Donate to Innerviews

Since 1994, Innerviews has provided uncompromising, in-depth interviews with musicians across every genre imaginable. And it does that with no trackers, cookies, clickbait, or advertising.

Your donations are welcome to help continue its mission of highlighting incredible music and artists, without any commercial considerations.

Your contributions will be instantly transformed into stories and videos, and cover hosting and web management costs. Importantly, your dollars will help ensure Innerviews remains absolutely free to all visitors, independent of their ability to financially support it.

Please consider making a donation today by using the PayPal QR code below.

Paris

Enemy Alliance

by Anil Prasad

Copyright © 2006 Anil Prasad.

Hip-hop artist and producer Paris has never shied away from infusing his music with incendiary, thought-provoking messages. His most recent solo album, 2003’s Sonic Jihad, offered a fiery indictment of the Bush Administration’s track record of deceit, destruction and incompetence, as well as a brutally honest look at issues plaguing America, including inner city decay and black-on-black violence. The San Francisco Bay Area-based rapper also struck a sensitive nerve with “Bush Killa,” a controversial single from his 1992 album Sleeping With The Enemy that took on Dubya’s equally imbecilic father in a similarly hard-hitting manner.

While most focus on Paris’ in-your-face lyrics, the fact is he’s also an impressive producer and arranger that knows how to expertly situate his messages within unique and addictive hooks, melodies and beats. So, when he approached Chuck D to produce a new Public Enemy album for his Guerilla Funk label, the hip-hop legend quickly gave him the green light—but with one catch: he would have to write, arrange and produce the entirety of the disc. But why would a legendary lyricist, rapper and producer like Chuck D hand over the reigns to someone else? Chuck D responds to that question with one of his own.

“Why do music without taking on challenges?” he asks. “Paris was the only guy who could have pulled this project off. He’s one of those guys that can actually make music and also write lyrics. Today, they talk about Kanye West, but Paris was the prototype and has been doing that for years. In fact, Paris was Kanye West before Kanye West existed. Paris was able to bring a very unique musical application to Public Enemy from the Bay Area which has a sensibility of total music and funk. Paris epitomizes that whole existence. He’s very thorough, a very hard worker, and very, very serious about music and his state of being as a black man in society. So, if you’re gonna have someone deliver the music and lyrics, he’s the man.”

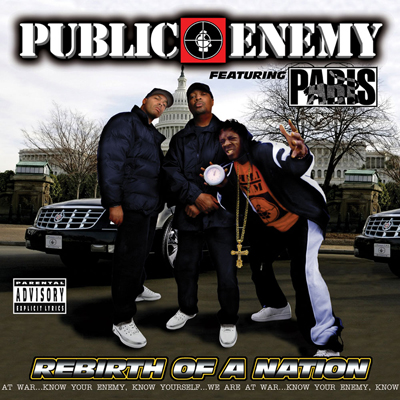

The result of Paris and Chuck D’s collaboration is Rebirth of a Nation, Public Enemy's 11th studio effort. The album title skewers the infamous 1915 racist film Birth of a Nation that denigrates African-Americans while exalting the Ku Klux Klan. It also refers to Public Enemy’s classic 1988 album It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back that put the act on the map with its revolutionary rhymes and innovative soundscapes built by layering myriad samples to create a furious aural assault.

In addition to Public Enemy mainstays Chuck D, Flavor Flav and Professor Griff, the album also features guest verses from socially conscious underground MCs including Dear Prez, Kam, MC Ren, The Conscious Daughters and Immortal Technique. Lyrically, the album explores the shared societal commentary found in Paris’ and Public Enemy’s best work, with production that offers a nod to the group’s past glories, with an eye to current sounds and flows.

Tell me how the Public Enemy collaboration came about.

I’ve known Public Enemy since around 1990. Our first official collaboration was me being in a video of theirs from Fear of a Black Planet called “Anti-Nigger Machine.” At the time, they were on Def Jam and I was on Tommy Boy. Throughout the years, we toured together as well. We had fallen out of touch for awhile and got back in contact around 2002. Chuck hit me up online and we got reacquainted. I ended up doing a guest verse on their album Revolverlution and they in turn did a guest vocal on my last album Sonic Jihad. Then I caught up with Chuck in person at KPFA radio in Berkeley when he was out here promoting Revolverlution. I told him I was interested in producing a full-length Public Enemy album for release on Guerilla Funk. He said “My time is short, so the only way this is gonna happen is if you do the work.” So, I ran with that and wrote all the parts, completed all the songs and forwarded him the competed tracks to learn. Then I flew out to Long Island and met with him and Professor Griff and did the overdubs. Finally, I returned back to the San Francisco Bay Area to finish the record.

Did Chuck have any input into the lyrics?

He didn’t have any input at all into most of it. The stuff was written for him and he might have had an objection or two, but the overwhelming majority is as is. The exception is the song “Invisible Man” with material that was pulled from “I” originally released on the Public Enemy record There’s a Poison Going On.

What were the key creative challenges you faced when putting Rebirth together?

It was a difficult task because there’s a particular kind of noisy sound that people identify with Public Enemy that is unlike anything else out there right now. The difference between our production approaches is that almost the entirety of my material is first generation. It’s not sample-intensive at all. I generally avoid loops and samples because I feel when you use that approach, you limit yourself to what the sample wants to do. Nine times out of 10, the end result isn’t as polished as it is if the sound is first-generation. Another thing about writing for Public Enemy is the fact that the tempos people associate with their better-known works are a lot faster than the tempos out there now. So, there was definitely an effort to bridge the gap between the two and focus on flows and inflections that I’ve identified as being associated with Chuck D on their better-known stuff. I used certain previous Public Enemy songs as templates for some of the tracks on Rebirth of a Nation. Let me break it down for you:

Hard Rhymin’”—This took a bunch of cues from “Prophets of Rage.”

“Rise"—I used a lot of cues from “Don’t Believe the Hype” on this one.

“Can’t Hold Us Back”—I deliberately intended this to have a blaxploitation feel. It’s loosely based on Curtis Mayfield influences.

“Hard Truth Soldiers”—This song has a West Coast gangsta feel to it. It has a sound that has been associated with me more than Public Enemy.

“Hannibal Lecture”—The same goes for this one, especially with the female chorus at the end. It’s more of a Paris signature production.

“Pump the Music, Pump the Sound”—This was supposed to mirror a song called “Show ‘Em Whatcha Got” from It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back. More than any other track on the record, it has an indisputable Public Enemy feel as far as sounding like records past.

“Rebirth of a Nation”—To me, this is more East Coast-based, especially as far as the drum pattern, chord progression and guitars go. It’s something intended to get the party going. It’s also something that would drop da bomb on you live in concert.

“Make it Hardcore”—This features classic East Coast production. To me, it’s necessary to represent both coastal influences.

“They Call Me Flavor”—This Flavor Flav solo song is just silly as all shit and is intended to lighten the mood halfway through the disc.

“Plastic Nation”—This was inspired by the template of “Anti-Nigger Machine” which they released back in the day. The subject matter is topical in 2006 because of today’s obsession with body image and plastic surgery.

“Invisible Man”—This was originally written by Chuck D for There’s a Poison Going On. I took the instrumental and reworked certain parts and added echoes, giving it a much more melancholy vibe to reflect the subject matter.

“Hell No (We Ain’t Alright)”—This is a remix of an Internet-only Public Enemy release they put out in response to Hurricane Katrina. This remix has a “Murder Was the Case”-ish West Coast ominous vibe to it.

Public Enemy is one of the most important acts in the history of popular music. How daunting was it for you to be personally responsible for adding another record to that legacy?

At first it was daunting, but this record represents another way for them to experiment, which is something they’ve done for a long time. On the other hand, they have put out a lot of stuff that to me has been suspect, like fan remixes and shit like that. Things like that made the weight of the legacy not as heavy as I thought it might be at first. I knew if I put the record together and did the best I could do given my abilities that I could do them justice. I’m at the point in my career in terms of production where I didn’t have any fears about it not being a good project. I was more concerned about being sure the record adequately represented both of us and that certain topical issues were covered. In terms of writing for Chuck, it wasn’t that difficult because I know Public Enemy’s catalog and his phrasing so well. I adopted that phrasing for the material I worked on. He has certain cadences that worked perfectly for what I do. Overall, it was an interesting project to work on. I had to take so many different things into account, including how people have perceived Public Enemy in the past, and the framework they’re known for. I had to adhere to it, combine it with my own approach, but still make sure I didn’t go too far out of people’s comfort zone.

Members of Public Enemy’s official Enemyboard forum have been split on the merits of the record. What do you make of the mixed reactions?

Most of the people on the Enemyboard are part of the group in some regard or are longtime followers, so that affects what they think. Also, there may be a coastal bias at work in that I’m from the West and have a West Coast production approach. The East Coast approach is still pretty sample intensive. There are also a lot of people who hate for the sake of hatin’. We came out very early and said this is something I wrote. There wasn’t an attempt to hide the fact that the record used a ghostwriting approach. I said from the start “This is my interpretation of a Public Enemy record in 2006 as a producer.” People write and produce for other people all day, every day. Most hits you hear on the radio were produced by someone other than the artist, so it shouldn’t come as a surprise that a group as experimental as Public Enemy would reach out to someone else that shares their vision, but might bring something different to the table. As for the disgruntled few, there were some people in the Public Enemy camp that were unhappy because they weren’t a part of the record and shit, I don’t know what to tell them other than what I’ve already said.

Terminator X is name checked on “Hard Rhymin’” but I understand he’s not on the record. Why include the reference?

Terminator X raises ostriches in North Carolina for a living, so he wasn’t available. The reason is the record is supposed to represent a throwback approach to making and remaking what I love about Public Enemy records. It was necessary for inclusion’s sake to reference the original architects of the group’s sound. So, it was a shout out more than anything else. In fact, the entire Public Enemy collective is referenced on the record. It really wasn’t intended to fool anybody. It was just a way of showing solidarity.

Who plays electric guitar on Rebirth?

“Hard Rhymin’” uses an altered sound source sample in Logic Audio. It has a half-chord key change progression during the entire phrase. For “Rebirth of a Nation,” my man Bruce Leighton at Datastream Studios played the part. He probably used a Stratocaster. Any time we use a guitar signal, it goes straight into the board. The outboard gear included plug-ins and we just messed around with the internal Logic amplifier simulator to get the tone. So, all the tones go in dry if they’re external. All of the keyboard sounds are Logic plug-ins.

Describe the importance of electric guitar in your work.

When it’s used, electric guitar gives hip-hop an edge that separates it from contemporary R&B. What we do is not rock music, but electric guitar bridges the gap and provides a sense of urgency that’s sorely needed because most current popular music isn’t particularly passionate or inspiring. I like music that’s ultra-aggressive. I don’t think hip-hop is even worth doing if it’s not. So, electric guitar is a useful component in what I do.

Live instrumentation was a key component of a lot of early hip-hop. Why do you think that’s no longer the case?

Unfortunately, most hip-hop is now keyboard-driven because the majority of hip-hop workstations have loops and patches that enable somebody with marginal skills to put tracks together. Artists gravitated towards the path of least resistance by relying on those pre-sets and what was easiest to do. As a result, electric guitar and real musicians became devalued and now a lot of hip-hop sounds the same. That’s what I believe. As time went on and music became more and more easy to make, it became devalued more and more. So, now you have people file-sharing and not giving a shit whether or not the artist gets paid. All of these things came into play and most music made today doesn’t have a shelf life. It’s like a snapshot in time. A lot of material released now is not really valuable as a catalog item because it isn’t something people will be checking in a few years. That comes from music being viewed as disposable. The truth is, a lot of people get into hip-hop for the wrong reasons. Personally, I’m not gonna make any records I’m going to be ashamed of in a few years. Not every artist can say that.

Chuck D told me he laments the fact that electric guitar and the saxophone have all but disappeared from Black music. He said it has a lot to do with education and the lack of what people are exposed to growing up. What’s your take on that?

I agree with him. If you’re nostalgic about something that came out two years ago, you need to go back to the drawing board and do your homework. A lot of people are not exposed to the greats. Chuck comes from a real old school era. I’m not that old school. He likes Sam Cooke and all that shit. That’s not really my thing. I’m from the school of Cameo, P-Funk, Rick James and the Minneapolis sound. There was a lot of instrumentation in R&B and funk that had to be tied to the drum back then because everyone was in competition with one another. I’m a student of that era of music, so I understand the importance of quality musicianship. I’ve come to expect it of any genre and it just doesn’t exist in hip-hop anymore. These days, people are really satisfied with two-or-three track songs that might just be a drum machine and some whispering. So, it’s a completely different approach nowadays but I know I demand more from what I do.

How have you evolved as a musician across your career?

The main thing is that I’m no longer at the mercy of what comes out of the machines. Many people who buy pieces of gear go on to sell them or lose interest in them quickly after they’ve exhausted the pre-set sounds. So, being able to program and deal with these machines, with assistance from Bruce Deighton, has become important in creating something unique. Bruce is excellent at getting any conceivable sound to come out of the gear we have available. It comes from doing this for 20 years. As for my political awareness as a musician, I’ve grown in terms of my observations and what I’ve been exposed to by traveling globally and dissecting current events. All of that is incorporated into the material.

Describe how your very pronounced political perspectives have affected you from a business standpoint.

There were more issues with putting out Sonic Jihad than Sleeping with the Enemy. Sleeping with the Enemy was my second album and it featured “Bush Killa” and “Coffee, Donuts and Death” which were pretty incendiary at the time. I mean, “Bush Killa” called for the assassination of President Bush’s father while he was in office. It was a record that had a lot of anger and spoke directly in response to conditions that existed in our community, and the neglect and lack of attention that was paid to us except during the election year. The record kicked up a firestorm of protest and people like Charlton Heston, Tipper Gore and that whole contingent of people were already speaking out about Ice-T’s “Cop Killer,” so Warner Music for the most part shut me down. I ended up putting that record out on my own and it damn near went gold. That provided me with the ability to form my first label called Scarface Records which introduced The Conscious Daughters and got me my distribution deal with Priority Records in ’93. As time went on, I became more and more disgusted with the state of hip-hop and wasn’t feeling the messages that were coming out of the corporate-endorsed hip-hop world, which is what most people are exposed to. I became heavily involved with the financial markets for awhile and then after 9-11 happened, I was inspired to write Sonic Jihad. I put my own situation together that I financially backed on my own to release it. But I had to find a distributor outside the country to be able to release it in the post 9-11 environment of censorship and self-censorship. There was a company in Germany called Groove Attack that made the record available in the States as an import. That opened up the door to have a formal distribution arrangement with my current distributor which is Caroline/EMI. Once that was in place, I began reaching out to people like Public Enemy and T-KASH, who is a former member of The Coup. So, everything is on the move.

Sonic Jihad was one of the most potent hip-hop records to come along in a long time, but it felt like it didn’t get heard as widely as it deserved.

You have to remember the environment at the time it came out. Shit, the cover had an airliner smashing into The White House. So, the Wal-Marts of the world were not going to carry it. Sonic Jihad ended up being much more of a global phenomenon than anything else. In progressive communities, it’s definitely a well-known project. It’s also one of those slow burners. A lot of people are becoming more and more disillusioned with music and entertainment, and want more from it. They’re starting to wake up and reject the propaganda. When they do, they start finding Sonic Jihad, which is really a diamond in the rough for many people that directly mirrors how they feel. It’s a very frustrating feeling to not have somebody speaking for you in your entertainment. Now, Sonic Jihad represents how the overwhelming majority of Americans feel, though they may not feel comfortable saying so. They’re disgusted with this administration’s current direction. Presidential ratings in the 30 percent range don’t lie. So, I definitely know I’m striking a chord with a lot of people.

I was surprised there wasn’t a louder conservative backlash after Sonic Jihad hit the streets.

That’s because they now know I’m not an easy target when it comes to debating. They also know the single most effective way to bury something with a point of view they don’t want out is to ignore it. Back in the day, they would pick on something like what I’d do or what 2 Live Crew or Ice-T would do and the records would sell to the moon and still be available. So, nothing ever changed for the critics except our sales went up. But if the artist wasn’t well spoken, they would put them on these national programs and make fools of them because they couldn’t adequately defend themselves when confronted. However, when you’re talking about illegal wars, propaganda, black-on-black violence or any of these other things that plague society and you have a cohesive argument to back them up, people like Bill O’Reilly don’t try to fuck with you.

Why do you believe there are so few lucid political voices in hip-hop today?

Because you can’t speak on what you don’t know. Analytical, political thought is not encouraged in our community as much as I would like to see it. Many artists nowadays gravitate towards making music they feel labels are looking for and the labels 99 percent of the time endorse the worst in us. They are the ones that are dictating the terms of the street, determining what we get to hear, what we’re exposed to, what kinds of imagery we see, and what kinds of messages get infused into our communities. So, I don’t really fault the artists as much as I do the people who enable the artists. That’s not to say I want every record to be like mine, but Guerilla Funk really does exist to provide a balance where none might not otherwise exist.

Give me some insight into the Guerilla Funk A&R philosophy.

As long as the artist is good, the music doesn’t necessarily need to be polished or top-notch, because we’ll get it there. I look for artists that have a unique voice and add value to hip-hop by saying something of relevance. I also look for the quality of vocals and their willingness to work. The work ethic definitely comes into play because it determines how they’ll be over the long haul with Guerilla Funk. All of these factors come into play. That’s not to say we are signing a lot of established acts either. A lot of times, these are projects we agree to work on. For instance, Public Enemy is not signed to Guerilla Funk. They have their own situation. I just knew that if I was going to work with Public Enemy, it would have to be a project I produce and release on Guerilla Funk. I approached Chuck with that and it was a welcome departure for him as well.

Why do you think hip-hop doesn’t respect its elders like Public Enemy in the same way that R&B and rock audiences do?

Realize that hip-hop is kept artificially young and artificially dumb. Most labels and commercial radio stations have a target demographic of adolescent girls and that pretty much leaves everyone else out in the cold. Ask yourself what musical choices you have available to you in hip-hop once you leave high school. There’s a definite void there. So, hip-hop is not allowed to grow and mature with its audience. People that loved the best of what hip-hop has to offer from my era and even those younger than me have very little to pick from in terms of what’s being offered these days. I know there’s a void there and we do our best to fill it. That’s the situation. There’s no classic hip-hop stations and very few classic hip-hop tours. There’s definitely a focus on keeping the music dumb and disposable, so the next new thing is always what’s touted. The truth is most artists don’t even come into their own musically until a few projects have passed by. It takes time for them to really get comfortable in their skin, gain their footing and realize what’s going on. It’s shame a lot of these acts aren’t allowed to fully develop.

What needs to change in order for artists and the audience to escape corporate-dictated hip-hop agendas?

A lack of reliance on traditional forms of media. Guerilla Funk is really set-up to bypass commercial radio and to operate autonomously in this environment where everybody’s tastes are pre-selected for them by corporations. So, we have a huge mailing list of supporters in the Guerilla Funk community that I can cater to directly online. There is also a huge network of college and community DJs that support what we do in the real world. We have the best of both worlds and it enables me to reach out to folks directly. I can let people know what we have going on and they get it directly from the horse’s mouth. Back in the day, you had to wait until the artist’s next release to find out what was going on with them if you didn’t see them on the road. We now have an almost real-time approach. I can say “This is what’s happening. This album is coming out on Tuesday. Check out the press and come be down with this community. Reject the bullshit you’ve been spoon-fed on the radio and come on over with us.”

I hear you’re considering a Guerilla Funk tour featuring artists from across the label, including Public Enemy.

If we do that, it’s up to Public Enemy’s availability, but they have so much other shit going on. Most of the other acts are down with it, as long as they’re given adequate notice. Chuck has said something about going on the road Stateside in September with all of us. If it happens, the tour will also include Dead Prez, if they’re available, Conscious Daughters, Kam, T-KASH and maybe some of the newcomers like Truth Universal and UNO the Prophet. There are a lot of logistics to take into consideration to make this a reality.

It seems like Public Enemy is more focused on touring overseas than the States these days.

That’s because the response to them over here might be suspect because there hasn’t been a focus on promotion. Overseas, when you deliver a record to a licensee, it’s on the licensee to promote it in their respective region. If I say I’m gonna go do a deal in Japan for manufacturing and distribution, I deliver the masters and artwork to them and they in turn place all the advertising and make the radio play happen. It’s on them to recoup the investment they make by paying me in advance for the ability to carry the record in the first place. In that environment, it takes money to make money. And it takes money to raise awareness. So, of course, the profile is gonna be higher for acts like Public Enemy who don’t spend any money on promotion Stateside, but who are the beneficiary of someone else’s promotion dollars overseas. So yeah, there are more performance opportunities over there than over here.

All of this relates to how well you protect your brand and nurture it. There’s a cause and effect to everything. I still have yet to see the cost of Flavor Flav’s bullshit. I don’t know how that is going to affect the Public Enemy brand moving forward. But Rebirth of a Nation is a damn good record and it’s being put out correctly, with a real promotional campaign behind it. I have television commercials running on all the major networks, print ads in a lot of hip-hop publications, and a unique digital distribution arrangement that places whatever we release on iTunes, Rhapsody and other online services. The only thing we don’t do is videos because they’re damn expensive and there’s no guarantee they’re gonna get played. So, Rebirth is definitely a high-profile project. If it doesn’t fly—at least on par with the other stuff I have going on, given Public Enemy’s name and recognition, Flav’s bullshit is the only thing I can chalk it up to.

What can you tell me about the next Paris album?

Shit, I have no idea. [laughs] I got a lot of stuff backed up that’s ready to go that I gotta release and enable first. I have records by The Conscious Daughters, Kam, Dead Prez and others on the shelf, so I’m trying to make those happen. Then I’ll focus on my stuff.