Donate to Innerviews

Since 1994, Innerviews has provided uncompromising, in-depth interviews with musicians across every genre imaginable. And it does that with no trackers, cookies, clickbait, or advertising.

Your donations are welcome to help continue its mission of highlighting incredible music and artists, without any commercial considerations.

Your contributions will be instantly transformed into stories and videos, and cover hosting and web management costs. Importantly, your dollars will help ensure Innerviews remains absolutely free to all visitors, independent of their ability to financially support it.

Please consider making a donation today by using the PayPal QR code below.

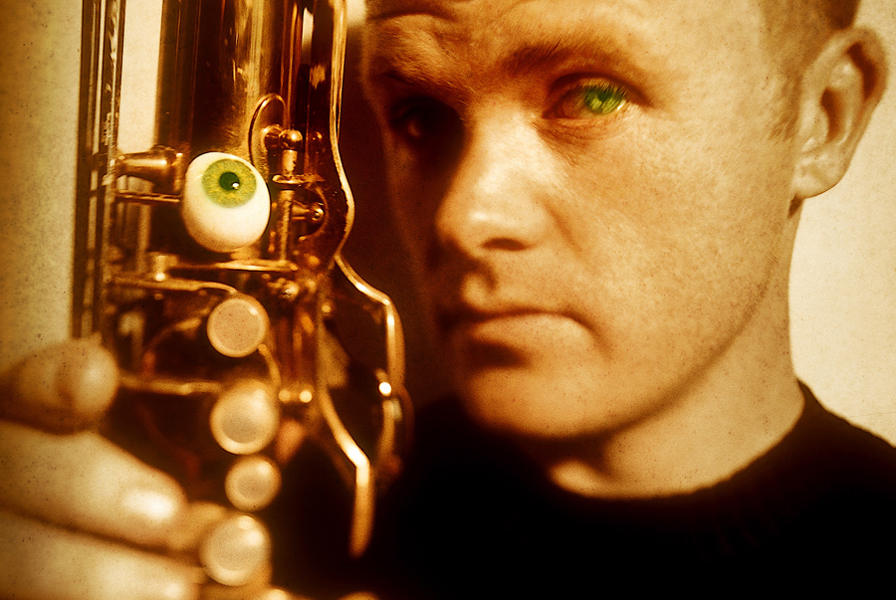

Iain Ballamy

Converging Philosophies

by Anil Prasad

Copyright © 1993 Anil Prasad.

What’s the point of music? Why is it necessary? Those are a few of the questions that went through British saxophonist Iain Ballamy’s mind when Innerviews encountered him in the summer of 1993. He was in the midst of a string of Montreal Jazz Festival dates with Balloon Man, his highly-regarded acoustic jazz quartet featuring multi-instrumentalist Django Bates, drummer Martin France and bassist Steve Watts.

Ballamy’s philosophical bent partly stemmed from the circumstances he found himself in. He’s a world-renowned musician, having played and recorded with the likes of Loose Tubes, Human Chain, Bill Bruford’s Earthworks and Billy Jenkins. He’s also performed with Balloon Man across the globe to rapturous audiences. Yet, at the time of this interview, he was without a record deal and the representation his talent deserved. His main pillar of strength was a self-driven, uncompromising motivation to explore his art form — a scenario that encouraged a reflective mindset.

Since this interview took place, Ballamy signed with B&W Music. To date, he’s released several albums as a leader, including Balloon Man, All Men Amen and Acme. Each collection offers up a combination of lush balladry, lyrical playing and the occasional fiery number. His collaborations with Bates also continue in groups such as Quiet Nights and Delightful Precipice.

Let’s start by discussing your musical history.

I was born in 1964. I started learning music on the piano in 1970. I carried on playing piano, but I lost the interest as kids often do. I ended up doing it because I felt guilty that my folks had paid for piano lessons. When I was just about 14, I took up saxophone after having heard someone in rehearsal playing it. I just got switched on overnight. It was a guy called Brian Merritt. He's completely unknown in America or Canada. So, he helped me out. He wrote me a fingering chart and I kind of taught myself. I had like three lessons when I was starting out. I left school when I was 16 and I went to a two-year course in college to learn to build and repair musical instruments. And then when I finished that, I became a professional musician.

I was 18 when I started doing odd gigs like in pubs, theaters and bars—wherever I could. And that kind of built up slowly. In 1981 and 1982, I went to a jazz course for one week hosted by Johnny Dankworth, an English saxophone player. There's an organization which puts on jazz courses and I met a lot of people there who, in fact, I still play with. It was quite a jumbo crop of people who actually turned out to be on their way to becoming professional musicians. I met a lot of the tutors there too. From meeting the tutors, I started to play with one or two of them. And then one of those tutors recommended me to a bass player who was playing with Django [Bates]. So they called me up. I did some rehearsals with them, but it didn't work out very well. At the time, I couldn't even read music. I was a sort of self-taught player although I could play bebop reasonably well though.

Then I got an offer from a venue. They said If I got a band of young guys together, I could have a gig every month. So, I had to think of who to use. I remembered Django, so I contacted him. At the time, he already had a good trio together with a bloke called Mick Hutton on bass who used to be in Earthworks, and another guy called Dave Treadwell who was the drummer. I got a trumpet player too and we started playing typical Joe Henderson, Herbie Hancock, mainstream post-bop jazz—Maiden Voyage stuff and tunes by McCoy Tyner. Django was already writing his own stuff and he said to me "Look, why don't you just write your own music? You know you can write good music. It's more fun to play your own material." So, I wrote my own music, and we got a radio broadcast. It worked out really well. It gave me confidence to carry on. In the meantime, Django was writing music for larger groups. We both found ourselves involved in a jazz workshop that met once a week. Every week, different people would come and take the workshop with their material. It would be John Warren one week and Graham Collier another—people like that. We were called something ridiculous like the So-and-So Jazz Workshop Big Band.

Eventually, the band outgrew the situation and kind of flared up. People started writing music from within the band. And then the guy who was our administrator became the manager. Then we came up with this name from within us—Loose Tubes. And that was really where my jazz education came from. Loose Tubes started in 1984 and went until 1990. In the meantime, I had my own band together. And then Bill [Bruford] heard my band and liked it. He offered me the chance to put a group together with him to go to Japan, which we did. And then we made the first Earthworks album shortly after that.

Why did Loose Tubes break up?

At the time, England was in the beginning of the economic crisis that we're in now. And having a 21-piece band during those conditions, coupled with the fact that any band that doesn't have a director or a leader as such, means there's always going to be differences about how things should be done. Nobody could hire or fire people. Maybe some people stuck out more in that band. There were other people as well who contributed like Eddie Parker, Steve Berry and Chris Batchelor. They wrote some nice music for that band. It kind of reached the stage where the band had to change a lot—and nobody could change it—or it had to end so something new could come along. And that’s what happened.

I understand you're not very happy with the last Loose Tubes album.

There were quite a few compromises involved with that record. I think it probably was our first bad experience with a label. It didn't work out very well. We were going to do another album for E'G, but they pulled the plug about a week before it was to start. Everyone was so screwed up by that because everything was under one roof for awhile. In the late 1980's, there was Balloon Man, Human Chain, Loose Tubes and Earthworks. We were all in the same E'G camp. Anyway, everything changed very rapidly when Loose Tubes finished in 1990. My band changed personnel in 1988 to the line-up it is today with Steve Watts [bass] and Martin France [drums]. They were in Loose Tubes during the last year or two.

Currently, you’re working with Bates in several bands beyond Earthworks and Balloon Man.

Yeah. I joined Human Chain in February of this year. I'd never been in it before. It's always been something separate that Django has had—separate from my involvement with him. We've been involved in so many other projects that it just made sense at this time, logistically, to combine. We also play together in Delightful Precipice, an 18-piece band that plays much larger music—a la the best things about Loose Tubes. It's more rigorously controlled—the quality control is much higher. This band has five saxophone players, two trumpets, trombone, French horn, flutes, tuba, clarinet, bass, drums, percussion and keyboards. I play alto and soprano sax.

You also record with Billy Jenkins on a regular basis.

I first started playing with Billy in 1985, just before Earthworks. I've made quite a lot of records with him. In total, those six or seven albums I made with him have ended up selling 5,000 copies—the lot of them. Probably even less. It's really, really small. He's got one CD now which is like a kind of compilation. He did a survey of all the fans and asked them what they'd like to see on CD.

Tell me about the time you spent in South India performing with the Karnataka College of Percussion group.

That's a band that Charlie Mariano regularly plays with. He's a saxophone player who lives in Germany now. I was doing a tour with the group, which plays traditional South Indian music with a singer, tamboura, ghatam and a mridamgam. They use a funny electronic tamboura which is like a droning box that simulates strings. I got a chance to do a tour with them because Charlie's mother was 100, and he couldn't miss her birthday, but he couldn't cancel the tour. So to learn his music, I went to South India and had an intense crash course in Karnatic classical music. I also had a week looking around Madras and Bombay. So, that was nice, but you need more than a fortnight to even dent a subject like that.

Earthworks must pose an interesting dilemma for you in that it’s often playing for audiences not well-versed in jazz.

Yeah, that was quite difficult. I mean, we had the audience, but when we first started it wasn't quite necessarily the audience we wanted. I remember we played in the Commodore Ballroom in Vancouver. That was a weird night. I remember there were lots of people who were clearly expecting one thing and leaving with another. And obviously there were some people who liked it and other people who didn't. On subsequent visits, people knew what to expect, so the people who came were people who liked the band or people who were up for something different.

Describe your working relationship with Bill Bruford.

Obviously, there's a lot of difference in where we've come from. We've come around to playing with Bill from a completely different starting point. Earthworks is a meeting point. It's a converging of philosophies and creativities. For instance, if I meet a Japanese piano player in Iceland and someone says "You two play a tune together," we know that if we've got a tune in common and we both know how to play, then we can make music together. Even if I've never met the guy and I don't speak a word of his language and vice-versa. There are big differences in every band. I think every band has a chemistry. If something good is going to happen, I think there has to be creative tension of some kind or just a balance of people.

Compare what you're doing with Balloon Man to Earthworks.

Earthworks is more of a fusion band, with the difference being that Bill plays electric drums and Tim plays electric bass. In my band, I've got acoustic bass and drums. That's the major difference. Also, the music in Earthworks is co-written. In Balloon Man, it's solely written by me. It's a looser band. Earthworks has a lot more written material and a lot less flexibility.

Who are some of the musicians that have inspired you throughout your career?

When I started, I was originally very turned on by early Fats Waller because I was still playing piano then—playing "Alligator Crawl" and things like that. And Scott Joplin. When I first started listening to jazz, I didn't like bebop. I couldn't handle it, but I liked West Coast jazz—Stan Getz, Paul Desmond, Chet Baker—that kind of cool jazz. Then I got into bebop. I listened to all the typical people—Fats Navarro, Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Miles Davis, Bud Powell and Charles Mingus. I followed that through into the 1950s and then went in a fairly logical order to [John] Coltrane, more Miles and Miles with Herbie [Hancock]. Also, Herbie’s albums into the 1970s. And then I got into Weather Report. I stuck around that period for awhile and then went shooting back to the 1930s and 1940s trying to catch up.

There are other things too which I didn't appreciate when I was younger. I got massively into Steve Grossman, Bob Berg and Mel Lewis' Orchestra. Joe Lovano was in that band and I liked his playing a long time ago. I got into [Duke] Ellington and Johnny Hodges. For the first time, I could appreciate that. There was Lefty Young and Ben Webster too. And then, after that, I got into free jazz—Charlie Haden, Dewey Redman and Keith Jarrett and the whole ECM thing. Then I kind of rejected everything and decided that I'd done a lot of listening and now it was time to be more interested in it as a player sport rather than as a spectator sport. As I got more involved with the people I was playing with, they influenced me more. I became very devoted to people like Martin France and Django and other people in Loose Tubes.

What are your perceptions of how jazz is characterized today in popular terms?

That's a difficult question to answer because so many people are into jazz, but when you try to figure out what they like, it's a strain or a breed of jazz. Everything has to be kind of pigeonholed these days. Calling something jazz is like calling a large amount of the color spectrum by one name. If you want to go into detail, you have to talk about what type of jazz rather than arguing about whether it's jazz or not. Let's just accept that people use that word to describe hundreds of different sorts of music, and then you don't have to treat it as a whole thing. So, to answer that—where I think it's going in popular jazz—there's a big retrospective movement which always seems to exist. There's the nostalgia factor which is recreating, in a way, what was alive in its essence in the moment 30 or 40 years ago. I don't have a problem with that. As long as the music has a freshness about it, it's not a problem.

There's two kinds of traditions going on in jazz. One is the tradition of moving on, trying something new and experimenting—not swirling around in the past. The other is kind of like what's happened in classical music where Beethoven's been immortalized—and now Gershwin. The more people play standards, the more that tune, that show, or that film becomes like classical music. The more times people record "Porgy and Bess," the more it's going to become like "Beethoven's Fifth." It's the same as playing jazz from 30 or 40 years ago—Miles' style or whatever. So, the music is quite confused. I know marketing people who are able to deal with retrospective jazz better than contemporary jazz. And also the listeners are better able to deal with it because they've had 30 years of Miles filtering into their subconscious. Now, they've heard it so many times on the radio they feel they can relate to it at last, whereas, a lot of people at the time weren't hip enough or open enough. It just happens all the time in art. Nobody can expect to make it until they're very old or actually dead, and then it's okay to like someone.

Can that be changed?

I don't think it can, really. I think that's just the way it is. Even this music I'm playing which is new to the Montreal Jazz Festival is not new to me. It's all new and exciting for the people hearing it for the first time, but we've been playing it for six or seven years. That's why I came here not having any expectations—because I've been doing this for quite some time.

You’re often positioned as a young lion with great potential by the music press. Is it frustrating to have them refer to you in the future tense?

People often say that and quite often those they say it about are great in 20 years. And sometimes it takes people that long to see that what they're doing now is great as well. It takes time. People need time to catch up. I don't really think about it. Obviously, I'm aware because I don't have a record deal. I made my Balloon Man album five years ago, and I'd never have believed that five years later I'd be in the same position looking for a deal with a band that's been working steadily. In a way, it doesn't surprise me. I try not to think too much about that shit. I get on with the music and let other people do the hypothesizing and the criticizing. Otherwise, you just pump yourself up, that's all. It is frustrating though. I can't believe Django's been so long without being signed. There's been kind of mumbled interest from Blue Note, PolyGram and EMI for years. I just can't believe he hasn't been snatched up.

The problem is they don't know where to stick you if you play too many types of things, you look a bit strange and you don't play the game. When there was a bit of a jazz revival in London—and I use the term lightly because people who play jazz carry on playing it all the time and always have—a lot of people got signed who didn't have anything much to say. They were given huge budgets to make records. Of course, after dishing out lots of money on huge advances, record companies were losing lots of money and expecting pop-type sales for pop-type budgets. They ended up getting their fingers burned. In the meantime, a lot of people didn't have a deal before or after that, and they're just chugging along doing what they do. In some ways, I think the record side of things is as confused as it's ever been. They don't want to take a chance.

It's really hit and miss apart from labels like JMT or ECM. For them, there's someone who very carefully guides what's going on, keeps a catalog of material and keeps it available to the best of their ability. Instead of head-hunting, it's like cataloging music for the future. It’s about that, rather than spotting out an artist that's going to be big now—like Courtney Pine who’s done a lot for the music in England. He's appealed to a lot of people from outside of jazz. He's brought them in, got their foot in the door and it's given them a chance to check out his music. And if he mentions this or that or where he's coming from musically, people with inquiring minds will check out other styles of music. Also, if you look like a jazz saxophone player and you play as a jazz saxophone player is supposed to play—in a style people have heard enough to have a familiarity—then you stand more of a chance of getting recognized by a record company and ultimately being put in the record shop and bought. So. it's got a lot to do with whether or not you look like a saxophone player.

I know some people look very much the part and act very much the part—whatever the part is. But so many people don't. It's like if I dress like James Dean, you know what I'm doing. I'm going for a James Dean look. I wear those clothes and get my hair cut and wear the jacket and go around looking all James Dean. Some people don't do that. Some people don't give a shit about that stuff—it's just not what they're into. They're into whatever they're into, but it's not always so easy for other people to get into it. Some musicians are into entertaining. They consider themselves to be entertainers while other musicians don't set out to entertain. That disagrees with them, although they don’t mind if listeners find them entertaining. Some people will argue and say "That's really selfish—that's like musical masturbation on stage" and all that sort of thing. Some people think that if you're a musician, you're supposed to be a theatrical artiste. For some, you're there to entertain people and they are there to be entertained. But others are there to hear music and they like to see people making music. It's not necessarily about entertainment in the same way.

Are you surviving okay in this climate?

I'm happy to say that as a single guy, I'm able to make enough money playing the music I like to survive without being totally panicked. I'm hovering somewhere above the magical line. I'm not in debt, but if I stop working for three months, I will be. If I get sick or something for three months, I'm going to be in trouble. So, it's kind of like that. As long as I'm able to play, I'm fine. Maybe I could survive for six months without working, but then I'd be in money trouble without selling my coin collection and stuff.

For now, I think I'm fairly content. I'm very much into the people I'm playing with. Obviously, I'd like to record more. I'd like to go into any store in America or Canada and see an album that I'm on available in the shop. This is not the case at the moment. I'd like to see my own album available in the shop. At least one record in the store would make me very happy so at least I know people can buy it if they want to. I don't mind if no-one buys it. It's just that I'd like to know that they could if they want. I get traumatized going into record stores. It's completely overwhelming you know—there's so much product there.

I also like to make sure I keep other things going in my life so I haven't just got music. Music is not everything. It's the best thing, but not everything. I've found it's a good way to live your life. I like the fact that, as a musician, you are able to travel and whilst traveling to these places, you are able to take something with you. It's an offering as opposed to just going around consuming everywhere. It's nice to take something there with you and share it. That feels good to me to be doing that. It's getting more and more interesting for me to play music now. Now, I can actually play the instrument reasonably well and have some depth and experience—not enough though! [laughs] But now that I've got some of that, it starts to become about other things. It's not about whether the band's tight or playing the right notes or the right music or whatever.

I'm starting to get more into the psychology of music on stage and between the musicians and the audience. I think a lot about the philosophy of being a musician—music and what it does and what it means and why it's necessary. Why music? You could consider it a luxury item. You know, it's music, but what's the point in it? It's like sport—what's the point in sport? Sport gives people a lot of enjoyment. The interesting thing about music is it has massive meaning with people. It connects with them and this has been going on for centuries. Musicians travel and play to people and touch them. And they're fed and watered for doing that—being given shelter and then moving on to the next gig. The modern version of it is a musician out on the road, traveling from place to place and staying at hotels. They get paid and they buy their food with the money they're paid, whereas musicians in parts of Africa or different societies like that may still play for a chicken.

The commodification of music is much less of an issue in those cultures than it is here.

But the role of the musician is still the same, even in the modern world. Pop music is kind of different, though. It's become kind of gross in itself. In some ways, the whole music industry puts a different slant on it. For instance, at this festival, I've heard a lot of really good musicians from Montreal. And I know what it's like if you're the local talent and you get shoved in a corner playing in a club or whatever. I know what that feels like because we suffered from that a lot in England. I mean, in England, they fucking hate us. "You can't have jazz with electric drums" and whatnot is what they say about Earthworks. They don't like it. So, we mostly work in Europe outside of England. It's the problem with being indigenous musicians or whatever. It's like in Australia—the kangaroos are just regarded as a fucking pain, but everywhere else in the world, they go "Australia: Home of the kangaroos." It's the same thing. I think you can only get recognition at home when you've made it outside and people say "Hey, this is really big." Then people say, "Oh, I know you, you're brilliant." Well, of course they are, but they're the same as before. You earn your credibility. It's like everyone is looking everywhere else to know whether it's okay to like something. That goes on a lot.

I've heard one of your hobbies is metal detecting.

Yeah. I’ve found loads! I found a Bronze Age sword earlier in the year near where my folks live in Surrey. It was all smashed into pieces like scrap bronze. I’ve also found millions of coins and artifacts—anything made of metal you can detect.

Do you go detecting on tour?

No, I don't take it around with me. It's enough embarrassment at home much less taking it abroad. [laughs] But they've got good metal detectors at the airport. I've always enjoyed going through them. It's like the detective becomes the detected! [laughs] I'm quite into my hobbies. I ride horses and I hang out with a lot of friends who are artists in other fields. I've got a very good friend who's a stone-carver, and he carves abstracts. His name is Michael Yanson. I've got another friend called Michael Bode in Hamburg who's an installation artist. In fact, that tune of mine, "Mode Forbode" is written for him. He makes sculpture and installations out of anything he can find. He's a very interesting bloke. And then I've got friends who are silversmiths, those who do sculptures and other things—people who do mosaic floors and tiles, illustrators, people who write poetry, painters, and stuff like that. So, I get turned on to a lot of things outside music. A lot of my friends are quite inspiring in other areas and that creeps into my life as well.

It’s time for the burning question. Why don't you like small, barking dogs?

They get under your feet. I like dogs, but they have to be above a certain size. Well, at least the size of a terrier. And chunky. And short-haired. I don't like long-haired dogs. You know how you quite often see middle-aged ladies carrying little dogs around? They've all got little dog-coats on, and they're trembling, and they bark at you because they feel overconfident or something. Anyway, I just don't like them, so I decided to write "Rats On Stilts." And then when I upgraded it about five or six years later, it became "Rats On Stilts II." It's sort of supposed to represent the way they walk.

Any other thoughts before we wrap up?

I’d like to ask everyone to keep an open mind. Don't always go for the easy choice. There's a lot of music out there and the only way you can get ahold of it is if you look around. Once you get your foot in the door and discover there is that music there, you find there's interesting stuff. It's like books. You go to a store and there's Jimmy Cooper novels, Stephen King novels, Thomas Harris novels and things like that. But as usual, the more obscure, less commercial stuff, you have to look a bit harder for. Check it out carefully. Don't always buy the first thing you see on the shelf. I'll give you a funny example. I went to this party a couple of years ago and I was talking to this girl there. She said "Oh, I saw your record when I was in the record shop the other day." I went "Great. Did you buy it?" And she said "No, no. I bought a Chet Baker album instead." And I said "Hang on a minute, I'm listed right next to Chet Baker. Why did you buy the Chet Baker album instead?" And she said "Because he's so handsome!" [laughs]