Donate to Innerviews

Since 1994, Innerviews has provided uncompromising, in-depth interviews with musicians across every genre imaginable. And it does that with no trackers, cookies, clickbait, or advertising.

Your donations are welcome to help continue its mission of highlighting incredible music and artists, without any commercial considerations.

Your contributions will be instantly transformed into stories and videos, and cover hosting and web management costs. Importantly, your dollars will help ensure Innerviews remains absolutely free to all visitors, independent of their ability to financially support it.

Please consider making a donation today by using the PayPal QR code below.

Victor Wooten

If People Were More Like Music...

by Anil Prasad

Copyright © 1996 Anil Prasad.

Think about the word "music" for a second. Really think about it. It possesses no borders or limits. It's comprised of infinite colors, ideas and viewpoints. So, what if people were more like music? It's a question bassist Victor Wooten has been answering throughout his career.

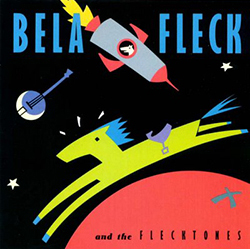

He's known for his role as a founding member of Béla Fleck & The Flecktones. The famous banjo-driven trio takes an everything-and-the-kitchen-sink approach by weaving together a multitude of influences into its addictive instrumental pieces. Whether it's working with jazz, bluegrass, Celtic, rock, funk or rap elements, the band's goal has always been bridging the gap between genres, musicians and audiences.

The Flecktones' open-ended mindset also propels Wooten's recently-released solo album A Show of Hands. Comprised solely of his jaw-dropping fretwork and vocals, the disc makes a strong case for the bass as a lead instrument. In fact, the album goes so far beyond conventional ideas about the instrument that listeners often forget they're hearing virtually nothing but bass.

Wooten uses one of the most unique techniques ever devised in the electric bass guitar's short history. He visualizes his thumb as a pick and through a series of rapid-fire up-and-down strokes, uses it to punch out amazingly intricate and eloquent sounds. The method enables him to perform solo on his bass with impressive flexibility, subtlety, warmth, and lyricism.

Whether it's classical music, jazz standards, funk workouts or quiet, folksy pieces, Wooten is able to deliver on his instrument. That's evident throughout A Show of Hands' 10 tracks. But he realizes no matter how diverse and expansive his music sounds, there are listeners who will refuse to see past the bass guitar's traditional role as a supporting instrument. He asks that those people listen instead.

This interview delves deep into Wooten's muse. It explores the Nashville resident's philosophy of "peace above all" and how it applies to his music, life and family. We also journey through the art of "lead bass" and his evolution as a player and composer.

I understand you just finished working on a soundtrack project a couple of days ago.

Yeah, The Flecktones—we were working on some music for this movie. It's a new Demi Moore movie called Striptease. We were in New York for two days recording some more music for it. They had to re-shoot the ending so they had to redo the music for the ending of the movie.

Is working on film music an enjoyable experience for you?

It's fun—a great experience. It's really not even our own Flecktones music. It's Howard Shore who wrote the soundtrack. We're just doing some of his music. We're mixed in with a bunch of other people—a whole orchestra, Chuck Loeb on guitar and Gordon Gottlieb playing percussion. The Flecktones with Howard Levy are part of the band. But for the most part we're playing along with the whole orchestra.

A Show of Hands was just released, but it's actually been in the can for several years.

Yeah, I recorded the bass parts about two years ago at least—maybe three years. Let me think. Was it June of '94 or something...? I recorded it quite awhile ago and played it for some people. And since then, I slowly added vocals to different songs. Some of 'em already had it, but certain songs—even up to the last minute—I was adding just little bits and pieces here and there to make it totally the way I wanted it. I had already mastered the whole album when I decided to put the vocals on the first song, "You Can't Hold No Groove."

So, the original version of the album had no vocals at all?

There were none at all. I had mastered the whole thing and was ready to send it over to Compass and I thought "Wait a minute, man... this would be neat if this happened." So, it was like a copy of Larry Graham-style vocals that I put on there—myself and Will Lee.

A couple of years ago, you told me you had finished the album and couldn't get label interest from anyone.

Yeah. A lot of people are kinda scared of it, you know. I mean I got some good response and some major labels wanted to put it out. Some labels said "Man, this is great. Let's do it." Then they would turn around for whatever reason and say "Well, no, I don't know if we should do this" and then vice-versa. Some labels at first said "No" and then turned around and said "Yeah, we wanna do it." But I decided to either put it out myself or put it on a small label. And I ended up sticking to that. Being with The Flecktones, I'm in a great position because it's sorta like I have a major label affiliation being with them and it's sort of like having a major label deal because as much as I get to play and as much as I get showcased with The Flecktones and with those recordings, I get the benefits of what Warner Brothers has to offer through The Flecktones. But sometimes the major labels see things differently than I see them. My main goal is not just to have a record in everyone's home or something like that, but it's maybe to touch a few people... or as many people as possible—not just to put a record out for the sake of having it out there. I wanted to do a record that was totally me. And I had the feeling that that wouldn't be major-label-type of material—it'd be a smaller type of thing or even just puttin' it out myself. But the people that got it would totally be touched by it—affected by it. And, hopefully, it would make them think and just appreciate life better.

Last summer, we discussed the album again and you seemed really frustrated. You said "You know, I'm just glad I got the album done. I did it for me. If no-one ever hears it but me, that's fine." You've obviously had a change of heart.

Well... uh, yeah. [pauses] That's not out of frustration, though. That's just the way I did it. I mean, you can live a whole lifetime trying to please everyone else and I think that's what most other people do—they make records that are gonna have the mass appeal, but a lot of times you end up forsaking your own joy and things that you like to do because you're pleasing the record company or whatever. But my goal was to make a record that I was pleased with—totally. I kinda did it totally for myself in hopes that other people would enjoy it also. But I really didn't go into this record thinking well, you know, "What are people going to like?" That wasn't my main goal. My main goal was to get a record together that I just totally felt good about. And I think live... in performing, you know, if you totally put yourself into it and be honest and true with what you're doing—which is what I did with this record—I think that will carry. And the people that do get it—get it in a way that people don't get things if you just do a project with ulterior motives, maybe just to make money or just to do something that's popular at the moment... [pauses] You know, people enjoy that, too, but that's kind of superficial and it doesn't really last. I don't know really how to explain it. I just wanted something that was more real. And since I don't know what the whole world likes—I only know what I like—I decided to do a record that I liked.

How did A Show of Hands end up on Compass Records?

Compass is run by friends of mine and they're musicians. And I remember when they started the label, they really wanted to do something that was really about music—a label that was about the music and about the musicians. They're really into helping the musicians be able to make money and make records the way they want them made. And them being musicians themselves, they're really good at that 'cause they know what musicians need. But when I first made this recording, I just kind of gave it to a bunch of friends of mine. I didn't send it to a lot of labels at first. I gave it to a bunch of musicians just to see what kind of buzz it was gonna get that way. At the time my main goal wasn't like "Okay, what labels are gonna be interested in this?" I got it to different musicians like Branford Marsalis and Chick Corea and friends of mine that way and I figured, "Wow, if they dug it then it would make its way to the record labels."

And how did those cats react?

Well, they loved it. Because GRP almost put it out—it was either gonna be GRP or Chick Corea's Stretch label. They were totally set and, then, for whatever reason they changed their minds about it. But they really loved it. I sent one to Marcus Miller and he gave me a phone call and he just totally loved it too. And Stanley Clarke, he really liked it. He actually thought that it was out when I gave it to him. When I talked to him again he was just sayin' "Man, if there's anything I can do to help this thing..." He was just totally into it.

That must have been pretty gratifying. I know Clarke is a hero of yours.

Oh man! So gratifying to have these guys that I grew up listening to, you know, digging what I'm doing—and even Stanley saying that he can hear himself in my playing, you know. That's a major thrill. But yeah, I was getting good response through these musicians and even they were turning it on to their record labels and things like that. So, you know, I was getting to talk to some of these people. But the overall response was "Yeah, it's great, but I don't know what we could do with it." That's the major label mentality. I don't know how I mean it. Well, I do know how I mean it, but I don't know how to say it without making people upset.

Go ahead and upset them.

[laughs] With a lot of these labels, the goal is not to put out good music. It's to put out music that will sell. Does that make any sense?

That makes total sense.

Yeah.

I'm still amazed at the fact that there was a time—in the mid- to late-'70s—when some bass-oriented albums would actually sell hundreds of thousands of copies.

Right, right. Exactly. But I do think that that era is coming back. I really do. Yeah, I think it's comin' back with certain groups. There's a lot of groups that are coming around nowadays—even in the grunge scene and alternative bands. That's one thing that I like. Bands like... even Hootie and the Blowfish. You know they have their own sound and they're a band. They're not popular because there's this one guy who dances great in the video or... you know, these guys look like models or whatever. You know, part of their whole appeal is just their sound. And there's a lot of alternative rock bands that are coming around that are like that. Like Blues Traveler, you know, they even won a Grammy this year and the lead singer's this large guy that plays harmonica. But that's great! You know, there's the Dave Matthews Band, even bands like Green Day, you know, that are just these crazy bands, but people are liking them, you know. And it's not even whether I like their music or not. It's not so important, but the people that dig 'em are digging 'em because of their music. And they're bands. They have a sound. It's not just, you know, computer generated and molded to fit the mass appeal. They're just doing what they do and people are catching on to it. So it seems like that that era could be coming back. I hope so anyway.

Describe how A Show of Hands evolved from a solo bass album into one with vocals.

Well, I have for many, many years wanted to make a solo bass record where I did no overdubs and had no other instruments, but I wanted to make it in a way that someone could sit down and listen to it for 30 to 40 minutes—you know, even myself. Because even myself, just to sit down and listen to the same tones and things like that for 30 minutes or whatever, I've had enough. If I go to a concert, even if the band is amazing, if it's the same thing for awhile, I've had enough after about a half hour. So I was trying to think of ways to make this record with just bass, but make it interesting so that someone could enjoy it and not have their ears get tired for the duration of the recording. So, I chose songs that I had been working on and I just did songs using timbres and tones and EQ and different things to make each one slightly different. And then I started thinking "Wow!" because I had come up with this version of "Words of Wisdom." I had come up with this music and I thought "Man, this would sound so cool with people just talkin' over the top of it." And then I thought "Well, you know, it would still be solo bass and this would actually make the recording better." And that's eventually what I wanted, a good recording, not just something that's solo bass. It's got to be good first. So, I started adding vocals here and there—and then vocals in between songs and the idea just started to develop and I just loved it. And I started adding more and more—adding some comical things. And it turned into a record that I enjoyed more than my original idea.

The album goes way past the conventional idea of a "bass player's album." But that's not going to stop the media from labeling it that way. Does that bother you—the fact that it will be regarded as a "great bass album" instead of "great music?"

No, because you can't decide what people are going to think about what you do. And a lot of people drive themselves crazy because they don't get the response they want from people. But again, you can't decide people's responses. I hope that people call it whatever it is they truly want to. I just hope people give it an honest look, and come up with an honest opinion. Don't call it a solo bass album just because the only instrument is bass. You know, just be honest. If you like the music, I'm happy. If you don't, I'm happy still. I'm not real concerned as to what people call it or think about it as, long as they're honest with themselves. And what I mean about that is, you see, a lot of people fall into the fads. They'll like a group not because they like it, but because everyone else does. And with this record, it's so different. It's not real easy to jump on the bandwagon to find out what this record is because there's really no bandwagon. It's really an individual record. You have to like it by yourself or not. And I just want people to look at it that way. I want people to decide for themselves. And I don't even so much think people have to decide whether they like it or not. Just listen to it, you know? [laughs] Enjoy it and see how it makes you feel.

Despite the labeling and tags the media will slap on A Show of Hands, I think its greatest strength is that average listeners can completely forget that they're listening to mostly bass—and the vocals go a long way to helping that.

Well, I think that's great because first it's about music. It should be anyway. And the instrument is just a vehicle to express the feeling inside of you. You try to get it out through the music. And it really shouldn't matter what instrument a person plays as long as he's making the music that he wants to make out of it. And so that was my goal—to be able to make music. I hope people can hear the record as music and not get caught on the fact that "Wow that's just a bass! I like it or I don't like it because it's just bass." And that's the way a lot of record companies look at it. They see that first rather than the music first and it should be about music.

You've got a piece called "Classical Thump" on the album that totally contradicts most people's expectation of what can be expressed via bass guitar.

Right. [laughs]

Tell me how you go about structuring a piece that intricate and complex for the bass.

Well, that's a really good question. I'd have to figure it out—it's something I started doing really young. I'm the youngest of five brothers and all my brothers play different instruments. And I used to always take the things that they did on their instruments and learn how to do them on the bass whether it was an actual melodic line, whether it was a drum rhythm or whether it was a technique—I would apply it to the bass. And so I would hear my brothers play these type of things and also, I played cello in the orchestra. And I would hear these type of things or I'd hear Flamenco guitarists doing these techniques and I just figured out a way to do them on the bass. I used to also learn drum solos, but I would learn them on the bass. And it would make me figure out different techniques and I learned a lot of different rhythms that were different for the bass. So, if I heard a whole orchestra do something, I tried to recreate that whole sound on the bass. You know... I don't really know how I go about doing it. Umm... but to me, it's more of a feeling. Music makes us feel a certain way—a lot of the times whether we realize it or not. And so when I'm working out a song, I try to recreate that same feeling. The technique or whatever is secondary.

Do you enjoy the process? Many musicians would start banging their heads against the wall trying to put together a piece that difficult for four strings.

[laughs] Right. Sometimes you can get there because you're just not producing what you want. You have it inside, but it's just not coming through the instrument. But a lot of times I'll just let it go for awhile and come back to it later. But the process is fun though. I mean, it was really enjoyable because you're seeing the birth of this new idea come about and that's an amazing thing.

You've started to play a lot of your solo material live.

Yeah, most of this month The Flecktones have been off. Béla's been home finishing up a live recording that we're gonna come out with in a few months. So, I took the time to grab a drummer—a friend of mine named J.D. Blair, and we've been out just doing bass and drums. And, man, it's been fun—great turnout and some great responses. Yeah, we've just been having a great time.

Do you plan on taking this on the road in a major way?

Well, we're planning on doing more. We did about 15 or 16 dates. The main thing that's been keeping me so busy is the fact that The Flecktones are so busy. I have to work during The Flecktones' off-time which ends up leaving me with no off-time. And it's been really, really tough that way, but we definitely plan on going out again and doin' it some more.

How do your tunes translate live in the duo format?

They actually translate very well. They translate better it seems, because with the drums, you really latch on to the rhythm and the groove of the whole thing much, much easier. You see, when I'm playing these songs, I'm trying to add in the drum part when I'm doin' it solo. I'm trying to make sure you hear the drum part along with the bass line—you know, some semblance of the chords and a melody. And with a drummer I don't have to work as hard to pull that off. And so I can concentrate more on some of the other areas even though I'm pretty much playing the same parts. But a listener understands it much, much more.

"Me and My Bass Guitar" must be devastating with drums.

Oh, yeah. It's powerful... [laughs] It's powerful.

I understand you're using some sequences too.

What I'm doing sequence-wise is I have all the vocals in a sampler and I'm triggering them. I'm triggering the sampler with a foot pedal. And I also have the drummer triggering some of them. So, for example, when I do the lyrics for "Me and My Bass Guitar," when I get to the chorus, you hear the whole chorus, rather than just, maybe, myself saying "me and my bass guitar." You hear the whole thing and I also have Martin Luther King and Malcolm X and the children singing in "More Love" and all that stuff from the record in the sampler.

Innerviews has spoken to a wide variety of bassists over the years and the consensus seems to be that club owners are simply not interested in bass-oriented shows. Have you faced any problems getting gigs?

Well, I'd say no as far as this last tour went, but I didn't do any of the booking. I turned over to the same guys who do The Flecktones and they booked it. But when I first moved to Nashville, I got a job in a health food restaurant called "The Slice of Life" playing solo bass in 1989 and 1990. And the way I convinced them, 'cause they wanted me to come in and audition... they asked me what instrument I played, and I told 'em I play guitar. So that got me to the audition. And once they heard it, they understood it. And they loved it. It turned into a great thing. But yeah, I can see how a lot of venues would have trouble with the fact that they're gonna give away one of their nights in this club for a bass player to come in and do a show. I can see how they'd have to think twice about that.

Why do you think that is?

Well, most people still don't see the bass as a lead instrument or as an instrument that anyone's going to listen to for longer than a couple minutes solo in a song. So I can see that as being why they don't think they're gonna make money with that. Where a guitar player, you know, we're used to seeing him out front. And we're used to a lot of frontmen guitarists like Yngwie Malmsteen or Steve Vai, and a lot of jazz guys like George Benson that play guitar. We're used to that being out front, but the bass we're still not used to.

The perpetual question people pose about boundary-breaking bassists like yourself and Michael Manring is "are they really playing bass?" Many can't seem to cope with bass outside of a supporting role.

Well, see, it's not the instrument. All Michael Manring and myself are doing is just trying to make music. When we're playing solo maybe we aren't playing bass. We're playing music, basically, is what it comes down to. We're going past being a bass player and are being musicians. And that's the goal. You know, it's like a guitar player sits down and plays a solo piece. You're gonna hear the bass lines, the chords and a melody more than likely. But you still recognize it as a guitar. Whereas with the bass, we're so used to just hearing the bass line by itself that when someone like Michael or myself or Stu Hamm plays a full composition, sometimes we get drawn away from the fact that the bass line is actually still there most of the time. And because we hear so much more, we think that we have forgotten our duty or whatever. But, actually, it's not that case. We have gone past that and realized that the instrument is there to make music. And that's what we're doing with it—making music.

The bass instrument's purpose is not just to play one or two notes to support everyone. It's to make music. And basically, that's however you wanna do it. Now, yes, the bass usually performs a certain role and that's that support role and holding up the bottom and defining the core, but that's like saying all tall people have to play basketball. A tall person should do whatever makes him happy when it gets down to it. You need to get past all the stereotypes, and those type of things. I understand the people that have problems with what Michael Manring or I do, but I would also say that a lot of the people who are saying that are the people who can't do what Michael Manring does. They don't feel like putting in the time that Michael Manring has put in. And they'd rather put in the time to complain about him or ridicule him rather than just listening to the music or seeing whether Michael's getting enjoyment out of what he's doing. Cause that's the main goal, anyway.

What do you think of Manring's music?

Michael's great. He's incredible. I love the way he can do all that tapping stuff on a fretless. And Michael's himself. He's not being like anyone else. He doesn't play like anyone else. He plays exactly the way he plays. And I love anyone who does that whether I like their music or not. That doesn't matter. As long as they're doing what they love to do and they're just being themselves, that's great.

Some believe the bass is one of the most misunderstood instruments out there. As you said, it's surrounded by stereotyping. Why do you think people are so closed-minded?

Because people get stuck in patterns.

But they don't for other instruments.

Well, that's because the other instruments have evolved over the years. I mean, the bass is getting there. It's definitely getting there, but the same with guitar. It had its role. Same with the banjo. The banjo was in jazz music before the guitar was. But for some reason, the banjo hasn't made the transition into jazz like the guitar has. You know, for whatever reason. But the electric bass is still such a new instrument and I think people are still just stuck in the traditional roles that it's played. People are slowly waking up like all of us. We're slowly waking up to the possibilities of the bass. People wouldn't think twice about hearing a solo bass vocalist—that's no big deal. But a solo bass guitar is another story for whatever reason. People just need to kinda open up their minds and listen to the music. Don't get caught up on the instrument. The instrument is secondary.

In many ways, that's been the driving force behind The Flecktones, hasn't it? All of you are doing unconventional things on your instruments—or even creating entirely new instruments in Future Man's case.

Right, right. And it's been kinda neat. Because of that fact, I didn't think the band was gonna be successful. I figured we'd be successful underground—meaning musicians would dig it and understand the music. But we play all this strange music and the public's been gettin' into it—children and grandparents. And I think a lot of it has to do with the fact that we're just doing what we do. We're honest with what we do. We're playing music that's totally us. We're not trying to conform to anything or make records for radio. And I think that honesty gets through to people. I really think it does. People can pick up on it in ways that maybe they don't even understand, but they end up liking it.

How did The Flecktones first come together?

Well, starting from the very beginning of me finding out about Béla, I was working in Virginia at a theme park called Busch Gardens and I used to play a friend of mine's banjo. I was playing in a country band at this amusement park. And I used to play my friend's banjo during the breaks. Because the banjo has this altered tuning, it's different from the bass. When I would play my regular bass patterns, they'd sound quite different on a banjo. And I would do all my thumbing patterns and stuff. My friend kept saying "Man, that sounds like Béla Fleck!" And I was, like, "Who is Béla Fleck that plays banjo like this?" I wasn't used to hearing any weird stuff like this on banjo. And so he brought in some New Grass Revival records and I was totally hooked into that music. I loved it. And later on, with the same friend of mine, John, we took a trip to Nashville to visit. And I was staying with my friend Kurt Storey, who actually ended up engineering my record. I was staying with him and he knew Béla. So we called him up on the telephone. And Kurt had told Béla about my brothers and me. So Béla said "Well, hey man, just play something over the phone." So I just played some stuff over the phone. And he liked it. He said it sounded a lot like a bass banjo because I was using a lot of similar techniques that he used. And that led to Béla and I getting together and having a jam session at his house—just the two of us. And we just hit it off musically and personally.

A few months or about a year after that he called me about doing this television show called the Lonesome Pine Special. They were gonna produce a one-hour show on Béla and he could do whatever he wanted. And he was interested in jazz music and stuff. He had been writing a bunch of weird music. And he asked if I would play bass for this show 'cause he wanted to end the show with a band playing some of his music. And I said "sure." And he had told me that he knew this harmonica player, this guy who played harmonica and keyboards that he had met up in Winnipeg at the Winnipeg Folk Festival. And he wanted to get him and he wanted to get me and he needed a drummer. And so I told him about my brother. And I was telling him about these experiments my brother was doing with this electronic stuff. So Béla kept asking me questions that I couldn't answer. [laughs] Eventually, I said "Look, let's just call him up." And they ended up talking on the phone for hours—just talkin' you know. And after just talking, Béla said "Man, this is the guy for the show." He hadn't heard him play or seen this instrument or anything. But just talking, he said "Man, this is the guy." So we got together to do that one show and that was the birth of The Flecktones.

During the last half of "Sinister Minister," you've been known to switch instruments with Fleck and go nuts on the banjo.

Yeah, it's lots of fun. We have played that song so many times that we were just trying to figure out how to make it interesting for ourselves and we decided to do that. Because so many people have noticed that our techniques are very similar. It's always fun to hop on another instrument anyway. But the audience also gets such a kick out of it. It's just a lot of fun doing that. It's not something we do every night, but we have been doing it quite a bit.

What's it like for you to play banjo?

The banjo is fun to play. It's tougher for me because the string spacing is much closer together and you have that fifth string—that odd fifth string that's just stuck up there somewhere. [laughs] It takes awhile to get used to it. But there's some neat things that the banjo has. It's so percussive and it's a great funk instrument because of its percussive nature. The funk guys just haven't realized it yet. [laughs] I mean, it's strings on a drum head. You know, that's great! And all the notes are short. It's great for some real funky music. And because the pitches are high, you can play chords and just about any notes and they sound great as a chord. It's just a really great instrument.

You've pretty much brought the "up and down thumb stroke" style of bass-playing to the forefront.

I'm definitely not the first one to do it. I have helped bring it to the attention of a lot of people. But my oldest brother Regi showed me that maybe when I was eight or nine years old or something. And guitarists have done it for ages. Wes Montgomery played that way. And I think of it just like using a pick except I use my thumb. There haven't been a lot of bass players that I know about that have done it, but I do know people have done it. I don't know whether Larry Graham ever did it, but that's why I started doing it—to help me get the sound that Larry Graham had. And there's a guy named Abe Laboriel who's done it for years also. Just about every technique that I do, Abe does also. He just uses them in his own way. I saw a video of his and I said "Man, he's doin' everything I'm doin'." But we just use it in our own ways. A lot of classical and flamenco guitarists use the technique also.

Almost anyone who brings a technique to the forefront and gets as much attention as you have gets imitated almost immediately. Legions of copycats suddenly appear—what happened with Jaco's sound is a good example of that. But that hasn't happened in your case.

People are startin' to do it more. But one thing about this technique is it really takes some work to get used to because it's totally different from what us bass players are used to doin'. Slowly but surely I have been hearing people come out with things that I can really tell that I have influenced. And I think it's great.

Can you name anyone in particular?

I'd probably even hate to say... [long pause] but there are definitely players out there. I just don't wanna come off saying "Oh yeah, this guy got this from me." It's just that I can hear influences. I know that I've influenced players—even some major players and friends of mine. But it goes both ways. We all influence each other. That's evolution.

You've been the subject of a great deal of adulation. Titles like "the greatest player to ever pick up the electric bass" and "the most evolved player in history" have been attached to your name. How do you deal with that?

It's a very radical thing for people to say and have happen to me. I'm still not used to that kind of stuff because I don't see myself that way at all—especially with guys like Stanley Clarke, Marcus Miller and Larry Graham. These guys that I learned from are still around playin'. So they'll always be above me the way I look at it. To hear people say that about me makes me wanna start talking about these other guys. But I just say "thank you" and realize that people are free to decide what they wanna decide. They're free to look at you however they want. And it shouldn't be my desire to change that. Whatever people wanna see is up to them. So I usually just say "thank you" and just try to let them hopefully see themselves in the same way that they see me.

There's people puttin' me up on pedestals a lot of the time and I used to try to take myself off that pedestal. But I've finally learned that, wow, if people can have those high sights... I mean, if they can see something that high, that must mean they have the potential to gain that. They can be that high. I try to show them how they can be up that high also. It's good to be able to see high goals and see, "Wow, this person is way up there," because that lets you know where the possibilities are. But I just try to let people know that they can do everything that I do and definitely even more. So I approach it that way now. I go ahead and let them say those great things about me, but I try to bring it to their attention that they have every ability to do the same.

During your raps with The Flecktones and throughout your solo album, you often talk about peace. What does peace mean to you?

Peace and love and all that stuff is what's necessary for anything else to happen. I need that freedom and that peace inside me to be able to take the bass to the level that I wanna take it to. So it all relates back to music, but it's actually at the forefront of the music. That has to be there first. A good example is when a lot of slaves were brought to this country, their instruments were taken away from them, and they had to express themselves through different means. I just strive for the freedom for people to be able to express themselves the way they choose—whether that's music or whether that's sweeping a street or whatever. It's about allowing people to be who they wanna be.

So, peace equals freedom?

Peace definitely equals freedom. Peace, to me, I guess, if I had to describe it, would be the freedom to express who you are. That's one way of saying it. That's a good explanation. I'd have to think a little to see if that covers all of it, but that's definitely a good one—the freedom for all things to be who they are.

What do people have to have in place before they can embrace that philosophy?

They have to stop worrying about what other people think they should be. Most of us define ourselves by what others think of us rather than what you think of yourself or who you wanna be. In other words, we wear these clothes because they're in fashion—that's what everyone else says we should wear. I wear my hair this way because everyone else thinks it looks good. You know, if I wore my hair or the clothes I wanted to wear and I went outside and everyone laughed at me, I'd probably come back in and change into something that, really, is maybe not me, but suits everyone else. So I think that everyone should just really go inside of themselves and find out who they are and strive to be that. It really doesn't matter what the other person thinks. If you are truly who you are, the other person will grow to like that more than likely.

During one of the spoken word parts between tunes on A Show of Hands, you talk about the Sesame Street bit that goes "One of these things is not like the other, one of these things just doesn't belong."

It is, but I didn't use that name [Sesame Street], but I think most people know that that's what it is, yeah.

You basically use that to assert that everything belongs—everything is somehow part of God's plan, including racism and injustice.

Well, I think it's all about acceptance. And usually every problem arises because of a lack of acceptance or rather we want other people to accept things the way that we accept them. Basically we want all things to be the way we want them to be rather than accepting things as they are. And that song "One of these things is not like the other, one of these things just doesn't belong" all of a sudden was saying something doesn't belong because it's not like everything else. And I can remember being a young kid—and moreso my brothers being the only black kids in a class and part of your school is watchin' TV in elementary school and they used to bring videos in from Sesame Street and things like that. And these are things that you're being shown—"One of these things is not like the other, one of these things just doesn't belong." And so you look around see which one of these people in this classroom is not like the other. And all of a sudden, they're teaching you in class that if you're not like the other, you don't belong. So the main thing I'm trying to say there is that everything belongs. We just have to learn to understand it. We have to learn to understand the role that everything plays. And then it helps you accept things and then everything is easier dealt with—when you realize that everything does have a place. I guess you just have to figure out what your place is within that.

I know racial harmony is something that's on your mind a lot.

Yeah, because it's just so sad that after all these years racism is still a big part of this country and of so many countries. You know, we're almost in the year 2000 and people are still looking at color.

Can you describe a situation in which you've encountered outright racism and how you dealt with it?

Well, I could bring up so many incidents, and there are some that are blatantly obvious. You know—where someone calls you a name or someone sees an interracial couple or something like that. There are so many incidents, but what even gets me more are the incidents that people don't catch because it's just a part of society. And I'll give you a good example. Two days ago, we had just arrived in Atlanta to play a show. And we just pulled up to our hotel room and we got out of our vehicle and there was a guy coming out of his room—a white man coming out of his room in a shirt and tie and nice slacks, briefcase and everything—you know, a businessman or whatever. And he looks over at us and he says to me "What part of the parking lot are you guys working on today?" And I looked behind me 'cause I thought he was talking to someone else and I said "Excuse me?" And he said, "I was just wondering what part of the parking lot you were gonna be working on today." And I said, "Well, none of it." There were some people working on the parking lot and he just assumed it was us 'cause I had my baseball cap and warm-ups on. And I said, "No, sir, I'm a guest just like you." And I showed him my key. And then he just got in his car and drove off. There was no "Oh, I'm sorry. I mistook you for such and such," or "My fault," or whatever. He just got in his car and left and probably didn't think anything of it. And those are just the little ways racism still prevails. And it's not even racism so much as in black and white, it's just how we judge people by the cover—judging a book from its cover.

I'm looking at that issue as broader than just a black or white issue because blacks, we look at whites the same way and I'm just hoping that we can get into seeing people as people and not because you wear this or you wear that then you must be this type of person. I could've taken a few different approaches to it, but I was nice with the man. Because in situations like that, confronting it with the same attitude as the person that's giving you anger or whatever will just escalate the whole thing. It'll give that person reason to feel that way. But if you give that person no reason to feel that way, then it'll help defuse the whole situation. So that's the way I approach most of those situations. And some of 'em really try you—they really make you get angry sometimes. But for the most part, my main goal in that is to not give that person a reason—any reason—to feel that way towards me.

America has seen some real racial upheavals and divisive events in recent times. Obviously, the Rodney King and O.J. Simpson incidents come to mind.

Through it all, I still say that things are getting better. I mean, I'd have to say that. Racism and inequality have moved into different places and they may not be as visible, but they're still there. I still think that things are better. When I look at things like Rodney King and O.J. and all that kind of stuff, it makes me glad I'm here to be a part of it rather than somewhere else because I do think I try my best not to be that way—not to have those type of views—racist or to judge people by appearance or whatever. And I think we need many more people that way—rather than to run away from the problem and let it stay there. I'm glad that there are at least some people that are trying not to be a part of the problem. Basically, we need a lot of people like that here. So I'm glad that I'm here around it so that maybe I can help get rid of part of it or get rid of all of it.

Certainly an admirable attitude. But some people argue that it's simply human nature to push back when you're pushed around.

Yeah, most people say that it is human nature. That's what we're taught most of the time. But there are definitely other ways. There are definitely other ways.

It's all a matter of education.

Yeah, and once you're educated, you still have to be wise enough to use that education. Education is definitely a big part of it—being taught about the racism and everything. But you also have to be wise. Because there's not one solution to every problem. Each situation has to be handled in the appropriate way and that comes through wisdom. I don't think there's any education that can teach you everything about music or everything about life. You just have to kinda live. And you're gonna be faced with situations that you haven't been educated about and to me that's where wisdom comes in—which is very similar to education. But to me, wisdom is how you use your education.

Are you a spiritual person?

Yeah, a lot of people tell me that I am and I guess I would be termed a spiritual person. But to me, everything in this world is spiritual because the way I look at it, anything that exists physically had to exist spiritually first. So I don't see how anything couldn't be spiritual. But because I recognize it, you know, yes, I am considered a spiritual person. You know I love reading about it and I love talking about spiritual things. But I would consider myself more of a spiritual person rather than a religious person.

Do you subscribe to any particular religion?

No. No, I don't. I saw a bumper sticker once that said "God is too big for any one religion." And I tend to stick with that. I look at it like music. I don't consider myself a jazz musician because then what happens when I wanna play bluegrass one day? Am I not allowed?

The Flecktones have gone to a bunch of schools to do gigs and help open kids' minds to new musical and social ideas.

We have. We haven't done a lot, but we have. We played in elementary classrooms and colleges and things like that. For high schools too.

And even though you're there for the music, do you see the kids absorbing other messages too?

Kids definitely do. Kids are so great 'cause they really are innocent until they learn otherwise. I mean to see—especially when Howard [Levy] was in the band—two blacks and two whites and we're playing music with a banjo, a harmonica, bass and then this weird drum instrument, you know, basically, not following any rules, but coming out with something that's enjoyable. Kids totally understand it. No question about it because they see it for what it is, not what it's made up out of. They don't say "Wow, this guy's black so it's supposed to sound like this," or "This guy's Jewish and it's supposed to sound like this," or "This is a banjo and it's supposed to sound like that." Children don't think like that yet until they're taught that. So a lot of the time the kids understand the music much more than the adults because they don't try to analyze it or pigeonhole it or anything like that. But they also get the message which is different than what society teaches them a lot of times. And basically, the message is that you can make whatever is in your heart work. Whatever it is in your heart, you can make it work. And we're proof of that. By taking these instruments and taking them out of their characteristic traits, and still makin' it work—makin' it enjoyable.

Since Levy left in 1992, do you perceive any sort of imbalance in the group as a trio?

No. It just shifted us in another direction. I don't think it's an imbalance because we have covered for any lack, hopefully. It's like if you have a four-man team of any sort, and then one person leaves, the other three have to step up and it makes the other three have to grow. And that's what it did in this situation when Howard left the band.

Why did he leave?

He wasn't seeing his family enough because The Flecktones were touring so much. He has a wife and two kids. But also, Howard's not the kind of guy who likes to stay in one situation. And we had him for three years. He likes to play in all different types of situations. So, I think, that was probably just as big a part of it. He didn't have the freedom that he used to have. I think he had just grown a little tired of it.

You're married too, right?

Yeah, I've been married about a year and a half.

Any kids?

No kids yet.

Are kids part of the plan?

Definitely, yeah, within two years.

[Wooten asks his wife Holly "When are we gonna have kids?" She jokingly replies "Eight months and six weeks, hon'!"]

I didn't know! [laughs] Within two years we'll have some, I think. We're really looking forward to it. I just kinda wanna be done with the road some—at least as much as I'm doin' it now. I don't wanna be out that much when the children come...

[Holly replies "So you can watch the kids while I'm out on the road!"]

[laughs] Holly's an actress. She just finished a tour yesterday, actually—touring around with children's theater. So we're both out on the road quite a bit.

Nothing's ever the same after you have kids...

That's what they say. I know after my first nephew was born, it was a change for me. It was just amazing. One of my brothers having a baby... wow. So I can just imagine when it's us—when it's me. I'm looking forward to it.

Until you have kids, what would you say is the primary motivator in your life?

Music's definitely a big motivator in my life, but it's my life that motivates the music. You see, the music is like a language. And if I were gonna talk, I wouldn't talk to motivate myself. I'd have to be motivated to talk. And I approach music the same way. I need something to say—musically. And so that's why I try to get out and do so many other things with my life. So that when I come back to music, I have things to play or to talk about. It's like the blues, you know—just like the blues. When people have a hard day, they can sing the blues. If they have a hard life they can sing the blues. The best blues singers are the ones that are singin' about experience, 'cause they're puttin' their heart and soul into it. Well, I'm doin' the same thing except I'm singing a different type of blues. You know, most of my blues is happy. It wouldn't be considered the blues. But I let my life experience influence the music in the exact same way. So, for me, I'm about life first—being a great person, being the person I wanna be, being the best at that I can be and lettin' the music come out of that. [laughs]

How have The Flecktones grown as a band since it began seven years ago?

We became a full-time band in the beginning of 1990. Béla did his last gig with New Grass Revival on New Years Eve '89. But we had actually started playing some gigs back in, I guess, '89. And the Lonesome Pine Special, I guess, was '88. So yeah, it's been awhile. But we've all grown as musicians and people—I'll even say that. We've just been able to see the non-limitations of our instruments and of music even more. We've been able to travel the world so we've been able to learn more about world music and let that influence us. And to see how if people were more like music, then maybe we could all get along better. We go over to these countries and jam with people. We may not be able to talk to 'em, but we can sit down and jam with 'em and that's an amazing thing. But yeah, we've definitely grown as musicians. I think we've all gotten better on our instruments—learned more about our instruments—learned more about musical relationships. I could probably see it grow through my brother mostly because his instrument's always changing on a daily basis. And with each change it brings him new ideas. And for myself and for Béla the same way. We're just growing with the instrument. And then even with the loss of Howard, it really made us step up as far as playing music and even the musical technology. Béla's banjo is MIDI now and he has all these floor pedals and he's into a whole new world that he was never into in the bluegrass world. He'd just walk up to a microphone and play his banjo. Now, everything's miced and has MIDI pick-ups and all this kind of neat stuff.

Does The Flecktones format ever grow tired for you?

Yeah, in a sense. You know, we've done it so much. It's always fun for me to do other things. I don't know that I'll say that I get tired of it, but I do get to points... [pauses] It was fun when I went out and did my own tour—it was a whole lot of fun because it was a new experience. But also it's been almost a month since I've done a Flecktones show and we're gonna do one tomorrow so that'll be fun again.

It's all about balance.

Yeah, it's definitely about balance. It seems like whenever you do anything all the time, no matter how great it is, you're always happy to see a break from it, so that when you come back to it, it's great again.

Fleck never ceases to amaze me in the amount of space he gives to the other players in the band.

Yeah, yeah. Yeah. I mean, it is great to see that. But another thing, and hopefully this doesn't come off the wrong way... I give Béla total acknowledgment and credit for being that type of bandleader, but he also knows that he wouldn't have this band if he weren't that way... which is a big factor. My brother and I and even Howard are individualists. We are the type of people that basically we all see each other as equals. We had all done support roles and we knew that with this band, for it to be the best it could be, it would have to be an equal-type of situation. You know—not a one-person and a back-up band type of situation. When we all decided to do it full-time, I don't know if it was so much of a spoken thing, but we all respected each other that way. And Béla knows that if he were to hold me back or to hold Roy back, the band wouldn't be the same. The shows wouldn't be the same. The records wouldn't be the same. It would just be a totally different band. And he sees the strengths that each member brings to the family. And to hold that back would just weaken the whole family.

So, a double live CD is in the works? [Live Art, released fall 1996]

Right. It's not done yet. It's being mixed right now as we speak. It should be done any day. It'll be out this year. And I'm not quite sure of the exact date. Béla's at home right now struggling to get it done.

Why is he struggling?

Because there's so much music and the music spans a five-year period. He's trying to listen to it all, and decide what should be used, edit together, make sure it's right, and mix it.

"Edit together?"

Edit, yeah. Edit from night-to-night. And there may even be a few songs where we played one part great one night, but played the second part of the tune better the next night, so with the technology nowadays you can put those two nights together.

Some people object to live albums that are pieced together that way. The argument is it takes away from the integrity, honesty and vibe of the performance.

You see, the thing is, it's all about the outcome. It's about the music. It's like when I go see a movie, it doesn't matter to me what day they filmed the scene. It's about whether the music's good and enjoyable. That's the way I look at it. And to me, it's all about the outcome. I'm not so concerned about how someone does something, but I do understand what you're saying—which is why even in our studio recordings we try to play everything as live as possible.

Are there any overdubs on the live album?

There may be some. I haven't done any, but I do know there's some stuff on there with Paul McCandless playin' horn. And I know he was over at Béla's house the other day and he may have fixed some stuff—actually fixed a few notes. For the most part it is live. For the most part it is.

So, the live album spans various years and performances. I assume that means Levy will appear on some of the material.

Oh yeah, lots of people appear—Howard, Bruce Hornsby, Chick Corea, Branford Marsalis, Sam Bush, Jerry Douglas, Edgar Meyer, and Stuart Duncan... and probably some people I'm forgetting.

Will the "Sinister Minister" bass solo appear on it?

Yeah... well, the solo on there is edited to make it a little bit shorter. Because some nights the solo may be 15 minutes long. And we have to remember that in a live record, each song maybe shouldn't be 15 minutes long.

Shouldn't that be the whole point of a live album? To capture a realistic performance?

It's a long version though. [laughs] Howard's on it. It's a good version. I'm happy this album is happening. I haven't been around for all of it—the actual mixing and stuff—because I opted to go out and do some of my own things. And I also did a lot of clinics. And I've just been having to fit in so many other things that I haven't been around for the process. I'm just hopin' that it really captures the live element. And from what I've heard, it does capture a lot of it because people have always talked about how much better our live shows are than the records. And I just hope that it all captures that element.

I hear that a lot about The Flecktones too. Is that observation something that bothers you?

That doesn't bother me, no. The live shows should be better than the record.

But people have been known to say the shows are much better than the albums.

Yeah, and I'm glad. I'm very glad. I mean, I would love for people to think that our live shows are way better. Yeah, I mean, I am so happy to hear that—as long as they like the live recordings...

The criticism of The Flecktones albums is that the playing is much too restrained.

Uh huh. Yeah, I have heard people say that, but it almost wouldn't matter what kind of record that you do. However it's done, there's always gonna be some criticism. You can't please everyone. My goal is just to please myself. You can drive yourself crazy tryin' to please everybody. You just can't do it. But I've heard people say that the studio records are a little bit too contained or whatever.

Are The Flecktones ever under record company pressure to produce radio-friendly tunes?

No, no—not that I know about, anyway. We just get in the studio... I would think our records are probably, out of the instrumental bands, one of the more free bands—as far as gettin' to do the kind of music that we like to do. Compared to some of the other bands where it is more radio-geared music like Fourplay—that type of thing.

How much longer do you see The Flecktones continuing?

I see it going on until it's not the best thing for each of us anymore. And at no time have we put a time limit on The Flecktones. It's still a day-to-day thing. So to say how long it'll last, I really have no idea. Will it go longer? Yeah, definitely. But how long? I don't know. The main thing is that the three of us are enjoying ourselves.

It's been four years since the last Flecktones studio album.

The last one was Tales From the Acoustic Planet. [1995]

I thought that was a Béla Fleck solo album.

Well, that's how it was billed. But in a big sense it still kind of was The Flecktones 'cause the three of us were playing on it. It just had a lot of guests. It was just somethin' Béla had been wantin' to do. And since I was puttin' mine out, he decided to go ahead and do it. But the next record will definitely be the live Flecktones record. What happens after that, I don't know.

You mentioned The Flecktones going abroad and absorbing a lot of world music influences. Can you outline some of those?

Just last February or so, we did 40 days in Asia. We went to seven different countries. And in each country we would learn at least one song and we would perform the songs in our shows. And we'd maybe even get some guests from that country to join us on stage and play or sing the song. And it was just amazing. We actually came back and recorded some of that music. And I believe on the live record, there'll be a medley of some of those songs. And when we play, it always sneaks in there—some of these influences. We've actually written some songs that are totally copping that feel. We have one song that may be on the live record called "New South Africa" which is based off of a South African groove just from gettin' to visit the country and play with some of those musicians. It's just totally a different feel. It's like goin' to a country and hearin' a different language. They just have their own sound.

I'd like to go back to Stanley Clarke for a few minutes. You mentioned earlier that he heard a lot of himself on your record.

Yeah, he mentioned that in an article which really thrilled me. I think it was a Downbeat article. He had mentioned my name, so that was great.

How much of Clarke is in you?

Ah, man, I grew up listening to Stanley so much. I used to transcribe. Well, I use the word transcribe. Basically, I just learned it—not writing it down, but just learned it from his records. And ever since I was really young... and I got a chance to go see him play when I was between eight and 11. And I actually got to meet him after the show and hang out with him. And he was so nice to me. I asked him whether he had a broken string or something I could have. He actually got out of his chair and looked around and he couldn't find one. But he said "Here. Write me at this address and I'll send you something." So I wrote him a letter and he wrote me back—sent me autographs, pictures and a Return to Forever tour booklet and a bunch of stuff like that. And that really stuck with me. But my playing has probably come through Stanley's school of playing more than anyone else. Just through my tone, I always got a little brighter tone and did these fast lines—like Stanley. I even played an Alembic bass for a long while.

You shared a stage with Clarke when The Flecktones opened for his Rite of Strings show at the Montreal Jazz Festival in 1995. What was that like?

Ah man! That was amazing! That was the best. I mean to even look on the side of the stage and see him standing there.

So he was watching?

Oh yeah.

That was a spectacular gig. And perhaps the longest opening set in history. You guys were on for almost 90 minutes.

[laughs] Right, yeah. It was just great. I mean, if you can just imagine being a kid and you have some idols and all of a sudden, you get to meet them and actually share the stage with them—and things like that. You can just imagine the kind of feeling that can produce.

During one of your bass solos at that gig you quoted Clarke's "School Days" and "Lopsy Lu"—what was going through your head, knowing that he was watching?

[laughs] Yeah, it was just enjoyment. It was great. It was almost like completing the circle. This guy has shared with you and all of a sudden you get to give it back to him and say "thanks" in this tribute way. I can't really think of anything else I could do for him, more than that... to show his influence in what I do.

What do you think of his talents as an upright bassist?

Oh, he's unbelievable! A lot of people don't realize it. He is definitely one of my favorites. He's always been one of my favorite acoustic bass players. I've always loved his tone and, man, he's just great—his phrasing on acoustic. He's really great. A lot of people just think of him as an electric player, but man, he's an unbelievable acoustic player.

Did you hear the record from his acoustic tour?

Yeah. I enjoyed it actually. I enjoyed it much better live though. And I think I would've enjoyed it much more with a percussion player, but I did enjoy it. I was lucky enough to get a copy before it came out. I pretty much like anything Stanley's on and Al Di Meola and Jean Luc Ponty, they're both great—so it's good to hear them together.

What's coming up in terms of your solo career?

I need to start working on another solo record. I wanna get in and do another one. And I've been playin' with this guy named Tom Coster, who's a keyboard player. He used to play with Santana. He plays with Vital Information. Oh, he's great. He's an amazing guy. Oh, he's incredible! For the fusion stuff he's the top-of-the-line. He always has great players: Dennis Chambers, Michael Brecker and just great people. But man, he's an amazing musician. He's just a total veteran. He's been around for ages and his playing's phenomenal and he's just a wonderful person. But I've been playing some with him and this drummer out of Baltimore named Larry Bright. So we've been having such a fun time doing it. I could see that we may record something in the future. So I'm gonna do some more of the solo shows with the drummer and, hopefully, some rest and relaxation will be in the near future. [laughs]

So, your next solo record could be radically different from A Show of Hands?

Yeah, it won't be solo. There will be some solo stuff on it. But it also won't be the typical band playin' the music and the bass playin' the melody kind of record either. It'll definitely be still a different bass record, but it'll go in a different direction than the first one.

Any final thoughts before we wrap up?

I just suggest for musicians period to get out and have a fun life and let that influence the music—rather than feel that they have to make music their life. I feel that we should just make music part of our lives. And we get out and just try to be the best people we can be and maybe just try to teach people by example. If we want to change the world and be the type of person that you would want the rest of the world to be—let that idea influence your music. And just be truthful in your music and that will affect people more so than always trying to produce what you think the public's gonna want. If it's not true to you then I don't think that's a great reason to do it. But if you're truthful to your music, the truth that's in the music will reach people.

Thanks for your very thoughtful answers. It's been fun chatting.

It's great talkin' to you. Normally, I just get asked questions like "Well, when did you start. Who did you listen to? What kind of strings do you use?"

I've never understood the value of equipment questions.

I feel totally the same way. I definitely have things that I use. I say go for what makes you comfortable, just like clothing. Don't buy anything because someone else uses it. I mean, if that person's using it let that make you decide to try it out maybe. "Okay, Victor uses this amp, well, let me see what it sounds like," but don't buy it because I use it. But to me, it doesn't matter what instrument you play or what kind of strings you use—the music has to come from inside you. And you find the things that help you express that the best. The instrument you choose to play, the type of instrument, the strings, the amp, the equipment, all that is secondary. It just helps you express yourself better. There's no one piece of equipment that's going to make you the greatest or whatever. Michael Jordan, one of the greatest basketball players ever... it almost doesn't matter what kind of shoes he's wearing, he's still gonna be Michael. Yes, we all know he wears Air Jordans. But do we think he'd play worse if he wore Converse or something? The shoes don't make him Michael Jordan. It may make him more comfortable to be Michael Jordan, but the basketball skills come from him. It almost wouldn't matter what uniform he had on or what company made his shoes. He's a great basketball player because he's who he is. And music's the same way. You have to have the music inside of you first. The equipment's not going to produce the music.