Donate to Innerviews

Since 1994, Innerviews has provided uncompromising, in-depth interviews with musicians across every genre imaginable. And it does that with no trackers, cookies, clickbait, or advertising.

Your donations are welcome to help continue its mission of highlighting incredible music and artists, without any commercial considerations.

Your contributions will be instantly transformed into stories and videos, and cover hosting and web management costs. Importantly, your dollars will help ensure Innerviews remains absolutely free to all visitors, independent of their ability to financially support it.

Please consider making a donation today by using the PayPal QR code below.

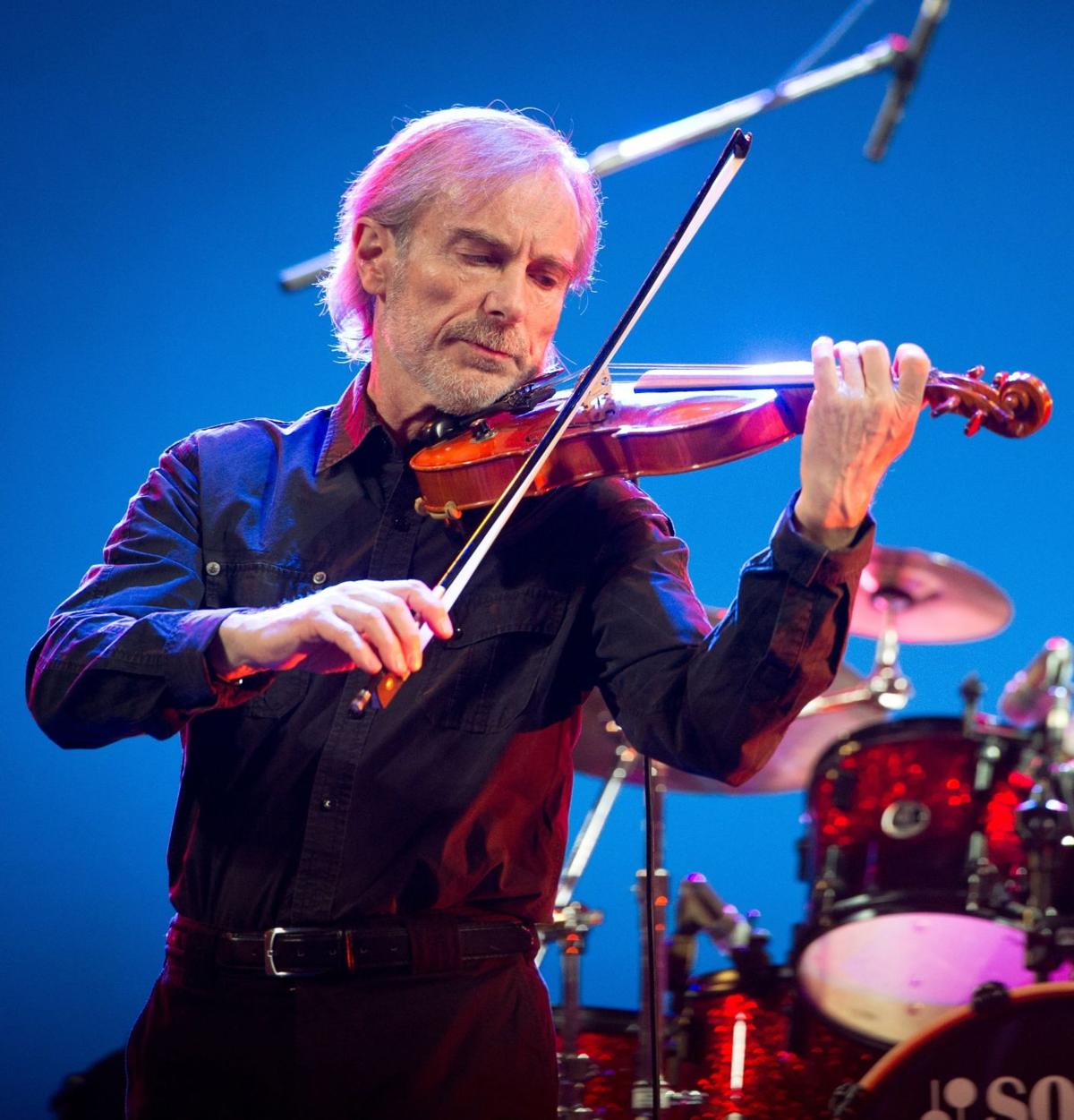

Jean-Luc Ponty

Independent Thought

by Anil Prasad

Copyright © 2002 Anil Prasad.

Jean-Luc Ponty's accomplishments as one of the 20th Century's key ambassadors of the violin stand as a testament to perseverance and purpose. The French musician's place in history as a pioneering influence is assured, having played a significant role in propelling the instrument's profile, both musically and technologically, in the jazz, fusion and progressive rock realms during the last 35 years. Ponty has steadfastly believed in the flexibility and potential for his instrument outside of classical music. He's often gone against the tide by integrating the violin into a wide variety of historically atypical contexts, and experimenting with electronic treatments to create innovative, new sounds.

In 2000, after selling millions of records via long associations with labels such as Atlantic Records, Sony and Blue Note, Ponty arrived at a crossroads that found him reexamining his musical and business tracks. He was approaching 60, looking back on a catalog of more than 25 albums and contemplating how and if to move forward artistically. He was also pondering the best way to work within the confines of a music business with little-to-no respect for the artists who provided it with the consumer momentum to function as a high-stakes industry in the first place.

Ponty responded by forming his own label J.L.P. Productions and launching it with 2001's Life Enigma, his first studio album in five years. The album is hailed as a return to his compositional and stylistic roots stemming back to the critical and commercial jazz-rock successes of 1977's Enigmatic Ocean and 1978's Cosmic Messenger. Having said that, the record sounds very modern, steeped in recent technology, sounds and influences. While his '90s world music-oriented fusion aesthetic remains intact, it's a less busy, more spacious effort with an occasional nod to the techno and ambient movements.

Ponty is no stranger to reinventing his circumstances. After spending the late '60s performing largely acoustic jazz in France, he received a significant break from Frank Zappa in 1969. Zappa composed the music for Ponty's King Kong album, and then asked the violinist to join him as a permanent member of his early '70s recording and touring band. That period also coincided with Ponty emigrating to Los Angeles with his young family.

In 1973, Ponty joined guitarist John McLaughlin's pioneering east-meets-west Mahavishnu Orchestra for several tours and albums including 1974's Apocalypse and Visions of the Emerald Beyond. Atlantic Records took notice of Ponty's steadily increasing profile and offered him a solo deal in 1975. Since then, Ponty has maintained a prominent presence in global jazz circles with more than a dozen best-selling albums and regular touring.

The '90s saw Ponty taking some detours from his well-established solo directions. On 1991's Tchokola, he collaborated with West African musicians during a renaissance of interest in the Paris music scene. And 1995 found him recording and performing with bassist Stanley Clarke and guitarist Al Di Meola in an acoustic trio titled Rite of Strings.

Ponty examined the career and personal reflections that led to Life Enigma, as well as the impact of his '90s projects, in this introspective discussion.

What persuaded you to go back to the style of Enigmatic Ocean and Cosmic Messenger for the new album?

I wanted to go back to my usual style which I started to develop in the '70s and through the '80s. During the '90s, I didn't change as a violinist, but I ventured into projects that were really taking me far away from my own style of music. The first project to do that was the collaboration with the West African artists. Then there was the acoustic trio with Stanley Clarke and Al Di Meola, which was a different type of challenge. Also, in 1996, my wife and I decided we wanted to have a big change of life and move closer to our roots and relatives, so we moved back to Paris. We now live there and in New York, our new U.S. base, part time. We had been living in Los Angeles for the previous 23 years.

The move stirred a lot of doubts and emotions. Both geographically and artistically, I felt it was time to come back home. Therefore, I wanted to create a musical environment for my violin playing that involves using the instrument in a more mature way. Since the '80s, I have come up with a new instrument which gives me a purer sound that's strangely closer to what I was doing in the '60s when I played jazz with straight, amplified violin. So, I'm using less electronics overall, and when I do use them, I want them to be new and up-to-date, rather than sounding like what I did in the '70s and '80s.

The focus is on the writing angle—coming back to my melodic and harmonic approaches, but I was not into nostalgia either, something that was out of the question. It's more about the type of moods I create, so I started creating some which were strongly related to my personality as an individual. I wanted to connect back with that, but I was still hoping to do a production that would sound more modern. That's why it took me so long to make an album. I wanted to make sure I was going to come up with something fresh. I thought it was unnecessary to add one more album to my collection if I was to do exactly what I did in the '70s.

How does the new music reflect your personality as an individual?

It's lyrical, with well-defined melodies. I started as a rather sophisticated musician when I started playing jazz. It very quickly became modern and avant-garde jazz, which then quickly became esoteric—I'm talking about the late '60s here. I thought I was going in the wrong direction. I wanted to express music in a more direct and simpler way—a more lyrical way with some romantic melodies and at times, harmonies, that would be influenced by my classical European background. It's hard to describe because it's not something that's intellectually defined.

In the '70s and '80s, I said I was going to compose music with particular harmonic elements and let the inspiration come. It was more through personal intuition that I developed a layered sound that became pretty personal. I guess my goal or wish—even if it was a bit subconscious—in the '70s was to combine all the elements of music I had personally experienced. I started with classical music, then it was jazz for 10 years, and then I met some progressive rock musicians. So, each time, I was discovering new ways of expressing music which I really enjoyed. During the progressive rock stage, I started experimenting with the tools of the day which were new electric instruments, electronics, synthesizers and so forth. But I wanted to keep improvising like I had learned to do in jazz. And from classical music, I wanted to incorporate more pictorial, atmospheric elements which could be achieved by painting with sound colors. I also wanted strong support like I would have with a symphony orchestra, but since I could not afford to have one, I used different layers of synthesizer sounds. I didn't want to reproduce a symphony orchestra, but I thought it was interesting to use new sounds from the synthesizers in an interesting and satisfying way.

I used synthesizers to have a rich support and rich textures. But in the '90s, I completely went away from that. I was playing with the African musicians as a violinist. I did not want to be too involved as a composer. They forced me into composing and directed me because they wanted me to collaborate with them in terms of writing. Of course, they had the experience of their own music. I didn't, but I was able to relate to some of the rhythms in order to help with some of the melodic elements. But in the end, it wasn't really sounding like my music anymore. Same with Stanley Clarke and Al Di Meola. I was supposed to share in the writing. I brought three compositions in, as each of the other members did. But the pieces had to be adapted to the acoustic trio, so it was a different ballgame altogether. So, through the '90s, with these two experiences and projects, I was an improviser and interpreter on violin. With my own music, I'm a lot more involved as a composer. In fact, Life Enigma has the violin featured more prominently than any other album I've done. On my past albums, I was using the violin as only one of the voices in my orchestration, along with guitar and keyboards.

Despite the parallels that have been made between Life Enigma and the '70s efforts, it sounds much sparser and spacious to me.

That was definitely intentional. I have had a long career with many albums, so I have tried a few different approaches. When I really started producing music, being totally responsible for my albums in '75, this was my first big opportunity to come up with my own concept. Therefore, my first album on Atlantic allowed me to start composing, arranging and producing my own music effectively. Prior to that, I was more like any other jazz musician. I was more of a performer too, having been playing with Zappa and McLaughlin. I started out with adding as much as I could in terms of instrumentation and layers in the studio. I quickly realized there was a limit and it was very difficult to handle live. Sounds cannot be added forever because you end up having sounds within the same audio waves. Somehow, the harmonies start melting into each other. By '78 with Cosmic Messenger, I started to cut down on the number of instruments and layers I used because I realized there was only so far I could go with that.

With Life Enigma, I wasn't even sure I wanted to record another album with so many behind me. One reason I decided to go ahead with it was because my fans via my website were requesting a new CD. I also realized that through the challenging projects I did through the '90s, I came up with a few little, new ways to play the violin. There are technical things in the way I use the sounds that I've never done before, such as the way I treat the sound of the instrument. However, I wasn't trying to prove anything with the new album. Therefore, I wanted the music to be as simple as possible and come straight from the heart. I only included the necessary colors that would add up to the mood of the particular pieces.

In terms of your reticence to record a new album, did you feel you've pretty much said everything you want to say as a musician?

I never quit performing live because you don't necessarily have to come up with a new way of doing things when you do that. You have that experience of connecting with the audience and that's what makes performing worth it. There are many people who first heard me on the albums but didn't always understand what I was trying to say through my music. Once they saw me live, they felt they could understand everything. So, the physical experience of being a performer, experimenting with the music helps. So, since 1996, I never stopped, though I wasn't sure I would record again. I thought if I was to record a new album that I would have to do something a bit different that I had done before. I realized that I had progressed on my instrument and that it was at least worth putting it on tape—a strange thing to say because we don't use tape anymore in this digital age. [laughs] So, that's it. On the composition level, I felt I would not really innovate compared to what I did before, but at the same time, I felt that I had enough novelty to provide through my playing that it was worth putting out a new album.

How did you balance fan expectations for a new album with your artistic leanings?

By doing that—striving for a balance. I was not going to do an album only to satisfy my fans if I didn't feel I could create something interesting. As much as I love to satisfy my fans, because they are the most important thing to me in my career, I put artistic value above everything. Without the fans, what can I do? There is no career. But I needed to come up with something fresh to convince me to do the album. The other reason I wasn't sure about doing another album is because I wasn't crazy about the music business.

I am lucky to have lived during the '60s and '70s during which artists were leading the way and people in the music business such as record companies and radio programmers would follow. It was a time of wide experimentation and the more you dared explore and be adventurous, and came up with something new, the more you had a chance to be appreciated. It was a social state of mind as well. The audience was ready for that. They were looking for new things. It has become a lot more conformist nowadays. It's a big industry and the number one goal is to satisfy the shareholders of these monster companies, though there are still a few people with a vision. It is a very difficult time.

When artists like myself don't fit into a specific category anymore—and I'm not the only one—little, by little, you feel pushed away from the circle of this industrial mentality. I was coming up with albums in the mid-'90s which people at record companies didn't know how to market or what to do with. So, I was a little reluctant to again participate and come up with an album until I met someone who I knew for a long time that used to be in marketing for the majors. He convinced me that I could do my own label. In turn, that convinced me to release the album without any commercial pressure.

Your last contract with Atlantic records only yielded two albums: No Absolute Time and Live at Chene Park. Why?

You're right, yes. Actually, the contract was not so short. It was signed in 1992 and in 1993 I released No Absolute Time. It ended in 1998 after I delivered Live at Chene Park. I had the name of a record company such as Atlantic Records, and the building remained the same, but inside, a lot of people came through and disappeared. When I re-signed to Atlantic, I didn't even know Ahmet Ertegun was still involved. It turns out he was. I signed with Nesuhi Ertegun initially in the '70s. Both he and his brother Ahmet were great supporters. Ahmet was still strongly supporting me to the last minute, but he sold the company, so he's not the only one involved there. None of the people I dealt with when I signed in the '70s are still there except for Ahmet. By the late '90s, I had to deal with people at the label who didn't really understand what I was doing musically. So, we all agreed that there was no need to renew the contract.

What are the risks and rewards of operating at the independent level at this stage in your career?

The risks are financial to be sure, because you have to advance the money for everything yourself. Then you have to wait until it starts paying to gain financial solidity. So, this is not for everyone. It's better to sign with a major for a beginning artist, but when you have the means to do it with a website and have direct contact with a strong fan base, it can work. The other risk is you have to get a distribution deal, but there are few people working on that end. There is a risk of not selling as many albums because of the distribution presence. But the advantage is that I can put out more releases. For instance, I have my first concert DVD coming out soon, as well as a live album recorded in Germany at the Dresden Opera. I'm not sure I could be doing these releases with a major. I would have to present each project to someone in A&R who would have to approve it. Then the people in finances would have to decide if it was worth it for the company to risk its money on the projects. So, I do not have to go through that.

When I was talking to a few record companies before making Life Enigma, some wanted me to do really crazy things, like working with certain producers and doing certain types of music. It's a big reason why I gave up on the majors. But when I finished Life Enigma, I had some offers to sign again with majors. It was a tough decision. I think it's 100 percent more positive to do it as an independent. What finally made me decide to go independent was that at this point in my career, if I am to go on—and I don't know how long that will be, but it should be as long as I am inspired—I don't want to have to get the approval of the record company. I want to realize what I want.

What would make you consider retiring?

I don't think I can retire from the stage. It'd be hard for me to do without it. [laughs] So, I don’t think I can retire really, but maybe from recording. Again, it would be because I feel I have not much to bring anymore or I am doing the same thing over and over again. Also, physically, there's a limit to playing violin. I still have a few years ahead of me if everything goes well and I stay healthy. Stephane Grappelli was a phenomenon because he went on playing almost until the last minute when he was 90 years old. He was playing sitting down and the music he was performing was very mellow as well. I could not go on playing my style of music until I am 90, that is for sure. I would have to switch to a less energetic type of show onstage. But comparing myself to classical violinists, they have to stop when they're between 70 to 75 years old. That would give me another 15 years max to play the violin correctly. So, I am not considering retiring right now, I can tell you that. And since I have started my label, I really have an outlet to release all the fun projects I can come up with.

You turn 60 this September. What does that milestone mean to you?

Sounds old to me. [laughs] I'm surprised to feel the way that I do, even at 59. Of course, I'm sure to young people, it sounds old, but I guess it's not so old as it used to be in previous generations because of diet, hygiene and the environment. I see people around me who are in their 70s and close to their 80s who are in great shape. There has been a little physical decay for sure. I don't go out to party after concerts on the road like I used to when I was young. I have to catch some sleep. But look, I did a tour in the fall and I was fine. I will be fine as long as I don't abuse my system. I am lucky to have good health and good genes. It's all in your head too. As long as you're active and creative and don't think about how old you are in your mind, you can go on a long time.

You've only released two live records since the mid-'70s. Why so few?

One of the reasons is that in America, live albums really don't count much for record companies. It's rare to get airplay on a live album and therefore, they don't like them too much. In fact, in a standard recording contact, it's stated that live albums don't count towards the number of albums you're supposed to deliver. However, in Europe it is the opposite. People are very fond of live albums there. There is an interest in live interpretations. But the new interpretations have to bring something new, because if it's not as good as the studio version, it's not worth it. With the last band I had, the performances are really worth it. The same goes for Live at Chene Park. For that, I regrouped my live band from the '80s who are a bunch of great guys and players. I wanted to have a souvenir of that chapter. I also wanted to record it in Detroit, where the audience is very special to me. The forthcoming new live album was recorded in an opera house. It's very rare for me to be invited to perform in a real opera house and the Dresden Opera is acoustically very good. The audio quality is great. The German radio people who recorded the concert did a great job. The concert was also sold out. All of the ingredients were there for a good album.

Your first live release is your only Atlantic-era album that remains out of print.

The manager of my new [independent] label made an offer to see if we can release it ourselves. Every week I get requests from fans for that album. I don't understand why they don't re-release it on CD. It's funny that they don't want to manufacture it themselves. One of the reasons perhaps is that the jazz catalog has passed from Atlantic to Rhino. Now, Rhino has been bought by Warners. Now, my management has had to deal with so many different people. I hope we're getting close to reissuing it.

I've spoken to several legendary musicians such as Joe Zawinul who are now recording independently or for very small labels. Why can major labels no longer effectively accommodate people like you that are worldwide, established names with strong, dedicated fan bases?

I am lucky that I can find a major label if I want it. Some labels liked Life Enigma. But my thinking is that if I wanted to record with an Indian violinist, it would be a project that may not sell many copies, but it would exist maybe even after I pass away. These are not considerations for record companies. They need to make money right now. Joe and I come from similar backgrounds and went through similar progressions. We are artists who have open minds and come from an era that was open to music with no limits. We went through life in the '60s and '70s when there was a place for us at mainstream radio stations and record companies. When I first visited the States and moved there permanently in '73, there were progressive rock stations in all the big cities. They would play music by Pink Floyd then the Rolling Stones then Miles Davis then Led Zeppelin then Billy Cobham than Joe Zawinul or me. I still remember going to Cincinnati in 1978. My band arrived in town for the Cosmic Messenger tour and a representative from Atlantic said "Your album is tied for number one with Bob Dylan." It was being played on all the important radio stations which exposed our music to millions across North America and the world.

But then, radio formats changed. It became a business as well, once people realized there was big money to be made with music. Big companies started investing in radio stations only to make a profit. In order to do so, they reduced the airplay list to the top-40. Although we were in the top-40 at some point, what they decided was music would sound a certain way all day long. Something that's a little more adventurous no longer fit anymore which affected more than instrumentalists like me. For instance, some progressive rock singers and groups were eliminated. It was crazy, because we were as popular as rock bands a few years before and then, that was it. We were no longer on the playlists. This is what I meant before when I said we were getting pushed further and further away from mainstream music.

It didn't have to be this way because, indeed, we do have many fans around the world. I can tell you that for the past five years, I have been with my group to play in Eastern European countries, Russia and many countries part of the Communist bloc which are now opening to concert tours. It's amazing that our music is known in these places. Although it was forbidden, there were tapes that were making their way around these countries. So, it was also an amazing experience to play things from the '70s and have these people applaud because they recognized them. The young people reacted positively to the music too.

It's not music that has a problem, it's the structure of the music business. It's difficult for record companies to use traditional ways of working an album. They know how to market an album if they can work directly with a radio station—although there are still a few radio stations that have a lesser audience that still support this music. What's really crazy is that we still have a fan base, but the industry doesn't understand that. The Internet has been an incredible tool in this regard, because if you don't have as much access to radio stations or television, there are still ways to communicate worldwide and let people know there is a new album and update them on your career.

Why did you move back to Paris after living in the U.S. for so many years?

It was a bit accidental. When I came through Paris in 1988, I was on tour with my American band in Europe performing at festivals. While in Paris, I was made aware of the presence of musicians from West Africa. In 1988, it was still a fresh situation in Paris, which started in the mid-'80s when some of the most talented musicians from the ex-French colonies moved to Paris because of the language and affinity of schooling there, and also because some of the French music producers discovered some of them in West Africa and brought them over. So, I was intrigued, because I had listened to African music in my youth, but it was more tribal music. I purchased a few recent albums and they were mostly singers. I was curious to meet instrumentalists, since they were using modern instruments such as electric guitar, bass and so on. I was intrigued to see if I could improvise with these musicians, so I came back to Paris two years after that tour in 1990. I grouped a few of them and we started jamming together and the experience was very positive and exciting.

I brought the idea of this project to my label at the time which was Sony/Epic. They loved it and that's how we went ahead with it. I came back to Paris in 1991 to record with these musicians. I was ready to go to Africa if I needed to because I wanted to record a variety of styles from different countries, but the musicians told me that I did not have to because all the best players were already in Paris. So, for the first time in 20 years, I was working in Paris in a recording studio and reconnecting with the city's music business. It was exciting to play with these musicians and I kept two of them in my group—Guy N'Sangue on bass and Moustapha Cisse on percussion. Both were on the 1991 project.

I wanted to move forward from there. I wasn't going to dedicate my whole life to African music. That would be silly, not being African myself. So, I wanted to come back to my own music, but incorporating this new experience, especially on the rhythm side. So, my next studio album on Atlantic was No Absolute Time in 1993 and was a return to my compositional style, but still incorporated the West African rhythm section with several American musicians based in Paris.

From 1993, it became a little complicated to organize tours and rehearsals. I chose to bring my American musicians to Paris and rehearse there for fun, just to be here as a change. But little by little, I reconnected with the music scene. As I went back and forth between Los Angeles and Paris, I realized there were really top young jazz musicians on keyboards, drums, bass and all the other instruments there. That's how my band became comprised of musicians based in Paris. During the '80s, I did not tour much in Europe at all. In fact, there was a very long gap between tours of Europe because I was very busy touring North and South America. Having a band based in Paris suddenly attracted some attention in Europe and I started performing there more and more. After four years of commuting between Los Angeles and Paris, it became too hard. That's when I decided to move to New York part-time, which would be less grueling in terms of flights. So, the reason for moving out of Los Angeles was an unexpected change of direction in my career and music.

Do you feel you've received due credit for your contributions to modern music?

I should not complain because I've received a lot of rewards throughout my life, but it's not constant. There are ups and downs. Lately, there were some downs. I feel I've been extremely lucky as instrumentalists go to have the life and career I've had so far. If you compare yourself to the big stars, it's never enough, but when I consider where I come from and my instrument, what I have lived is like a dream. I never expected to have that much success. I was not even looking for it.

At one point, I was struggling in my late 20s. I was ready to abandon a career in jazz and modern music and do something else. I started knocking on doors around Paris to become an orchestrator or arranger and if that didn't work, I was going to go back to classical music and work in a symphony orchestra because I had come to a dead end. Then, destiny came through George Duke who was coming through Paris. He let me know Zappa wanted to put a band together. That brought me to Los Angeles again after being there quite a few times since the late '60s. That project led to other ones, then McLaughlin, who was aware of my playing. We had met before he hired me.

Once I was based in the U.S., one project was offered after the next. My only hope and the only reason I accepted coming to California at that time was finally getting the chance to play my instrument within modern music. I realized I had something to say on the composing side as well. This meant I could create a musical environment that would be mine. And it was successful. When my first album on Atlantic went up the charts, we started playing clubs throughout America. A year-and-a-half later with Imaginary Voyage, I was headlining theaters. I had to pinch myself to realize it was true and happening to me. When I saw my name at the Greek Theater in Los Angeles, I would look back to where I was coming from and the long road I had traveled to arrive there. So, I've lived some fantastic years and I still do. I still have great moments. The only difference now is maybe, yes, I could say I don't get enough recognition. And not just me, but just musicians in general who deserve more recognition than they get.

Your first LP Jazz Long Playing was recently reissued on CD. How do you look back on the release?

I was happy about the reissue because I forgot how I used to play. The record really sounds like it has a bebop violinist on it. I only played jazz for three or four years at that time. I had a vinyl copy which I could not play anymore because it was so scratched. It came as a surprise when the jazz label at Universal in Paris found it—probably in a closet somewhere. They sent me a few copies of the CD and I was happy because I rediscovered my playing from that era. It was also interesting for me because Life Enigma found me once again developing my sound and working with new instruments as I did following Jazz Long Playing. I've sort of come full circle.

A friend of mine who runs a fiddle-based band believes violinists are the most eccentric musicians around. What's your take?

Not me. [laughs] People who choose to pick up the instrument tend to be different as individuals because of the posture that needs to be adopted and the discipline and dedication required. I guess I was eccentric when I was a young guy. [laughs] I don't really see myself as eccentric, but I can be at times and yes, Nigel Kennedy is eccentric. But behind any eccentricity is a discipline. That eccentricity cannot exist 100 percent of the time. The dedication, concentration and discipline of practicing the instrument is absolutely necessary throughout the whole life of a violinist. To this day, if I'm away from my instrument for a few days, I feel a little bit rusty when I play it again. It's the most difficult instrument in the world to play in tune. So, even if a violinist appears to be eccentric, you're likely seeing a good violinist who is a very serious personality that has something deep going on inside them.