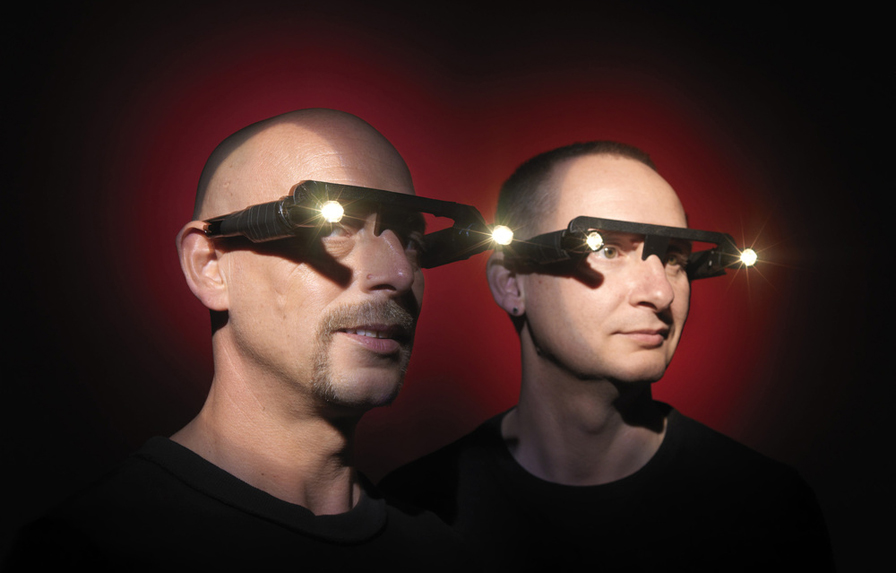

Orbital

Beats of Daring

by Anil Prasad

Copyright © 2004 Anil Prasad.

Orbital is responsible for some of the most exciting and intriguing music to emerge from the electronica movement. Comprised of brothers Paul and Phil Hartnoll, the British duo’s singular brand of melodic and evocative compositions have enabled it to survive and thrive in the flavor-of-the-second techno environment that saw multitudes of acts appear and disappear in the blink of an eye.

Orbital first hit the scene with the addictive 1990 single “Chime.” The track became an unlikely U.K. hit and served as a formative moment in the history of what became known as the “Intelligent Dance Movement.” Orbital’s music is unique in that it feels equally at home on the dancefloor and in the easy chair. Unlike many of their contemporaries, the Hartnolls are unafraid to use their music as genuine storytelling vehicles. Whether reflected through mood, sound effects, vocal samples, or lyrics, Orbital explores beauty, benevolence, excess, and ethics across its output. The approach is best epitomized on career high water marks such as 1994’s Snivilisation and 1999’s Middle of Nowhere.

The duo’s impact also extends into the realm of performance. While the majority of techno acts cling to pre-programmed agendas in concert, Orbital incorporates improvisation into its gigs. The Hartnolls use their banks of computers and keyboards to add, subtract and extend passages in direct response to the audience’s reaction. They also incorporate spectacular, stadium-rock visual effects into their shows. It's a potent combination that has propelled the act to lofty heights, including regular headline slots at famed music festivals such as Glastonbury, Roskilde and Lollapalooza.

Orbital’s influence is felt in other realms as well. Acts as diverse as Kraftwerk, Madonna, Queen Latifah, and Yellow Magic Orchestra have commissioned remixes from them. Film directors have also approached the pair to contribute music to scores for Event Horizon, The Saint, Spawn, and Octane. The act has been responsible for their own high-profile visual works too, with groundbreaking videos such as 1996’s “The Box” having been screened at film festivals worldwide.

The Blue Album, the duo’s ninth record, served as a series of audio snapshots chronicling the many styles and themes they've embraced during their career to date. Minimalist musings, cinematic soundscapes, full-on techno stomp, and percolating pop all have a home on the disc. Its moods are equally diverse as it shifts between the dark and desolate to the heights of joy and celebration.

Phil Hartnoll began this conversation by discussing the compositional instincts that inform the duo’s work.

Describe Orbital’s creative process for me.

There are all sorts of ways a track can start. It’s almost option paralysis sometimes. The process can be fast and simple or long and drawn out. There are so many different choices and exciting ways of doing it. For instance, for the track "Style" on Middle of Nowhere, Paul came down to the studio one Friday and wanted to carry on with a different mood than what we explored the day before, so he quickly whipped something up by sampling a Stylophone which is a pocket, electronic buzzing fad machine that was quite big in the ‘70s. So, he restricted himself to the Stylophone, fiddled about with it and that was "Style." But on other tracks, you can spend bloody months on it if it’s not doing it for you. It’s got to touch you somewhere within. I think that’s the key point really.

Is “composition” an appropriate word for Orbital’s approach?

Not really, but it is the best one available. I wouldn’t call myself a musician really. I couldn’t get onto a piano and play you a tune at any high standard that you’d think somebody with a career in music might be able to. I had 10 lessons with the vicar’s son when I was 11 and that’s it. [laughs] Paul was sort of self-taught at guitar. I can read music and have a basic understanding of musical notation and technology. So, it’s definitely more of a layering and construction kind of composition. We have these huge sampled riffs and we play other things one hand at a time and build them up. It’s not intellectual in terms of musical theory. We have a basic knowledge of keys, but we don’t follow it. It’s all done by ear. It’s what sounds right and it doesn’t matter if it’s musically correct or not.

I’d say that even though I’m not a musician, I do play the stuff. A fundamental way of talking about it is to say the computer replaces the 24-track tape machine. If I’m playing the guitar, I’ll play it until I get it right on one track. I’ll play the part over and over again until I do. On a computer, you play a part on a keyboard and you can use the computer to record your movements, including velocity. So, I can’t see the difference between putting something down on a traditional tape machine as opposed to the computer. There’s no distinction between the two.

Bill Laswell said "Notation exists to respect or fulfill memory, but tape can fulfill memory too." It sounds like you’re extending that to say a sequencer can do the same.

That’s exactly it. The problem is people look at things in traditional terms. But people shouldn’t be comparing things in this way. Working with a synth is a different way of producing a sound. I think synthesizers made a bad name for themselves when people started using them to try and imitate real instruments. That shouldn’t have happened because people went "Oh God. That doesn’t sound like a piano. That doesn’t sound like this or that." But people can accept a sound source on its own. The frequencies you can get out of a synth are things you could never get out of an acoustic instrument. So, it should be championed for what it can do in those terms. This also gets into what the emotional connection to music is and asking "What is sound?" or "What is music?" It’s a real can of worms.

When people look at electronic music and say it’s not emotional or very sterile, I can agree in some cases. Some techno music is very sterile and you can almost see the stainless steel glimmer on the sounds, but that’s what’s good about it too. [laughs] The penny just hasn’t dropped with a lot of skeptics. There’s nothing to be skeptical about. Some people think "Oh, let’s suppress the new music. The old music is the greatest." They feel threatened or challenged by it. There’s a lot of misunderstanding going on. I’ve listened to pots and pans being crashed and smashed and if it produces a response from me, who’s to say that's not music? Where's the defining line? Who gets to say what is worthy and what isn’t? So, either you take the whole thing seriously or you don’t. Music shouldn’t be taken so seriously. There should just be a natural acceptance of music, period.

Orbital defied expectations by incorporating more and more live instrumentation into its albums as it went along. Tell me about that shift.

It’s just what turned up very casually. There was no conscious decision. We have a friend who’s a drummer and we would just go over to a big recording studio across the road to record him doing loads of drumming to things we’ve done—bits and bobs and playing to a metronome. We’d use his stuff as breakbeats or chop them up and use just one note. You’ve got a whole source of drums when you do that. Another example is when we were writing the first track on Middle of Nowhere called "Way Out." We felt it needed a trumpet in there, but I don’t want to get a trumpet sound on my synthesizer. It would sound awful in my opinion. We wanted to hear a real trumpet. So, we knew a friend of a friend who’s a trumpet player and asked him if he wanted to pop in. That’s when we got our notators out and used them to see what we’ve written as a musical score so he could read it for his trumpet playing. We also wrote his part with a sound that was similar to a trumpet and he popped in and re-did it for us. It was great fun.

Describe the working relationship you share with your brother.

We just sit in a little room and just lock into the work. Sometimes we don’t say anything to each other for a good hour or so and just tweak around and fiddle about. It depends at what stage you’re at in the work. It’s a very different process from beginning to end. Sometimes we just sit there talking about what we’re doing and how to form things. That’s obviously got some benefit because we know each other and have very similar musical tastes. We give each other a lot of space musically. If Paul’s working on something and I don’t like it, I say it. But if he genuinely likes something he’s done, who am I to say something’s wrong? So, we talk about things in little bits and pieces, rather than whole songs or tracks.

Snivilisation is the darkest, least dance-oriented and most political album Orbital made. How do you look back at it?

It came from us being fed up with the way the world is and having the weight of it on your shoulders. It was a time when we wanted to incorporate the irony of it all. It kept popping up as a theme running through it. It’s a mood, not a concept. It was a reflective record. That’s why we ended up calling it Snivilisation and putting a sort of grey cover on it. Snivilisation came out around the time of political bickering with the Poll Tax. It was an awful tax imposed on British people that caused a riot. It also caused a revolt in the early U.K. when they tried to introduce it in 1381. Basically, the Poll Tax was a political carve-up. It was also around the time of the U.K. Criminal Justice Bill. Those were grey times.

The "Criminal Justice Bill" Snivilisation b-side was a particularly strong statement in that it was four minutes of pure silence.

Yeah, the Criminal Justice Bill was ridiculous! It’s very Orwellian. Bloody burn your books? Fascist! They tried to put a bill in law to actually point the finger at repetitive beat music as a dangerous influence! Repetitive beats? [laughs] That holds to rock too, doesn’t it? Most songs have a repetitive beat, don’t they? The fact they did it was outrageous really. There’s justice for you. I was outraged by it. It was a civil liberty thing. Rather than look at the broader spectrum, they were picking on the music, trying to outlaw it. It’s the sort of thing they did in America down in the South. Rock and roll was devil music at one time. It’s the same sort of thinking.

Orbital always struck me as being more related to Kraftwerk, Tangerine Dream and Jean-Michel Jarre than it did to the house and techno movements. Do you agree?

Yeah, that’s exactly it. We got sort of lumped into the acid house movement. We’re obviously influenced by it and like it, but I couldn’t understand it when people said "Listen to this new music! It’s called ‘house’ from America!" It’s all the same sequenced stuff I’ve heard in tons of other stuff before. It reminded me of ‘70s disco because of the constant snare, bass drum and hi-hat thing going on. There was high energy music before that. So, I have enthusiasm for the movement, and I’m glad it made a stir, but the idea that it was new is confusing. Kraftwerk was very much a big influence. My elder brother had Kraftwerk’s Autobahn and that was the first record I had heard that had all these strange noises and sounds. It was like, "Wow!"—the whole idea of it being a conceptual piece broken up into five perfect songs that were essentially instrumental. I’d say that was a major influence. It all started from there.

There’s Rick Wakeman too. That was one of the first concerts I went to see. I got my brother to take me to his show because I was too young. Blimey, it was the tour for Journey to the Center of the Earth. That was sort of soundtrack music and that’s a heavy influence more than dance music is really. But you have all aspects. The Dead Kennedys and the punk idea is there too. We have a wide range of musical influences and you’ve got these things called samplers and electronics that let you bundle it all in. That’s how we express ourselves. It’s about whatever’s going on.

Describe the creative process behind The Blue Album.

Unlike most of the LPs we’ve done, apart from the first one, we went into it with lots of bits and pieces to start tracks with. It ended up being a more celebratory record. I haven’t had so much fun making music with Paul in years. It’s not that it was all grim before, but this one was much more upbeat. We both felt a greater sense of freedom when making the record. In many ways, it reminds me of the earlier days in spirit. It has some film soundtrack-sounding stuff like “Lost” and “Transient” that could have been on In Sides. “One Perfect Sunrise” could have come off The Brown Album and “Acid Pants” could be from Snivilisation. I don’t know if there’s been any musical progression, but I’ve never taken much notice of that, even for bands I follow. It’s just music to us, but it does feel like things have gone full circle with this album.

Does the track “You Lot” on The Blue Album sum up Orbital’s worldview?

Yeah. I was really pleased to be able to include the speech we’ve got in that track. It sums up a lot of things for me about the state of the world. It came from a British TV drama called The Second Coming. Typically, Christians believe in Jesus coming back down to earth and taking all the believers up to heaven while the rest of us burn in hell. But in this drama, Jesus came down and he ended up being a very working class guy from Manchester. He was a normal beer-drinking geezer who realized he was Jesus. During his speech to the masses, he said God doesn’t really exist anymore and chose to leave matters in the hands of the people. He also said you have to look inside yourself for direction and banished all religion. To me, that’s a good thing. I don’t believe in banishing religion or spirituality, but I do believe people should look inwardly for their God rather than outwardly.

We are very, very immature as people who consider themselves civilized. Since we made Snivilisation, that’s been on my mind. Nothing’s really changed for humanity in thousands and thousands of years in terms of how people get on with each other. We don’t really know what we’re doing or understand the consequences. Mad Cow Disease is a fine one in terms of looking at what happens when you mess with the food chain. The Iraq War is another example. Saying “Look how civilized we are” is just a load of rubbish. But my tendency is to put an opinion across, rather than preach. People have to make up their own minds. There’s some silly, comedy tracks on the album as well. We’ve also got “One Perfect Sunrise” which is an emotive track that has a looking out from a hilltop vibe. It’s not all doom and gloom.

How would you describe the influence Orbital has had on the electronic music scene?

That’s difficult to say. You hear tracks by other acts and think “That’s a bit like us” and then we’d make tracks and think “Well, that’s a bit like them.” But we really never fit in with the rest, musically speaking. We draw lots of influences from lots of different styles and not just from electronic music. I can certainly put my hand up and say we’ve encouraged a lot of electronic bands to play live and meet their audience, rather than just being bedroom producers. I think influencing a single person at a time can also be the most fantastic thing. When somebody comes up to you and says they’ve made a connection with your music and proceeds to tell you a story about their first acid trip, it’s great. [laughs] I’ve been there, done that and worn the t-shirt with other bands. It’s amazing to think that people have had similar experiences with your music. You know, it was never about fame or fortune for us. It’s about making those connections. That’s the root of what Orbital is about.