you make now?

That it’s better to act it than to think it. I’m trying to do that more. That means you should make your mistakes out front, rather than premeditate them. You’re gonna tend to get to the same place given a certain degree of participation in your own life. You might as well get there by choosing, period. Doesn’t really matter what you choose. But by choosing, rather than by not choosing, you’ll find that it’s better to act than to be acted upon or that it’s better to act than it is to react. I didn’t know that earlier. It takes a little bit of the other kind of mortality thoughts like “I’ll be dead in awhile” before you get that—before I did.

Is your outlook based on any spiritual beliefs?

The guitar has probably been my spiritual connection. I know when I started playing, it definitely was. It got me out of bed. I was in bed for two months once and it cured me. I’ve been playing since I was five, but it was the guitar when I was 12 that took me apart and gave me a life. I knew instantly that I’d be playing for the rest of my life and that it was all I wanted to do. I didn’t have to think about a job. I could just go with it. It was a spiritual experience and remains one.

I’m going to toss out some names, phrases and ideas. Tell me whatever comes to mind.

Oh boy. I’ll get in trouble. [laughs]

Leo Kottke, 1970 | Photo: Symposium Music

Leo Kottke, 1970 | Photo: Symposium Music

12 String Blues, your first album from 1969.

There was a kissing law that went into effect during the time I was playing at the Scholar Coffeehouse during the time that album was recorded there. You could not kiss in public in Minneapolis. Mike Justin, the owner of the place, was having to go around telling people in this little bitty coffeehouse that they couldn’t kiss each other because the police were coming in and busting him and fining him on this.

That was in Minneapolis in the ‘60s. It was horrible. I’m embarrassed to talk about it. I don’t know what happened to that ordinance. But I think it was observed in the breach, rather than the application.

If there’s still a master tape somewhere, I wouldn’t object to the album being on CD, because it was the very first thing and what’s wrong with it is what’s genuinely wrong with it. Whereas with Circle ‘Round The Sun, the next record, the mistakes were made in pursuit of something. Circle was supposed to be the professional version of 12 String Blues. That’s why Circle sucks and why 12 String Blues is whatever it is. The vocals on Circle were terrible. And on 12 String Blues, you can hear a door opening on it. It was recorded with two old EV dynamic mics on goosenecks and a Viking quarter-inch tape recorder. Man, I’ll never forget it.

“Geese farts on a muggy day.”

My daughter’s first word was “daddy,” which pissed off mommy, but the first sentence that any of us ever heard was “Daddy don't sing!” [laughs] Little kids frequently have trouble with a deep voice. Babies can be scared to death by them. Took me a while to figure that out.

Baggage check.

One of the great things about having a signature model guitar is that when the airline breaks one, there’s another model I can get right away that’s gonna sound very similar to the one they squashed. They get one every year-and-a-half I’d say. I’m used to it now. It used to completely freak me out, but as Dick Rosmini said, "If you really know how to play it, it doesn’t matter what guitar you’re playing." And what that means to me is you can always make it work. You might be miserable doing it, but you can always make it work.

Prisons.

I have a lot of volunteer leanings, but they all revolve around playing. I don’t play benefits, but I’ll play hospitals, schools and prisons. I’m cutting back on prisons. [laughs] I haven’t played many of them. There’s a certain kind of prison I don’t want to play anymore and that’s a state prison.

They are not a good crowd in a state prison. It’s a tough audience. It’s a room full of depressed people. In a federal prison, if you do your job right, you can work it like a crowd. It’s more congenial there. Things are just easier when you walk into the federal prison. You feel better and so does the prisoner.

I can’t exaggerate the difference between a federal prison population and a state prison population. It’s a different experience. The federal prison has people involved in things like white collar crime, interstate stuff and smuggling. All you have to do is think about what state laws cover compared to what federal laws cover and you’ll see why there would be a different mood in a state prison.

Ralph Towner.

Oh man. One of the few 12-string players and a great one. I love Ralph. He does something that I think is really brave and worth emulating. He doesn’t use a pick-up, even on a 12-string, which is a bastard to mic. He just puts two mics up there and that’s it. It’s hard to get a mic sound off a flat-top. It’s no problem with a classical guitar, but it’s tough with a flat-top.

Gun control.

There’s a great song by Cheryl Wheeler called "Take Away the Guns." Amen to that.

Bill Clinton.

You know, I was in the Oval Office when he gave his radio address on Lincoln’s birthday two years ago. Shawn Colvin knew George Stephanopoulos. I was snowed in and she was playing the Birchmere and I went to go see her. George was there and he came backstage and his appointment secretary invited me to drop in the next day at the White House, so I went.

There are a couple of things I remember. One was the White House photographer was there and he spent a long time lining up the bust of Lincoln. He wanted to shoot it from below the desk and get just the right look and angle. The first thing Clinton did when he walked in was reach over to the bust, tweak it and move it because he didn’t think it looked right. So, he’s a real detail sort of guy. The other thing was, I never got my picture. You line up and you get your picture taken with the president. I told him "Thanks for talking to Salman Rushdie.” I voted for him. I’m pretty far to the left of Democrat, but Democrat will do. Sometimes I don’t know where the hell I am or fit. But it’s got to be off to the left somewhere.

Chicken feet.

Usually, when people throw them on stage, they’re stuffed chicken feet made out of corduroy. Sometimes, they come with a note attached.

I once tried to kill a chicken when I was a kid and it didn’t go well. That'll put a dent in your self-esteem when you go to strangle a chicken and find out you can't do it. It wasn't for lack of trying. You twirl the chicken over your head, give it a kind of grace note and then its neck snaps. This was on a farm where they do that every day and I couldn't do it. We eventually backed a tractor over its head. And even then it didn't die. It kept kicking. So, we left it there for about a half hour and it finally expired. It wasn't a great day for the chicken. As they say, it was a tough bird.

Leokottke.com.

It’s embarrassing and really weird to have your own website. It’s like putting your name up on a corkboard at Wal-Mart. But the people who did it, did it beautifully. It’s fast and database-driven or something. You can go anywhere very quickly.

By the way, typing lessons? I know now why I play like I do because when I was teaching myself to play the guitar, I was also learning to type. That was in Muskogee and the typing teacher’s name was Enis. He’d get up and type. He was a typing machine. It was astounding. You learn finger independence when you type. You get that thing going. I know it helped. I’m about 60 words a minute on a good day.

The thing that intrigues me most about the website is there’s this little section where I get to mouth off. I don’t care what the issue is. I’m going to have to be careful though because Good Lord, can I open my mouth. And I hate beating people over the head with anything. We can all make up our own minds. What we don’t have is enough music. More music please.