Donate to Innerviews

Since 1994, Innerviews has provided uncompromising, in-depth interviews with musicians across every genre imaginable. And it does that with no trackers, cookies, clickbait, or advertising.

Your donations are welcome to help continue its mission of highlighting incredible music and artists, without any commercial considerations.

Your contributions will be instantly transformed into stories and videos, and cover hosting and web management costs. Importantly, your dollars will help ensure Innerviews remains absolutely free to all visitors, independent of their ability to financially support it.

Please consider making a donation today by using the PayPal QR code below.

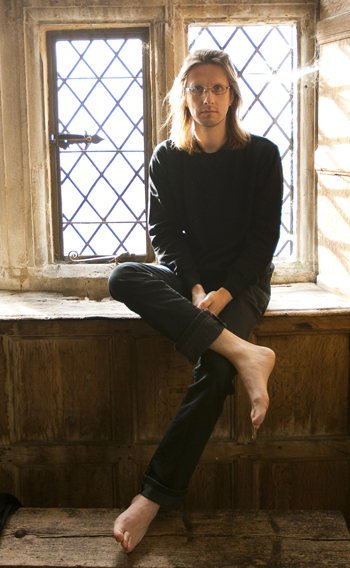

Steven Wilson

Past Presence

by Anil Prasad

Copyright © 2013 Anil Prasad.

Steven Wilson enjoys an enviable set of circumstances. He has total artistic freedom; a circle of elite musician and multimedia artist collaborators; a devoted, global fan base; and sophisticated, forward-thinking management. It’s an ecosystem cultivated over the course of a remarkably far-ranging and prolific career that began in 1982 at age 14 and has since spanned dozens of albums.

The British singer, composer and multi-instrumentalist is best known as the founder and leader of the progressive rock outfit Porcupine Tree, as well as for his work with No-Man, his long-standing art-pop partnership with Tim Bowness. The cinematic rock of Storm Corrosion with Mikael Åkerfeldt and the melancholic pop of Blackfield with Aviv Geffen are two other duos that have cemented and cross-pollinated his appeal across multiple universes. For those interested in diving deeper, a 500-page discography is available, chronicling a dizzying array of output across myriad genres and collaborators.

Wilson’s artistic triumphs have been many, but his new solo album The Raven that Refused to Sing (And Other Stories) is his most ambitious and expansive to date. It’s an unabashed audio love letter to fans of the best of ‘70s progressive rock. It captures the organic energy and borderless, long-form approach of the era and pairs it with Wilson’s omnivorous musical psyche. It’s an album of ever-shifting moods and melodies, dramatic changes, breathtaking solos, and exhilarating rhythms.

Most importantly, The Raven is dominated by outstanding songwriting. It’s a collection of ghost stories that evoke writers such as Edgar Allan Poe and Charles Dickens. The album’s six tracks explore concepts including the spiritual aftermath of murder, the reemergence of voices of the departed, and the angst, regret and obsessions related to coming to terms with lives taken too soon. The album’s packaging features dark, evocative imagery by illustrator Hajo Mueller that adds a surreal dimension to Wilson’s words and music.

The Raven, Wilson’s third album under his own name, is the first to feature his solo band lineup, first established during 2012’s tour in support of his last disc, Grace for Drowning. The group includes bassist Nick Beggs, guitarist Guthrie Govan, keyboardist Adam Holzman, drummer Marco Minnemann, and reedsman Theo Travis. They’re all adventurous virtuosos that lead their own bands and who possess incredibly diverse musical resumes. Wilson recorded the album with the entire group in a single room, performing together in real time at EastWest Studios in Los Angeles.

The facility is the stuff of legends. During its 50-year-history, it has been home to classic recording sessions by The Beach Boys, Ornette Coleman, John Coltrane, Duke Ellington, Elvis Presley, and Frank Sinatra, just to name a handful. To make the most of the environment, Wilson enlisted Alan Parsons to engineer the sessions. Parsons now mostly works as a producer, singer-songwriter and bandleader, but at Wilson’s behest, agreed to bring his revered touch to the proceedings. Wilson was convinced Parsons, the man behind the boards for The Beatles’ Abbey Road and Pink Floyd’s Dark Side of the Moon, was the right choice to record The Raven’s epic suites with maximum warmth and definition.

In addition to his focus on the new album and its accompanying world tour, Wilson continues to serve as an in-demand surround sound remixer. Recent years have seen him rework the majority of the King Crimson back catalog, as well as landmark albums by Caravan; Emerson, Lake and Palmer; Jethro Tull; and XTC. To say Wilson walks on hallowed ground when working on these projects is an understatement. It’s a testament to his sensitivity, comprehensive knowledge of their catalogs, and his own musical achievements that the artists are willing to entrust their recorded legacy to him.

Innerviews met with Wilson, clad in his signature black t-shirt, black pants and sneakers, in the flamboyantly-decorated EastWest Studios lounge. Sitting on an oversized grey couch, surrounded by wallpaper of Pre-Raphaelite women in various states of undress, we began our conversation by exploring the very personal perspectives The Raven’s ghost stories reflect.

During our last interview, we discused the fact that you’re an atheist. Given that, what appealed to you about exploring ghost stories and the supernatural on the new album?

For me, ghost stories are like metaphors. They’re symbols of regret and signify a human soul unprepared to depart because something is unfulfilled in the real world during one’s lifetime. The idea of regret has always been a very potent emotion or human impulse. Getting to the end of your life without being with the one you were supposed to be with; without doing the job you were supposed to do; or without being somehow fulfilled creatively or emotionally is a terribly sad thing to consider. That especially holds true if you’re an atheist, as I am, and you believe you only have one shot to make some sort of sense of life. There are all sorts of incredible pathos connected with the idea of regret.

The big thing about ghosts is how they relate to our obsession as human beings with our impending demise. We are, to our knowledge, the only species on Earth that knows it has a limited period of time. Our mortality is such a burden to carry around, especially if you aren’t happy or fulfilled. Ghost stories are a representation of the Grim Reaper and of the day we will cease to exist. They’re about how mortality feels and how we come to terms with it.

The great ghost stories that inspired me and this record came mainly from the early 19th Century. For some reason, it was a great period for classical ghost stories. If you look at them, they’re about people first and the supernatural second. They tend to be stories about people in relationships or personal situations and the supernatural element is almost secondary. Today, it’s completely the other way around with the sort of Hollywood horror stories out there. The supernatural story comes first, often with a bunch of blank teenage kids that became pawns within it. Classical ghost stories possess a very human, emotional heart, with the supernatural element serving as a dramatic device which amplifies the personal story. The same is true of the stories on this record.

“The Watchmaker” and “The Pin Drop” are akin to modern-day murder ballads. Was that your intent?

Both of those songs feature quite violent murders. “The Watchmaker” is about an elderly couple that have been in a kind of state of paralysis for their whole lives and relationship. It was a relationship of convenience. One day, the watchmaker gets towards the end of his life and just snaps and murders his wife. He then buries her under the floorboards and carries on doing his job, which is about incredibly precise technical work. Then the ghost of the wife comes back. It’s along the lines of Edgar Allan Poe’s The Tell-Tale Heart. The idea of the partner buried under the floorboards continuing to haunt, persecute and nag is related to that. I suppose that does go back to the tradition of the murder ballad in that it’s about a crime of passion and impulses that could not be suppressed or buried forever.

Some people say EastWest Studios has the ghosts of people and projects past influencing it. Did you have a sense of its history affecting the making of the new record?

Possibly, yeah. That’s a very romantic way of looking at it, but the record was written long before I got here. I think the most important thing about the record is that the band was playing together in a room, cutting the tracks live. You could say we walked among ghosts in this studio, but in a more general sense, there’s a spirituality that comes from having a group of musicians interacting in the same space, which I’ve never had before. I’ve never done a record this way. You can talk about ghosts and a spirit, but it’s really about a tangible electricity in the air that emerges from doing it this way. We cut the record in seven days. We recorded seven tracks, one of which didn’t make the record. Each day, we would come in, run through the song a few times, start recording, and after five or six takes, we’d pick our favorite, and do a few overdubs. The next day, we’d come in and do it again for the next track. It was a revelation to make a record this way. I’ve never done that. I’m meticulous and typically spend months doing this. But to have musicians of this caliber and be able to work in this way was very exciting and a bit scary. It did mean letting go of things in a sense and giving up a bit of control.

The Raven features the most complex music you’ve ever written. What inspired you to expand your compositional palette?

The writing is at the highest level of complexity and difficulty I have ever attempted, but I still think the music by complex music standards is still quite simple and accessible. But yes, I pushed myself to write things that were more difficult to execute because I knew I had musicians that could do it. I wrote things that I myself couldn’t play, which I’ve never done before. I’ve always written within my own abilities. Previously, if I couldn’t play the guitar or keyboard part, I wouldn’t write it. For this record, I wrote music that I knew I needed these guys to play. It was a very positive challenge to push myself to create music that is on a higher level.

How do you go about communicating such elaborate structures to the band?

I make demos that are at a very high level in terms of completeness of arrangement. As I said, I couldn’t play the parts, but what I could do with Logic was play things at half-speed to create very specific demos that communicated what I wanted the band to do. Every day, when we walked into the studio, everyone knew the arrangements and parts that were mapped out, in terms of who was supposed to do what and where. Having said that, the whole point of having a group of musicians like this is to not tie them to a particular approach or way of performing. So, things were kind of loose. They had a lot of input, particularly into the solos. In fact, all the solos are their solos. In general, I’m telling them what to play, but there’s a lot of improvisation too.

“The Holy Drinker” is full of wild changes. Give me some insight into the creative process that drove it.

The interesting thing about that song is there are parts in which the band is speeding up. I mean that in a positive way. It’s something I specifically wanted. I think a lot of modern recording suffers from people cutting songs to a click track which keeps the time absolutely rock solid all the way through. That’s really boring. Go back and listen to Bill Bruford on an old King Crimson or Yes record. He’s speeding up and slowing down the whole time. It’s exciting. Listen to Billy Cobham on a Mahavishnu Orchestra album. It’s like a juggernaut heading towards a cliff edge. It has a feeling of momentum and rushing towards something.

For “The Holy Drinker,” although I mapped it out, I wanted it to have a sense of momentum in terms of speeding up and slowing down too. The order of the sections and the arrangement were the most difficult things for me. I can go into a studio and write a bunch of bits, but the trick is organizing them. The interesting thing about progressive rock is that you don’t necessarily have an idea of the shape of the song when you start writing it, because the music can go anywhere. It can be any length and any structure. In a way that’s fantastic, but it’s also a lot of hard work. When my buddy Aviv Geffen from Blackfield writes a song, it always goes verse, chorus, verse, chorus, middle eight, chorus, fade. I’m not saying that’s a bad thing. It’s interesting to work in a discipline like that, but the one thing he doesn’t have to think about when he writes a song is the structure. Instead, he concentrates on the melody and the hook. When you write a piece of art rock or progressive rock, or whatever you want to call it, everything is up for grabs. You want to create the feeling of a musical journey that is satisfying and logical. It’s similar to a movie script in that you’re trying to find the right order of the scenes so the narrative will unfold and peak at the right time.

Intriguingly, Adam Holzman wrote out some parts from your demos prior to the sessions.

Yes, he did that for things like the piano part in “The Raven.” I played all of that on a MIDI keyboard. He’s a guy that reads and writes music, so he wrote it all out. It made me feel like my music is proper music. [laughs] When you see your music written down by a musician that reads and writes, it makes it more legitimate somehow. There’s something about seeing your music on a sheet of paper with dots. I don’t read and write music, but when someone else transcribes my stuff, it almost makes me feel like a proper composer.

How has the band’s chemistry evolved since last year’s Grace for Drowning tour?

We started touring last October and it has been amazing. The band is a real band. It seems like an obvious thing to say, but it wasn’t necessarily that way to start with. Basically, I brought together a group of musicians who had never played together before, and not only that, but they came from two very different traditions. I began with Adam Holzman and Theo Travis, who are basically jazz musicians, and Nick Beggs and the original guitarist Aziz Ibrahim, who were rock musicians. Marco Minnemann is somewhere in between. There was no guarantee the musicians would coalesce into something satisfactory. It wasn’t until I literally stood on stage at the first show, even though we rehearsed for a week and worked very hard to put it together, that I thought it would work. There has to be a certain amount of serendipity and luck involved. These seemingly disparate individuals came together to play my music in a way that almost immediately transcended the studio versions. The songs felt like living, breathing things. I was so excited and inspired by how the band sounded live. It sounded like everything I always wanted to do with music, in a way. From that point, I decided “Okay, I’m going to write an album for these guys to play.” A year later, we’re sitting here where we made that record.

Describe your bandleading philosophy.

In this group, I can be more of a musical director. I flatter myself by making a comparison with Frank Zappa, but he is the role model here. Zappa always had musicians in his band that were better than him, but he was the guy with the ideas. I don’t mean to put great musicians down, but one of the things that saddens me about fantastic musicians is that sometimes, when they’re left up to their own devices, they end up making jazz-fusion that no-one wants to listen to except other musicians. I’m generalizing, but it’s largely true that great musicians left up to their own devices don’t seem to do anything very interesting. I feel arrogant enough, if you like, that I feel I have something I can bring to the table. I wrote these songs. I couldn’t play them in a particularly inspired way, but I felt if I gave these great musicians strong material that we would have something very special. I have a role in that and they do too. Zappa surrounded himself with guys who wouldn’t necessarily make particularly interesting music on their own, but were absolutely fantastic when they were given strong raw material to work with. In a way, that’s what I always wanted to be. I never wanted to be a guitarist or a singer. I wanted to be someone that wrote and produced records. It has come full circle. I’m back to almost removing myself from the performing side, thought not completely. I still play guitar and keyboards, and I’m obviously the lead singer, but I’ve removed myself from a lot of the responsibility of performing the music like I do with Porcupine Tree.

Is it at all intimidating to know that one of Holzman’s previous bandleaders was Miles Davis?

I try not to dwell on those things, because they’d blow your mind. [laughs] It’s not intimidating though, because Adam doesn’t make me feel intimidated. I see Adam as someone who has a genuine passion and excitement for playing this music. I don’t get any attitude from him or any of the guys. They’re all extraordinary musicians. But you know, I’ve had this situation so many times in the last few years, being in the studio with Robert Fripp working on the remixes of King Crimson’s In the Court of the Crimson King and collaborating with Ian Anderson on Jethro Tull’s Aqualung. There have been moments when I could have just said “What the fuck am I doing? This is absurd. I’m working on a record I grew up listening to!” Those moments have happened a lot in the last few years and it’s incredible. I’m not saying I’ve become blasé about them, because I think it’s incredibly exciting and never becomes boring. But at the same time, I’ve come to accept that those things are happening to me now.

Why do you think those things are happening to you?

Because no-one else is doing what I’m doing. I’m not saying what I do is particularly good or bad. People can make up their own minds about that. But if I objectively step out of the situation and say “Who else is doing what I’m doing?” there really isn’t anyone else. In a way, I wish there was. What I mean by that is someone who is bridging and engaging the original generation of progressive music while still making records himself. There are still guys working on the old stuff and there are a lot of new bands, but there aren’t a lot of people bridging the two. I think that’s been a reason why I’ve had the opportunity to do what I do. The guys from the older generation come to me because it seems like I’m the only one doing it. Actually, that’s not entirely true in that Jakko Jakszyk is also now doing a lot more surround stuff. But I’m very lucky to be a big fish in a small pond.

How did Alan Parsons’ presence inform the sessions?

Alan was hired to be the engineer. The thought process was that I wanted to make a record that had a quality associated with a lot of the records I was remixing. I began to understand more about what I love about those records when I experienced the electricity you get from a group of musicians playing together in a room. Beyond that, there’s a tonal quality—almost a “golden warmth”—that people talk about when they discuss classic albums from the ‘70s. A lot of that has to do with the expertise of the people recording the albums back then, which I think is largely a lost art. I think there are still some guys working that were making records back in those days. I looked at some engineers and some weren’t available. Some had retired.

In the back of my mind, the one I really wanted was Alan, but it never occurred to me that we could really get him. I thought “There’s no point trying, because he’s not an engineer anymore. He’s a performer and producer now.” We got to a point where I said “Why don’t we try? You never know.” Luckily, he knew who I was and was already familiar with some of my surround work. He wanted to do it and he was wonderful. The one concern we had was “Is someone now known as a producer going to be able to go back to just being an engineer?” And he did. He was fabulous. He deferred to me because I’m a control freak. I’m not good at giving away. He had excellent ideas and was quite prepared to have me poo-poo them if I didn’t like them. There were no ego issues. I totally trusted him. We were there for a week with the musicians and I had to make sure everything was going correctly in the live room. I was supervising as a musical director in that respect. I just left it to Alan to record everything. If I heard anything I didn’t like when I came back to the control room, I would say so. To be honest, I hardly had to. It sounded good. It had the quality I wanted. I didn’t want the record to sound pointlessly nostalgic, but I wanted to have more of the vintage tones I associated with the early ‘70s and Alan was getting them. He made the record sound great. It was exactly what I needed out of the experience.

Gentle Giant’s Derek Shulman attended the New York playback session for the album and jokingly said “Where’s the single? Where’s the radio hit?” Do you feel you’ve completely transcended the notion of commercial pressure in your career?

They don’t call it a single anymore, rather it’s a focus track. You can still generate a whole career based on one song as Lana Del Rey proves. But I’ve been doing this for 20 years and I’ve never had a breakthrough song. I’ve never had a song become a key track. I can look back at some of the Porcupine Tree songs and say “They should have been radio hits.” I’m talking about things like “Lazarus,” “Trains” and “Shallow.” If they had been done by another group, they might have been hits, but I don’t lose sleep over that anymore. It has been about gradually building and building through continuing to make hopefully quality albums. I gave up even thinking about singles. I don’t even know what a single is anyway. I guess subconsciously I understand that a single is something short with a verse and a catchy chorus that can get played on the radio and that your mum can sing. Those aren’t the kinds of records I listen to. It sounds like a pompous thing to say I’ve transcended that, but rather I’ve kind of moved sideways in that it doesn’t even for a second concern me when I’m doing a record. After we’ve finished a record, I’m quite happy to sit down with a record label and say “What can we do to promote this record? Is there a song we should do a video for? Is there a song we should service to radio?” But that won’t enter the creative period.

Do you feel anything is possible for you going forward?

Pretty much. I’ve felt that for awhile now. I don’t have a particular master plan or career plan. I never really have. What’s important is that everything I do be interesting to me. I think a lot of musicians say that, but don’t actually do it, and I really do. It would have been so easy for me to have done another Porcupine Tree album after The Incident. We were told that the next record was going to be the “big one” and that the next tour would gross $5 million. We had just sold out Radio City Music Hall. But I was bored. I didn’t want to do it. I wanted to do something different. I went back to playing smaller clubs, performing with a new band and losing money every show. But it was so fulfilling creatively. It all comes back to what we were discussing at the beginning—the idea of not wanting to regret that you didn’t do what you should have done when you could.

During your solo tours, you’re a completely different performer onstage than you were with Porcupine Tree. You’re animated, smiling and clearly having a lot more fun. What accounts for the difference?

One of the reasons is that I’m not so tied into the instrumental performance side anymore. I can be free for the first time ever. I can be a real frontman. I think I’ve always been limited in being someone who can be a frontman in Porcupine Tree because I had to tap dance on my guitar pedals and play lead guitar and all that stuff. The other thing is the band is so fucking good and I know it. To have a band like that behind you makes you feel so confident. I feel like I’m top of the world. I’m not saying Porcupine Tree isn’t a great band too. It is. But when I’m standing in front of the guys in my band, I know I have the best fucking group on the planet right now. That gives me a feeling of invincibility and I think that comes across. Also, I think with every tour I’ve done, I’ve felt a little more confident about myself onstage. I never wanted to be a frontman, particularly. It was very uncomfortable to start with, but I’ve learned to enjoy it more and more with every tour. Another element is my own tours have been more of a show. I’m not saying what I do onstage is choreographed, but I feel more like an actor. Take “Index” for example. We’re behind a screen during it and it’s almost like a set piece. I’m kind of a part of that visual experience.

In general, there’s a sense of newness. One thing I think fans sometimes have difficulty understanding is that one of the exciting things about being a musician is you have the opportunity to work in many different configurations with many different musicians from many different backgrounds and countries. I realize it’s unusual to do that. Many rock musicians have a career consisting of being with the same group for a whole career. If you look at the jazz world, that’s not the case. In jazz, you’ll play with many different configurations over time. You’ll be constantly changing the people you work with. It won’t be a monogamous musical situation. In the rock world, people expect you to be monogamous and be dedicated to the same band. That’s actually not a very healthy musical approach—at least to me. I’ve got to the point where I’m at least halfway through my musical career. I don’t want to be doing album after album, tour after tour with the same people. The gift of being a professional musician has more to offer than that.

You’ve pretty much defined the special edition physical package concept for the progressive rock genre, to the point where it’s practically expected that every major album will have a deluxe edition with additional bonus content on it. Is it a healthy thing to be conscious of demos and outtakes—things that would have been tossed aside in previous eras—as marketable fodder during the creative process?

I think these days the demos, which would never have been heard in the past, have now become part of the release strategy. You release the demos, the instrumentals and the masters all at once. I think you can look at the world of cinema as the precedent for that. You have DVDs come out with the behind-the-scenes documentary, the director’s commentary, the outtakes, and the deleted scenes. Those guys have been doing that for 15 years.

If you took the majority of those directors aside, they would tell you “I wish we didn’t have to do any of that and could just release the film on its own.”

I guess I feel that way a little bit too. There’s something very appealing and romantic about simply releasing the musical statement and not having to flesh it out with a lot peripheral extra tracks. But the world that we live in demands context and background, as well as extra value added to the package. I don’t hate it. I’m quite proud of some of my demos in their own right. In a way, the difference is now those things become available the same day the album becomes available, whereas with these special editions of classic albums, those demos come out 40 years after the album originally came out. I think King Crimson was one of the first bands to create a deluxe anthology box set. The 1991 Frame by Frame and 1992 Great Deceiver box sets are really the precedents. Robert Fripp and Declan Colgan at Panegyric have always been into creating these archival collections. I rise to the challenge of making interesting special edition packages. Also, the Blu-ray disc is interactive. So, you can be listening to the album and then flip over to a demo version, an instrumental, watch a video, read the lyrics, or see pictures of the band cutting the track in the studio.

What does it take beyond money to get you interested in a remix project?

I’ve got to love the album and people involved. It’s as simple as that. I get invited to do a lot of stuff, believe me. I did two Emerson, Lake and Palmer albums, but I’ve chosen not to do any more of their records because I can’t honestly say I love them. I didn’t feel as connected to them as the King Crimson or Jethro Tull albums. So, Jakko Jakszyk will be doing the next two for ELP and he’ll do a great job. Going forward, I’m only going to do things I genuinely really, really love. The main thing about doing them for me is what I learn from the process. I really have learned a lot from working on these records. I absolutely love the King Crimson, Jethro Tull and XTC records I’m doing now. I grew up with them. I know those records better than the bands do. That’s an obvious thing to say because those guys haven’t listened to most of those records since they made them. No-one listens to their own records.

What are the general philosophies you bring to the table when you take on a remix project?

I’m trying to remove myself from the process by making the mix as faithful as possible to the original stereo mix—assuming the original stereo mix was a good mix. I’m trying to make it sound clearer, with more sonic definition. Those things tend to happen by default anyway, just by having the masters and not having to go through the analog stages. The bottom line is when you mix albums through analog boards onto analog desks, there are lots of compromises. Lots of details are lost in the sound picture. What I’m doing is going back to the master tapes without going through any of those analog processes. That’s why the King Crimson Larks' Tongues in Aspic remix sounds so much more vibrant, exciting and dynamic, while remaining quite faithful to the original. If you analyze the stereo picture, the new stereo mix is very close. The EQ, balance of instruments and effects are very close, but somehow it sounds more upfront, powerful and detailed. The surround mix is where I get to put more of my stamp on things. I have a way of doing surround which is very much intuitive. I just think about how I would want to hear things and people seem to like it.

What are the bigger challenges you face when working on an album remix?

Not letting down people that know the records intimately. The bottom line is that there are always going to be people who are disappointed. There will always be someone who will hear the remix as alien because it doesn’t sound the same. The challenge is to somehow capture the essence of what people loved about the original mixes and not make the album sound modern for the sake of it. My goal is to provide a different perspective on things, and I realize all of this sounds very contradictory. Therein lies the rub. Somehow, I have to marry these completely contradictory things when we’re recreating the mix to make it sound better, yet not change it. I’m trying to strike a balance between all of these things.

If you could remix any albums by any artists, no matter how improbable they might seem, what would they be?

Electric Light Orchestra’s Out of the Blue, which is the first album I ever fell in love with as a kid. It’s still one of the greatest pop records of all time. There are the really obvious things like The Beatles catalog. Apparently, those remixes have been done, but they haven’t come out because no-one can agree on them. I’d love to approach the Led Zeppelin and Pink Floyd catalogs. Talk Talk’s Spirit of Eden and Laughing Stock would be fantastic. We were close to doing them until Mark Hollis decided he didn’t like the idea of them being remixed. Those records would lend themselves to surround so well. Also, there are more obscure things like Arvo Pärt’s Tabula Rasa and Steve Reich’s Music for 18 Musicians. Imagine how amazing Reich would be in surround with all of those polyrhythms. I don’t know how much of a market there would be for those things, but they’re of interest from a personal point of view.

What reissue projects do you have on the go for 2013?

Yellow Hedgerow Dreamscape, some of the earliest Porcupine Tree recordings, is being reissued on my own mail order label this year. I don’t know when, but possibly towards the end of the year. Porcupine Tree’s In Absentia turned 10 years old last year. It’s 11 years old this year. We’ll reissue that as a special edition with a Blu-ray disc featuring the video material we have. There were a lot of other tracks recorded during those sessions that didn’t make the album, like “Meantime,” “Drown with Me,” “Chloroform,” “Futile,” and “Orchidia.” We’re going to bring all of those together, perhaps along with some instrumental versions and demo versions. It’ll be an all-singing, all-dancing experience. [laughs]

Last year, you stepped away from Blackfield as a full participant, preferring to let Aviv Geffen lead the project. What’s your involvement in the group’s forthcoming album?

I’ve ended up singing a couple of songs on the album, which is a lot less than before. Aviv’s got a bunch of great singers to contribute to the record, some of whom are quite well known. I’ve played some guitar and mixed it. I’ve also done a surround mix for Blackfield for the first time. Aviv never liked surround before, but he relented this time for some reason. The last thing I would ever want is for a Blackfield album to come out that didn’t continue in the quality and tradition of the previous albums. I think this upcoming one does.

Do you feel the fan base will accept Blackfield as a touring entity without your involvement?

I don’t know. I hate to give Aviv this problem and let him down. He wants Blackfield to be the kind of band that makes a record every couple of years and goes out and tours hard. I felt guilty for so long that we weren’t able to do that. I think he needs to find someone who can commit more to it, because he’s got a lot of ambitions for the group. The new songs are great. I think a lot depends on who Aviv finds to fill my role onstage as a singer and guitar player.

How do you look back at your days in Karma, the progressive rock band you started when you were a teenager?

Karma was what you would now call a neo-progressive rock band. When I was a 14-year-old kid, I discovered Marillion. They were local lads. I could go see them play in local venues and loved it. A few of us 14-year-olds started this band which sounded a bit like the bands we liked from our big brothers’ record collections. It was a step in the learning process. I think today, the music I make is related to an earlier era of progressive music, especially when you look at the importance of jazz in the equation. Jazz is something very specific to the first generation of progressive rock. It almost completely disappeared in the generation that came after. Marillion, who I love, and bands that came after it, completely removed the element of jazz and replaced it with more of a pop sensibility. I think Marillion did that better than almost anyone else has within the universe of progressive rock. Jazz wasn’t a part of Karma either.

I love that first explosion of creativity that came to be known as progressive rock. No-one ever referred to it that way back then. That first generation of musicians grew up as classical and jazz musicians and suddenly discovered the possibilities of pop music. It was a one-time situation that could never be repeated, because now, everyone listens to Led Zeppelin, Pink Floyd The Beatles, The Beach Boys, and The Doors. Everyone knows that stuff, including classical and jazz musicians. But during the emergence of this genre, for one brief moment, we had musicians who started playing pop music that grew up entirely outside of that genre, existing almost exclusively within classical and jazz. Suddenly, they were working on music with no map. They didn’t really know where they were going. They were just doing what came naturally, which was bringing their chops and love of Mahler and John Coltrane to pop music. I loved that whole collision of influences and cultures at that time. And that’s where I’ve arrived with my own music. I’m trying to recapture that feeling in what I do today.

Alan Parsons on Engineering The Raven

What attracted you to working on The Raven?

Steven’s reputation. I had also heard his work with Porcupine Tree, previously. I was interested in the fact that he told me he was looking for a retro sound, perhaps something reminiscent of the early ‘70s. Above all, he said that the band was going to play live, together. That’s really what clinched it for me. I thought “Oh wow, this is definitely for me. I want to be involved in this, because that’s how I work too.” I’ve always maintained that a band playing together and bouncing ideas off each other is the way it should be.

Describe your role on the album.

I’m too modest to say I had any huge creative input, other than the way the sound was constructed. It was a very nice relationship. The band looked to me for advice on sound and balance matters. The drums were the most critical thing to achieve the right balance and textures for. The dynamics of Marco Minnemann’s playing were very challenging. I was constantly in awe of his playing. I think we also got some unusual bass sounds happening—bass sounds I would never have gone for, had they not coaxed me into it. They said “Make it sound like Chris Squire.” [laughs] So, that’s what I did. I think that’s fairly obvious on the first rack “Luminol.” To make that happen meant I used a Marshall guitar amp to record the bass. I haven’t recorded a bass through an amp for a very long time. Normally, I record it directly straight out of the instrument. It ended up being a great bass sound and I’m very proud of it. The whole band is just incredible and mutually respectful of each other’s abilities. I was in heaven. I said “My God, how could I ask for a better band of musicians to record?”

What were some of the challenges you faced when working on the album?

They made it really easy for me, but there were a couple of challenges. Theo Travis was standing in a little box in the corner of the studio. It wasn’t hugely well-isolated, so I was picking up quite a lot of the guitars and drums, especially given that Marco is no quiet player. [laughs] He’s really hitting those drums. So, there were some issues with leakage into the sax and flute I had to work on. Also, when Adam Holzman was isolated in the room on the far end of the studio, he was playing piano, as well as electric piano. The electric piano was being played very loud through an amp. My job was to make sure one set of mics was muted against the other.

What were your impressions of working on the album at EastWest studios?

Working on Steven’s album was the first time I’ve been there. When I walked in there a few weeks before the sessions and saw the Neve board I said “Oh yes, I can work with this.” It’s a ‘70s classic Neve console that’s been brought up to date with flying faders—automated faders that move up and down on their own, according to what you tell the computer you want them to do. That wouldn’t have existed on the original version. It could be argued that automated consoles aren’t necessary anymore if you mix, as we say, “in the box.” These days, all of the volume and EQ changes are done inside the computer, so you don’t have to physically move anything at all. But for me, it’s still nice to have the touchy-feely thing and be able to push things up and down manually. It’s much better than clicking a mouse and doing things one track at a time.

The album is available in Blu-ray format. What’s your perspective on its value as a high-resolution sound carrier?

Blu-ray audio is great. I think Steven did a great job mixing it in surround. I wish I could have been involved with that, but you can’t have it all. [laughs] I’m so pleased that Steven has the reputation he does for surround. As much as I like Blu-ray, I’ve never been that unhappy with CD. It has become better over time and with that improvement has come a higher ability for the average person to discern sounds. When CD first emerged, everyone said “Oh wow, this sounds incredible. There are no scratches or crackles. It’s the best thing I’ve heard.” But when we got tuned in a little bit more, we started realizing “There’s something not quite right in the mid-range” and this and that. I do believe with the technology improving, our ears are too. Blu-ray and modern digital conversion technologies are making a lot of difference. Having said that, here we are in the MP3 and earbud world, where so many people don’t care about audio quality. It’s nice to know that there are some people that do still care.

Do you consider the Wilson album within the same canon of the other classic album projects you’ve worked on?

I think so. If there is any justice, this album should do incredibly well. It’s a beautifully composed and constructed record. I think the quality of the songs, the lyrics, and Steven’s performances as a singer are really super. The musicianship and solos are just second to none.

Adam Holzman on Collaborating with Steven Wilson

What was your initial reaction when you heard Wilson’s demos for The Raven?

My initial reaction was I wanted to play this stuff right away! Actually, I was a little surprised at how overtly “proggy” it was. The demos for “Luminol” came first and it was clear Steven was drawing from a larger canvas than previously. Grace for Drowning had a really powerful vibe, and at first I was concerned that, though we gained a lot in energy and complexity, maybe we had less of the ambient “mood” thing happening, which can make the whole thing more heavy. I’m glad to say I've been proven wrong. The Raven, I feel now, is a more direct and powerful statement than Grace for Drowning. Although the demos contain many of the elements that made it to the final versions, the music really came alive when the whole band played it live in the studio.

Describe how the keyboard parts Wilson included in the demo mapped to your personal leanings.

“Luminol” had several sections that feature things I gravitate towards. The Rhodes/ring-mod bit near the top, for example, was something I first did on the live version of a song from Insurgentes titled “No Twilight Within the Courts of the Sun.” Steven incorporated a similar idea into “Luminol.” The distorted Rhodes solo is home turf for me, of course, and I loved the opportunity to contrast that with a quieter acoustic piano solo in the same song. Also, the Minimoog solo in “The Holy Drinker” was something I'm glad he worked in. I think he knew I was chomping at the bit to do something like that.

You chose to write out some of the music in advance of playing it. Describe the impetus to do that.

For me, it's part of learning the music and mapping out the general scheme of things. I was planning out parts and trying to remember everything. One thing I should mention is all of the solos are completely improvised, with the exception of the Rhodes solo on “Luminol.” That was something I had to break down and figure out what to do, more so than usual. It has an alternating 4/4 - 15/8 pattern, and the bass line was tricky to match harmonically.

How do you feel the band’s chemistry has evolved since you joined it?

When we first started rehearsals for the Grace for Drowning tour, the sound of the band came together very quickly. Playing all of this new material was a buzz for everyone involved. I had worked with Marco on another project previously, so he and I already had good communication going in. I think Steven also dug the fact that Marco, Theo and I don't play the same thing every night. We're always going for variations on a theme, within reason, of course. So, that added another spark. I’ve done a lot of touring over the years, and I must say, I haven't been in a band that hits the mark so strongly every night. So, the transition from something like that to the studio is actually fairly easy. Once a band has a life of its own, when you walk into a good studio, the music literally explodes out of the studio monitors.

Wilson has said one of his key interests in his solo career is infusing the technicality of progressive rock with the spirituality of jazz. Talk about the bridge you hear being explored on The Raven.

That's a heavy statement, and I am with him 100 percent on that front. The thing about jazz is this: it’s always in search of a moment of magic, in which something special and unexpected happens. The best is when something clicks and no one person can take credit for it. Obviously, there are sections in jazz where things are purposely left up in the air—anything from a solo over a few choruses to playing completely free—so something that is not rehearsed is still allowed to happen. I think the spiritual element comes in when you are always reaching for that “something” beyond, in the heat of the moment.

I love prog too, but a lot of prog is just about making the notes, and the forms are completely locked. The musical elements are very dense, as well. There is less room, harmonically and structurally, for the magic to happen. With prog, in many ways, the “moment” happens when you write the music, or first record it. On the other side of the spectrum is Miles Davis, who used minimal musical motifs—sometimes just a key center, a bass line and a fragmentary melody—and what happens is one big chance to create. For better or for worse, that's the risk.

I can understand and get behind both approaches, which Steven's gig requires one to do. Steven has left gaps in the music in which something different can happen from night to night, but we still have to deal with a lot of specific parts as well. Also, Steven's music is more dependent on vibe and mood than most other progressive bands, and that also strengthens the connection to jazz and improvised music.

How would you compare Wilson’s bandleading approach to Miles Davis, who you played more than 200 gigs with?

Probably the biggest similarity is their determination to grow and change as artists over the years, no matter what the critics or the public say. Both Steven and Miles trust the musicians in their band and give them a lot of latitude. Also, both of them have very eclectic tastes. As for differences, Steven will come in with a song and a complete picture of what he wants to do, and we all embellish it and make suggestions, but it's all still basically Steven and it doesn't change radically. Miles would bring in an idea and, using his band members as a big paint brush, shape the music in rehearsal and on stage over time. The end result might not sound at all like the initial idea.

Tell me how Alan Parsons contributed to the sessions.

Not many engineers or producers know how to record a band live in the studio anymore. It’s becoming a lost art. Most engineers record one instrument at a time. That's how most records are made these days. So, to have someone that knows how to fire up a whole band in the studio all at once, and have great sounds happening on all of the instruments, is inspiring. Also, his experience and influence in connection with records like Pink Floyd’s Dark Side of the Moon made him the perfect guy for this project.

Alan used classic micing techniques on the drums, using fewer mics than you might think for a full, rich sound. We miced the piano several different ways in the course of the project, again using fewer mics than usual and not very close, letting the space itself play a role in the sound. We sometimes ran the Rhodes and Hammond B3 through a distorted guitar amp, to add an extra edge.

What do you envision as the future possibilities for this lineup? Is the sky the limit?

I hope so. Personally, this band is right where I want to be, musically. I look forward to seeing where Steven might take it from here. It would be great to do another studio album fairly soon and really establish the band's identity. In the end it is Steven's vision, so I can't really guess what might happen. That's part of the fun, I suppose.

Theo Travis on the Creative Process behind The Raven

What were your thoughts when you first heard Wilson’s demos for The Raven?

I thought they sounded fantastic. I particularly liked “The Holy Drinker” and “The Watchmaker,” but all the songs are great. Having worked on so many of Steven’s albums, including all three of his solo albums, I am used to the incredibly high standard of his work, so the fact that the songs were strong was no surprise to me.

Wilson wrote the album specifically with the musicians in mind. Describe the sections and parts he envisioned for you and how you ran with them, using your own voice.

I played solos over various sections of various songs, some of which were used and some of which were not. Some of the tracks were works in progress when I originally played on them or on the demos. Steven would say “Try something over this section” and see how he liked it. He knows very well what I do and sometimes I would try solos on different instruments to see how they sounded and fit on the track. Steven would often give direction like “Play wilder,” “Play sparsely” or “Try some long notes.” It was quite an organic process and pretty relaxed. There were some clear sections for me in which Steven had a definite plan for which instrument he wanted me to play—for instance, the flute solos on “Luminol.” I would play a few solos and then we would have a cup of tea. He would then go away and choose his favorite.

Much of this band’s success has to do with its chemistry. What are your thoughts on what makes it work?

The chemistry was established very early on at the first U.K. rehearsals. It was very exciting meeting everyone in a rehearsal room and playing the music together for the first time. All the musicians are absolutely fantastic and very professional, including all four guitarists who have been in the band. So, they were and are easy to work with. Adam Holzman is the other jazz musician in the band, so we have a certain way of working and approach to playing and improvising in common. The good chemistry was the same during the recording sessions, too.

What’s your perspective on Wilson’s approach as a bandleader?

Steven has very clear and strong ideas about his music. There was quite a bit of pre-production before the sessions and his demos were as good as many people’s finished tracks. He knows what he is after and can decide quickly if he’s not liking what he’s hearing or if he’s looking for something else. However, he would often be open to ideas and willing to try things out to see how they sounded. Steven was always open to input from the musicians as to which takes people liked and which solos they felt best about. Steven is an excellent bandleader as he knows what he wants, but is down to earth and does not have a huge ego.

What was Alan Parsons' influence on the sessions?

I think Alan’s input was largely in the placing and use of mics and the getting sounds from the room to “tape.” He started at Abbey Road in London and is very skilled in recording techniques with bands playing live in the studio, which is what Steven was after. There were some specific things he suggested, like the seagull effect from plugging a guitar into a wah-wah pedal the wrong way around. That was something he did with David Gilmour on Pink Floyd’s “Echoes” and Steven used it somewhere on “Holy Drinker.” He also had his own way of using two mics to record the flutes and saxes, which worked well.

How do you feel the album turned out?

I think it’s great, but then I thought Grace for Drowning was great too. I also love Steven’s Bass Communion project, as well as much of what he has done with Porcupine Tree and No- Man. I think Steven is constantly refining and honing his skills as a writer, singer, producer, and artist. He just gets better and better.

Nick Beggs on Something or Other

How did you react to the initial demos for The Raven?

I like to prepare for all projects by investing in new stage clothes. When I have the right outfit, I'm ready to record. So, it was off to my local J.C. Penney where I found some suitable slacks and a golfing hat. That established, I turned my hand to more pressing matters. What fabrics are in this year? I discovered that brocade is a hot favorite with the “prog-noscenti” and elected to invest in a pair of black riding breeches. Once back in the studio, listening to the demos and wearing my new pants, I shat myself.

What sort of direction did Wilson gave you in the studio?

In the studio, Mr. Wilson was most emphatic that I change my attire as the aroma was affecting the occupants of the other studios by way of the air conditioning system. Naturally, I was most accomodating and relaxed in a mid-priced trouser suit from Macy’s. He didn't like that either.

Describe Wilson's approach to rhythm.

Mr. Wilson is a very good ballroom dancer and tutors the ensemble personally. Presently, we are preparing something for the upcoming tour, but I'm not allowed to discuss it as it could result in me being branded with hot coals.

Tell me how you and Marco Minnemann collaborated to create the underpinnings for the pieces.

Marco usually constructs a rhythmical hypothesis from which it is my duty to extrude a bass motivation. Once the bass motivation is extruded, the underpinning can be undertaken. But I must stress no presumption is derived from this process at any point.

What’s your perspective on Alan Parsons’ contributions to the sessions?

Mr. Parsons has an unusual approach to studio work. However, I am in no doubt his peculiar process is the thing which has set him apart from all other engineers to date and what has made him the great success he is today. Unfortunately, I seem to have forgotten what it is.

How did working at EastWest Studios influence your output?

While at EastWest Studios, I did a lot of coloring. I completed at least six large books of clown faces and ice cream. I like ice cream.

So, what’s your take on how the band has gelled since it debuted in 2012?

Mr. Wilson has created a very secure environment for us all to work and play in. He has also developed a machine which he refers to as “The Sanitizer.” It is compulsory for each member of the band to spend 15 minutes in it each day for the well-being of the group. Once, Adam Holzman hid and pretended he'd been in, but later we caught him listening to country music, which made Mr. Wilson very angry. I don't like it when he gets angry. Have I said too much?

Photo Credits:

Steven Wilson by Naki

Theo Travis by Joe Del Tufo