Donate to Innerviews

Since 1994, Innerviews has provided uncompromising, in-depth interviews with musicians across every genre imaginable. And it does that with no trackers, cookies, clickbait, or advertising.

Your donations are welcome to help continue its mission of highlighting incredible music and artists, without any commercial considerations.

Your contributions will be instantly transformed into stories and videos, and cover hosting and web management costs. Importantly, your dollars will help ensure Innerviews remains absolutely free to all visitors, independent of their ability to financially support it.

Please consider making a donation today by using the PayPal QR code below.

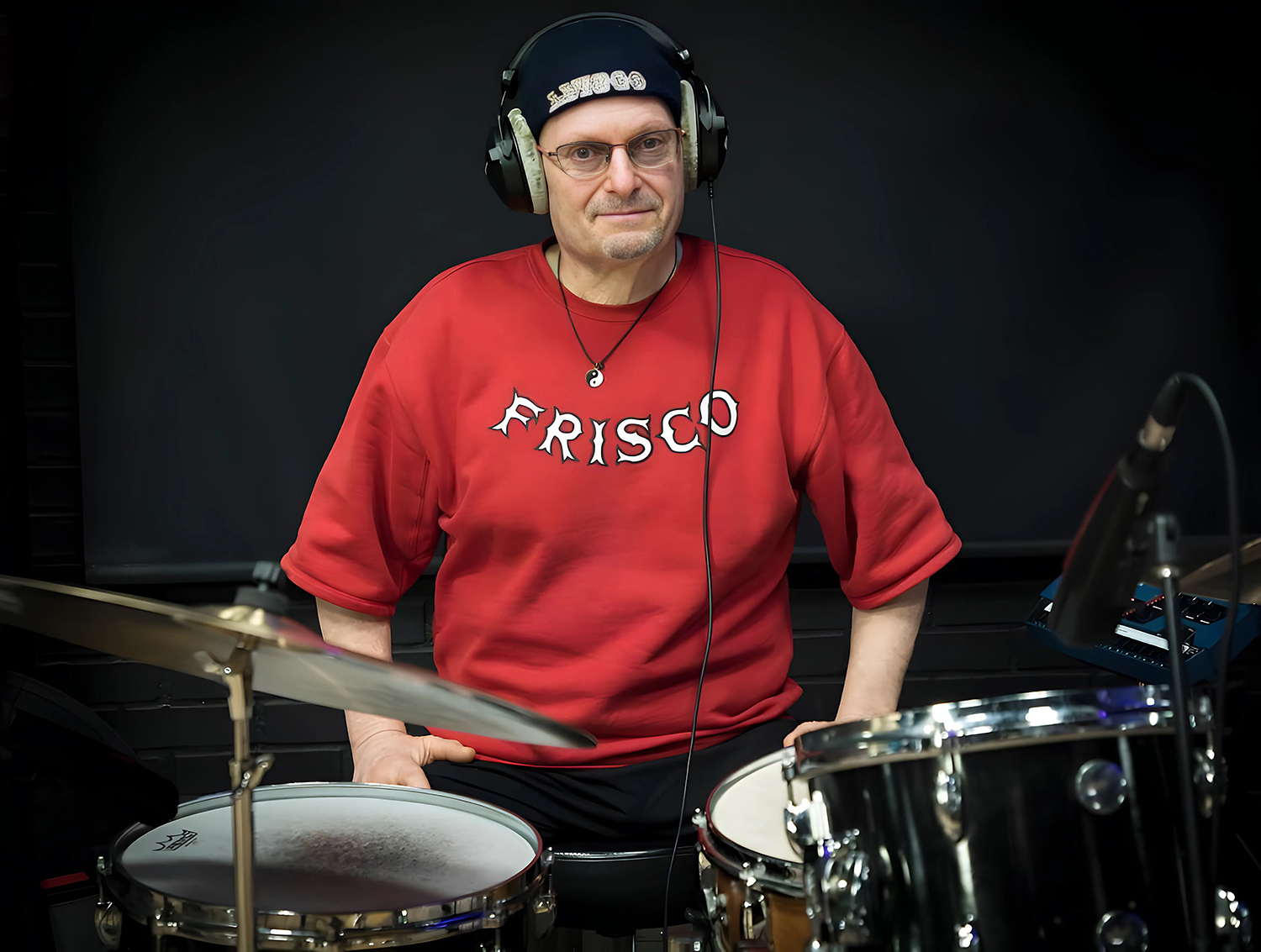

Brian Melvin

Finding Your Rhythm

by Anil Prasad

Copyright © 2024 Anil Prasad.

Photo: Brian Melvin Collection

Photo: Brian Melvin Collection

Brian Melvin is a free spirit. The drummer, percussionist, and composer focuses on creativity, exploration, and matters of the heart and soul, ahead of any political or music industry concerns. While he pays attention to the latter elements, he doesn’t let them define his life. Instead, he’s found his own bliss and continually recalibrates his performance and recording approach to make whatever circumstances that emerge work for him.

Melvin’s five-decade career is a testament to his philosophy. He was born in San Francisco and is now a resident of Tallinn, Estonia, when he isn’t traveling across the planet performing in jazz, rock, and world music ensembles.

He possesses a deft touch designed to mesh collaboratively with his bandmates. He’s categorically uninterested in overplaying or showboating. It’s why all-star musicians including Michael Brecker, Joe Henderson, Ryo Kawasaki, John Scofield, Mike Stern, and Toots Thielmans have sought him out for gigs and recordings.

Melvin hit the ground running as a leader with his first album, a self-titled jazz-rock effort by his band Night Food, in 1985. The group featured legendary bassist Jaco Pastorius, pianist Jon Davis, saxophonist Rick Smith, and guitarist Paul Mousavizadeh. The album garnered a lot of global buzz, with radio DJs, journalists, and listeners alike appreciating the telepathic chemistry the rhythm section enjoyed.

Pastorius and Melvin became close friends and remained so until the bassist’s death in 1987. Prior to Pastorius’ passing, Melvin had completed two further albums with him. A second eponymous Night Food album emerged on CBS in 1988 that added Merl Saunders and Bob Weir into the mix. And in 1990, Standards Zone, a trio recording with Pastorius and Davis was released. It was a major hit, remaining at number one in the US jazz charts for more than three months.

Melvin went on to establish two further bands: Beatle Jazz and Fog. The former explores jazz-based interpretations of music by The Beatles, in partnership with pianist Dave Kikoski. The group has made four albums to date. Notably, its third release, With A Little Help From Our Friends, included contributions from Richard Bona, Joe Lovano, Mike Stern, and Larry Grenadier.

Fog, based on a partnership with guitarist Brad Buethe, also has four records to its credit. The band has a two-pronged focus. It takes well-known pop and rock songs, including tunes by Peter Gabriel, Bob Marley, Simon and Garfunkel, and The Rolling Stones, and transforms them into jazz-oriented instrumentals. Fog also delves into jazz classics, offering creative versions of music by the likes of Miles Davis, Wayne Shorter, and Ralph Towner.

In addition to band work, Melvin has nine albums released under his own name, including his latest, Tranesformation. It’s a deep-groove organ trio record that delves into the music of John Coltrane. Featuring guitarist Søren Lee and keyboardist Mads Søndergaard, Tranesformation offers a collection of Coltrane originals, as well as some of the pop covers that brought the saxophonist global acclaim, such as “My Favorite Things” and “Summertime.” It’s an inventive and invigorating take on this classic material.

Innerviews met Melvin at the Golden Gate Bistro in Richmond, Calif. where he was performing with a trio including guitarist Todd Bugbee and keyboardist James Miller. The band played interpretations of Grateful Dead classics across a well-received three-hour set.

Though Melvin is committed to his life in Estonia, he remains a proud San Francisco native. He maintains a home there, in addition to routinely wearing a Frisco-emblazoned hat and vest during his performances, as he did on this day. He’s soft spoken, but possesses a quiet intensity that surfaces when talking about transcending dogma and negative influences, and adhering to positive perspectives.

Photo: Brian Melvin Collection

Photo: Brian Melvin Collection

Given the state of the world, what are your thoughts about the importance of the arts to elevate people?

I like what Lao Tsu said, which is “Those who know do not speak. Those who speak do not know.”

When you were a child, you probably didn’t pay attention to what was going on politically. You were just into what you were doing, whether it was music, sports, or friends. There could have been all kinds of heavy shit going on all around the world at the time, but you didn’t care about it. That’s a really good lesson because it’s not really a dark time. It’s just a time. People don’t understand history. There have been much darker times. But when a new problem comes around in the present moment, it feels very meaningful to us.

It is a difficult time, though. And just like everyone else, I have to always try and work through what’s happening. But I know the situation is temporary. I still feel very fortunate to wake up every day and get another chance to do what I do, when I know kids are being slaughtered all over the world and countries are getting blown up.

Those of us in the United States have had the benefit of watching a lot of things through the television. And you’ve got to be really careful to not let it take you in so much. I’m 65 and at this moment, America’s in one of the more serious times it has had to face in a long time.

A large group of Americans like Donald Trump. I don’t. I never liked him from the first time I saw the man on TV. I’m a very sensitive, karmic-focused guy. I never bought his rap or attitude. I think he killed America when he became president and he’s trying to do it again. So, that’s very dangerous. I hope he doesn’t win. I don’t think that will happen. I believe karma’s going to catch up with him. Karma will get all the people like him, eventually. It’s just the way things work. None of the bad guys last. They’re temporary. There’s no longevity. Even Vladimir Putin is going to fucking die. Who comes next, we don’t know. Trump? There’s no way he’s long for this world. Benjamin Netanyahu? I’ve always despised him and his turn’s coming, too. There’s a whole lot of karma coming down the pike as you and I speak in this present moment.

I’ve absorbed so much from traveling around the world and having been involved in music since I was five years old. I’m also heavily into martial arts and all kinds of Eastern philosophy. I’ve practiced Tai Chi for 40 years. I meditate and swim every day. It’s all about finding your rhythm and trying not to let anything take you outside of it. The political stuff can sometimes do that. I care about what happens, but one of the lessons is to not be too attached to a specific outcome.

I believe in collective consciousness. I believe in good. I also believe that there are troublemakers who want bad things to happen. And behind that negative energy is the same old story: greed, money, ignorance, selfishness, and huge egos. The other thing these guys all have in common is that they constantly lie. Everything Putin, Trump, and Netanyahu say is a lie. They’re all using the same playbook, which is spin things and lie, lie, lie. And then pretty soon most people will believe the lies. At least, that’s their thinking. Sure, some do believe the lies, but there’s a big majority that don’t.

I have a lot to be thankful for. I still love nature and just looking at the blue sky and clouds. I get to play music. I get to eat. I get to do this interview. I stay positive during all of it. There’s a concept in Zen Buddhism called shoshin which means “beginner’s mind” or “empty mind.” It’s about letting go of preconceptions and approaching everything from a place of openness. It’s also about trying to get to a place of emptiness, because everything comes from that place.

So many people long for the illusion that goes “I wish everything was peaceful and perfect.” But things have never been like that and never will be. It’s what keeps the belly of all spirituality hungry.

If you dive into deeper pockets of spirituality, you realize the goal is to just be. Can you just be without thinking you have to be? I’m also really into that as a drummer. I’ve been lucky to study and hang out with many masters. And now, I love giving back to people through music. I love playing. I love creating opportunities. I love creating positive experiences. It’s a blessing to be alive.

Brian Melvin and Elvin Jones, 1991 | Photo: Brian Melvin Collection

Brian Melvin and Elvin Jones, 1991 | Photo: Brian Melvin Collection

Describe your drive to explore the work of John Coltrane on Tranesformation, and the repertoire you chose to record.

John Coltrane is a guru for me. I was also good friends with Elvin Jones, who is another guru. We hung a lot when he came through San Francisco.

I’m always going back to Coltrane’s music. I’ve recorded a lot of his music over the years. This album emerged from me spending a lot of time in Denmark and playing with Søren Lee. He wanted to make a record. I said “I’ve always wanted to make an organ trio record. Let’s do one of Coltrane’s music.” He loved the idea. One thing led to another, and we made it happen.

It's a lovely record. I think it came out nice. It’s part of the cosmos and reflects listening to our inward and outward vibes.

As I mentioned, I do a lot of meditation and a lot of musical ideas come to me when I’m empty. I started sending Søren the names of tunes I thought of during meditation that I felt would be really good in an organ trio format and he liked them. He added a few he wanted to play. And then I said, “I think we should include ‘Summertime’ and ‘My Favorite Things’—some of the tunes Coltrane interpreted from popular music.”

A lot of people don’t realize Coltrane got very famous rearranging and reharmonizing these pop tunes. It brought him a bigger audience. I did something related with the group Beatle Jazz, together with Dave Kikoski. We recorded the most Beatle songs in the history of jazz—more than 40 of them.

We also have things like “Spiral,” “Cousin Mary,” and “Dahomey Dance” which aren’t as well known. Coltrane’s repertoire is so big that it’s a really deep thing to try to narrow it down for a record. The truth is, we were always thinking about something else that could be on there, but eventually you must surrender to the fact that “Hey, it’s got enough, now.”

Tranesformation includes a short drum solo titled “M-Elvin.” Tell me about its inclusion.

It’s my tip of the hat to Elvin. He and I always joked about the fact that his name’s Elvin and my last name’s Melvin. That’s why it’s “M-Elvin.” I think he would have liked this record. He and I were very, very close. He knew my love for the drums and blessed me when I was 18 at the Keystone Corner club in San Francisco.

One night in 1976, he kicked everybody out and said, “You stay.” I said, “Damn, what’s going on?” There was a little side door that went into a small room. He said, “Let’s go in there.” I said, “Okay.” He said, “Get on your knees.” And he put his hand on top of my head and said, “Wherever you go in the drum world, Elvin Jones will be with you.”

He knew my love for him when I played. It’s a vibe. Whenever Elvin came to San Francisco, I’d bring him things like African instruments. His wife Keiko would kick everybody else out and say “Melvin, you can stay.” The same thing happened with Buddy Rich, who I first met when I was eight. I also got to spend a lot of time with Art Blakey, Al Foster, Billy Higgins, Philly Joe Jones, Max Roach, Jerry Granelli, George Marsh, Eddie Marshall, Richard Goldberg, Scott Morris, and Donald Bailey.

I learned from all of them. I met them all when I was young. I was playing everywhere. They could see I wasn’t where they were yet, but they could also see I was coming up the ladder. So, they would feed me soulful information and befriend me. They knew I was in this for real and that I’m not a hobby guy. They understood I was going for it.

The Brian Melvin Quartet at Bird & Beckett, San Francisco, CA, November 2023: Søren Lee, Peter Barshay, Brian Melvin, and Danny Walsh | Photo: Anil Prasad

The Brian Melvin Quartet at Bird & Beckett, San Francisco, CA, November 2023: Søren Lee, Peter Barshay, Brian Melvin, and Danny Walsh | Photo: Anil Prasad

Søren Lee is a major collaborative presence for you. Talk about what makes him an ideal musical partner.

I first met Søren 40 years ago in Denmark. We initially played together when he was 18 or so. A lot of time went by, and I went back to Denmark, we met, talked, and said, “Let’s play again.”

I really like Søren as a person and guitarist. He’s capable of so much stuff. He’s another guy who did his homework and knows all the styles. We like a lot of the same music. But the most important thing is if you vibe and get along, which we do.

The music doesn’t usually come first. When people have a good vibe, that’s when the best music is played. It’s never a case of, “Oh, I’m going to hire him.” That’s just rolling the dice. If you have a true friendship and like the way they play, chances are you’ll make nice music, and that’s the case for us.

You just wrapped up a set of Grateful Dead music ahead of this interview. Tell me about your interest in interpreting and performing its music.

Everything started with the English rock and roll drummers when I was a young kid. I was a big fan of Charlie Watts, John Bonham, Mitch Mitchell, Ringo Starr, and Keith Moon. Then I got into the San Francisco stuff. I became friends with Bill Kreutzmann, Mickey Hart, and knew all the guys from Santana.

Mickey and Bill had something really special. They practiced a lot, kept elevating, and grew and grew. They were never satisfied with where they were at. They came from a psychedelic jazz background, but Bill also had shuffle jazz and R&B experience, and Mickey was a world music champion who really loved Latin music. When a little LSD was dripped on Bill and Mickey, they morphed into a psychedelic octopus of drumming with constant deep improvisation.

I was also friends with Jerry Garcia, who is another one of my gurus. I think he’s one of the greatest musicians, ever. He even influenced my idea of how to drum. It’s so evident today, how he left behind this thing for people to grab onto forever. The Grateful Dead is a big, deep ocean of music, with incredible lyrics by Robert Hunter. It has imagery, mythology, and improvisation. It explores so many cultures. There’s so much they embodied.

By the time I got into my twenties, I went off into the jazz world, but I remained friends with them from a distance. I also had Bob Weir play on my 1988 Nightfood album with Jaco Pastorius. He’s on two tracks. Jeff Chimenti, who’s been with the Dead organization for more than 20 years, has also played with me.

Brian Melvin at Golden Gate Bistro, Richmond, CA, March 2024 | Photo: Anil Prasad

Brian Melvin at Golden Gate Bistro, Richmond, CA, March 2024 | Photo: Anil Prasad

Explore what you sought to capture on your previous album from 2022, Sound Color.

You’ll hear some ECM kind of stuff on it. Having lived in Europe, I’ve always been attracted to the Nordic sound. I love how it reflects nature and space.

The album’s title comes from how Elvin Jones used to talk about seeing colors when you play. He used to say he saw a lot of purple and gold. So, it’s sound color. I liked the way that sounded.

I also love avant-garde art by people like Wassily Kandinsky, Paul Klee, Gustave Moreau, and Joan Miró. When I look at their art, I’ll also hear music. In fact, Klee wrote a book called Painting Music in which he assigns a color to each note on the piano. Kandinsky’s book On the Spiritual in Art also resonated with me. He said concerts of the future will involve walking into a place, smelling aromas, seeing lights, and having every sense invoked. It almost sounds like a Grateful Dead concert.

I think Indian music also reflects what Kandinsky was talking about. The ragas and the times of day you play them, the emotions, and the colors are all part of that. Indian music involves a deep ocean of thought. The Dead were very influenced by Indian music, and Zakir Hussain even lived with Mickey Hart, and worked with him a lot.

I was very lucky to study with Zakir and his father Alla Rakha. I took my first lesson with both of them during the summer of 1976. Alla Rakha may be the greatest percussionist of all time. I get shivers down my spine just thinking about him. He spent his summers in San Francisco. So, I got to hang out with him a few times. Then, I’d run into him when I visited India. I remain friends with Zakir. He’s known me right from age 14 through now at age 65. I can’t do what they do. But they can’t do what I do, so there’s mutual respect.

For some reason, Alla Rakha really dug me, perhaps because I was a street guy. I’d bring him half-pints of booze because he’d like to nip on them. [laughs]

Why did you choose to relocate from the US to Tallinn, Estonia?

It’s something that just sort of happened. After growing up in San Francisco, I moved to New York City in the 1980s. I started out playing with Mike Stern in his trio there. We were friends through Jaco Pastorius. Jaco would grab the bass and sit in with Mike at the 55 Bar. Eventually, Mike started asking me to sit in and I turned into a regular. After that, I played with Dave Kikoski. I then met a great sax player named Danny Walsh, who I still work with.

One day, Danny calls me up and said, “Hey Brian, a lady from Estonia has a jazz festival she wants me to play at. Do you want to be part of my band?” So, I went, and it was cool. I met a lady there, one thing led to another, and I moved there in 2000. We had a daughter and later separated. I met another Estonian lady after that and had another daughter. We also separated. Then I met someone else in Estonia, and she and I have been together for eight years, and it has been great. So, all my girlfriends for the last 22 years have been Estonian.

Although I live in Estonia, I’m always traveling the world playing. I also still have my house in San Francisco. My niece Tiffany Melvin has a venue in the San Francisco Bay Area called The Brisbane Inn, and I help book that for her. She’s got a big heart and does a great job. So, I still have a deep connection to the area.

Your first major public splash was with your Night Food and Standards Zone albums with Jaco Pastorius. Describe how the opportunity to work with him emerged.

Todd Barkan, who ran the Keystone Corner in San Francisco, was living in Holland during the mid-‘80s. It was a tough period for him. He had lost everything and went to work for Timeless Records there. I would hang out with Todd, and I helped him find a place to live once. He said, “I think I can get you a record deal with Timeless. Do you want to make an album?” I said yes and then he told me “I know every musician in the world. Pick one and I’ll get them for your record.” I said, “Jaco.”

I flew back to San Francisco, and I get a call at 2am one night. I was living at my mom’s place at the time. She yells at me and says “Brian, who the fuck’s this guy calling so late? He says his name is Jaco.” I ran to the phone, and he said, “Is this Brian Melvin?” I said, “Yeah.” Then he goes, “This is Jaco Pastorius, the world’s greatest bass player. I hear you’re making a record. Do you want a bass player?” [laughs] Of course, I said yes. Then he said, “Put me on a plane right now.” So, I went to my mom and said, “I need your credit card. I gotta get this guy on my record. I’ll explain it to you later.”

Jaco missed his first plane from Florida. I had to get him another ticket. He made the second flight. He showed up at my house with no bass. He just had a little bag with his sandals in it, and the book Frankenstein.

Jaco got along really well with my mom. They became very close. My father had just passed away, so Jaco stayed in his room for three days. He’d just chill and read the Bible. He then came out of the room and said, “I’m done. Let’s hit. I’m ready.” We proceeded to play and then record what became the 1985 Night Food LP. We did a follow-up record in New York City for CBS called Nightfood, which included Bob Weir and Merl Saunders.

I also did a trio album with Jaco called Standards Zone, which was one of his favorite records that he made. It was something he always wanted to do. He loved standards, as did his dad, who was a singer. Standards Zone came out a few years after Jaco died in 1987. It went to number one for 13 weeks on the jazz charts back in 1990. I remember the radio guy at the label calling me up to let me know, but I wasn’t really into worrying about that. I was busy partying and gambling. It was all about vice. But looking back at it, that’s pretty deep.

Brian Melvin and Jaco Pastorius in concert, 1985 | Photo: Brian Melvin Collection

Brian Melvin and Jaco Pastorius in concert, 1985 | Photo: Brian Melvin Collection

Writers and musicians have differing opinions on Pastorius’ performances during the latter years of his life. What’s your view as someone that worked with him more than anyone during the mid-to-late ‘80s?

I feel Jaco was at his apex on my records. Peter Erskine even called me once and said, “I heard Standards Zone with you and Jaco and it’s brilliant.” So, I don’t have the negative experiences other people say they had. If you caught Jaco on an off night performing when he was drunk, that was maybe 5-10 percent of the time.

I’ve read stories some writers have put out there about Jaco, but you know what? None of these people were there. They never really hung with the cats. They got their stories from the outside.

Most people don’t know I got Jaco out of the psychiatric ward of Bellevue Hospital to live with me in 1986. He called me once from there, after being stuck there for eight weeks, and I said to him, “Man, you don’t belong in that place.” He’d say, “Get me out of here.” I said, “I’ll get you out.”

I’m more into natural therapy. They were giving him all these heavy fucking depression and anxiety medications that were turning him into a zombie. He said, “I ain’t taking this shit anymore.” I said, “I don’t blame you, man.”

One thing led to another after that. He was supposed to come and live with me in San Francisco again for a while, but then he ended up back in Florida during 1987. One night in September that year, Santana was playing a gig and Jaco tried to sneak onstage, and was thrown out. Then he went to a club in Wilton Manors near Fort Lauderdale. When Jaco was drinking, he could have a pretty foul mouth. As everyone knows, the manager of that club beat him up, leading to his death. Everybody knew sooner or later it wouldn’t be surprising if we got the news that Jaco was no longer with us.

Some musicians claim to have worked with the “good Jaco” instead of the “bad Jaco” towards the end of his life. I disagree with that. Jaco and I were brothers, not just musicians who hung out. We’d play basketball, get high, and go to the beach. We were real friends. When I was with him, it was about tapping into the light, not the dark.

Saying there was a “bad Jaco,” is like saying Bird or Coltrane were only good at the beginning and not at the end of their lives. Like Bird and Coltrane, Jaco had a gift from God. These guys all knew the streets. They knew drugs. But they were always contributing. Everyone loved Jaco. That includes Wayne Shorter, Herbie Hancock, Joe Zawinul, and Joni Mitchell. None of them judged Jaco by a few incidents in his life.

There were ups and downs working with Jaco, and nothing lasts forever. But I look back at my time with him very fondly. I thank God that I had the chance to be his friend and play music with that genius. We made history together and some beautiful records. So, thanks Jaco.

You once said “I’m playing my life story” when making music. Elaborate on that.

I’m so lucky that I get to do what I do. It’s a blessing. I wouldn’t exchange my life for anybody else’s. My experiences are mine. When you see me on the bandstand, you’re seeing me bring my life into what I do. That’s it. Nobody else’s.

There are challenges being a musician these days. But I’ve had to stand on my own two feet in many different circumstances, and I’m okay, and still doing it. If you’re not part of the problem, be part of the solution. I’m always trying to figure out what the next step is. Too many people expect a silver fucking spoon. That’s one of the problems. We’re all here improvising through this thing called life.

Wayne Shorter once said, “Music’s a drop in the ocean of my life.” That’s the reality. I’ve got kids. I work on my health. I’ve got relationships. I’ve got bills—you know, all the things everyone has. So, music is an ornament on the tree. It ain’t the tree. The tree is the spirit world and that’s where I exist.