Donate to Innerviews

Since 1994, Innerviews has provided uncompromising, in-depth interviews with musicians across every genre imaginable. And it does that with no trackers, cookies, clickbait, or advertising.

Your donations are welcome to help continue its mission of highlighting incredible music and artists, without any commercial considerations.

Your contributions will be instantly transformed into stories and videos, and cover hosting and web management costs. Importantly, your dollars will help ensure Innerviews remains absolutely free to all visitors, independent of their ability to financially support it.

Please consider making a donation today by using the PayPal QR code below.

Aaron Novik

Post-Genre Conceptions

by Anil Prasad

Copyright © 2020 Anil Prasad.

Photo: Dominick Mastrangelo

Photo: Dominick Mastrangelo

Unclassifiable and uncompromising are two words that describe composer, clarinetist and visual artist Aaron Novik’s output. As a musician, Novik has explored countless genres and influences across his 12 releases. He possesses an expert touch for making them intermingle, joyfully collide and recombine into something entirely unique. Novik’s recorded works are meticulously constructed and reveal a mindset determined to push the edges of form.

Novik just released a series of five EPs titled The Hotel of 13 Losses, Rotterdam, Berlin, O+O+, and No Signal. An overview compilation of material from the series is also available as The Fallow Curves of the Planospheres. Each EP delves into specific places and times in Novik’s life and epitomize his genre-less worldview as they traverse the realms of jazz, ambient, chamber music, noise, industrial, and folk. The recordings feature many notable avant and jazz musicians, including guitarists Matt Hollenberg and Ava Mendoza, bassist Lisa Mezzacappa, reedsman Kyle Bruckmann, cellist Crystal Pascucci, and drummers Tim Bulkley and Jamie Moore.

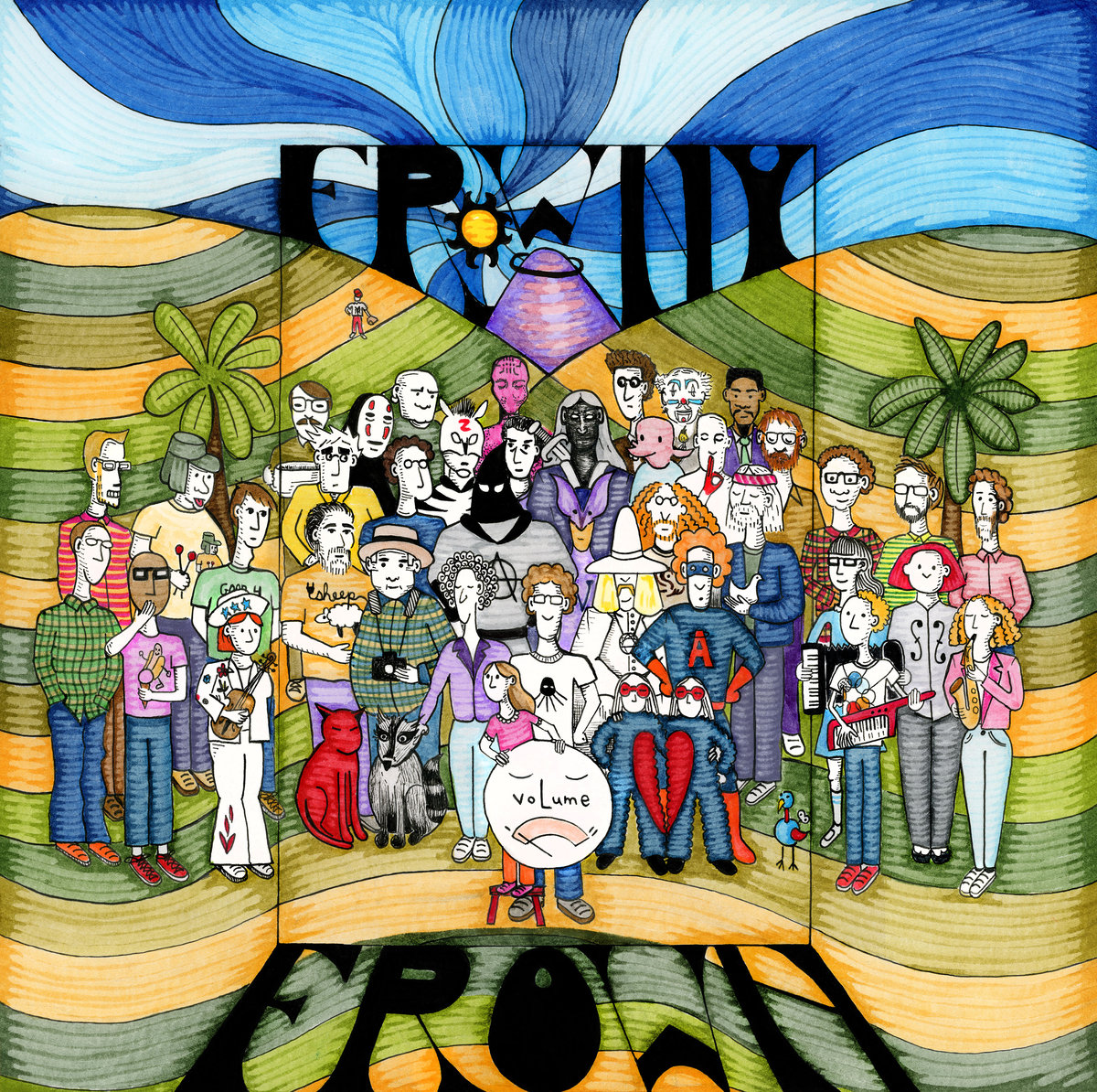

Frowny Frown, Novik’s 2018 release, and the first in a series of six albums that coincide with a six-part comic book series, is equally fascinating. It’s a complex, engaging construct that combines superimposed rhythms, Balkan and Indian elements, Brazilian chord progressions, and jazz harmony. It features track titles including “Hanks Piperaceous,” “Dante Counterstamp” and “Millicent Ruckdeschel” that have an intriguing provenance.

“It involves characters whose names were taken from spam emails,” said Novik. “Lyrics for later installments will also be culled from spam. The story involves magicians and scientists called thaumatists, artists, superheroes, gods, monsters, parallel universes, possession, drugs, ghost aliens, and of course politicians.”

Another key project Novik is responsible for is Secrets of Secrets, inspired by the writings of Rabbi Eleazar Rokeach, a 12th Century mystic also known as Rabbi Eleazar of Worms. The ambitious recording includes some highly-involved compositional approaches, including using Gematria, which identifies coded messages in sacred Jewish texts and assigns them numerical values that correspond to Hebrew letters. Musically, it’s in the orchestral art rock vein, but as with most of Novik’s work, infused with myriad global sounds. An impressive cast helps him realize his vision, including clarinetist Ben Goldberg, Real Vocal String Quartet, Mafia Brass, and guitarist Fred Frith.

Novik’s work as a visual artist accompanies many of his releases. His illustrations generally fall into the graphic narrative realm, and manage to retain a minimalist, textured and surreal feel, while communicating nuance and depth from their characters.

Innerviews examines Novik’s perspectives on the intersection between the aural and visual, and a wide variety of his projects in this conversation.

Describe the locales and musical frameworks your new EPs explore.

The first suite, The Hotel of 13 Losses, was written in San Francisco and utilizes field recordings made while traveling in France and Italy. I was traveling with a girlfriend of mine and the relationship was sort of dissolving, so those recordings seemed to fit with the theme of loss. One of the last clips is of her walking in heels down a flight of stairs away from me. Not super subtle.

The name of the suite is taken from a scene in a novel by Steve Erickson titled Our Ecstatic Days in which a gondola travels through a flooded LA into the Hotel of 13 Losses, where each room represents a different loss one can have in their life. The scene was so poetic and poignant it stuck with me for years and became the thematic glue to tie these pieces together.

Rotterdam, the second suite, was written in that city. After playing a few festivals with Fred Frith, I rented an Airbnb with a beautiful upright piano, and it inspired this simple, almost Satie-esque music. At this point I was traveling alone, having just split up with my girlfriend and fiancée. The music felt so peaceful to me as I was writing it, but listening back now, it sounds really melancholic and sad. Maybe it’s a little of both. I arranged the music for my working band Thorny Brocky, and recorded it a few years later.

After Rotterdam, I went to Berlin and wrote the Berlin suite there. I was also staying in an Airbnb with a piano, but that piano was balancing precariously on a bunch of books and I was told not to play it too hard. I took it as a sign and left it completely alone. It was the perfect opportunity to experiment with different sounds. I wanted to do something with no “notes” in it anyway. I just wanted organized sounds like bass and cello hitting their instruments, junk percussion, woodwinds with no mouthpieces—that type of thing. Berlin gives me this sense of industrial decay. I remember visiting an art space in a reappropriated building that was either a school or prison. I think reappropriating our musical instruments to sound like machines fits this sentiment well here.

The last two suites I wrote after I moved to New York. O+O+ was written in Brooklyn during my first winter in New York, and that winter was a doozy weather-wise. I was staying in a completely empty house a friend had just bought, so there was this Jack Nicholson The Shining vibe with being snowed in while living in this huge house all winter that I think translated to the crazy looping nature of this music.

This music was also inspired by a YouTube interview with Jason Marsalis I saw years ago, in which he criticizes musicians for never using swing, for only playing in odd meters, for taking ridiculously long solos, and it got me thinking about “What makes jazz ‘jazz?’” Does jazz have to swing? Does swing feel automatically make music jazz? I thought it would be fun to try and write music that used the swing feel but wasn’t jazz. I’ll admit now that it was harder than I thought. I think this suite definitely comes across as jazz, and that’s okay. I don’t think the music is a failure because the experiment was a failure. The experiment created some parameters that yielded music that is still new and different to me, just not in the way I thought it was going to be.

The final suite is called No Signal and it’s the most “New York” of all the music here. I was inspired by Kim Gordon’s book Girl in a Band and her romanticization of an older, grittier Manhattan. I made use of the not often heard “A clarinet” and wrote unison multiphonics. When played with both a “Bb clarinet” by Jeremiah Cymerman and an “A clarinet” by me, those multiphonics created crazy dissonances and overtones. To add to the insanity, I added two guitars that are also tuned a half-step apart, also utilizing harmonics and overtones to unique and surprising effect.

Talk about the unifying thread that connects the releases.

The music for all of these EPs is extremely varied, more than any other projects I’ve done, but there's a sense of experimentation and freedom that I think ties them all together. They all rely more on texture and a soundscape type of feeling than other works of mine. I’ve been doing a deep dive into the music of Brian Eno over the last decade and I think the big takeaway from his music is this sense of place you get. I think that exists with these suites as well. And they aren’t necessarily evocative of real places per se, even if they were written in different locations. The place could be in the imagination of the listener.

I want to add that I love the artwork that accompanies these EPs and the compilation. My wife Ariadna Garza made all these paintings last year for an art show she titled Habitantes, and I was using them as placeholders until she made some new art just for this project, but honestly I don’t think there could be better artwork to fit the moods of these suites. They are perfect and really evoke that sense of imaginary landscapes I was trying to convey, because she was going for a very similar concept in her work.

The O+O+ Ensemble: Michael Coleman, Aaron Novik, Anna Webber, Kasey Kundsen, Kurt Kotheimer, and Vijay Anderson | Photo: Dominick Mastrangelo

The O+O+ Ensemble: Michael Coleman, Aaron Novik, Anna Webber, Kasey Kundsen, Kurt Kotheimer, and Vijay Anderson | Photo: Dominick Mastrangelo

Tell me about the ideas that inform Frowny Frown.

Frowny Frown is turning into a sort of lifelong passion project at this point. I started it over 10 years ago, and I naively thought I could write six comics with six accompanying albums of music in 10 years, but I’m already past that deadline and I’ve only put out one part to date.

When I started this project around 2008, I was at a point at which I wanted to say more about the world we live in, in a way that I felt instrumental music couldn’t convey. I wanted to look at issues like religion, racism, sexism, inequality, technology and nature and thought a comic would be a fun way to do this. I was reading a ton of comics at the time and it seemed like a medium that is easy to connect with people through.

I started collecting spam email sender names, names that sounded crazy, unique and weird. They sparked my imagination, so I started creating characters with these names. At first I was just making these mini-comic flyers announcing gigs using weird stories I’d make up. I finally started to combine all these different storylines into a comic form and taught myself how to make comics.

I tried to make Frowny Frown almost three times before I came up with the comic I finally released. It was much harder than I thought it would be. It’s easily one of the hardest projects I’ve ever worked on. I’m only about a third of the way done at this point. I have a lot of respect for people in that field who make graphic novel after graphic novel. It’s so labor intensive it’s unbelievable.

How do the diverse, complex rhythmic and global musical influences serve the storylines of the album?

The comic and music interact in a number of ways. First, the album Frowny Frown is an actual storyline in the comic book. A character in the story—me—is working on an album named Frowny Frown, and ends up in a parallel universe, where a parallel version of himself is also working on an album called Frowny Frown, although this album sounds totally different.

This idea was inspired by Smile and Brian Wilson. I started feeling like there might be a parallel universe in which he actually finished Smile on schedule and I wondered what that would have sounded like. I don’t think it would have been the same as the version he finished recently. He had so many different versions of that music. The single version of “Heroes and Villains” is totally different from the album version. I love the idea that music doesn’t have to be just one way and that it can exist many different ways at the same time.

Second, the music to me has a sort of cartoon quality to it. I feel like it makes a good soundtrack for reading the comic—especially when I added Willie Winant on percussion like bass marimba and tympani, which also references Brian Wilson’s palette.

Third, I think there’s a sort of chaos to both the music and the comic with multiple storylines overlapping and mirroring the overlapping lines in the music. It was inspired by the Indian rhythms in konnakol. I created my own types of rhythms to create a polyrhythmic feel in the music.

What can we expect from the subsequent five albums in the Frowny Frown series?

Since technology is such a big part of the story, I thought it would be fun to release each issue and album on a different format, recreating a history of recording technology through all six releases. For instance, the first album came out on vinyl, and the music is made with all acoustic instruments to reflect what you might hear on a record at that time. The second release will reflect the ‘70s, and will be released on 8-track, and use electronic instruments popular at that time such as Fender Rhodes, electric guitar and electric bass, mixed with some acoustic sounds like congas and acoustic drum set. The third release will be ‘80s-inspired with drum machines, maybe some keytar, and will come out on cassette. The fourth will be on CD and so on. Maybe the format for the last release hasn’t been invented yet, but as of now, both the cloud and written score are the end goals—hyper-technology and a post-apocalypse return to basics. We’ll see. I still have a ways to go with this project and am currently in the middle of finishing up the second release, slated to come out in 2020.

Explore the conceptual basis of Secrets of Secrets.

Secrets of Secrets was my sole release for Tzadik records. I sent John Zorn a copy of my Samuel Suite record, which used Jewish music and Jewish scales to tell the story of my grandfather’s immigration to the United States. Zorn loved it and asked me to do a record for him. We went back and forth for a few years and ultimately he decided to pass. I was sad the project wasn’t going to happen, but immediately realized I could still make the record and just put it out myself. Of course when I was finished making it, I decided to send it to him anyway, and he contacted me right after he got it, telling me he loved it and he wanted to put it out. I was ecstatic of course. I was proud of myself for making a record that he liked so much that he went from a "no" to a "yes."

The project I proposed was to use the mystical treatise Secrets of Secrets written by Rabbi Eleazar of Worms in the 12th century as a launchpad for an intense orchestral metal record. Eleazar was a Kabbalist, who believed there were secrets hidden in the Bible that could be learned if one applied certain mystical techniques in studying it. These included substituting numbers for letters in a technique called Gematria and many other mathematical techniques. So, I thought it would be cool to use these types of techniques to put hidden messages in the music, and help to organize the music. Each song has hidden messages in it: The 77 names of god, the meaning of the divine chariot, the secrets of Genesis, and even an incantation to bring a golem to life.

As an atheist, I find religion in general to be weird and a little off-putting, but the worldviews from the time of Eleazar were so out there I found them to be completely fascinating. Being absorbed in those beliefs and mindsets for the year-and-a-half it took me to make that record felt insane after a while. The only other time I felt that removed from reality was when I binge read every single Philip K. Dick novel in a six-month period. You can’t help but have it influence your thought processes.

The Samuel Suite from 2008 was a highly-important project for you. Expand on how it serves as a tribute to your grandfather and captures his journey.

My grandfather was an important part of my life growing up. Even at a very young age, he never condescended to me, and taught me to think for myself and to question everything. He also gave me some of my first records to listen to, which were mostly classical. I still love "Pictures at an Exhibition," and even set that suite for a 15-piece jazz band many years ago. I really wanted to pay tribute to him, as I realized with the onset of Alzheimer’s, he wasn’t going to be around forever.

His absolute favorite music was Bach. He used to laugh that it was ironic that as a Jew, his favorite music was about Jesus. I decided to try and write Bach-style chorales using Jewish scales, to create a music specific to our people, and that was how the project started. I ended up writing pieces that highlighted different points in his life, including coming to America, meeting my grandmother, and finally his battle with Alzheimer’s. It’s sad to me that by the time I had written and recorded most of those pieces, he had completely lost interest in listening to music and didn’t respond to it at all. I know he would have been really proud of me, though.

Photo: Dominick Mastrangelo

Photo: Dominick Mastrangelo

What drew you to the bass clarinet as your key instrument?

The bass clarinet might be the instrument most closely associated with the avant garde, with its strong ties to Eric Dolphy, the great experimental multi-reed player. It doesn’t have much of a history in the straight-ahead or classical worlds. It still, to this day, feels like an outsider instrument, with most of the general public still confused as to what the hell it even is when they see it.

I’ve noticed people who are attracted to its unique sound are, unsurprisingly, attracted to unique sounds. The difficulty of the instrument requires a commitment that might deter people from dabbling with it. I immediately fell in love with the instrument, even years before I played it. I was just learning reeds and saw one for sale in a music shop for cheap, so I figured why not?

I love the range of the instrument. I’ve always loved low sounds. I played the electric bass in high school and college. The low notes on the instrument, especially the ones with the low C extension, are amazing. It’s also really expressive in the higher register too. Melodies sound beautiful on it. Bass lines are great. I played for many years in a bass clarinet quartet in San Francisco called Edmund Welles, and we performed a lot of covers. It became clear really quickly you can play almost any style of music and imitate almost any instrument with it. Even instruments you wouldn’t think of like drums and strings. It’s an extremely flexible and diverse instrument.

What evolution as a musician do see across your recorded works?

Every album or project for me feels like a chance to try something new. If I don’t learn something from a project, what’s the point? It’s easier to pick one “thing,” learn from your mistakes and just refine, refine and refine that one thing into a shiny, well-oiled machine. There are definitely artists who build great and long-lasting careers doing just that, just trying to write a better version of the last piece they wrote. That doesn’t interest me as much personally, as a composer or as a listener. I love artists that take chances like John Zorn, Eyvind Kang, and more recently, Ben Lamar Gay. It’s harder because everything you do that's new has a greater chance to fail, and failing in public can be embarrassing.

I’m not sure how I’ve specifically evolved, but I know I’m not as scared to try new things anymore. When I first transitioned to more rock-oriented stuff, like for the Simulacra album I made years ago, I thought people would laugh or not take me seriously, but I don’t worry about that anymore.

In 2013, you spearheaded the live revisitation of Fred Frith’s 1980 experimental classic Gravity. Reflect on spurring that project into reality.

My good friend and bandmate Dominique Leone and I were sitting around talking one day, and he mentioned that he’s always wanted to play Fred Frith’s first solo album Gravity. I felt the same, so we decided to contact Fred to see if we could look at his old charts for the album. We both knew him peripherally. He did some guest guitar work on my Tzadik album, but I wouldn’t have called us good friends or anything. Dominique asked him and also threw in at the end an invitation to join us. He got really excited about the whole prospect, and it became clear pretty quickly that this would be a fully-collaborative effort between the three of us, with Fred managing the reigns.

Since the album Gravity was recorded using a different backing band for each side—Samla Mammas Manna was the band for the first side, and The Muffins were the band for the second—I thought it would be cool to have my band Thorny Brocky do the first side. I had the violin and accordion and a lot of the sounds from that band, while the harder-hitting Muffins side would be better suited to Dominique’s band with Ava Mendoza on guitar, Jordan Glenn on drums and myself with the low reed bass lines. Fred immediately ditched that idea, feeling like there was too much happening on each track for only a handful of musicians to cover. So, the band became a combination of both bands, plus the addition of William Winant on percussion, and Wobbly on sound effects and electronics.

It was pretty tense going into the first rehearsals. At this point, Fred was understandably skeptical about pulling this music off live. He actually didn’t think it was possible. He told me if it didn’t sound good after the first day of rehearsals, he reserved the right to cancel the whole project then and there. I didn’t want the band to know how razor thin the chances of this thing working out were, because they had put their lives on hold for a full week of rehearsals, and many of them would have bowed out if they thought it was for nothing. So, I was caught in the middle, trying to impart on them that we needed to sound great on day one with Fred, without them feeling like I was being too much of a controlling asshole about it. It was pretty stressful.

I was also slated with the job of making sure the charts were correct and playable. Samla Mammas Manna learned all that music by ear, apparently in one day, which is mind-boggling, but needless to say the charts were mostly sketches. I don’t think Fred remembered what the charts were like, so I was in the dark on how close to the record he wanted the pieces to be. We ended up rehearsing three times before we met up with Fred.

The first day of rehearsals was nerve wracking for me, because like I said, I wasn’t sure if we were going to last even a few hours. But we set up, and started running the music. After two hours we made it to the end of the entire record, and Fred had a huge smile on his face. At the time I didn’t know that he thought what we had just done was impossible, but it was clear from that moment forward this was going to happen. We played the show at Slim’s in San Francisco, and afterwards he gave us all huge hugs and let us know he was going to start shopping the project to festivals. We were all pretty ecstatic at that point for having pulled it off.

I really can’t emphasize how much it means to be able to perform one of your favorite records with the person who made it. We heard so many stories and insights about the music’s creation that were invaluable to understanding an artist’s creative process. It was a dream come true, and friends of mine who saw us perform the album came up to me and told me they had never seen me so happy on stage.

Provide some insight into your own creative process.

I usually write on a keyboard, although that has been changing in recent years. I’ll sketch ideas out, some chords and then separate it all out into different voices depending on who’s in the band. To me, instrumentation is almost half of the composition process. This dictates the sound and feel, and vibe of the music. Once I have that, I’ll usually come up with some harmonic framework or concept to write the music. This could be a harmonic language or rhythmic language—something to give the music a sound or feeling that ties it together.

I’m currently working on a new project that will involve two amplified contrabass clarinets with two drummers. The sound for the music will be loud, metal and free jazz. Pretty intense stuff. But I still want a harmonic concept. Will the music be riff-oriented? Head-solo-head jazz forms? All of the above? I think the clearer the vision going in, the faster the writing process will be. Too many ideas or no ideas will only waste time stabbing in the dark.

What are some of the keys you’ve discovered to help you transcend genre boundaries?

I think blending genres or incorporating influences can manifest in a couple of different ways. I think one can be superficial and another can be conceptual. For instance, when The Beatles incorporated a tanpura into their music, it made the music sound “Indian,” but the music wasn’t influenced by Indian concepts. It was a textural change that had nothing to do with Indian music. On the other hand, you could incorporate Indian rhythmic concepts like tihai and no-one without the knowledge of that construct would think of it as sounding Indian if you were using Western instruments, yet it would be.

I’ve done a little of both. I’ve had bands with a tabla player that was definitely not Indian music, and I’ve incorporated Indian rhythmic concepts like konnakol into my music in a way that sounds nothing like Indian music.

Today, it seems like we’re almost completely in a post-genre world. Almost everyone listens to all types of music and is naturally going to be influenced by what they hear. To force anyone to play in a style as if music stopped evolving after 1960 or 1970 seems so unnatural to me.

The reason why probably has more to do with money and marketing than with artist intent I think. Radio and press still want to keep music segregated, and grants and festivals still play a role in keeping certain types of musicians away from success. It’s too bad, because to me the most interesting artists out there are the ones that are difficult to describe.

Aaron Novik and Anna Webber performing with the O+O+ Ensemble | Photo: Dominick Mastrangelo

Aaron Novik and Anna Webber performing with the O+O+ Ensemble | Photo: Dominick Mastrangelo

Tell me about your San Francisco Bay Area improv roots and why you chose to relocate to New York.

I moved to the Bay Area in 1997 from the East Coast. I thought I already knew everything about experimental music, having checked out both the Downtown scene like John Zorn et al, and William Parker’s more free jazz-leaning cohorts. But none of that prepared me for the Bay. The first gig I performed at had an opening band of improvisers that were playing so little it barely constituted as music to my ears. It ended with the three of them blowing on pieces of paper, and everyone was laughing because it was so ridiculous. All silliness aside, I realized there were more ways to improvise than what New York had shown me.

So yes, I think the Bay Area scene was different. The West Coast has always had a reputation as being “cooler” and smoother, and I can say that the milder weather probably contributes to this. I think there’s more of a European influence to the improvisation too—a little bit more of a contemporary classical influence and not such a heavy reliance on East Coast energy music.

I loved performing in the Bay. I felt very free to do whatever I wanted to and to be myself. I think when the eyes of the world are not on you like they are in New York, there's no pressure to try and have a signature sound or be marketable. There’s a lot of animosity about that, but it’s liberating, too.

After 17 years in the Bay, I came to a point where nothing in my life was working out. My girlfriend had left me, my living situation was coming to an end, and many of my musician friends were moving to New York. One day I realized I could move to New York too, and I wouldn’t even have to meet anyone new to have a killing band. Plus, I had family out here too—a niece and nephew that I only saw once or twice a year. It felt like time.

Explore the beginnings of your life as an illustrator and how the visual and aural mesh for you.

It’s funny because I studied art in college as a minor, but promptly gave it up after I graduated to focus more on music. I only got back into illustrating when I started working on Frowny Frown. I still don’t really consider myself an “artist artist,” but I have been drawing more steadily for about 10 years now, so it’s getting easier.

I made a Tarot deck inspired by Kabbalah while I was working on the Secrets of Secrets project, and I also am really enjoying illustrating a story the great writer Philip Pullman wrote using Twitter a few years ago about bugs. I want to do more drawing projects too and don’t see myself giving up on either art or music anytime soon.

Your music isn’t obvious, isn’t easy and requires significant effort to bring to fruition. Given the difficult economics of the world of music in 2019, how do you make such ambitious projects a reality?

Self-funding music takes a long time. I don’t make that much money with music, so it has to come from other sources of income. I think that’s pretty normal these days. Many musician friends have other sources of income like day jobs and other hustles like teaching or playing corporate gigs. It’s hard in this country to make ends meet regardless of your passion.

I honestly don’t know where the glass ceiling is with this music. Working with Fred Frith made it clear to me that it’s possible, but even for someone like him it's really hard. I don’t think I’ve ever been too closely linked with the business, so I haven’t really had to navigate anything unsavory in that world. I’ve put out most of my music myself, or worked with labels that are really artist-friendly like Tzadik and Porto Franco, so I’ve been lucky in that regard.

Your recordings are available in deluxe physical packaging. Tell me about your commitment to representing your work in the tactile realm in this era of digital ephemera.

I got into listening to Mr. Bungle in high school because I was a fan of Mike Patton. So, I bought their album and immediately returned it because I hated it so much. I thought it was a joke and that it was insulting to serious musicians and serious music listeners. Yet, I couldn’t get it out of my head, so I sheepishly bought it again. And lo and behold, it became my favorite band, leading me to John Zorn who had produced it, and dozens, if not hundreds of other great musicians.

I think the lesson is, when you buy music, you’re entering into a contract with a group or artist that you will give them a serious chance to win you over. It doesn’t always happen, and I wasted a lot of money on bad music, but the things that challenged me the most, almost always became the most rewarding. The bands I still go back to over decades are usually the ones that rubbed me the wrong way at first. Voivod is another example of this. I hated them at first, but now I go back and I hear a band that was so unique that they were in a genre all their own.

Going back to my grandfather, he told me many times when he gave me classical music to listen to that “You won’t get it the first time or even the second time. Keep listening and it’ll click. When it does it’ll be that much more rewarding of an experience.”

We have a listening culture right now that works in direct opposition to this. Everyone has access to so much music all the time that there’s no way today’s listeners will have the time or patience to give an artist the respect of multiple listens. You get a 15-second chance at best most of the time. This leads to a culture in which gimmicks to get people to like and share music dominate. There are many trite covers that aren’t really saying anything deep just to get clicks.

Honestly, I’m not necessarily against streaming as a concept. I stream music too, but the pay scale is obscene. It’s ruining the industry and making it completely untenable to do music as a profession for all but the most popular of artists. I know I’m beating a dead horse here, but it needs to be said because many people still don’t want to believe it. If there’s an artist I really like, I will buy their album. Otherwise I’m an asshole for listening to their music without supporting them.

We’re living in incredibly challenging times. What role do artists have in attempting to restore the balance that other parts of society are disrupting?

I’m probably not alone in feeling helpless in the face of seemingly insurmountable obstacles facing humanity these days. Trump is a symptom of a growing despondence towards what is expected from our leaders in the face of looming existential threats, but I think his victory in 2016 forced a lot of people to reassess their role in the future of the world.

I wonder every day where my time and energy are best used to aid the survival of the human race, and I’m not sure if music is the best way to achieve those goals. I really don’t. I've been way more active politically and think of ways to use music to raise awareness or money for advocacy groups, but honestly I think the best way to fight what's happening in the world right now is to put your instruments, brushes and pencils down and take to the streets and exercise some good old-fashioned activism. Take your ego out of it and fight for other humans, as a fellow human. If there are artists and musicians out there who have enough clout that they can wield their influence to aid in these issues, that’s great. I don’t have that kind of clout, so I'm going to keep my activism alive in every way I can think of.