Donate to Innerviews

Since 1994, Innerviews has provided uncompromising, in-depth interviews with musicians across every genre imaginable. And it does that with no trackers, cookies, clickbait, or advertising.

Your donations are welcome to help continue its mission of highlighting incredible music and artists, without any commercial considerations.

Your contributions will be instantly transformed into stories and videos, and cover hosting and web management costs. Importantly, your dollars will help ensure Innerviews remains absolutely free to all visitors, independent of their ability to financially support it.

Please consider making a donation today by using the PayPal QR code below.

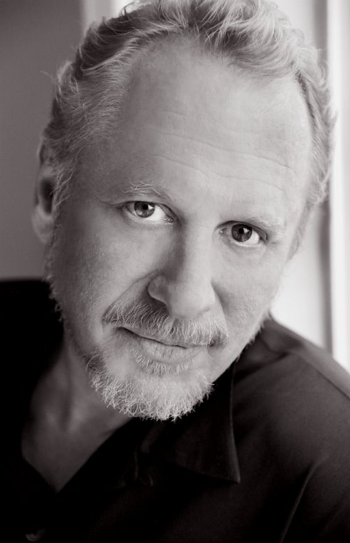

Will Ackerman

Beholding the Remarkable

by Anil Prasad

Copyright © 1998 Anil Prasad.

Tonight, acoustic guitarist Will Ackerman is perched at the intersection where art and commerce meet. It’s a locale he visits often since founding the Windham Hill record label in 1979. This evening, the intersection manifests itself as an in-store performance at the Borders bookstore in Palo Alto, California.

Prior to the show, one ecstatic fan quips "Will’s one of my favorite guitarists. I can’t believe I’m getting to see him play in such a small place—and for free!" A few minutes later, the store’s equally excited music department manager is overheard remarking "We’re gonna sell soooo many CDs tonight." Several displays featuring vast numbers of Ackerman’s latest release Sound of Wind Driven Rain, seem to confirm her expectations, as well as the fact that nothing is truly free on this sphere.

Accompanied by pianist Liz Story, Ackerman takes the stage with a demure and calm demeanor. He’s dressed in a tight, black sweater and faded jeans. Combined with his sun-bleached, curly blonde hair and boyish face, he resembles the surfer dude of his youth more than the 49-year-old millionaire record mogul he is today. Together and solo, Ackerman and Story perform pieces with an emphasis on the signature, low-key balladry that established them as mainstays of the contemporary acoustic music scene.

Ackerman’s influence on modern instrumental music reaches far beyond his own distinguished career as a guitarist and composer. While at the helm of Windham Hill, he played a key role in launching the careers of groundbreaking artists including Michael Hedges, Alex de Grassi, Michael Manring, Shadowfax and George Winston. But listeners and media generally share one of two divergent perceptions of the label. Some acknowledge its initial Ackerman-led grassroots incarnation—a genre-bending outlet for innovation in composition and performance. Others look at it as a yawn factory responsible for the nebulous and amorphous New Age music movement. Anyone possessing a semblance of objectivity concedes the former. However, American cultural myopia rendered the latter description as the most prominent and accepted. Admittedly, since Ackerman sold Windham Hill to BMG, the label quickly descended into the void of smooth jazz—a move that hasn’t exactly enhanced its reputation.

Ackerman cites exhaustion and a lack of enthusiasm for corporate life as reasons for selling Windham Hill in 1992. Later that same year, he went on to found Gang of Seven, a spoken word label that was briefly home to luminaries including famed monologue master Spalding Gray. In 1995, after a non-compete agreement with Windham Hill expired, Ackerman established Imaginary Road, a new, primarily instrumental music label. But unlike his latter days with Windham Hill, Ackerman is not willing to make corporate lifestyle compromises while cultivating the new label. In contrast to his old Windham Hill staff of 80, he now oversees a tight-knit group of five. He also resides in Vermont, far from his former "poodle existence" in Northern California. And when he isn’t pounding out music in his state-of-the-art home studio, he can be found pounding nails into assorted carpentry projects.

But tonight, Ackerman’s focus is building a relationship with the assembled audience—in music and words. It’s a particularly moving performance given its locale. After all, this isn’t any ordinary Borders shop. This particular store was once the Varsity Theater, a performing arts center where Ackerman discovered the late, great Michael Hedges nearly two decades ago. It was also the setting for many other memorable Windham Hill-related guitar concerts. During the late '70s and early '80s, it wasn’t uncommon to encounter Robbie Basho, Alex de Grassi and other local luminaries on its schedule. That’s not surprising given Windham Hill was first based out of Palo Alto, prior to its transformation into the Beverly Hills behemoth it is today.

After the show, Ackerman engages fans in a soft-spoken, charming and friendly manner. The same can be said for his interaction with Innerviews. In this epic-length conversation, he discusses his Palo Alto days, making his new album, paving Imaginary Road, the passing of Michael Hedges and his endless love for carpentry, Erik Satie and surfing.

I understand the new album represents a sort of creative renewal or reawakening for you.

For once in 20 years, I wanted to be able to do something that was melodically self-sufficient. I’ve had so many other responsibilities over the last 20 years that occasionally I fell into what I call "executive music"—I’ll write a few chords and turn to someone else to write the melody. And while it’s true that Phil Aaberg, Paul McCandless and other perennial favorites are on the new record, I felt that what I provided in terms of guitar tracks was really melodic and self-sufficient in every case. I feel that that this record bears more resemblance to It Takes a Year from 1978 than any record I ever did since. I’m actually surprised by the number of people who’ve said the same thing to me. It’s gratifying that the intent of what I had in mind really panned out.

It’s also a more layered and intricate record than we’ve heard from you before.

Yeah, I think the melodies are more sophisticated in most cases, but I’d be happy at any time in my life to have a "Bricklayer’s Beautiful Daughter" or one of those tunes on It Takes a Year. There are a few on here that I think are as good as anything I’ve written. And sonically, it’s a whole different world because of what I have here at Imaginary Road Studios. The microphones and everything else made a big difference. Sonically, it’s a far more interesting record than anything I’ve done. It makes It Takes a Year seem primitive in that regard.

You certainly have the luxury of time and technology on your side now.

Having my own studio and having the luxury of crossing the front yard and working whenever I wanted or when my schedule permitted is pretty neat. A lot of hours went into it. The album may sound simple, but a lot of things that appear simple require a lot of attention to detail. Also, just getting to the point in one’s career where you’ve sampled every mic there is on earth and knowing there is a pair of obscure Neumann 256 microphones that have been bathed in gold—literally—by Klause Heiny at German Masterworks in Oregon to create this incredible sound.

Your technique appears to have evolved as well.

Something happened in terms of my performance that Liz Story was the first one to comment on when we were doing the Borders tour. She said "Where did this come from?" I said "What?" She said "Suddenly, there are nuances in what you’re playing." I’ve always been a touch player, but I think it’s true. I feel poorly about this because I feel I’m bragging. But suddenly, chords that used to be a simple three note pluck I now will natively roll off in a Spanish fashion and it’ll become a four note chord. I’m doing more with how the right hand approaches playing in the classical vein than I ever thought I would. I am also doing a whole lot more in terms of exploiting dynamics in the guitar. Tempo is even more erratic than it’s ever been which makes it a joy to play with me. [laughs] It takes a really skilled player to come in on a track with me because never have I worked with a click track and never will I work with one. It’s wonderful for some types of music, but not mine. I think I’m doing a lot more with volume and bridge dynamics as well. I feel like it’s relatively simple and believe me, from producing Michael Hedges, Alex de Grassi, Pierre Bensusan and other staggering players, I can recognize a great deal of difference between their precision versus what I do. But I think what I’m capable of within my own voice and range is sophisticated to a degree that I’m really proud of.

How did you reply to Story’s question?

I haven’t a clue. [laughs] But I think the answer is maturity. I think during the six year period between records, I found myself realizing that maybe the greatest compliment you can give an artist is to say they have a voice that you can hear two or three notes of and know who it is. I’ve been self-deprecating about what I do because I’ve been face-to-face with so many incredible players. But I’ve also come to recognize that my voice is mine. Rather than feel that I need to be a more chops-oriented player, I accept the fact that those rather modal, very often minor key ballads are what I do best. I think coming to terms with that and being utterly content with that has enabled me to go deeper into what I do as opposed to looking outside of it to cop a de Grassi picking pattern as I did on something like "Remedios" years ago.

What made you feel there was something to come to terms with?

I can honestly say that I’m not natively at all competitive in that realm but I think that it’s inevitable that there is a pecking order. I recognize that there is a cleanliness to what I do, but there is a precision to it too—not a speed precision. It requires a great deal of precision to pull off stuff that is as open to the microscope as my music is. It’s also a matter of getting a little older and being at peace with what you are and not having to jump around looking for something to impress people with. My music is not going to be about flash, it’s going to be about melody and emotional communication. It’s going to be evocative and I hope the melodies and harmonies do become more complex and find chords that redefine. There’s a chord in "Mr. Jackson’s Hat" that was largely improvised and it took me in a whole different direction. I’m not academic enough to explain how that is, but there was a blend in the harmony of that chord. So, I think it’s just great fun to find those things.

How has working with guitarists such as Robbie Basho, Michael Hedges and Alex de Grassi influenced your own work?

You can find a de Grassi picking pattern in "Remedios," "Visiting" and "Conferring with the Moon." There is some influence there. The picking pattern he used so successfully on Turning: Turning Back and those early pieces I did cop. There wasn’t much of Hedges I could cop even if I wanted to. [laughs] I don’t thing I ever tried to imitate anything, but there was the fluid thing to the picking pattern that de Grassi has that I was able to make some use of. You can hear in some of my earlier music and crowd pleasers I still play where I’ve copped some John Fahey. You can hear a little bit of Leo Kottke and a great deal of Robbie Basho. I think there is still a lot of influence from Basho, frankly. His very linear way of playing guitar which treats it more like a sarod—the influence of Ali Akbar Khan for the most part—working in an open C. So much of what I learned was inspiration from Robbie Basho. More than any other player, he’s the one that I studied. It’s true that my approach to how chords are played is more classical than Basho’s. He was content to stay in a really raga-esque place in terms of picking. As my music evolved, I found I was doing less in terms of playing melodies exclusively with the thumb on the third, fourth and fifth string as Basho did in imitating the sarod. I was using chordal stuff more, but the movement up and down the neck is still very much a product of Basho.

Why did you choose to re-record "Hawk’s Circle" for the new album?

I didn’t mean to and had no intention of doing it until stumbling into Samite. [A contributing vocalist and key presence on the album] I was just beginning to throw ideas to him. I think I had been listening to The Mission soundtrack before working on the most recent record and I just got this idea suddenly for "Hawk’s Circle"— that a section could be something like that layered chant, village vocal thing from The Mission. I threw that at Samite and handed him a tape and he walked out of the room and came back an hour later with this amazing vocal part. On one hand it’s a little embarrassing to do the same song for the third or fourth time, but on the other, the song was so radically different. The A section was the quiet section and the B section was the big part. This totally reverses it. The A part becomes the big thing and the B part is almost the rest period. That song itself is such a carte blanche kind of thing. Michael Manring once told me as far as he was concerned, the A section was a piece without a key—that it was really little more than a drone. And that allows me to travel anywhere in the world and have a player put their stamp on a section in my song. It’s always an opportunity to bring another player out of himself and do a duet when I travel, whether it’s a guitar tuner in Tulsa or anybody with any chops or ideas at all.

Corin Nelson played a considerable role in the album’s production. You’ve produced dozens of records. Why did you feel a need to work with another producer?

I trust my own objectivity with my music a great deal and I think I’ve been right most of the time. Corin is a guy that’s worked with me for 14 years. He came in to dig a ditch on the property when he was 16 and in high school and we’ve done everything since, including building barns together—not only for my own property, but throughout the Windham County area. I still sub myself out and do some framing every now and again. A new guy moved in up the hill two years ago and needed a garage for the winter. In November, Corin and I built him a two-car garage. We do a good deal of chainsaw work and gardening. Corin has always been amazingly versatile in what he does and he comes from a background of doing sound and light for theater and when it came time to contemplate doing the studio, he wanted the opportunity to do all the wiring and put the whole thing together.

What was astounding is that this very technical sort of ability could also be augmented in a very positive way with a really musical ear. He can tell when an emotional performance is going down. There are many engineers capable of hearing a click or pop or tech glitch, but few of them have any concept of when anything emotional has happened—when something has been communicated, and Corin has the capacity. The listing as producer was reflective of the tireless work that he did. He accomplished all of the editing. He did most of that and a lot of the musicality of that is because of his attention to detail and ability to help me get to the right emotional place. He would say "You’re hurrying the tempo here. Take a deep breath. Slow it down." He says things like "No, no, no. You’re speeding this up. You want the A to be in contrast to all the others." He’s an emerging producer, but I think that the studio will be a vehicle for him to grow.

You’re that deeply involved in carpentry to this day? That’s surprising given all of your other responsibilities.

Its kind of an addiction for me. It’s almost a joke if you could see my house and do a time lapse to see the additions to the house every year. Last year, there were two small additions and I’m now contemplating two more additions, plus I have a whole new building where I’m doing what I call ‘The Gatehouse.’ I’m getting around at long last to getting a good tractor—which I should have done in 1982. So, I’m building a garage for that and putting a workshop wing off there and a storage area. UPS had a new driver and he called and said he was trying to get acquainted with everyone and figure out where they are. We tried to explain where we were and he said "Oh, by that housing development?" And I said "Well, we are the housing development." [laughs] There’s my wife’s studio, the recording studio, there’s the tower, the dream garage—which is the guesthouse now, the house itself and the garden shed. Now, we’re adding ‘The Gatehouse’—a teahouse out back. This year we’ll also have a greenhouse we’ll put a few feet from the garden room which will give us a chance to grow basil and tomatoes in the winter—a great pleasure.

We recently converted from electric heat which had started as sensible when I was just here in the summer. But in the winter, it got to the point where we were spending $2,000 a month to heat the place. So, we converted to a water circulating heating system. What was the garbage room became the monster room. The monster—a heat source—moved in there and suddenly this room which isn’t even insulated was 80-some degrees on a 30 below night. The idea was "Let’s use that heat. Just pump it into a slightly bigger place and grow basil." Hence, the idea of the greenhouse. So, that kind of thing is constantly happening here. Plus Corin had a house raising in the fall. Sounds like it’s right out of Witness, [laughs] but it really is a part of life here—where 70 people get together on a weekend and erect a house superstructure.

How big is your property?

With Vermont deeds, you never know. Sometimes it’s plus or minus 25 acres, but we’re hovering in the 800 acre category.

Why did the new album come out on Windham Hill instead of Imaginary Road?

My history as a guitarist and my back catalog is with Windham Hill. There is no animosity between me and Windham Hill. They treat me very well to be honest. It was a calculated risk when I sold the company and left my contract with it. Obviously I wrote myself some fairly enlightened contracts before I left. It isn’t like I left myself open to rape and scandal. [laughs] I confess sometimes Polygram wonders why my catalog isn't over here or my new recordings, but to me it's clear. I'm very proud of Windham Hill and its history, plus there's a cross-promotional benefit of bringing out a new recording in catalog sales as well.

How many albums do you still owe Windham Hill?

I think it's pretty much at my discretion.

That's an enlightened contract indeed. From talking to other former Windham Hill artists, it seems not everyone fared nearly as well during the label's shift to BMG ownership.

Oh, I know and I recognize that I occupy a special place in that company. They’ve been very solicitous of my opinion in some cases and I don’t believe it’s for any reason except they really want it. What can I say? I feel I've been treated very well. It's not my company anymore. I can have an opinion as to the direction they might go but they're the ones who have the finger on the pulse of what goes on. After all, it's a business which is owned by BMG and I'm sure that they’ve got the corporate giant breathing down their neck and that’s the nature of things.

How does your A&R approach with Imaginary Road differ to that during your years with Windham Hill?

Chris Roberts with whom I made the deal at Polygram has been a great supporter. On the other hand, I don’t own Polygram. I did own Windham Hill, so I could take any chance I damn well pleased. I think I have to be a bit more conservative and careful to maintain the deal at Polygram which kinda goes counter to my nature. I would personally prefer to be able to bring out three records that I believe in which prove to be duds in the marketplace—not that I ever want a dud or to relegate someone's career to that status. But I would rather suffer that and have an opportunity to do something that came out of left field than to stay in a more conservative realm in terms of A&R decisions. So far, Imaginary Road has had very respectable sales, but nothing that has been considered a hit yet. I would love it if we could put some serious dough in the coffers so we could begin experimenting and begin being a little closer to the way that I would like to do business. We're not in trouble at Polygram with Imaginary Road, but at the same time I think it's going to take a little bit of surplus before I can be as free and experimental as I'd like.

Compare your life and circumstances at Imaginary Road in 1998 to what you experienced with Windham Hill in 1984.

Well, by 1984 Windham Hill had been in a deal with A&M for a couple of years. It suddenly became international. In the early days, we used to joke "Oh yeah, I'll be the president, you be the vice-president" and someone else would say "Oh no! You be the vice-president!" or "You be the CEO!" [laughs] It was just a lark. It was so silly. But truth be told, those names mean something and responsibility goes with them. I found myself being both the figurehead and CEO of the company. I was still signing artists and did far more than I ever wanted or ever intended as administrator. As well, I was living on the road. For instance, if I went to Japan, I went as a touring artist. But I would do 27 interviews a day and it was a multi-level sort of responsibility that ultimately drained me to a tremendous degree. It was something you could probably refer to as a breakdown.

I finally couldn’t do it anymore and retreated to my house in Mill Valley and didn’t come out for months. When I did, it was with the knowledge that I had to resign as CEO and concentrate on music as opposed to administration. I had to get myself out of what I referred to as the "poodle existence" in Mill Valley and get back to Vermont where I can engage in big physical work which has always been my salvation both emotionally and physically in this life. Very simple things such as blood pressure readings indicated to heart specialists that I would be dead in six months if I didn't do something different. Some change had to occur, so I got out to Vermont. To be real honest with you, I was in the throes of something psychological, but now I recognize it as classic clinical depression. I had no energy for anything. I couldn't function at all, but I would force myself up to rake leaves for three minutes on this day, and five the next, and seven the next. Maybe I would move a rock around. I don't want to get way personal here, but the day my mother died when I was a young kid, I went into the garden and gardened for three days. As I said, work has always been my salvation and probably always will be and that’s what I did. I came out to Vermont and after a few months I went back to the doctors in California—the ones who wanted to get me on medication immediately. Originally, I told them "I'm not going to do that. I know what the problem is and I'm going to fix it." But when I went back to California and they put the blood pressure cuff on me, sure enough I was normal. They said "You must have changed your diet." "No" I said. I just worked and reduced the stress in my life.

Look, my wildest ambition was to be the guy sitting on a hillside looking at the Pacific Ocean with a cheap jug of red wine and strumming a guitar for friends every now and again. But suddenly, you're running this thing which is growing 600% a year. You're into the tens of millions of dollars. You have tens of employees. You're flying all over the world and living in a house in Mill Valley that had no warmth at all. It was like living in a dormitory—it was just a place I passed through. There was nothing comforting about it. Contrast that to my life now in Vermont where my day is broken up into rather random pieces, but pieces that I like very much. It may be that there is an hour of gardening, a couple of hours of nail pounding, we may move some rocks around, we'll go into the studio, there'll be some producing, and fax and email. I have the attention span of a three-year-old basically, and for me I just need a great deal of mobility and change.

I recognized fairly early in life that I was unemployable. The only guy who ever hired me said "Look, Will, there’s a house to work on. This goes here and it should look like this. I need it done by July 20." He would crack the whip and say be here at 7 a.m. and I wouldn’t be there. It drove him nuts. He wanted discipline and order and I said "No, you’re not going to get that from me." So he would fire me and then he’d give me another chance. Finally, he said "You just get the job done. I don’t care how you do it." That really says a lot about me. I’m not saying this proudly necessarily, but I just can’t go and sit someplace for eight hours. It has to be filled with seven different jobs for me to be happy which is what I have here—right here. It’s true that I go to New York every couple of weeks and have a good dinner, have a couple of meetings, but then I’m out of there. The travel schedule isn’t like it used to be. It’s workable and I incorporate some pleasure. I remember flying to Tokyo from New York to get a laserdisc award years ago from Pioneer. I remember literally flying to Tokyo, getting to Narita Airport, taking the car into the hotel, going downstairs to the banquet, getting the award, and taking a cab back to the airport and going back. Ludicrous! Here you are in Japan and all you see are two cabs and a hotel banquet room. It’s just a bit saner now, isn’t it?

In May of 1992, you said publicly that you would remain with Windham Hill as long as you could do something effective and have your input register on the corporate radar. Something very interesting must have taken place shortly after making that statement. You sold your remaining interest in the company only a few months later.

There’s an irony to this story. There was an episode of the Twilight Zone I was watching. It was a late night rerun and in it this gambler is caught cheating and is shot. He awakens in what he thinks is heaven. He’s surrounded by buxom blondes in diaphanous gowns and they lead him to the craps table. He wins and then he plays the most phenomenal pool. Then he wins at blackjack and poker. He wins and he wins and he wins and suddenly in typical Rod Serling fashion, he realizes he isn’t in heaven, but in a hell of winning. There’s nothing but winning in his life. I realized that the machine of Windham Hill became that effective. There was another thing too. I went to see Jerry Garcia play when he was doing a lot of drugs I think. He could barely find the strings. He was playing really poorly and the deadheads were just going crazy for it, saying "God, Jerry, man that’s just so great." I’m thinking "What a prison." These guys aren’t demanding enough to expect something of Jerry. It’s just Jerry and that’s enough. Both of those things kinda came crashing down on me and I said "You’ve got to be able to take some chances with your life."

It was getting to the point where I wasn’t even hearing all the records that were coming out on the label. I had very good people working for me: Bob Duskis and Dawn Atkinson. I trust them, but I wondered if that was what I really wanted—to be that distant from the thing and the answer was "No." I began looking at the nature of Windham Hill. Whether I liked it or not, it became a corporation with 80-90 employees spread over X number of offices with a 14th floor office in Burbank which I hardly ever went to. I realized I already was distant from my own company. It was a personal decision. I just didn’t feel that’s how I wanted to be and I didn’t think it was that good for the company either—to have somebody in somewhat of an ivory tower as I was. I was living in Mill Valley away from the whir of the adding machine in Palo Alto and the reality of marketing and promotion run out of Los Angeles. And maybe it was a good thing to have it that way—I sign the artists, you figure out what to do with it. But I felt that maybe I just wasn’t as effective as I had been when I could communicate with people as I like to with mental telepathy and monosyllabic grunts.

I want people that are so tightly knit that they know each other well enough to know what they’re thinking before that say it—with very little communication in terms of memos or meetings. To me, the whole democratization of business is a horrible sign. I’m a great believer in dictatorships or at least benevolent oligarchies. So, I just didn’t feel I was connected as I should be for what the company had realistically become. It was a corporation and I wasn’t treating it as one. I thought I was doing it a disservice and doing myself a disservice by being in a structure that I had never really been comfortable with. The idea of starting a small, tightly knit company is what I wanted—whether that was going into the spoken word business for a little while or eventually creating a brand new music company as a cottage industry again, and that’s what I’ve got.

You’ve also got time to do other things, including writing.

Yeah, I’ve been hired by a magazine to write an article about my truck. [laughs] I have a truck that’s nearly gone the distance to the moon. We’ve been together since 1972. My study at Stanford was principally creative writing and then somehow without even meaning to, I finished the requirements for a history major. Writing has always been very important to me, even if it’s in short and undisciplined spurts like in my liner notes. I’m flattered that a few people, like a teacher at Harvard, are using my writing as a good example of personal essay. I am actually risking something enormous by submitting an article to a magazine, but I’m having one of the best times of my life and would love to find that I could do this three or four times a year. I was actually approached by two different major publishers—Bantam and Hyperion—to write a book about Windham Hill, which I declined to do. I felt to do it properly would mean revealing a lot more of what I regard as private than I want to. I talked to my friend David James Duncan who’s a brilliant author. He wrote The River Why and The Brothers K, and he asked me if I had any compelling desire to just open myself up to this stuff that it would take to make this book really interesting. I said "No" and he said "Don’t do it."

Why not take a step back and simply write a history of the label and detail the philosophies, principles and process of discovery? You could avoid the deeply personal stuff and still create an interesting book.

I have a horror scenario like that scene in Blade Runner in which Harrison Ford is confronting Sean Young with her being a replicant and forcing her to recognize that the memories she was supplied in her memory banks are nothing but that. I find that scene shocking because I have no more faith in my own memory than she had at that moment. Memory is such a flighty thing to me. I couldn’t write an accurate book about the history of Windham Hill. I would be able to write about my memory of the history of Windham Hill, but it would require me to feel comfortable about it and include a tremendous amount of input from a lot of other sources to keep me from creating an entire fiction—not purposefully, but I fear that’s what it would become. The idea of being the editor and moderator of the book and saying "Well, here is my memory of it, does it jive with yours?" could be fun to do when I have the time to do it properly.

When you severed your ownership ties with Windham Hill, you could have devoted your time to writing, carpentry, recording more of your own music or anything else you wanted. What made you want to start more labels?

I didn’t know at the time that I would. I’m glad that I argued BMG down from the seven year non-compete agreement they originally wanted, down to three. Without wanting to sound like Bill Gates, I made enough money in the deal that there’s no compulsion to work to make money. I really love music and finding new talent. I’m deeply disappointed that I didn’t have success with Frank Tedesso. He’s quirky and his voice is odd at best, but to me he's one of the most brilliant songwriters that has ever written a note or lyrics on this earth. So, the opportunity to try with Frank and bring him to the public’s attention sadly failed. I failed miserably, but those are the chances I said I wanted to able to take. George Winston may not seem revolutionary at this time, but in an era of disco, to have a solo pianist who was not a jazz pianist come to the fore seemed impossible.

My handful of distributors at the time tried to discourage me from bringing out the record. They said "You have a nice little folk label here." I bridled about the fact that this isn’t a folk label. I said "I don’t know what you're talking about. It’s a bunch of guitar records. Now you say they’re folk records?" So, why do it again? Because I think I’m reasonably good at it. Because I like producing. If there’s any downside with Imaginary Road, it’s that I don’t feel quite as free to experiment as much as I like. But I just know, sooner or later, we are going to hit it big with something that will give us the flexibility to experiment more. To some extent, I’m waiting for that time. I think if it was me alone, I could be just as chance taking as I want and I believe I would be. But there are other people and livelihoods to consider. Dawn Atkinson and I together own 50% of the label and Polygram owns the other 50%. So, Polygram enables us to do what we want as long, of course, as we feed the big mouth—the hungry beast.

You once said you’d like to put a nail in the forehead of the person who coined the term "New Age." I was really surprised to see that some of Imaginary Road’s own press and promotional material for its Harpestry release uses it openly.

Well, to begin with, Harpestry is a Dawn Atkinson project, not a Will Ackerman project—not that I’m uninvolved. Now, there’s a New Age chart which obviously is an important thing to expose the record and that is a valuable tool. My position is tempered not necessarily by the fact that I accept it any more than I once did, but my emotional reaction to it has softened over the years. The things that created the discomfort in me about the term New Age are two-fold. First, Windham Hill, by many years, pre-dated the widespread use of the term. In fact, we had become a generic term much like Band-aid or Coke. Windham Hill in frustration designed an ad in 1979 that ran in a number of mags which had the words "folk, jazz, rock and classical" crossed out with "Windham Hill" at the bottom. I was so tired of trying to explain what Windham Hill was that the best I could do is say what it wasn’t. Windham Hill was just Windham Hill. It wasn’t as intellectual as all that, but once I saw the ad, I realized really, there you are: Windham Hill is a thing unto itself. It’s really quite different from anything else and to try to define it is purposeless. It borrows from a little bit of this and a little bit of that, but it is its own thing. To suddenly be subsumed into another generic term was something that wasn’t comfortable to me. We had been on our own, self-sufficient and enjoyed this almost trademark piece of nomenclature in the name. So, why would I want to be part of something like New Age?

Secondly, every major label in the world began realizing that serious dollars were going down—that Windham Hill was doing $30-40 million a year. Everybody wanted in and the first thing to do was buy a Windham Hill artist. I was still doing one-album contracts because I wanted it to be a friendship, handshake kind of deal. Suddenly, RCA had their New Age label, Capitol had theirs and everybody else did too. Please don’t think for a second that I’m saying Windham Hill was the only label that ever did something heartfelt or sincere, but I think the mass proliferation of that market was largely a very cynical and imitative move on the parts of the major labels to cash in on a movement they saw taking place but had no knowledge of or emotional connection to. They simply wanted to manipulate it. The market was flooded with product that I think was very confusing to the individual record buyer at the time. There were so many choices. Thirdly, I have to say, the term New Age bespeaks a lifestyle, religious or political orientation that isn’t properly defined. There’s such a range of what New Age is. Windham Hill was simply about music. We weren’t a commune or group of people who gathered together because we meditated the same way. I realize I’ve shot my mouth off enough about it and defined my concerns sufficiently. I’m done with that. Now, I have to live in the real world, just like I had to live in the real world with what Windham Hill had become—a corporation. Sooner or later you have to decide if you’re just going to rail against windmills or accept the fact and get on with it.

What did you make of performing at the Borders Bookstore in Palo Alto that used to be the Varsity Theater? You have a lot of history with that place.

It’s pretty strange being in that physical space in that it’s so completely transformed. I know that I’m in the same space, but it’s tremendously different. The lobby area of what used to be the theater is still recognizable. I grew up in Palo Alto. I went to the theater as a kid and remember winning a model airplane in a raffle when I was 10 or something. So, that space has a lot of memories for me, including meeting and hearing Michael Hedges for the first time and being onstage with Robbie Basho and de Grassi. It had a haunted quality for me.

Any thoughts on the theater’s conversion into a Borders store?

I guess it’s better than a lot of other things that could have gone in there. I feel that Borders is one of the few companies in America that’s still really doing something for music that’s a little on the fringe. So, I’m all in favor of them.

Borders never really struck me as a fringe kind of establishment.

I think they’re working with some of the smaller indie labels and I’m not necessarily including Imaginary Road in that. It seems to me they’re doing a great deal for the new folk singers and instrumentalists. More and more of the Borders stores have real stages and sound systems built into them. Because of that, it’s a viable thing for people to promote what they’re doing. Personally, I think they have sort of taken the baton from Tower Records which has always been great about stocking more obscure records and working with indie labels.

What do you think of this increasing shift towards in-store performances? I know of acts that almost totally eschew traditional concerts in favor of them now.

We’re in a time when booking agencies have become so incredibly conservative. There’s very little corporate support money out there. I don’t know all the reasons for it, but to find a new artist—even someone as compelling as Rob Eberhard Young—an agency is just about impossible. Borders offers a ready-made tour, admittedly it’s not something lucrative, but no-one expects to make money on the road unless you’re the Rolling Stones and have the backing of some condom manufacturer or something.

You told me before the Palo Alto Borders performance that you didn’t want to bring up Michael Hedges because you were concerned about crying.

I had two earlier episodes where I went onstage at the Lincoln Center in New York and began to tell the story of how Michael had bought me my parlor guitar as a gift. I completely fell apart. I couldn’t speak anymore. Then, again, when I was playing at Borders in Portland, I went to do something similar. I mentioned that I had been at Michael’s studio and that later he had brought me this guitar as a gift and the same thing happened. I played the entire song through tears. It’s not that I’m embarrassed to be crying, but I don’t want to seem as if I’m turning it into a dramatic moment. If I know that’s what’s coming, I think it’s best to avoid it. There’s this little story by Kafka called "Leopards in the Temple." Essentially, Kafka says one night, leopards break into the temple and drink what’s in the sacred urn. They then do this repeatedly until it becomes part of the sacrament. I wanted to be sure I didn’t fall into something that was becoming a predictable part of what I did.

You do a "meet and greet" signing session with fans after most of these performances. Have they approached you about Hedges’ passing?

I’ve been struck by how many people came up to me to talk about Michael. He connected with people on a remarkable level. I’ve said this to Hilleary Burgess, his longtime friend and manager. I told him it’s not that I’m surprised, but I guess I am somewhat overwhelmed by the amazing quantity and volume of deeply emotional outpouring that I’ve received from his fans. Whether it’s on the Internet or meeting them at Borders stores or whatever, it just seems like a huge loss to people—as it should be. But it goes beyond just his music. It’s this guy that he was—this person they were so enamored of. I was out at dinner at a local restaurant and the First Ten Years collection was on. We were with friends and "Aerial Boundaries" came on and I had just time enough to say "There’s some of Michael’s music," before bursting into tears. With someone’s death, you’re not weeping for them, you are weeping for yourself. Michael, of course, is so much in my memory as someone from the early days which I think are always the happiest memories of a company or an emerging art. I guess you’re supposed to applaud the years of $40 million of business as the happiest, but for me, the happiest times were Windham Hill in its innocence. Michael was very much a part of that time and part of the building of the incredible momentum this little tiny company with no resources gained by virtue of these incredible talents that assembled almost magically.

The rumor is Hedges submitted some quirky, offbeat project ideas to Windham Hill—things like electronic music, chamber music and heavy rock.

I don’t have any recollection of him having submitted any demos of material in any of those genres. I think he may have dabbled in a lot of stuff and he wanted to always have a rock and roll group. When R.E.M. was happening around 1989, he went down to Atlanta and assembled a rock group around him. But the players were so vastly inferior to him that all they did was drag him down I think. He had a lot of ideas but I don’t think he ever seriously proposed any other recordings other than those that we heard. He had studied electronic music and I’ve heard examples of music he did as a student, but in all honesty, I don’t think there was ever a time when he seriously proposed any one of those projects with the exception of this rock band thing which was just a real failure.

What did you make of his Road to Return album?

[long pause] You know, my favorite record remains Aerial Boundaries and I’m not going to be apologetic about that. I know he made public statements that said we wanted him to make another Aerial Boundaries and I’m very unapologetic about that too. "Yeah, you’re right, you know," I would say. [laughs] When Michael came to visit me in October last year, we talked about the possibility of my producing his next record. I said "I’m under contract with Polygram, but I’d do anything I could to be part of it." And he said something remarkable which I was very honored by and proud of. He said "You’re the only person who can say no to me. You’re the only person who argues with me." I personally feel that whatever levels of genius were in Michael Hedges—and there were many—he was not the most objective self-producer in the world. I would have loved to have had a chance to say no to him on some things and encourage him in some other directions. But what can I say? That could seem very self-serving. It could be seen as "Will produced Aerial Boundaries with Michael and Steve Miller and all he can see is the work he did." I hope that’s not the way it comes off and it’s not what I mean, and God knows he had some beautiful pieces later—but as a volume of work, Aerial Boundaries is uncontested as his most solid and innovative work.

Describe the circumstances in which you heard about Michael's passing and what went through your mind.

Well, Steve Miller—the person who did a lot to shape the sound of Aerial Boundaries—he and I had a bit of a feud in Billboard Magazine a few months earlier. And of all people to call to tell me, it was him. In a way, I felt it was lovely that Steve and I at that important and momentous moment could put all that crap aside and talk very directly and emotionally about the loss of this guy. It was a short conversation and actually put us back in touch and we’ve talked since. Steve explained to me that Michael Manring called Alex de Grassi who called him. He was part of a web who were going to his closest friends that knew him. And again, when you’re crying, you’re not crying for him, you’re crying for yourself. I was also thinking of his kids, and Mindy, and Hilleary, and his new girlfriend Janet. But I suppose, ultimately it is a selfish experience that one has. You just think of the loss of that time, yet the clock continues to tick.

Those events that shaped your history were now many, many years ago—1981 was nearly 20 years ago now. So, it goes into a very philosophical realm. I thought the picture that Windham Hill chose to print as a full page tribute in Billboard was particularly beautiful. It was the one of him sitting in a tree with the cap. It captured so much of his impishness. I thought it was a charming and appropriate choice—not so much the guitar gunslinger, but this very wood sprite guy which was definitely a part of his character. In Acoustic Guitar magazine, I was quoted as saying that I almost take the music for granted which is kind of a stupid statement, but I actually mean it because my memories of him have so much more to do with the guy he was. He was such a compelling human being and the music was just "Oh, yeah, of course." What can you say that hasn’t been said already? The point for me was the loss of this guy who lived life really quite as James Dean would have liked to have lived it. He was kind of an edge character.

Can you be more specific?

We’re reticent to talk about it a lot because we all regarded this as a private matter. I will go so far as to say that all aspects of life appealed to Michael. He didn’t receive all his inspiration from butterflies and sunshine. He was capable of finding power and interest in the human experience that wasn’t all about beauty. I always felt he was very honest about that and that he was a far more interesting and complex person because he wasn’t just doing a New Age psychobabble on people. He really saw life as a powerful thing in a lot of different forms. I’m sort of beating around the bush. There’s no single horror story that I’m obscuring in this process. It’s not as if there was some deep dark secret of Michael Hedges. He was just capable of finding inspiration in a wide range of human experiences and I think he was deeper and better for it.

When performing, your eyes are usually closed and you almost seem to trance out. Give me some insight into the process and what you’re experiencing.

There is almost no mental process and that’s the whole point I think. I need to start back a little bit and describe my writing method. I’m loathe to call it composition because that implies a certain amount of academic understanding of what one is doing. I begin by going into an open tuning and almost always it’s a brand new tuning. I think in my entire history of all the songs that I’ve written, I believe that only "Anne’s Song" and "Hawk’s Circle" were in the same tuning. I think what I’m doing is creating a completely unknown landscape for myself so that the writing process is one of improvisation and discovery—I don’t know where I can find any chord and there’s nothing predictable. I have to explore and rummage around and find it. That removes pretty much any intellectual component. It’s true that I can’t help but know there are certain patterns in creating harmonic structure that I can count on and I have my own sort of tablature that I use in my mind. But the point is that you start writing with a blank canvas without an intellectual process at all. The writing stage almost becomes alpha state to me—you know, closing the eyes. And it’s not that I think "Oh, now close my eyes," but I need to be transported emotionally in order to write and it’s this process of finding a two-, three- or four-note chord thing that I repeat and repeat almost like a chant—but not a vocal chant.

Next, I begin to branch out and then I’ll take a chance on a chord here and chord there and if it works on that path, then I follow it and then go back to the chant. Very often, I’ll develop three different themes in the process with that chant at the core of it and then find the transitions between those things and create a structure from those things that I improvise. I think that at my best in performance, I am recreating the time of writing. I’m feeling that same sense of discovery. I feel that I am the best guitarist I’ve ever been right now. I feel I’m exploring things in terms of dynamics to a degree and subtlety that I had never even known existed before. That always helps me get back to the wondrous time of discovery. That’s what I’m trying to do in live performance. I’m not trying to render the song necessarily as I recorded it, but to find within it the essence of what it meant to me in the writing phase. By exploiting a lot of tempo, volume, bridge placement and chord performance dynamics, I’m able to take subtle chances and hear a nuance in a chord that might be somewhat different which really transports me and I become emotionally involved in the process. That, for me, is everything my music is supposed to be about: emotion and conveying emotion to be evocative and reach people on an emotional level. When it works, it works pretty well.

What comes to mind when you think about Alex de Grassi?

He’s my cousin and we’re both blonde and we pounded nails together, so we have that whole history. I was just at my grandparents’ place which my uncle is now selling in Townsend, Vermont. I was looking at the south wall of the old farmhouse and looking at this beautiful light chocolate brown pine siding that was on it and remembering that Alex and I had nailed that up together in the first carpentry project I had ever been involved in. When I was 12 and he was 10, I can remember us going down to Aptos, south of Santa Cruz during the summer with his sister Gina. We were both older than he was. We grew up together and we had Christmas together, so there’s all that history there. I suppose the greatest and strongest memories come from the point at which the human being who is close to you ceases to be only your youngest cousin—the guy you went to Aptos with—and you objectify him as this absolutely world class talent. I don’t really feel that I understood how important music was to Alex as we went pounding nails.

I do remember that for my 13th birthday, he bought me a Bert Jansch record. Think of how early he was into this stuff being a couple of years younger than I. And when finally confronted with "Children’s Dance," "Turning: Turning Back" and "Luther’s Lullaby" I realized "Oh my God, I’m in the presence of one of the most important guitar figures on earth today. I still believe that. I know Alex has had some success and some fame, but I don’t feel he’s gotten his due. He deserves a bigger place in the book of guitar. He blends a startling technique with a melodic and harmonic sensibility that goes beyond just about anybody. There are so many players who have chops who communicate nothing and he's on the opposite end of the spectrum. His technique, however brilliant, isn't the point—the music is.

When did you first realize how talented he is?

I guess I was too involved in my own myopia of what I was doing. I was aware of the fact that he was playing guitar but I guess it wasn’t really until we recorded him that I really, really came face-to-face with the magnitude of his talent. For quite some time, I encouraged him to record and he seemed not to be interested in it. I tell a story which I believe to be true about my playing at the Seattle Opera House and running out of music and having Alex be there. This was my first paying gig and was for 3,200 people as part of the Bumbershoot Festival. I said to the audience "I really don’t know any more songs, but I have my cousin here who plays better than I do. Why don’t you get him up here?" My recollection is of all these people chanting "A-lex, A-lex, A-lex" and de Grassi getting up there and playing. I’ve expressed doubts about my memory, but it’s a good story one way or another. [laughs] At any rate, his reticence or reluctance turned to enthusiasm about recording and it was then that I began hearing pieces like "Children’s Dance" and was absolutely floored.

How close are you and de Grassi today?

I think you can hear in my voice how fond I am of Alex. I think there were periods when he was this younger person on the building crew and the artist signed to my label, and there was a time when he bridled under the older cousin and my always being the one who in one sense or another was in charge. Certainly, that didn’t leave any scars on me and it’s not at all an issue with us at this point. There was probably a point where there was bit of a rite of passage in our relationship where he needed to manifest himself as utterly independent of me. He might not even consider it an issue at all. He’s so talented and together. You know, I actually find the myopia of musicians deeply irritating. I think a lot of them need a good spanking. But Alex is not one of those. Alex is a wonderful, bright, philosophical, ethical and articulate character. I'm impatient with the western and European concept that says artists have to be irresponsible fuck-ups and incapable of doing anything but playing music. Alex is someone who is tremendously well-rounded and capable on so many levels. He's able to talk about agrarian economics in Scotland in 1840 and a vast range of other academic and intellectual themes. He has more than just music in his life and that makes his music richer.

Describe the glory days of the Palo Alto guitar scene that you and de Grassi were a part of.

Do you know The Village of The Damned? It was a horror movie that was made when I was 12 or something. The gist of the story is there was some odd event that took place one night, but nobody really knows what it was. There were lights in the sky or something like that and nine months later, babies would start being born with the same look in their eyes. It ended up that these eyes would glow and be able to zap you. So, the alien had invaded them and taken over the fetuses of these pregnant women in town. One night, something similar happened in Palo Alto with guitar. I don’t know what in the name of God it was. It’s like the epicenter of some sort of earthquake that happened in the guitar and contemporary instrumental music. There are too many lines that cross through here in Palo Alto to make it not seem almost spooky. You have the genesis of the whole New Age thing, but especially the reinterpretation of the guitar. There was me and Alex, but there was also Rich Osborne, Frank Rollins, Alex Kilmarten and George Winston. Robbie Basho said that one of his objectives was to take the steel string guitar, which had traditionally been a folk instrument, and give it a classical discipline. Bert Jansch and John Renbourn had begun to sophisticate the guitar already too. So while it’s true the Palo Alto experience wasn’t utterly in a vacuum, there was something there that made the guitar leap forward in terms of its range, sophistication and its move towards a type of classicism.

I think all of the names that I mentioned were part of it. Rich Osborne would knock off guitar pieces that would tear my head off in college. I was such a babe in the woods next to his complexity. He studied with Robbie Basho as did Frank Rollins and the others. We were also aware of John Fahey, Leo Kottke and the Takoma school of guitar, but were all playing and sharing ideas very openly. My first gig was really playing in this arch on a Stanford campus. I would usually do it on a Saturday night. It was just a beautiful, reverberating space. People would know I was going to be there and sometimes I would play for 180 of them. There was never any money exchanged and these things would go for hours and hours into the night. Brooks Yaeger and Rich Osborne would come and play, and it was like Paris in the ‘20s. It was a clearinghouse of musical ideas and we tested them on the people who came and listened. It wasn’t a high pressure situation, but you were conscious of performing and I really cut my teeth on this space with friends and accomplices who were exploring what the guitar could be. The Palo Alto and Stanford University area spawned some of the most important guitar players—some who are utterly unknown like Rich Osborne. You could do a whole album of early Palo Alto guitar. It’s almost spooky. How did that all come together in one place?

Let’s talk about a couple of your key influences. Expand on the role Robbie Basho played in your development.

Robbie Basho was an angel. I don’t believe he was terrestrial. I would watch him play and be transported in a way I’ve never been transported before. I’d see him have conversations with people who I did not see in the room. I truly believe that his reality was more accurate than mine. He was seeing a spirit that I was not. I think he may have died a virgin. Robbie didn't have a driver’s license. He was not of this world and was not equipped to be part of this world. I’m not surprised he left this world early. It must have been very tiring for him to try to be in it, but his influence on me is so vast and seminal that I can’t possibly overemphasize it. I think people should go back and listen to his music. There’s some powerful, powerful stuff. Though his voice was odd, it was so powerful. I never really studied with Robbie. I wanted to but I was just too undisciplined to do it and at some point Robbie, exasperated, said to me "Oh, so you need the short lesson." I said "I guess so," and he said "Don’t be afraid to feel anything" and "Sing every melody out loud. If all you’re doing is guitar riffs, there won’t be enough there." Very often a guitarist thinks he’s playing a melody when all he’s doing is a chordal progression with a picking pattern. Unless you can sing the melody as an independent thing and have it work as a melody just note by note by note, you haven’t really written a melody. It’s one of the greatest exercises to engage in when writing. It was a tremendous tool that he gave me. He lived on a spiritual plane that was very real and he made beautiful, beautiful music that people would be well served to listen to today. Doing records with this man who I revered was a big deal for me.

I understand the work of Erik Satie also occupies a special place for you.

In the world of music—the entire spectral host of music—there is nothing more important in the world to me than Erik Satie. Nothing has moved me more. Nothing has influenced me more. There are so many things in your adolescence that touch you and you go back and go "I dunno." But Satie has always been there for me as a source of wonder. I admire the man’s bravery in a time when he was surrounded by Debussy, Ravel and that milieu. Instead of going the academic route, he had the guts to write these incredible, spare, Zen-like quirky pieces even with all those influences around him. I think there is no piece of music more perfect on earth than "The Gymnopédies." I produced a record of Erik Satie piano solos. It went gold in Japan.

I’ve heard Rob Eberhard Young, an acoustic guitarist signed to Imaginary Road, has an upcoming release that you’re really ecstatic about.

I think he’s the most exciting guitarist I’ve heard in 15 years. He’s making a record in Santa Fe which has the potential to put guitar in a whole new direction. It remains to be seen what will come out of the sessions, but from what I’ve heard, he’s making some rhythmic grooves on the guitar that are more compelling than anything I’ve ever heard on acoustic guitar in my life.

That’s quite a statement, especially coming from you.

Yeah, but it's absolutely true. It remains to be seen what the final form will be and whether it’ll have all the pieces. But he’s on the verge of something absolutely remarkable and I hope he gets there.

From a business and artistic perspective, you’ve accomplished a great deal to date. Are you content with your life as it stands today?

No, I’m not content. I’m capable of great happiness and I don’t think my mental state is by any means manic. I don’t feel I have a chemical thing going on in the brain, but I’m capable of and engage in fairly wide mood swings. I think that’s part of the artistic temperament. I don’t encourage it, but as with all things in life, without death there’s no appreciation of life. Without sadness, there’s no appreciation of a really happy moment. What I would like to say is that therapy has rendered me this person utterly content with himself. [laughs] That certainly isn’t the case. My greatest happiness comes from nature and from beholding something that is remarkable in other people or in creation. My wife is a painter whose work is on the cover of the new CD. I am watching her evolve and I’m coming to realize that the experience of painting is almost the same as writing music. Obviously, there are great technical differences, but she has a voice in her art and it’s an amazing thing for me to see this develop in her and see this talent just looming right next to me. It’s the same experience I had with Alex [de Grassi]. "Oh my God, right here in this person is something that is world shaking" and that’s truly what I believe. I love that. I love seeing that emerge and I think I’m really quite good at nurturing it and encouraging it and that I’m capable of recognizing artistic voice in areas outside of music.

I’m toying with the idea of a children’s art gallery. There’s a writer who lives in Boston who among many different things has done collections of quotations from kids along with kids’ art. Some of the pieces are as graphically beautiful and powerful as anything I’ve ever seen in any musician in the world. Just because it’s innocent doesn’t mean it isn’t valuable. I’m not one who has a lack of ideas and interests. I wish I had time for all of them. So, am I content? No. Do I have a lot of happiness in my life? Yes. Do I also have demons and do I have periods of tremendous fear and sadness? Yes. Thank God for the outside world. Thank God for Vermont. Thank God for physical work. If I couldn’t go out and clear land and thin forests and build another building here or build a barn for someone, I would just die. And I love surfing too. I love waves and that’s maybe my happiest thing.

My wife asked me the other day "If you have six healthy months to live, what do you do?" I said "I just go around the world and surf all my favorite breaks and places I haven’t seen." That’s the most Zen experience I know of because the wave and your relationship to it changes constantly. It is so addictive that my wife is sometimes out on a point in Hawaii yelling at me "Do you realize that it is dark and that you are surfing to the moonlight? Do you realize you have been doing this for 14 hours?" She said a little voice will come out of the water that says "No." It’s just one more ride, just one more ride. You are so in that moment—more than anything I’ve experienced in my life. There is no room for reflection. It’s one the most beautiful things in my life. So, I don’t want to portray myself as someone who is evolved or enlightened because I’m not. I take great pleasure in this life and in the people in it and the beauty. In that way, I have a lot of happiness.