Donate to Innerviews

Since 1994, Innerviews has provided uncompromising, in-depth interviews with musicians across every genre imaginable. And it does that with no trackers, cookies, clickbait, or advertising.

Your donations are welcome to help continue its mission of highlighting incredible music and artists, without any commercial considerations.

Your contributions will be instantly transformed into stories and videos, and cover hosting and web management costs. Importantly, your dollars will help ensure Innerviews remains absolutely free to all visitors, independent of their ability to financially support it.

Please consider making a donation today by using the PayPal QR code below.

Bill Bruford

Smashing Sacred Cows

by Anil Prasad

Copyright © 2019 Anil Prasad.

On July 31, 2008 at Ronnie Scott’s in London, Bill Bruford played drums for the last time in public with Earthworks, the jazz group he led for 22 years. His decision to retire was influenced by challenges he experienced in both the creative and business realms, chronicled in detail in his 2009 book, Bill Bruford: The Autobiography. The news came as a great surprise to millions of listeners worldwide who had immersed themselves in his output with Earthworks, Bruford, King Crimson, Yes, Genesis, and UK. A world without his instantly-identifiable, deft percussive touch seemed unfathomable. Yet, the decision was made, decisively and immutably.

Earthworks’ final lineup featured saxophonist Tim Garland, bassist Laurence Cottle and pianist Gwilym Simcock. It was the acoustic culmination of a fascinating, ever-shifting journey that began with a jazz-rock bent in 1986. Its initial formation included Bruford on a hybrid electro-acoustic drum kit, Django Bates on tenor horn and synth, Iain Ballamy on saxophone, and Mick Hutton on upright bass. The group established Bruford as a father figure within British jazz. He became known as someone who gave young musicians a real shot at an international career. Bates, Ballamy, Simcock, and pianist Steve Hamilton are all examples of musicians who went on to pursue their own formidable paths as leaders, post-Earthworks.

Throughout its existence, Earthworks combined influences far beyond jazz and rock. Classical, folk, funk, Arabic, North African, Flamenco, and Balkan music were just a few of the other genres the group integrated into its sound across five studio albums and four live releases. The entirety of its recorded output, as well as concert DVDs and rarities, was just released as a 24-disc box set titled Bill Bruford’s Earthworks Complete. Of particular intrigue is From Conception to Birth, a disc with 17 tracks showcasing the evolution of Earthworks’ material from demo stage to final master recording.

In addition to curating his extensive catalog as a solo artist on his two record labels Summerfold and Winterfold, Bruford has spent his post-retirement time pursuing a doctorate in music from the University of Surrey, which he completed in 2016. He’s now focused on writing within academia and conducting lectures across Europe and North America.

In 2018, his third and most recent book, Uncharted: Creativity and the Expert Drummer, was published. It’s an adaptation of his PhD dissertation that offers insight into the practices, behaviors and psychology that inform the output of upper-echelon drummers. The book offers perspectives from his own career, as well as those from Peter Erskine, Mark Guiliana, Dylan Howe, Asaf Sirkis, and Chad Wackerman.

Earthworks, 1986: Mick Hutton, Iain Ballamy, Django Bates, and Bill Bruford

Earthworks, 1986: Mick Hutton, Iain Ballamy, Django Bates, and Bill Bruford

What story do you feel the new box set collectively tells about Earthworks?

It tells the complete story. There's nothing left out. For me personally, I suppose it's a personal mission. It's lovely to have these differences in the performances, and the different songs by different ensembles, all tickety-boo in one place, complete with live material, this, that and the other. The fourteenth title, From Conception to Birth, shows you the origins of some of the songs and so forth. It's a very complete, very full meal.

What are the highlights of the group's output for you?

It all has its quirky flavor. Most of the time it seems fairly workaday, what the drummer's doing. There are some large conceptual leaps. I think the early hybrid electronic-acoustic drums are good. I think the idea of three guys at the beginning of the band's output, with three single-line instruments, bass, a tenor horn and tenor saxophone, supported by chords from a drum kit, is good.

Do I like one track over another? Let's think now. I would say there's something lovely about Django Bates' song, “Candles Still Flicker in Romania's Dark” where the whole band works well, although it's very slow. I also like the acoustic version of the band that I think came in with albums like Footloose and Fancy Free. The Sound of Surprise was also a nice album which I loved, but it sold poorly. It’s my favorite album, actually. It’s balls-y progressive acoustic fusion, with strong melodic content, recorded with the amounts of time and care usually not given to jazz groups. In other words, we had a fairly good budget, which was great.

What was it like for you to initially pursue and work with young musicians in Earthworks who didn’t know anything about your rock background and weren’t in awe of it?

I think that was great. Once in a while, on an annual basis, musicians should put themselves under a cold shower and be in some sort of territory in which they're pretty uncertain of what's going to happen next and not even sure whether or not they should even be in that position. Calling up a bunch of British jazz guys, who as you say, had never heard of Genesis or King Crimson, was perhaps an unusual stretch. And from their point of view too, probably unusual among their community as it were, to cross the divide.

And trust me, in 1986, the divide was still there between jazz and rock. I think looking back in 2010, nearly 25 years later, we smoothly allied jazz and rock. We know that drummers are more interested in drumming generally rather than any kind of apartheid sense of jazz versus rock or the question of is rock louder and better than jazz—or any of that stuff. We got past that. But in 1986, I think that was still there. So, I think there was a jazz community which didn't know about rock, and a rock community which didn't know about jazz. Happily, many of those barriers have broken down since.

Provide some insight into the intrigue of these two realms colliding back in 1986.

What was strange from my point of view is that the band had to audition for EG Records, and go into a studio and play “Thud.” There was pressure and maybe we did a demo. Then we had somebody at EG say, "Yes, okay, we'll give you a small budget. You can get to work for Virgin Records." Having come from what I thought were fairly big groups, I kind of imagined the manager would say, "Yeah, all right. Whatever your thing is." On that level, it was unusual.

I was astonished by the competence of the other guys in the band. The ability that jazz people have, which is lovely, is to play things in a different way. It’s never the same way once, as they say. I like that a lot. In rock, it tends to be one way and one way only, and you have to continually be reminding people what it was like last Tuesday, which was the last time they played it. Could they play it the same way again, or could they play it at all? Jazz is done very quickly, and I did like that a lot.

Earthworks, 1989: Iain Ballamy, Django Bates, Bill Bruford, and Tim Harries

Earthworks, 1989: Iain Ballamy, Django Bates, Bill Bruford, and Tim Harries

Django Bates told me you invoked a phrase called “stadium jazz” to encourage the band to play with more space. Elaborate on what that phrase meant to you.

Clarity. There is a tendency for music to naturally fit the rooms in which it's being played. So, you have at the huge end, the slow plod of Pink Floyd, which suits the 20,000-seat room it’s in, admirably well. At the other end, you had in 1985, British jazz in front of 15 people in a tiny room, or perhaps three men in a pub. The musicians tended to scrabble around on their instruments without consideration of how that music was coming across.

And I'm right between the two. I understand that at times it takes the number of notes it takes to make something work well. But I also understand the effectiveness of music in a room. I know because I wrote a piece with Django. Django commented on the forcefulness and directness of the drummer. I wasn’t like the other drummers he played with, who were able to toy more and perhaps be more flexible with space and dynamics. When you're playing a noisy American rock room with 500 people in it, you will have to simplify your language, clarify and make the notes unmissable from the back of that room, I think, like any actor would.

Are there any tunes in the early repertoire that you would point to as emblematic of the stadium jazz approach?

What works well is the slower music, for sure. Broadly speaking, the slower the tempo, the better. We never played very fast music. There was a Steve Hamilton tune called “Eyes on the Horizon,” which had a very fast tempo. I probably wouldn't have suggested we play it in a 2,000-seat room in Santiago, Chile. “Footloose and Fancy Free” is going to work well with a 5/4 backbeat. “Candles Still Flicker in Romania's Dark,” with all that space in between events happening, is going to work well. You see what I mean? It's not rocket science.

One more phrase both you and Bates use when discussing the early Earthworks period is “smashing sacred cows.” How did Earthworks do that?

Perhaps I give us too much credit. But first of all, around 1986, plugging in was dangerous. Plugging anything in is dangerous if you want to be a jazz musician. It's conventional wisdom that an upright bass has an upright bass drum accompanying it. How's it going to be if you have an electronic bass drum and the electronic bass drum changes its characteristics as the music goes on? These are smashing sacred cows, particularly. They're skirting round the perimeter of what's normal. When you play at the jazz club up in Yorkshire, people will look at you rather strangely when you're doing these things, and if it gets too strange, you won't get invited back, of course. So there's an element in which you need to bring the audience with you, for sure. Some of these things worked better than others. As the electronic drums got better, they were easier to handle. They were very difficult to start with.

Earthworks, 2001: Steve Hamilton, Bill Bruford, Mark Hodgson, and Patrick Clahar

Earthworks, 2001: Steve Hamilton, Bill Bruford, Mark Hodgson, and Patrick Clahar

By the time Earthworks Mark II emerged in 1997, the group was a known entity. The musicians understood the opportunities and potential the band offered. Did those facts inform the chemistry and ambitions of that lineup?

Yes. We also had much more standard jazz quartet instrumentation, which was nice, too. I mean it's always a balance between you do something for a while and see where it'll lead you, if it leads you anywhere at all. I think what the first band led me to was pretty much a broken drum kit given its reliability concerns. It also led to the logistic impossibility of running a quartet at that kind of overhead and that kind of management system. We were doing one-nighters in Barcelona and Madrid, and it was difficult and complicated. I think probably I was just looking for a quieter life when we moved back to acoustic music. Acoustic music is very nice in many ways. In lots of ways, it's as lovely as hybrid electronic stuff.

One of its overwhelming advantages is that a piano is not really going to change its tonal characteristics halfway through the song. The vast amount of decision-making necessary to make the halfway-hybrid electric thing work all evaporated overnight. Suddenly, I was up there with Steve Hamilton on piano, Patrick Clahar on tenor saxophone, Mark Hodgson on upright bass, and acoustic drum kit, which now I can rent, you see. The group became financially viable again if you can have your drum company provide a kit or your promoter will rent you a kit or something. Don't ever underestimate the impact of finances on things. You get what you pay for. You get what we can all afford to do.

Also at that point, musicians were clamoring to join Earthworks. It was established as a group that provided significant performance opportunities for young British jazz musicians. How did that change the dynamics of recruiting for you?

Yeah. We had an audience, for sure. We were five albums in. We had a posh booking agency out of Boston called the Ted Kurland Agency and we were making tracks. There weren't that many British groups going to the States. Musicians were emailing me or phoning me as you would've done in those days. Generally speaking, nobody I approached said no, so that was good. Usually, someone said something like "Have you tried this young, great Scottish jazz pianist?" Towards the end of the band, Tim Garland knew everybody. I didn't really know so many jazz musicians, but Tim brought Gwilym Simcock into the group, which was heavenly, and probably pointed me to Laurence Cottle. Steve Hamilton suggested Patrick Clahar, I think.

So, you find these guys and you realize they can play well beyond the requirements for the band. Their technical level is high, they seem to be sober, are available, and not too bogged down with too much baggage about jazz or what it should or should not be. In other words, prepare to be flexible. If you found people like that, as Hamilton, Clahar and Mark Hodgson were immediately, then I think it's likely to work. I'm not going to go ‘round London or even New York and ask for other names of musicians who might “do it better.”

In 2000, Larry Coryell subbed for Clahar during a Spanish tour. What was it like having him in Earthworks?

I still wonder why we did that. It originated from our booking agents from the Ted Kurland Agency, who were also managing Larry. We were looking for summer festivals. This would've been a booking agent's idea of heaven—that he could get their solo guitar star Larry Coryell to have Earthworks as his backing band and we could launch out onto some European jazz festivals. It would make a better European jazz festival buy. I saw the commercial logic in that, but I'm not sure I saw the musical logic. Somehow, hearing Larry play “Bridge of Inhibition” was something of a shock, and I think it shocked Larry too. Give him his due. He really worked at the music, which didn't come under his fingers easily. But I think we were a little bit oil and water as two ways of approaching music. It was just one of those experiences. Not a particularly successful one. I think we also played the Pizza Express in London. It was a summer thing. I think at the end of it we were probably happy to go our own ways.

You dismissed a band member or two along the way, including Clahar. What factors were required to be a long-term member of Earthworks?

Jazz groups don’t have terribly long-term members. Most people learn a fair bit about themselves and/or the music they want to make when they're in Earthworks, and that may crystallize during their tenure. They may say they want to move on and try something new and that seemed perfectly right to me. That's partly what the band is for—to find yourself and find your direction, and inevitably you will move on.

At the end of Patrick’s tenure in 2001, the primary thing is that I was pretty much exhausted with running the band and trying to write the music. Patrick didn't write. Tim Garland did, who I was close to at the time. Tim is a major writer and composition is one of his favorite kinds of operations. He said he'd love to write for the band, and I said, "That's great. That means I don't really have to do that." I think writing for me was more of a chore that Tim took on with great pleasure and alacrity. He has all the music training necessary to make it relatively effortless, whereas I tended to struggle.

Earthworks 2005: Tim Garland, Laurence Cottle, Gwilym Simcock, and Bill Bruford

Earthworks 2005: Tim Garland, Laurence Cottle, Gwilym Simcock, and Bill Bruford

After 2001’s The Sound of Surprise, Earthworks’ subsequent recordings were all live projects. Discuss the reason for that.

Yes, The Sound of Surprise was the last album we did in which we gathered in a studio and the clock was ticking. And that's halfway through the band's career. The reason for that is to do with the fact that the cost of sitting around in a studio had become impossibly high. Certainly in a London studio. The cost and pain of recording live was relatively minimal.

When you decide “Well, let’s record it live,” really, it’s effectively what you also do in a studio. But in a studio, you get a second go at it. When you record live, you don’t get a second go at it, and I kind of liked that. I got into the swing of recording live, whereas when I was a young man, recording live was seen as a poor second best to a studio album, for sure. In jazz, recording live is every bit as good as, if not better than a studio recording. King Crimson was somewhere between the two. Some argue that its live music was better than its studio music.

Garland convinced you to bring some of the Bruford jazz-rock material into Earthworks. Reflect on transforming it for the acoustic format.

He did, because he grew up with that and loved it. The Bruford material had a different quality, entirely. Sometimes effective, sometimes less good. “Seems Like a Lifetime Ago” worked very well as a quartet without singer as an instrumental version. “One of a Kind” missed the grit of a Jeff Berlin or an Allan Holdsworth, I think. Perhaps it was too fussy in arrangement for it to be particularly successful, but we probably didn't play these things more than three or four times. It was more or less a request from Tim, really, and we happened to be recording around that time in 2003 at Yoshi’s in Oakland, California. It wasn't a big deal. We learned the tunes. They're not very hard. People like Hamilton and Hodgson were very quick and very good. Tim managed to transcribe a fair bit of it, which also helped no end. It was more like a bit of fun, really.

What is it about the 2002 show in Santiago, Chile that made you want to include it in the box set?

What I like about it is it was in a big room with a big audience. The South American audience that King Crimson, Bruford and Earthworks had was substantial. It was absolutely amazing. They're so generous. It's quite astonishing how many people would turn out to hear Earthworks down in Mexico City or Santiago. The recording was available and I wanted something that put that quartet to bed as it were, because we were coming towards the end of the box set. It seemed like a cracking CD and DVD set to have on it, so we went ahead and used that.

In 2004, Earthworks Underground Orchestra—a nonet version of the group—briefly existed. Tell me about that period.

The album we released in 2006 is one of my favorites of that time. We had great American players in that group, which I loved. I thought that was a real privilege. Tim more or less took the helm on that. He said, "Come on, we can go to the States, and there are guys there in Manhattan who will play for peanuts and a big smile. They stay in Manhattan and you don’t ask them to go on tour, because the price is going to be unaffordable. But for a few nights at the Iridium, people are willing to play if the music’s good.” That was wonderful, so we did that. I think that was a smashing band and I would've loved to have done more of that, but it was not to be. That would be about the last thing we did.

Earthworks Underground Orchestra, US lineup, 2004

Earthworks Underground Orchestra, US lineup, 2004

How do you look back at Earthworks’ final show at Ronnie Scott’s in 2008?

I wasn't going to leave this planet without leading a band at Ronnie's, which is something I really wanted to do. There have always been in my mind certain milestones which are fun in terms of live performance. I think you've probably got to play the Blue Note somewhere, you've got to play the Royal Albert Hall, you probably want to play Madison Square Garden, and you definitely want to play Ronnie's. There are these places that are career makers. Having my own band playing our music on a bandstand on which I've seen Rahsaan Roland Kirk and Jimi Hendrix as a kid was a seriously exciting thing to do, and tremendous fun. But I did know we were at the end of the band, and I was at the end of my performing career, so I suppose there was a bit of nostalgia about it certainly.

I was probably also anxious. The anxiety grew too much for me and that more or less prevented me from continuing as a performer. I persevered happily until the age of 60, but at the age of 60 I wanted to collapse over the finishing tape and drop the drumsticks, because there was a level of performance anxiety that I'd achieved that was making life intolerable. Somewhere after Ronnie's, it was no longer possible to do those kind of performances, so that was fine by me.

I wasn’t sad. There was a sort of exaltation. It was fantastic doing it. It was lovely to go out with a bang. It was that kind of feeling. Simultaneously, I was relieved at not having to do it anymore. I'm not one of these people that makes music easily, as you're probably beginning to understand. I envy those from whom music seeps out like water. It seems to be effortless for Tim Garland, Gwilym Symcock and Laurence Cottle. These people are so familiar with musical material that it appears effortless. I'm aware that probably to other people it appeared effortless in my case, too. However, It wasn’t effortless and it definitely took its toll on me. After 41 years I'd more or less had enough.

What thoughts were going through your head as you put down your drumsticks for the last time?

I'd love to give you something that read really well in the Daily Post, but I'm afraid I can’t. [laughs] It was a good gig. Three-hundred people were applauding at Ronnie’s, so it was great. I had a sense of a job well done, that I’d been a musician for a while, and that I was happy to do something else. I wasn't quite sure I knew what that something else was going to be, but that didn't bother me. I knew it would probably have been related to music. I was beginning to think along those lines. But I knew I didn't have enough stamina to keep going. Even now, I look back at the speed that young people move at, and the stamina they need to be an international performer. Let's take a comparably young fellow like Mark Guiliana. The speed he’s working at, the sacrifices he has to make, immediately gives me a headache and makes me feel exhausted. I take my hat off to those young musicians. Whatever they’re being paid, it’s worth every penny.

Describe how the band’s producers during its first few albums influenced its sound.

I’m not sure we really ever used a producer in a conventional sense. The producer was typically a nominal producer, which was me. The level of production involved determining which take to use and when we had done our best. That was the hardest moment.

We worked with Dave Stewart on the first album. I’d say he was a producer in the sense that he and I would decide together what seemed like the right thing to do. He'd say, "Well we could use these samples here. We could interject this sample into that track there. Then the jazz group quartet could emanate from this dense, heavy drum machine-driven music, such as ‘Pressure.’” Dave had great ideas, and was always good with sound. He was a little bit unfamiliar with jazz, and I think generally was a little stiff in that area possibly.

We used David Torn on All Heaven Broke Loose, bless him. I loved David. Such a great guy. He could do things with machinery that gave us aural backdrops, like the harmonizers he used on “Temple of the Winds.” He was particularly good with loops, although we didn't use much of those. He's eternally encouraging, interesting and a lovely person to have around.

After that, it was pretty much me making all the production calls. I should mention we also had a very good engineer named Mark Chamberlain for A Part, and Yet Apart, and The Sound of Surprise. He was a lot of fun. He had worked in rock and was prepared to spend that little bit longer on jazz to make it sound good.

What do you feel From Conception to Birth reveals about Earthworks’ creative process?

I remember being at the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam and looking at these lovely little sketches of The Potato Eater's hands. They were rough sketches of the rural hands of the characters in the paintings. They were drawn quite finely beforehand as a test—as a way of thinking, "Well how important should this hand be?" Sometimes seeing the sketches can be very enlightening in terms of how they informed the end product.

So, I thought these rough audio sketches might also be of interest. It has 16 tracks, with eight pairs in which you hear the demo first and then the finished, production master. The way a demo works within a small quartet that's rehearsing in a rehearsal room is interesting. It’s what the musicians first heard. It was the stuff I played them.

I didn’t write out charts. I would do a demo, play it for the musicians, and they’d agree to play on it. They wouldn’t screw up their faces and say, "God, that sounds awful." They’d give it a go. And before you know it, and after you've done a few gigs, things can sound quite different. It can be a lovely moment.

Once it suddenly comes to life, it means so much more. Instantly, I’d know what parts are wrong and which are right, what’s playable, what isn’t playable, what musicians want to play, and what they can play but don’t actually want to play. Also, you learn how the musicians can make the piece better and how you can include them in that process.

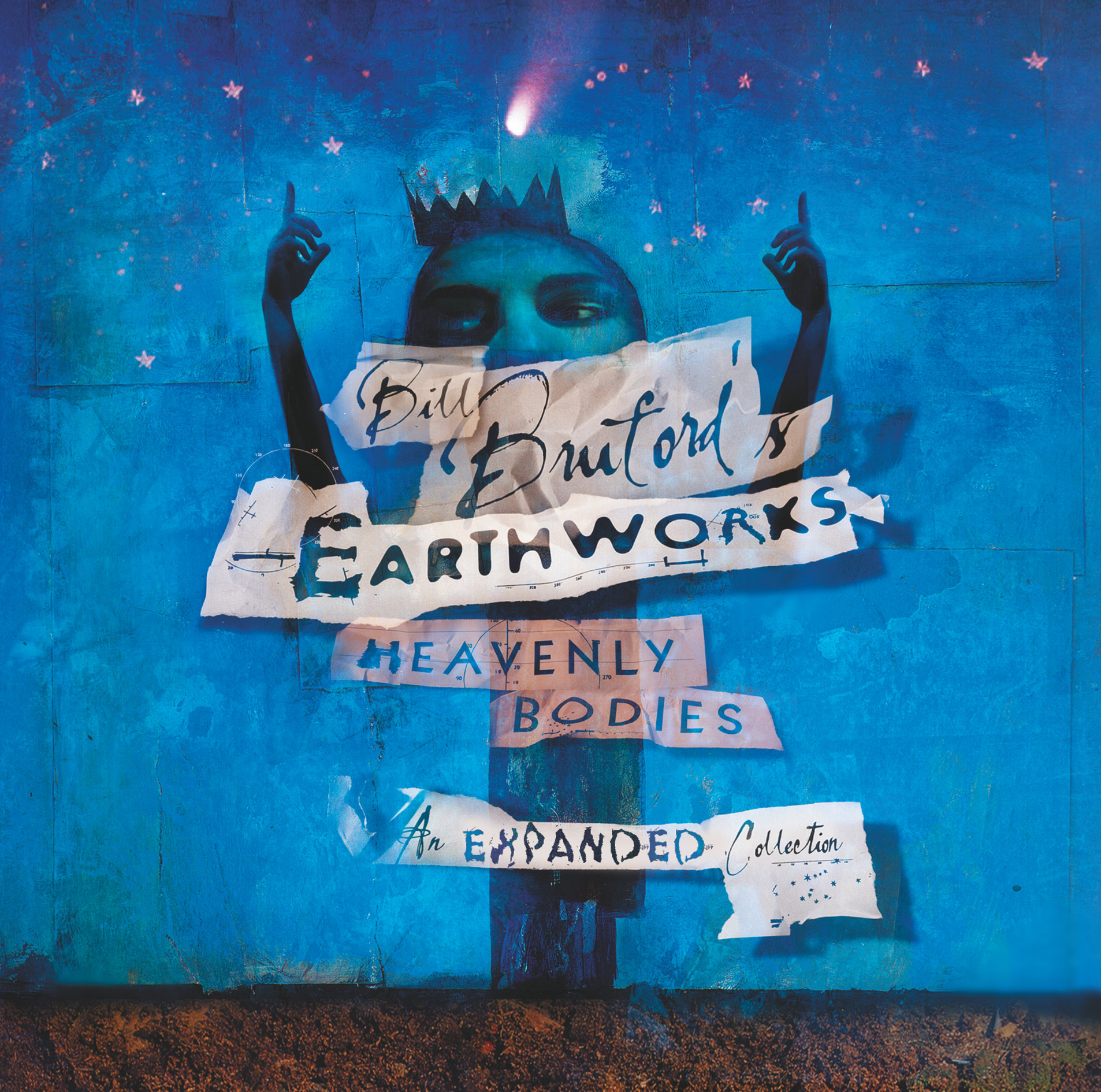

Dave McKean’s artwork has been a fundamental part of the group’s aesthetic, including the new box set. What made his approach work so well for Earthworks?

His work is great. Absolutely tremendous. He captured a quirkiness and a slightly carnival-esque view about the musicians. One of my favorites of his is the Heavenly Bodies cover. It's a blue cover with a blue character kind of conducting the band with a sort of very subtle King Crimson crown with candles on it. These images were so right for Django Bates, Iain Ballamy and myself, particularly. I love Dave’s work. It’s very dark, though.

It helps to no end for a band to have a visual aesthetic that flows from album to album. Happily, we’ve got him on Live in Santiago and From Conception to Birth on the new box as well. Sadly, Stamping Ground, the fourth album, was the first one he was on. The first three albums had artwork put together by strange people I probably didn’t know anything about.

In your autobiography, you said the physical CD was a manifestation of accomplishment for you. Is it possible for a stream or download to create a similar sense?

What an interesting question. For me and people in my age group—bear in mind I’m 70—I think we’re probably of our time. We’re now dinosaurs. We liked to think if we had something we could touch, feel, smell, and had liner notes, that was thrilling. Any information heightened the sensation entirely. It wasn’t only about the audio. It was about the physicality and the aesthetic surrounding it, which was lovely. A download or stream isn’t going to excite me in quite the same way.

I suppose the box set is aimed at a certain kind of person who's interested in complete collections of things—the entire life of a band from the first phone call to Iain Ballamy, or perhaps to a visit to Guildford Jazz Club, which is my local venue. Yes, I am a patron. I’m a token celebrity. It’s kind of a joke, because it’s not a huge organization, but I’m supporting them. It’s where I first met Django and Iain. The first thing I did was go and hear those two boys at that place, so you're getting the whole arc of things from that right to the end. I think some people have heard of Earthworks, and have not been sure where to start. This is certainly a heavy immersion if that's what they would like to do. I would certainly welcome them.

Both Rick Wakeman and Adrian Belew have asked you to consider coming out of retirement. How do you respond to those sorts of enquiries?

Just last June, I was attending a King Crimson concert at the Royal Albert Hall. I thought I was going to have to leave the dressing room because they were imploring me to come up and play “21st Century Schizoid Man” with them. I had to explain that I haven’t touched a drum kit for nine years or so and that it would be very hard to know what to do. I had no desire to do it, particularly. But yeah, people have been very welcoming and encouraging me to come back and play the drums. I’m not that sort of person. I’ve left that alone now and I don’t do that anymore.

I saw Rick at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame induction for Yes in 2017. He was in good form. He also came down to my town and did a charity evening where he played “Life on Mars?” by David Bowie and other pieces that thrilled the local customers. There was a lovely description of him hovering over the keyboard, looking like a contented walrus. [laughs]

Adrian has always been enormously encouraging and very gratifying about my percussive efforts, bless him. We both really love the 1980-1984 King Crimson. It was the one I certainly thrived in. I don't know whether the audience liked it, but I loved it. To see that one go was a shame. But I think Robert was much less comfortable in it. Robert is comfortable now in King Crimson.

Are you ever tempted to compose any music just for fun these days?

No, I don't think so. I haven't written any music, no. I've lost my ability to sort out samples and digital audio workstations and how all that works. I think I was very much an analog guy. I became a digital immigrant rather than a digital native. It took me a while to get to grips with the modest amounts of recording equipment that I had at home. I'm well aware that young people just eat this stuff up for breakfast, which is terrific. I don't have a system here which allows me to make music or create music easily.

I acquired a doctorate from the University of Surrey in 2016. I’ve done some academic writing, which has been amazing, really. I’ve been trying to look at what drummers do and the behavior of popular music instrumentalists and how the music might create meaning for them—all kinds of things like that. Occasionally I do liner notes, like those I just did for Asaf Sirkis’ forthcoming album Our New Earth. So, in that sense, I’m a writer for hire.

Five years before you retired, you told me, "I think how you get out of this should be as interesting as how you got into it." Tell me how you methodically planned your exit from the music industry and performance.

I started to write and thoroughly enjoyed it. I wrote most of the autobiography in 2008 and thought, "I was born in 1949 and I’ll be 60 in 2009.” That felt like a good time to stop. That sounded about right to me. I didn’t want to die in a hotel room. I wasn’t thrilled at going to airports anymore and the general waste of time that it is—the 48 hours necessary to play for two hours on stage. I didn’t have the stamina for it anymore, or the inclination. I felt it was time for me to move on. I would've looked at the writing and said, "Ah, maybe I should ask about publishers." Surprisingly, or not surprisingly, when I retired as it were, or told people I wasn't playing anymore—no more public performance, anyway—I had a book ready to support that and explain a little bit about why the desire to play had kind of drained away from me.

I think the simplest way to explain why I stopped is because I couldn't hear any longer what came next. I don't mean of course the next measure in the music. Of course, I know what comes next in the next measure of the music. I couldn't understand what came next with drum kits, or what would be my next drum persona or my next drum attitude. I didn't know where I should go next with the drum kit, or where should the drum kit go next with me on it? I couldn't see a future—better still, I couldn't hear a future.

Indeed, it's difficult now for young people, because 95 percent of drumming is automated, and there's this five-percent cream on the top of wonderful musicians like Asaf Sirkis, Mark Guiliana and all the other wonderful drummers that are around. But it's hard for them. My heart goes out to them and I support them to the ends of the Earth, because mostly it's producers, MCs and hip-hop and so forth. For sure, I had the best time doing what I did. Why would I want to surf downhill into the bit where it's really, really difficult?

I know many musicians in your age category. Virtually none of them can financially conceive of retiring because they didn’t plan for their future. What advice do you have for musicians who want to retire one day?

Plan for your future. [laughs] You should bear in mind I was very lucky to make money between the ages of 18-21. I had a manager who said, "There's a thing called a limited company. You should be a limited company. And by the way, limited companies get a great tax break on money put into a pension.” So, I said, "Sure, it sounds good to me, if it means I'm not giving it to the government." I built up a pension reserve without even thinking about it. So, I'm okay. But not everybody's like that. Other people wanted to put their money up their nose or down the petrol tank of their large Rolls Royces or whatever they wanted to do. It's a free world. I think I probably knew even at the age of 21 that I wasn't going to sustain this for more than 40 years.

There's something about being hermetically sealed from the record company and/or the manager that I would recommend if it's possible to do. I always remained at arm's length. For a lot of people, it's not possible. They're not making enough money. But in my day, the manager was the man who said, "Why don't I take care of the bills, Bill? All the payments. Just leave it all to me." Most musicians would leave everything to the manager, and of course it all went pear-shaped. On the whole, I've been self-guided and rather hermetically sealed from the seductive siren call of those who would wish to do it for me, which meant that on the whole I've probably received financially about as much as 80 percent of what I should have got, and that is astonishingly high in the music industry.

Some of your contemporaries perform on the oldies circuit and in package tours, wishing they could gracefully bow out like you did. Is there a cathartic element about not being caught in that trap?

I think you’re right about that. But I didn't have to do that. If I had done that, it would be because I wanted to. I didn't want to but I didn't have to. That kind of freedom I think is important. That means a lot to me. I was able to go to university without earning a dime for five years, stick my head in a library, and I thoroughly enjoyed that.

Websites:

Bill Bruford

Bill Bruford on Facebook