Donate to Innerviews

Since 1994, Innerviews has provided uncompromising, in-depth interviews with musicians across every genre imaginable. And it does that with no trackers, cookies, clickbait, or advertising.

Your donations are welcome to help continue its mission of highlighting incredible music and artists, without any commercial considerations.

Your contributions will be instantly transformed into stories and videos, and cover hosting and web management costs. Importantly, your dollars will help ensure Innerviews remains absolutely free to all visitors, independent of their ability to financially support it.

Please consider making a donation today by using the PayPal QR code below.

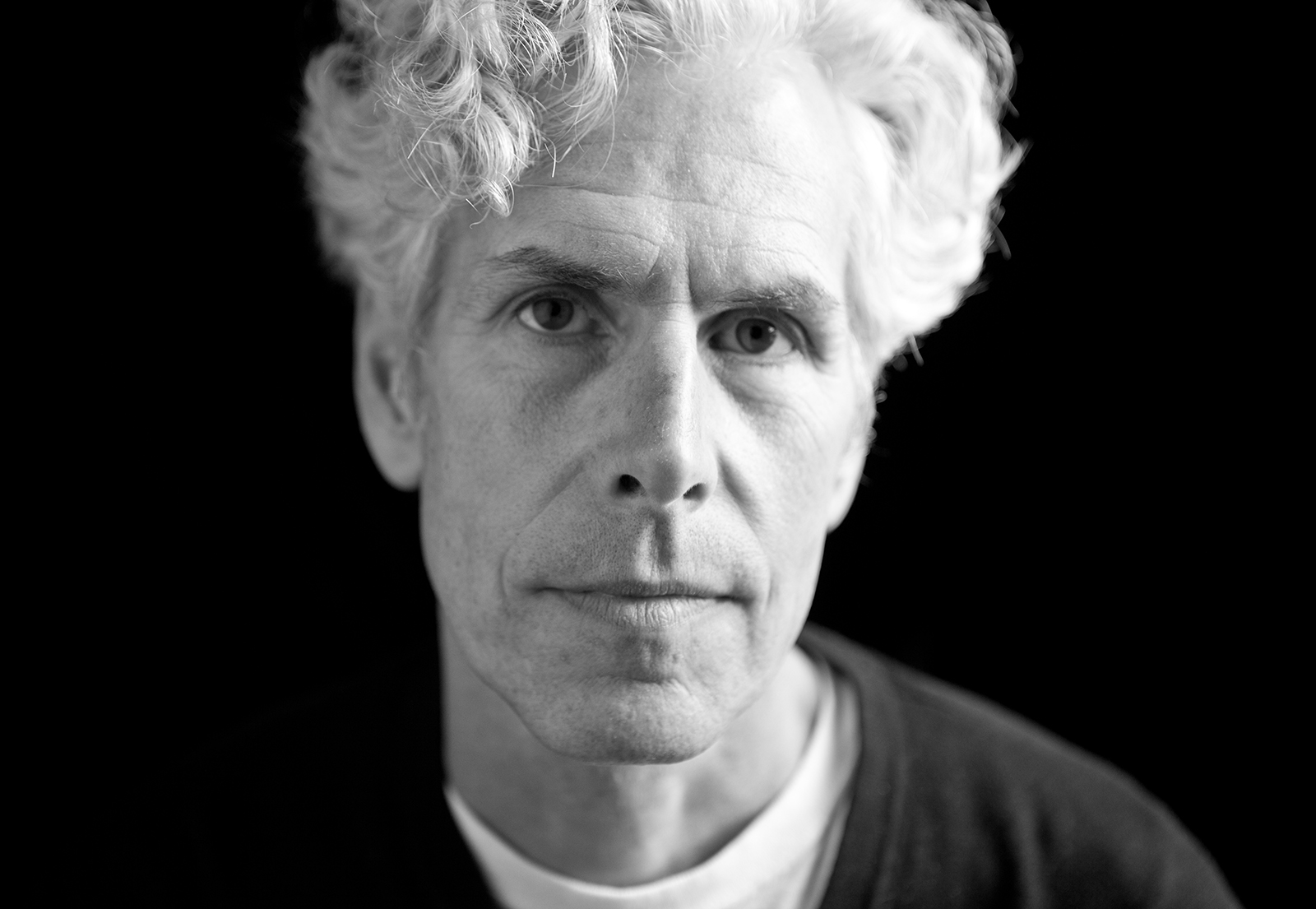

Rob Fetters

Practicing Life

by Anil Prasad

Copyright © 2024 Anil Prasad.

Photo: Michael Wilson

Photo: Michael Wilson

Rob Fetters is a one-man music industry. While many artists agonize over the myriad uncertainties in the business, the Cincinnati-based singer-songwriter, guitarist, and producer has chosen to dispose of those concerns and go 100-percent DIY.

He records, produces, and releases his own albums full of smart, tightly-constructed rock and pop, infused with incredibly creative arrangements. He books house concerts across America. And he helms an ongoing series of YouTube-streamed gigs called Fetters Is Cheap! with more than 65 performances to date.

In every context, Fetters’ listeners support him by purchasing recordings, hosting concerts, arranging ticket sales to friends and family, and donating to support the YouTube livestreams. It’s a direct relationship that’s paid dividends both in terms of liberation from industry dependence and connecting with fans at the most open-minded and open-hearted level.

Fetters has a long and storied history of prior music business engagements. He co-founded The Raisins, one of most popular rock acts to emerge from the US Midwest. From 1975-1985, the band’s profile expanded significantly across the region, consistently selling out clubs and theaters during the height of its popularity. It created a devoted multi-generational audience that still holds the band dear more than 40 year after breaking up. The group performs three very rare reunion shows in Cincinnati in March 2024 to celebrate its legacy.

The Raisins, with lineups including bassist Bob Nyswonger, keyboardists Ricky Nye and Tom Toth, and drummers Bam Powell and Chris Arduser, were courted by major labels, including Clive Davis at Arista Records. But negotiations never worked out, and the band operated at the indie level throughout its existence.

The Raisins' lone self-titled, revered studio album from 1983 was produced by Adrian Belew. After the band dissolved in 1985, Fetters, Arduser, and Nyswonger joined forces with Belew to form a new group called The Bears. The sophisticated pop quartet combined new songs with classic Raisins tracks. It recorded two albums for the I.R.S. Records subsidiary Primitive Man Recording Company, before splitting up in 1989. The band minus Belew went on as Psychodots, making five albums and working as a live unit from 1991-2018.

The Bears reemerged in 1997 to record three more albums. While it never announced an official breakup, the death of Arduser in 2023 after a long health struggle makes further activity unlikely.

Fetters’ focus is now squarely on his own output. He just released Mother, his fifth solo disc. It’s a diverse album of guitar-based pop with an existential bent. It examines facing the complexity of adult life head on, including overcoming career, family, and relationship struggles, as well as the difficulty of helplessly watching friends travel down destructive paths.

Mother includes contributions from Raisins bandmates Nyswonger and Powell, bassist Matt Malley, and vocalists Alice Peacock and Belinda Lipscomb. It’s also a family affair, with Fetters’ son Noah playing drums, his wife Susan on vocal harmonies, his mother Patricia providing artwork, and his other son Sam doing layout.

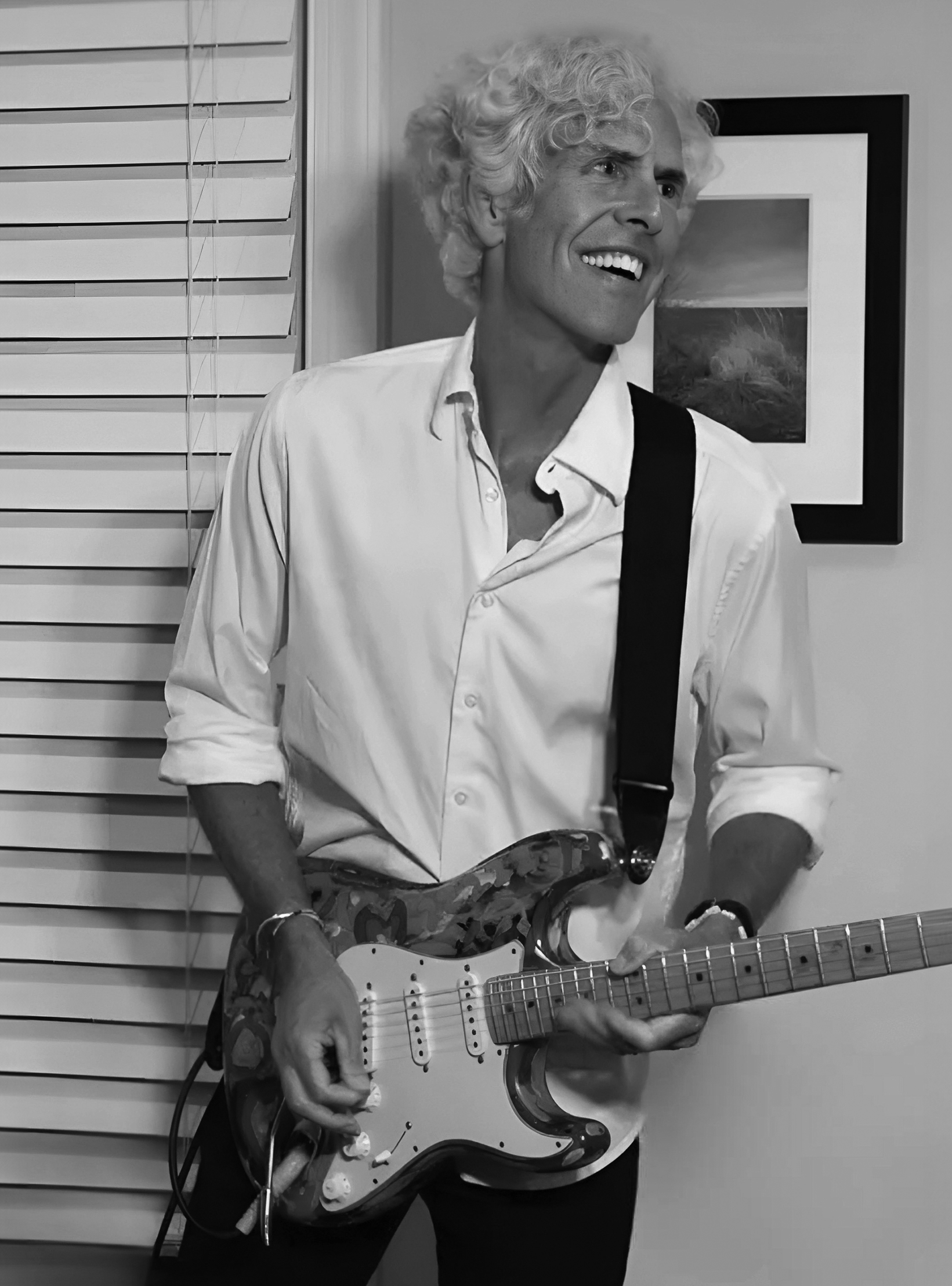

Rob Fetters at his home studio in Cincinnati, Ohio | Photo: Michael Wilson

Rob Fetters at his home studio in Cincinnati, Ohio | Photo: Michael Wilson

You’ve been focusing on house concerts and livestreams as your core performance avenues. Describe how those approaches came together and your interest in pursuing them.

What happened in late 2018 is Psychodots stopped playing and I was without a band. So, some friends convinced me to try to play a house concert. I had been to a couple of house concerts where people played stripped-down versions of their work, with acoustic guitar, and maybe a tiny little living room PA. I thought that was interesting for three or four songs, but wouldn’t sustain a whole evening.

I decided to remix backing tracks from my records and play live to them, to audiences of 25-30 people. The dynamics can be fabulous with a really nice Bose system that I have. Basically, I’m delivering my studio experience into the living room of fans, and it sounds really good. Acoustics are generally really good around a lot of furniture. Sound isn't bouncing off the walls.

I’d say I’m playing as well as I can in these contexts. I’m singing and playing like it’s a first take in the studio. It’s like, “Okay, I’ve got the tracks ready. Now, it’s time to sing and play, and I only get one shot to get it right.” That’s how I think. It raised the stakes and intensity to a level I had not experienced before and was really satisfying. I felt like the quality of the experience was really good for me. I know for sure it was really good for the audiences because they generally flipped out. If I would play a sad song, they would be crying, and if I played a goofy song, they'd be laughing. If I did a little bit of stunt guitar work, they'd be standing up screaming.

I remember back when I was part of Adrian Belew’s Inner Revolution tour. Everyone would talk about wanting the big hit, as we’d travel across North America. But the manager once said, “Think small” in a kind of snarky way. Now, I feel like they were really missing something. It’s in these small environments where real magic can happen. Of course, that can happen in a large room full of people, when you’re rocking and rolling with a good band. But what I hadn’t thought about is that it can happen in another way, too.

The really cool thing with music happens when I’m at the very beginning of writing a song. I’ll have an idea and things start to come together. Maybe I have a verse and chorus. As those ideas keep coming, I get really excited. People can get all mystical about it and call it the muse or whatever, but it feels magical and miraculous to me. And then comes the work—the craft stage, as Rick Rubin might say. Finishing the song is the hard part. You have to record it and face all the problems and solutions that entails. I found that playing songs to a small crowd provides a feeling very close to that.

When I do these shows, I find the songs seem to have a deeper meaning. People are with me. I don’t have to explain everything to them, and I can really enjoy the experience.

I was planning on going on a house concert tour in California, after doing the Pacific Northwest and Eastern Seaboard, and there were people in Texas and Arizona that were interested, too. But then the pandemic happened. My son Noah, who helps me in the studio, convinced me to give livestreams a shot. So, what I did is play the same sort of house concert, but in a haphazard ‘80s public access cable TV kind of way. [laughs] I’ve done dozens of them now. Originally, I thought I’d just do a few.

The truth is, at the beginning, I didn’t want to do them at all. I thought I was going to fuck up, sing out of tune, and miss notes. I didn’t want to do that on a livestream and get busted for it, but it turned out to be okay. I also found people really connected to them and loved them. I still get letters from people that say, “Hey, you really helped me during the pandemic. It was something to look forward to every Saturday night.”

Another thing that really turned on for me was the freedom of not being in a band and having to play the same songs every night. That’s not necessarily a bad thing, because you can get to different levels of performance. But you can also turn into a zombie when you play the same song 500 times in a row. With these shows, I have a pool of say 100 songs I can move around from week to week, so it’s always really fresh for me. Sometimes, I play requests from fans who want the better-known ones, but I always get to play my more obscure songs as well. So, it was really satisfying from that point of view.

As far as engagement goes, I don’t worry about having many thousands of viewers. I focus on the hundreds. I think there are probably 2,500 people in the world that are paying attention to me, and there are a few hundred who are really paying attention and communicating back. And that’s enough for me. I’m a believer in the less I need, the better I feel.

Photo: Timmy Samuel

Photo: Timmy Samuel

What have these experiences taught you about the art of self-reliance?

The music industry for me has always been a bad, rough business fraught with problems. Today, I would never tell anybody to get in the music business to make money.

My main story is that I've been able to switch gears and put on different hats along the way. I never said, “I want to learn how to be a recording engineer.” But I always wanted to work with really good recording engineers, and I eventually I learned how to do it myself. I somehow acquired a really good work ethic because of my involvement with other musicians and other super-talented people.

I’ve seen across my life that not everybody has a really good work ethic and that can cause problems. Some people just can't see projects through to the end. And somehow, I learned how to do that. I don't think I learned it in the music business. I think I learned it from my high school journalism teacher.

Once, I had been out in the parking lot during lunch smoking pot with my friends. I had a feature that I hadn't turned into him. He said, “Where's the story?” I said, “I haven't started it yet.” He was very upset and stuck his finger in my chest. He'd probably get in trouble for doing that now, but I've been grateful to him forever. He then said, “Do you know what a deadline means? A deadline means you're dead if you miss the deadline.” So, I got busy, and I wrote my feature. It was a review of The Kinks' Muswell Hillbillies record. It was a positive review for the high school paper, and it established for me that there’s a certain timeframe to get something done.

Talk about the core experiences that inspired Mother.

Some of the songs had been written for my prior record Ship Shake, but due to just the group depression of the pandemic, I didn't want to have too many dark songs on that record.

Most of the songs for Mother were written when my wife and I lived in Brooklyn for a year-and-a-half between 2022-2023. We had an apartment there and were helping with our first granddaughter so her parents could go to work. They’re both educators. It was such a great experience taking care of a baby learning to walk and talk, and to coach and protect her.

I’m a Cincinnati, Ohio person. I had visited New York many times, but I was always working during those trips. It was always about a gig and staying in a hotel. There was a specific purpose. But to live in Brooklyn and be around the diversity of humanity, including people from so many other countries speaking languages I don’t know was amazing. As far as skin color goes, I would often be in the minority, and I loved it. Also, I enjoy solitude, but in Brooklyn you don’t get that. And yes, it’s dangerous and hard to live there. It’s very expensive.

All of that gave me inspiration to write the album. The energy in Brooklyn is palpable with people hustling and working until they’re dog tired, and then burning up that money really fast. There’s a fire in everybody that’s in New York, and that includes people who are immigrants that are barely making it. Everybody seems to be working to survive.

When I had moments alone with a Telecaster—with no twang bar or amplifier—songs just started popping out. It came from all that activity. Also, the fact that I was doing a lot of work that is traditionally culturally delegated to women, like changing diapers, was another point of inspiration. It’s a good feeling to do these physical actions, and it’s exhausting work.

Is that why you named the album Mother?

I didn't know what else to call the album. It's the nicest name I think I could call a record. I thought a lot about my mom during that time. I was getting my ass kicked by a two-year old baby girl. [laughs] And my relationship with my wife is great, wonderful, deep, and long lasting. But we were in tight quarters. Our apartment was small. We're used to a four-bedroom house in Cincinnati. It was a strain on a relationship. And I learned a few things—things I knew, but I actualized them more.

There was also the fact that in Brooklyn, if I needed to get out, it was easy for me at 9pm or 10pm to go out and go for a run in Prospect Park. Women can't do that. They are not afforded those liberties like a white male like me is without even thinking. It's a different thing for my wife, who also exercises a lot and walks. What happened is my respect and love for women got deeper. Half the songs on the record are about that and about me dealing with it. I still have a lot to learn about how I can best support the women in my life.

Let’s explore a few tracks from Mother, starting with “Brothermother.”

In one of our previous interviews, I said I’m a Christian. I'm a Christian in the sense that I think there's Christian philosophy that I think holds true for me. The idea of not doing to people anything that you wouldn't want done to you is important to me. But I'm an agnostic at best. I practice life.

In my education as a human, which is ongoing, when things have been really dark in my life, and maybe not so dark, I will pray.

I'm a recovery person. I'm in a couple of 12-step groups and have been for 34 years. I'm a sober person. I know that it's a really good idea if I don't drink. And I'm happy to say I haven't had a drink in all those years. But part of the program is praying and meditating. And my sponsor said praying is a really good thing, especially if you do it out loud. When you do, you can hear yourself. So, I do that. It's just kind of a way of laying out a blueprint. “Brothermother” is simply, for me, a conversation through prayer.

The song also has to do with the fact that my mom died 32 years ago. But a lot of times, I still have mental conversations with her.

The song title “Embarrassed” has a dual meaning. Tell me about it.

It’s talking about a relationship that has gone bad, but I don’t want to blame the other person. I also didn’t want to blame myself. And I wanted to say that out loud. But then the chorus says I don’t want anyone to hear what I have to say.

Honestly, 10 days before the record went to mastering, I thought about leaving the song off. It seemed like if I had written a song that I didn’t want anyone to hear, it was hypocritical to go ahead and let people hear it.

So, I’m full of fear about putting out some of the songs I’ve written. But I also think that if I don’t put them out, I’m a traitor to the cause. I feel I’ve got to write these songs. I need to go all the goddamn way with what matters. Good writing goes to some really dark and weird places sometimes.

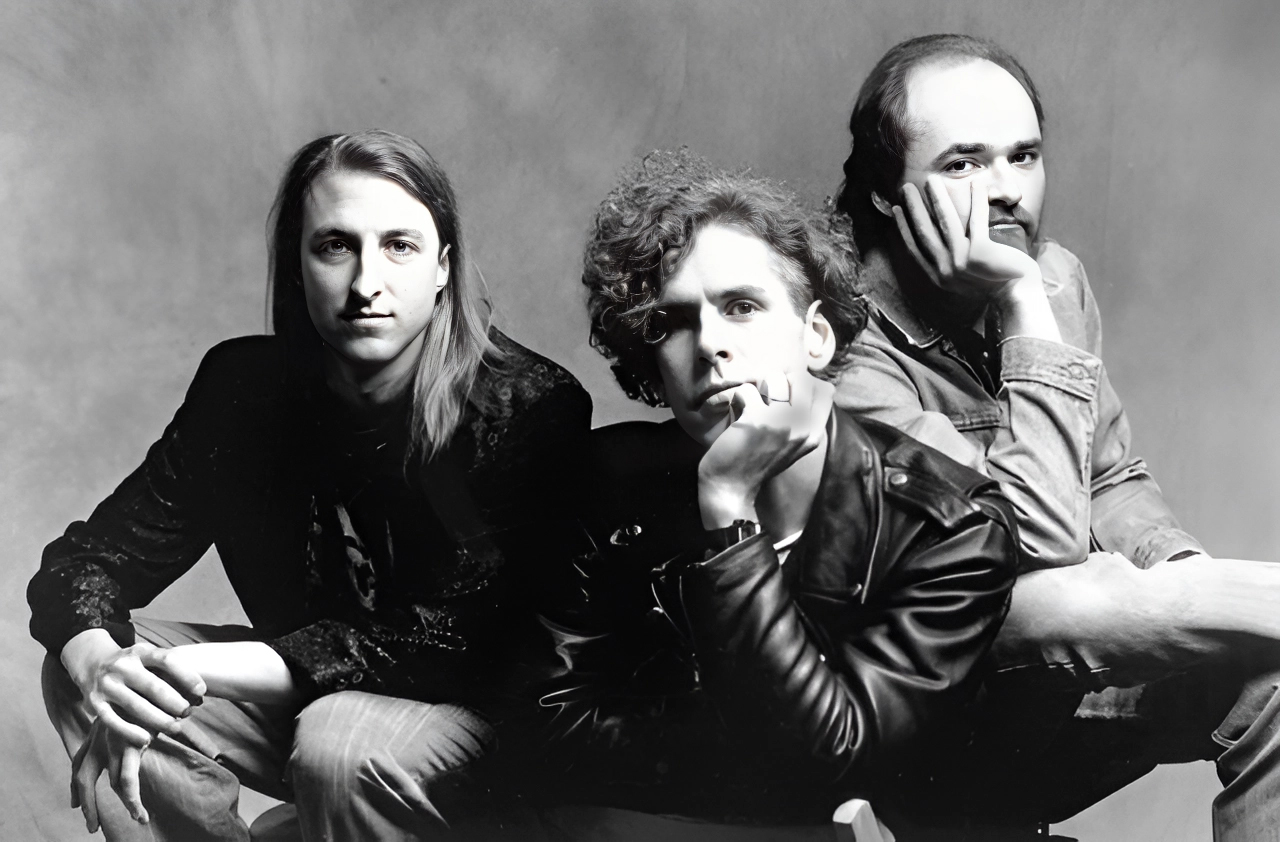

Psychodots, 1989: Chris Arduser, Rob Fetters, and Bob Nyswonger | Photo: Michael Wilson

Psychodots, 1989: Chris Arduser, Rob Fetters, and Bob Nyswonger | Photo: Michael Wilson

“Lamento” explores Chris Arduser’s difficult journey through life and the factors that contributed to his tragic departure last year. Reflect on the song and Arduser’s passing.

I wrote it a year-and-a-half ago in Brooklyn. I had written several letters to Chris that I didn’t send. It’s a good habit to get your thoughts down. I’m so glad I didn’t send them. But “Lamento” is a letter I did send.

I didn’t know Chris was going to die, but you don’t have to be a prophet with my experience with Alcohol Use Disorder to know what happens if you’ve got it and got it bad. If it’s chronic and progressive, it can be fatal.

I was close enough to Chris to see what was happening to him and it was heartbreaking. For a couple of years, I had dreams with Chris in them weekly and it was affecting me in a really fundamental way. I watched someone who was really bright, wonderful, creative, fun, and a challenging compatriot, and saw him lose everything. He was a person I was so delighted to play with. His musical abilities were wonderful, and I learned so much from him. To have it all taken away by a horrible addiction is not a moral failure. We really tried everything we could do to help him, but apparently, there was nothing we could do about it. Chris had a really bad case of Alcohol Use Disorder.

Chris was a really beautiful person, but the disease took everything away. It happened in a kind of a slow, insidious way. It was taking things away from him before we even knew there was an issue, because he was such a professional. And then it got to a point where, despite his professionalism, he couldn't do those things any longer. There were so many people that worked with him, and one by one, they started understanding what was happening.

The day he died, someone said, within hours, “We can say it was his heart. We don’t have to say he drank himself to death.” That was a real wake-up call for me that people don’t want to talk about this shit. And yet, it’s the only reason I’m here, talking to you today. If I hadn’t had people around me who actually named what it was I was going through, I would have drunk myself to death. I needed help. I needed to be around other people who were trying not to drink.

Once drinking is embedded in you, it’s really hard to stop. It’s the hardest thing I’ve ever done. I’ve had my heart broken as many times as anyone else has, but the hardest thing I’ve ever done is simply not drink. It was harder than the 29 marathons I’ve run since I quit. It took a long time to get rid of the craving. And I’m still working on it. When things get really bleak, I have to remember “I could make this situation a lot worse by having a drink.”

At age 35, I managed to stop doing something that was killing me, and I was rewarded completely. I got a second chance. That’s a really happy thing. And there are millions of people like me.

We lost Chris sooner than we should have, but that’s not his whole story. It’s just what killed him. Chris’ work and friendship live on.

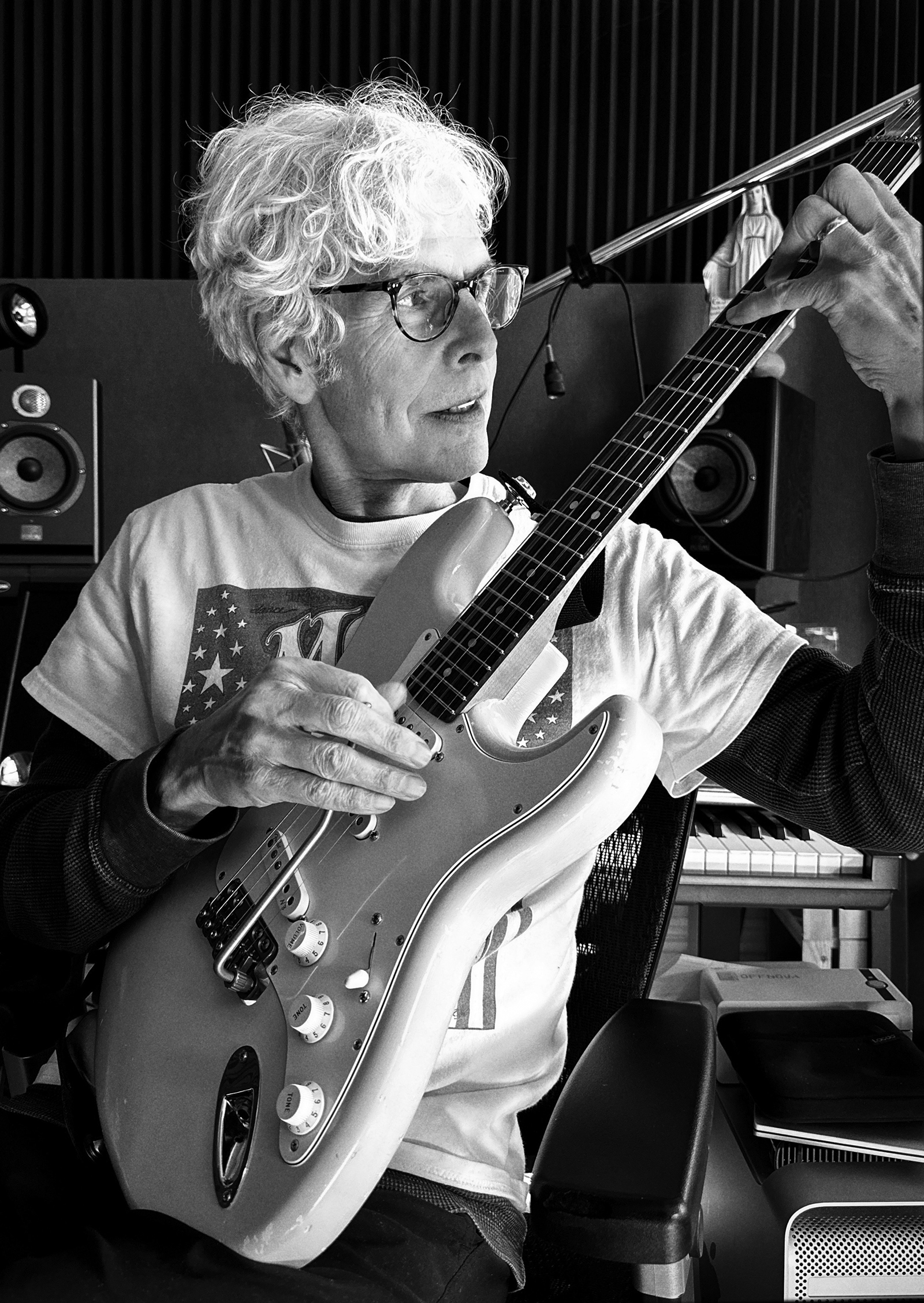

Photo: Emily Russo

Photo: Emily Russo

Mother showcases a wide variety of arrangements. Discuss your drive to keep infusing new approaches into what you do.

I worry about repeating myself—not that repeating oneself is a bad thing. I’ve had really good music teachers. I think my gig working at Sound Images also really helped. That was my commercial job for 10 years as a paid servant for an advertising agency. The work was all over the place. One day it might be “We’re going to do Queen’s ‘We Will Rock You.’” The next it might be doing something that sounds like George Gershwin or Carl Stalling.

Being in an environment where any kind of request could come through the door was a valuable experience. And if I didn’t know how to do something, I knew who to call. Cincinnati is a big metropolitan area with a lot of great musicians across every genre from gospel to classical.

So, in the last 10 years or so, I’ve been able to go in lots of different directions without being afraid. For instance, Mother has some keyboard stuff on it that I played myself. Originally, I thought I’d get my friend Steve Schmidt, a fabulous jazz player, to play on it. But then I realized I was just playing like he would play anyway. I can fake things well enough on keyboard, a couple of measures at a time, and make it work. But I can’t get through a whole song on keyboards the same way I can on guitar.

To me, Mother feels like it’s asking big questions about life and the nature of existence. Your previous album, Ship Shake from 2020, feels more like a motivational record about getting on with things and making the best of your circumstances. The track “Turn This Ship Around” from Ship Shake seems particularly emblematic in that regard.

It’s kind of a rock anthem about positivity and fighting through stuff. I wrote that in 2009 and was embarrassed by its gung-ho approach. I wrote it for myself because I was having trouble, financially. I had four kids. Everything was going wrong. I had a one-year non-compete agreement after the Sound Images gig where I wrote commercials. And then a bunch of stuff fell through I thought I was going to be doing.

So, this song was me telling me to buck myself up. I think I got that from my maternal grandparents and their stories about staying afloat during the Great Depression. My experience is that if I don’t stop working, the situation improves. You’ve got to just keep hammering away at something good and usually things will happen. Sometimes I don’t have to hammer hard. I just have to show up and hammer and I’ll see a positive difference.

“Can’t Take It Back” from Ship Shake offers some decent advice for modern Western society that’s so reliant on social media.

Yeah. A whole lot of good could happen if people would just stop talking once in a while. Go make some tea. Throw a blanket on that homeless person. Quit fighting.

The Zen master Huang Po once famously said “Open mouth already a mistake.” [laughs] I just ran with that as an idea. The fact is, that idea speaks to probably any time it’s said. It just makes sense.

Ship Shake’s “Dog is God” is one of your most mercurial tracks with some wild sound design. It also advocates pursuing one’s own spiritual vision. Provide some insight into the song.

I wrote that six or seven years ago when Psychodots were still playing. We did that one live. I stole the music from a gig I did for Xbox. The music was originally in an Xbox commercial for a little while. It’s one of the few songs on that album that I made some money with. I’m sure I took the money and just went into the recording studio and hired musicians with it.

As for the song’s lyrics, what can I say? Let’s start a new church and go all the way with what goddamn matters. Keep it simple stupid. It’s true. How’s that? [laughs] I had my friends speak lines in the song and I used them in a bit of musique concrète. There’s probably enough in there to get me in trouble with most organized religions.

What made you want to revisit the classic Raisins track “Artichoke” on Ship Shake?

I wrote it during the last year The Raisins were still playing in 1985. It was referencing a girl I still cared about, but things didn’t work out. There’s a recording of it on The Raisins’ Everything and More compilation. Psychodots also recorded it on our first album from 1991. It was okay but felt a little stiff.

When I started doing house concerts, I wanted to play it. So, Bob Nyswonger and Bam Powell, who were both in The Raisins, came over for a recording session and we rerecorded some Raisins tracks so I could play them at those gigs. The new version felt better and swung. We didn’t overthink it. As I played it at house concerts, I felt “Whoa. This is the right tempo and feel.” So, it was a natural progression to finish the recording and put it on the record and leave that girl alone. She’s doing fine, by the way.

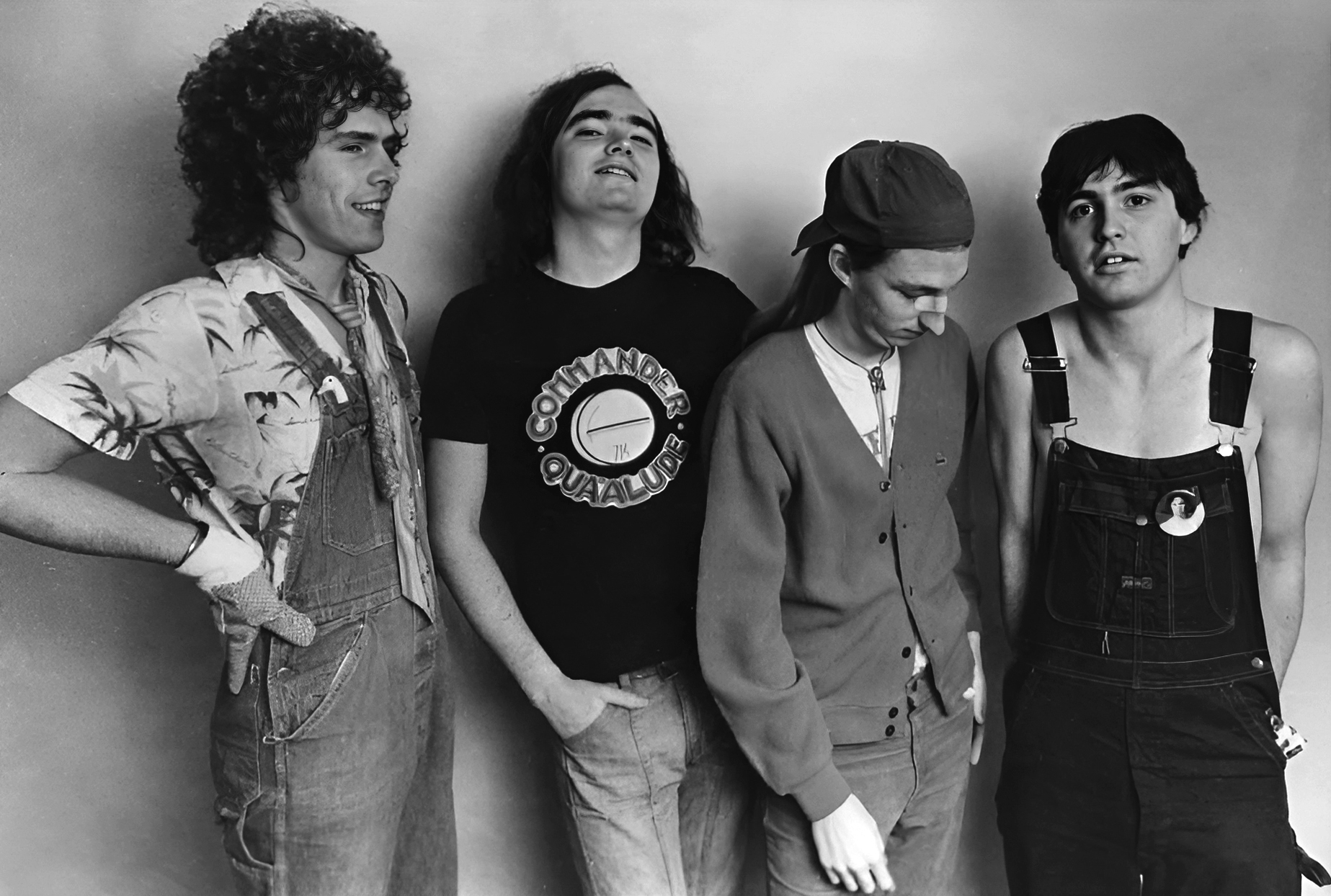

The Raisins, 1977 | Rob Fetters, Bob Nyswonger, Chris Arduser, and Tom Toth | Photo: Stan Hertzman

The Raisins, 1977 | Rob Fetters, Bob Nyswonger, Chris Arduser, and Tom Toth | Photo: Stan Hertzman

The Raisins are reforming to play three gigs in March in Cincinnati. Tell me about the impetus for the reunion and what people can expect.

What happened is there was a band called Not The Raisins with Tim Miller, Rick Mosher, and Bob Mitchell, who are old Raisins fans who play in the Cambridge, Massachusetts area. They’re all business professionals, and for fun, they play old Raisins songs and record them as well. They do a great job.

Those guys contacted Ricky Nye and I last year and said “Hey, we want you to play. We’ll pay you a fee and you can promote the show any way you want, but find a charity of your choice and give the ticket money away." It sounded like a wonderful idea, and we decided to do it.

We chose to give half the money to The Freestore Foodbank, which is a place you can get food and clothes if you’re needy. The other half goes to Play it Forward, which collects money and distributes it to musicians that need money for medical expenses.

The original offer was to just play one night. We thought “No, because if we screw up whatever song, we want a second chance.” So, we wanted two nights, and we went from there. And then it became three shows.

It has been really complicated getting the business parts of this together. We also wanted to play in a great venue. The most fun Raisins gigs were the ones where there were about 25 people there at a little club somewhere, and there wasn’t even a real stage. We’d just play and that’s where the band got smoking hot. The more successful we got, the more we had to learn how to play concert stages.

We chose The Woodward Theater in Cincinnati. It’s a really nice venue. Psychodots have played there. It has a really good-sounding PA. The people who run the club are members of the Cincinnati music family. They’re people we trust.

The first two shows sold out in five hours. And the third one sold out within a day. We’re really happy about that. It’s humbling and really gratifying to know all the work we did means so much to so many people around here. We were the local band that didn’t get really famous nationwide, but we were really famous where we were.

You turn 70 in September. What does that milestone mean for you?

About a year ago, I thought I was going to stop or at least slow things down. But I talked to other people who are still working as they get older—not necessarily artists—and they do it because they like what they do.

Going back to my mom, if she was still here, she would say “Keep doing it until you can’t do it.” I have enough support from people who can keep me going. I knew I was never going to get rich making music. I knew I needed to invest some money and be frugal and sock away some cash or I’ll be miserable, poor, and sick. But as long as I have supporters, the show will go on.

With Fetters Is Cheap!, patrons send in money and keep it going. And it means the other people who play on the tracks or shows can get little checks after every season. The rule is, if I can come out $100 ahead, so it’s not a hobby, it’s very legit for me to do it. From a business point of view, that’s about as far into the music business as I want to go.

I’ve been working non-stop since July 2023. The final recordings and mixing work on Mother went for two-and-a half months and I got that out. From there, I went directly into doing house concerts during the fall, and then went into doing Fetters Is Cheap! That seems like it’s just 75 minutes on a Saturday night, but the pre-production work on each one starts 12 hours after the last broadcast.

I also still practice a lot. I run through those songs over and over again, and tweak sound a lot. I’ll still walk into the studio and pick up a guitar and play just because I want to. It just feels good. I’m always willing to help friends with recording projects. It’s really satisfying.

My grandparents saw me out in California once when I was playing with The Bears. Things looked good from the outside. People thought I was making money with that band. We wish we were making money, but we weren’t. But like my mom, my grandparents would say “You’re happy. You love what you do. Keep at it.” And they both knew what it was like to work and not like what they do. So, I should honor that and keep going forward.