Donate to Innerviews

Since 1994, Innerviews has provided uncompromising, in-depth interviews with musicians across every genre imaginable. And it does that with no trackers, cookies, clickbait, or advertising.

Your donations are welcome to help continue its mission of highlighting incredible music and artists, without any commercial considerations.

Your contributions will be instantly transformed into stories and videos, and cover hosting and web management costs. Importantly, your dollars will help ensure Innerviews remains absolutely free to all visitors, independent of their ability to financially support it.

Please consider making a donation today by using the PayPal QR code below.

Field Music

The Stories Write Stories

by Anil Prasad

Copyright © 2020 Anil Prasad. All rights reserved.

Field Music: Peter Brewis and David Brewis | Photo: Andy Martin

Field Music: Peter Brewis and David Brewis | Photo: Andy Martin

Simply put, Field Music is responsible for some of the most uncompromising and inventive rock and pop made today. Since forming in 2004, the duo, comprised of brothers David and Peter Brewis, is resolutely determined to create meaningful songs with arrangements full of fascinating, thrilling twists. The siblings, based in Sunderland, England, are both impressive multi-instrumentalists that collaborate on each other’s songs in Field Music and across several related bands and projects.

Making a New World, the group’s seventh and latest album, is its most ambitious to date. The recording explores the First World War’s dramatic impact on the Western world and beyond, long after it ended on November 11, 1918. The brothers dug deep below the surface to uncover important stories that inspired their muse. Making a New World includes songs about the war’s influence on reparations, public housing, women’s health, gender reassignment surgery, air traffic control, and modern art movements. The pieces are nuanced, detailed and a testament to the brothers’ knack for taking complex subject matter and making it both entertaining and melodically memorable.

There’s an inherent political perspective in Making a New World, along with other Field Music and solo output. They express displeasure with the world’s turn towards right-wing parties and policies, xenophobia, misogyny, and racism. In fact, David’s most recent solo release, 2019’s 45, his third album under the name School of Language, focuses specifically on the Trump administration. It sets the president’s own fatuous dialog to music, as well as perspectives from his cabinet mates and political foes. It’s a funk-and-soul-infused recording with a heavy dose of sarcasm and wit.

You Tell Me, Peter’s duo with vocalist and flautist Sarah Hayes, also released a new album in 2019. The self-titled effort examines the art of communication within the complexities of modern society at the micro and macro levels. It’s a beautifully-crafted effort with layered compositions, lush arrangements, strings, and minimalist percussion.

Field Music is entirely a DIY effort. The brothers have built up a studio and live performance infrastructure that enables them to achieve their aims without outside financing. From the start, they’ve understood the difficulties of the music industry, particularly for musicians unwilling to yield to commercial pressure. The duo represents its own self-sustaining ecosystem that supports itself and their families, as well as an extended team of Field Music-related musicians and collaborators. It’s a model of efficiency that’s inspiring many to pursue a similar path.

Innerviews spoke to David and Peter extensively about the history of Field Music, their key solo projects and the value and challenges of keeping things in-house.

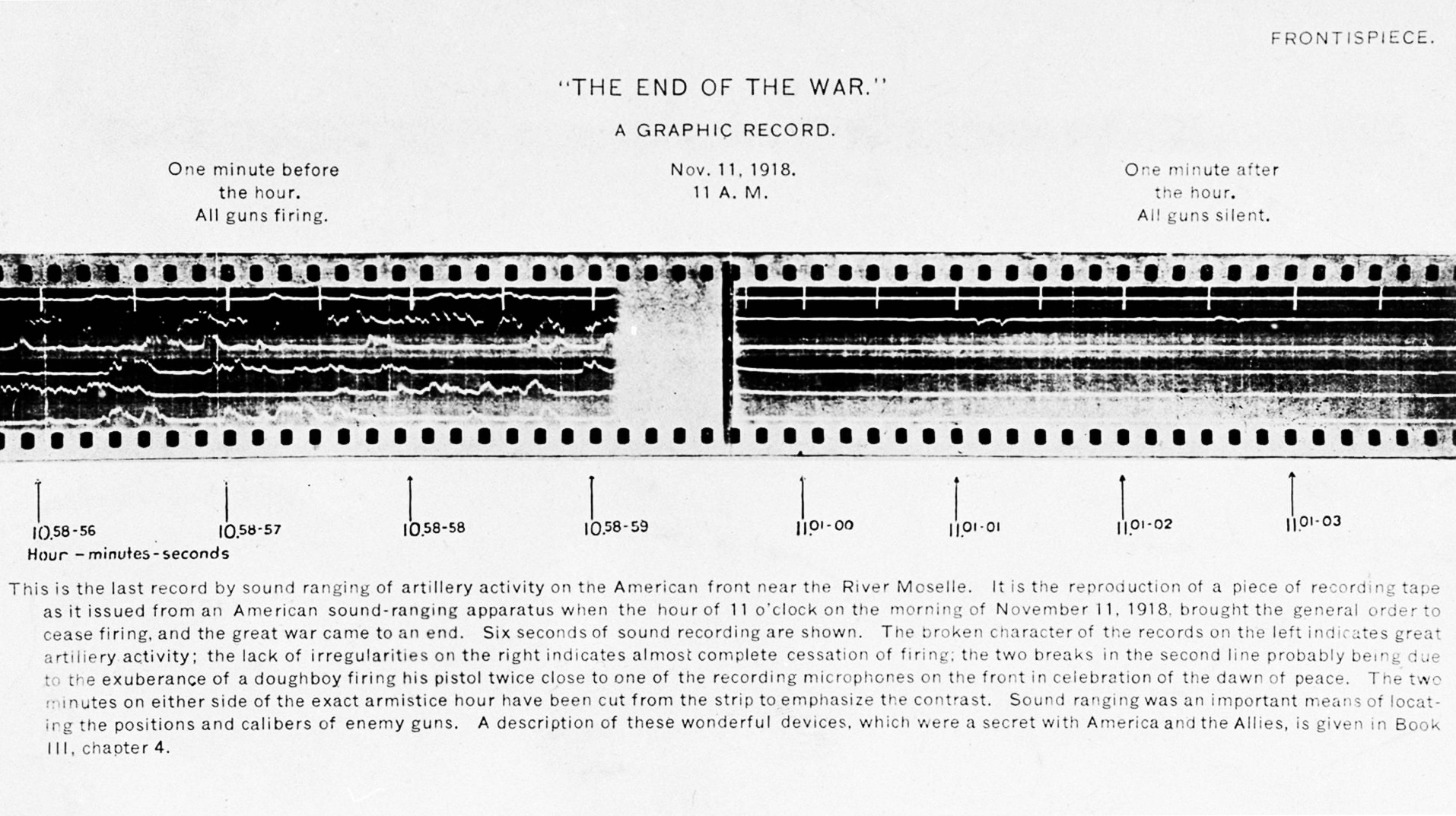

The sound ranging image of the end of the First World War | Photo: Imperial War Museum

The sound ranging image of the end of the First World War | Photo: Imperial War Museum

David Brewis

Describe the origins of Making a New World.

We were approached by the Imperial War Museum in London to do two performances as part of a season of events they had called Making a New World in 2018. It all grew out of a sound ranging image, which literally captured the sound of the final minute of the First World War. The image showed six lines going across a piece of film. It represented six microphones set up behind the frontline. The mics were actually oil cans wired to a machine which could record vibrations. The distances between the vibrations could be plotted on a chart so they could pinpoint where enemy guns were.

We imagined those lines going out across the next hundred years, because it was initially done as part of the armistice centenary commemorations. We tried to think of things from the war where the vibrations had carried on across all of that time. We did a bit of research and found stories we thought we could write about. Initially, we thought the project would be mostly instrumental. But because of the stories, we ended up writing a lot of songs with wide-ranging subject matter.

We've done commissions before, but we've never had a commission that turned into an album of songs. I think that was a bit of a surprise to us, but it seemed a shame for it just to be those two performances inside museums in Manchester and London. We wanted to expand on that.

You’ve said you made the album by accident. How so?

We didn't set out to make an album. We set out to make this performance piece about the First World War. We were just putting together a performance. We usually write songs and then me and Peter record them. Next, we bring the songs to the band to make sense of them to play live. This was one where we were writing songs to perform and at some point quite late in that process, we thought we should record this properly, and it could turn into an album. That's why it feels like an accidental record to us.

Tell me about the creative process behind the recording and how it differed from previous Field Music albums.

It differed mostly in that the arrangements weren’t finalized before we brought them to the band, because we didn't have time. Kev Dosdale, who plays guitar in the band, was also going to do the visuals. We had an impromptu meeting on a ferry coming back from Ireland after a festival where we talked about how we might structure it in order to make the visuals work, but at this point we hadn't prepared anything. That was the beginning of September 2018. Then me and Peter just started collecting all of our little musical ideas. We’ve never struggled to come up with lots of musical ideas, so that was relatively easy.

Then we went on the Internet trying to find where we might start to find stories. That was really easy because if you go into a search engine and type "technology advancements, First World War," you automatically get a big list, and that leads you into things you can research further. I would say we were really riding on the hoof. All of the songs were finished by Christmas, and then we were into the last bits of arrangement and rehearsal. We finalized the visuals after Christmas. We also had to have our lyrics fact-checked by the museum. I’m glad they were, because I made a couple of mistakes on things historians would not be happy about.

In that period between the beginning of September and the middle of December, it was about frantically piecing together research and music and turning things into lyrics. A big change for me and Peter was that we weren't writing songs about ourselves. What we realized was that in order to write these kind of stories, we needed to decide who was telling the story. That's not often been something we've had to deal with in other Field Music songs because we don't have that many third-person narrative songs. Realizing who a story came from was the catalyst for these songs to make sense. That was quite different.

It was also strange to have rehearsals in which we didn't know what everybody was supposed to be playing beforehand. Usually, we have Andrew Lowther playing a bass part, Liz Corney playing a keyboard part and singing. Then we’d ask Kev to play all the other parts somehow. Typically, the process is interpreting a recording we’ve made that works for however many people are playing in the band, which is usually five musicians. This project was built a little more from scratch.

Field Music's live lineup: Peter Brewis, Kev Dosdale, David Brewis, Andrew Lowther, and Liz Corney | Photo: Andy Martin

Field Music's live lineup: Peter Brewis, Kev Dosdale, David Brewis, Andrew Lowther, and Liz Corney | Photo: Andy Martin

Was that a liberating shift for you?

Well, we didn’t have time to get bogged down in things. Everything happened so quickly and everyone was very accommodating. We’d rehearse something one day and the next day we’d think "Actually, the second guitar should do this, so the backing vocal line should do this." It might change again slightly after that.

Certainly, the process of writing songs from research was really liberating. Not being bound in subject matter and writing stories which don't usually get turned into songs, but finding a way to do it was very interesting. It made me feel like a proper songwriter.

Why would you ever feel like you aren’t a proper songwriter?

I do, all the time. I say that because of the cliché that goes "If it's a great song, you can just sit down and play it with an acoustic guitar." We don't have many songs like that. There's something about the classic approach to songwriting, which maybe points to me and Peter as being more producers than songwriters. Whereas, this project made us feel "Oh, we can write songs about anything. We can do it really fast as well.” Sometimes it feels like it takes us a long time to write songs even though our output has been fairly big.

A lot of Field Music output has very intricate arrangements and dynamic rhythm shifts. Does infusing songs with that level of ornamentation come naturally to you?

That is our natural way of doing things. I think it partly comes from the fact that we’re not wedded to a particular instrument. Very early on in the process of writing songs, we've usually got an idea of what the guitar will do, what the bass will do and the kind of rhythm the drums will play. Finding other things to put on top of a recording is never difficult. Knowing what we should leave out or when we should use particular ideas is where there's a little bit more of a conscious editing process.

There's a point in our musical growth where we started to notice the little things that have been put into songs, which made them more interesting. It's a thread that goes through so much of the music we like, from the most obvious things like the way The Beatles recorded all the way to how Led Zeppelin's albums are constructed. We also absolutely loved The Black Crowes' third album, Amorica. We’d pore over all the details of these albums to understand things like the little intricacies in the guitar parts or the way a bass line moved against the guitar parts. We’re just really absorbed by all of that.

As for how we deal with rhythm, let’s say the first part of a song is a guitar riff. We then think “How are the other instruments going to support it? Are you going to play against it? Are you going to try and pull it one way or another? Will you mix those things?”

With most guitar music certainly, the bass and drums always play a supporting role. But when we first started, on the first record more than anything, we had a philosophy in which the bass and drums will never support and they will always play against or push things one way or another. Then we realized this is a very impractical way to make music and is not very effective. But there are moments when bass and drums support the main riff, and then after 16 bars they’re pulling things in one direction or another. We also view the drums as something which are playing to the singing as much as the other instruments are.

Early on, a lot of the album reviews would always mention odd time signatures. To a certain extent, we hadn’t realized we were doing odd time signatures. Certainly, we haven't written them consciously to be that. It was just that we were following the vocal melody and everything went towards that rather than a chord progression. Usually, people write the lyrics on the top and you play the instruments according to the chord progression. We wrote riffs and a vocal melody, and everything else had to weave around those things. I'm not sure that counts as a philosophy, but I feel like that sums up most of our approach to it.

It took us a long time before we would let ourselves do something really straight on the drums. We realized that we can, but we don't do it all the time. So, we can use it in a way that makes things leap out when we want them to.

Photo: Ian West

Photo: Ian West

Both of you are multi-instrumentalists. How do you determine who plays what on a particular recording?

It's mostly to do with practicality, and it changes from how we record to how we play live. For instance, quite often, each of us writes a song in which we know what the drums should be. On stage, I know that Peter will play the drums for it, but when we record it, I'll show Peter a guide guitar part or a guide piano part and I'll play the drums. We both have our strengths and weaknesses. Peter is a much more refined drummer than me and can really play the piano, even though he will say that he can't.

I'm a more confident bass player. If you want the drums to thrash around a bit, that's where I come into my own. Peter has a more skilled ability to pick on the guitar, whereas the super-dry kind of sharp Prince-influenced guitar is something that is my thing. So, it depends song to song. There are plenty of songs in the catalog in which Peter is basically playing everything or I'm playing everything, and maybe we've done backing vocals for each other. I think if we both sing on it, it'll sound like a Field Music song, and it kind of doesn't matter who plays what.

What's your take on what the modern world can still learn from the First World War?

I think the main thing we learned from doing the project was that consequences are long and complicated, and that ill-thought-out solutions lead to tragedy down the line. I don't think the modern world has learned that lesson, certainly not in foreign policy. That feels even bleaker now that the UK has given up on the consensus of European peace after the Second World War. That was a hard-won peace, and here we are throwing it away in a xenophobic temper tantrum.

I think we tried with the record not to be judgmental about things. We wanted to present information and throw ideas around, but obviously our political views certainly come through in that. Whether there's a lesson for the wider world, I don't know. I feel so despondent about the state of things at the moment. Leaders can make a huge difference. Those big decisions made by leaders have massive consequences. The way leaders after the First World War bickered over how Germany was going to be restructured and how much reparation debt they were going to have to pay set the tone back a long time ago in Europe, and not in a good way. I don't know whether there could have been a better solution, but certainly the one they came up with wasn't great.

Given the topic matter of the new Field Music and School of Language albums, what role do you feel musicians should have in an era like this?

I broadly feel that artists should be writing about what is uppermost in their minds, and I don't have a problem if what's uppermost in somebody's mind are the personal travails that they're going through. For a lot of this period, what has been uppermost in my mind is what’s going on in the outside world. I feel like I need to engage with it, even though I'm totally aware that I'm not going to change anyone's mind. I am mostly preaching to the converted, as disappointing as that is. If what Donald Trump does at the moment is embolden white supremacists, then artists can do tiny things which embolden people who want to fight racism and who believe in the sanctity of democracy beyond personal gain. Even if artists do that in a tiny way, it’s beneficial because it encourages people to keep going. There are plenty of people who feel this way about it. It’s a small, useful thing an artist can do. I'm not expecting any fans of Trump to hear the School of Language record and change their mind about him.

Let’s go through several songs from the new album and get your thoughts on them, starting with “Best Kept Garden.”

I was looking at the housing boom that happened after the First World War. There was a crusading housing minister in the government called Dr. Christopher Addison who in quite a patrician, very traditional conservative British way decided that one of the big problems that needed to be fixed was housing for the working class. He came up with a very detailed plan of what this housing should be in order to give some comforts to the working class and to soldiers coming back home, a sense of dignity in work and in life. It resonated for me because my parents grew up in a post-Second World War housing estate—one of the biggest in Europe.

Social housing is something I'm really interested in. I know a social geographer and I got in touch with her and said, "Can you tell me about any housing estates that were built as a result of this Addison Act?” She said “Oh yes. Wythenshawe in Manchester is huge and Becontree in London is another." One of the fascinating things I found out about Becontree is they knew they were going to be moving lots of people from slums in inner London out to this new suburb with all of these picture-postcard houses that have their own gardens.

The government didn't really trust people to be able to look after the gardens, given the cramped open urban housing they'd been in before. In order to try and encourage this, they set up these “Best-Kept Garden competitions.” I thought, "Okay, well this is kind of nice in a patrician, overbearing way," and there's a little detail that the first stage of judging was done by the local rent collectors. You might end up in one of these estates with one family hiding behind the sofa from the local rent collector while the family next door are proudly showing off their chrysanthemums blooming in their garden.

I thought that juxtaposition was so illustrative of the British class system. Once I had those little details, I wrote this song, imagining someone saying, "Thank goodness for Dr. Christopher Addison. He sorted this all out for us, and I'm really going to sort my garden out. That bastard rent collector, I'm going to wipe that smug smile off his face."

The Field Music band in the studio during the Making a New World sessions | Photo: Andy Martin

The Field Music band in the studio during the Making a New World sessions | Photo: Andy Martin

“A Shot to the Arm.”

That’s one of Peter's songs. He already had this song about a particular schoolyard game where they basically used to punch each other. Then he was reading up about an artist in the ‘70s called Chris Burden who had done a piece where he got his friend to shoot him in the arm, and the idea was that he was just going to have just a tiny graze—enough to show the horror of being shot as a response to how the media was presenting images coming back from Vietnam and how people were being desensitized to it.

Unfortunately, his friend really, really shot him through the arm, and it was a terrible disgusting mess. When the police came, they said it was just an accident, rather than saying it was a piece of art. I think for Peter, it was a way to tie together this idea of fighting as a game, which desensitizes us from how awful real violence is.

Sometimes, Peter gets a little musical concept in his head, and he has to somehow make it work. Quite often these concepts will be really bizarre. What he's doing on that song is using something called a mirror inversion. Whatever he's playing with his right hand, he has to do the exact mirror with the left hand, and it really takes you far outside of what the keys should be. Peter's got the skill of taking these obscure musical ideas and somehow turning them into something which sounds like a pop song. It's quite a tricky one to play. If we did a video looking down on the piano keys as Peter or Liz plays it, you’ll see this very neat symmetry that pulls out something that’s quite strange, musically.

“Money Is a Memory.”

I was surprised to see that the final debt repayment on First World War reparations that Germany owed to the US wasn't paid until 2010. Germany had to take out loans from the US because obviously their economy was obliterated. It was a huge part of Hitler's campaign to be elected that these reparations were unjust. It really crippled the German economy and caused terrible hardship. Then he stopped paying them and they didn't start paying this debt again until reunification.

Between 1989 and 2010, payments on this debt kicked off again, and this was definitely one of the ones where I had to think about who was telling the story. In the song, it's someone in the back room at the German Treasury whose job it is to fulfill this boring administrative task of making sure this debt repayment is paid. All of the stuff that's underlying this action tells the story of this huge chunk of horror of the 20th century. In a way, I wanted to make it seem like this mundane task leads this lowly admin assistant into a kind of reverie of how we owe each other things, how a monetary system works, and the paper trail that surrounds our decisions. The paper trail can last a lot longer than we do and may have all of these unforeseen consequences.

I thought it would just be entirely appropriate to make it a kind of slow funk stomper. I wanted people to sing along with it and get the idea that, yeah, this paper trail is telling the dark story of Europe in the 20th century.

“Only in a Man's World.”

One of the first things I saw when I was doing the research was this story about how Kimberly-Clark had developed a kind of material during the First World War, which they thought would be used for dressings. When the US ended the war, it was like, "Wait, we can sell this to the US military and make a profit on it." Then they found out that nurses were using it for sanitary hygiene. After the war, they redesigned it and it became Kotex, the first modern sanitary towel. Then I started to look at the rest of the history of the sanitary towel, and there almost is no more history.

The advertising around it has stayed almost the same. There’s a certain kind of sense of implied shame involving the unspoken nature of it, especially to men. Men aren't supposed to know about it. The song is written from a man's perspective. He’s saying "I don't know about this. As I find out about this, it seems really wrong." There was some controversy in the UK a little while ago about how sanitary towels were taxed more than things like razor blades. The full VAT tax was paid on sanitary towels, as if it's not a necessity for people’s health. Instead of trying to write a story about it, I felt like it was something I just needed to declaim. Why is this? How has this happened?

I realized, well it's happened because men have been in charge for so long. If you want an illustration of how strong patriarchy has been, it's that these products are taxed more and men don't know about it, and women don't talk about it. It’s still seen as something kind of shameful, even though all human life depends on it.

I wanted to drill this into people’s brains and make them dance to the song. [laughs] I was so embarrassed when I had to show my wife this song. I wondered "Am I allowed to do this? Is this terrible?" When we first performed it at the museum in Manchester, a couple of senior staff members came up to me afterwards and said, "Thank you so much for writing that song." I was like, "Okay. Phew. It was okay to write it," even though I'd basically written a disco song about sanitary towels. [laughs]

The other story associated with the song is that of the Indian inventor Arunachalam Muruganantham. He was trying to help his own family and women in rural India by inventing a machine for pressing sanitary pads where they were needed, rather than whatever makeshift things women were using because they didn’t have the access or money to buy Kotex. People were telling him “Stop doing this. It’s really embarrassing that you are doing this.” Somehow, he kept going and made a really beneficial change for women.

Photo: Andy Martin

Photo: Andy Martin

“Do You Read Me?”

This one didn't really have a factual basis for the lyrics. I was just imagining what it might feel like to be a pilot, doing this incredibly dangerous job and feeling conflicted about being tethered to the ground by a radio signal. On the one hand, it makes your job slightly less dangerous and more effective. On the other, you're mired in a conflict where there is no freedom, no clean air, no space away from people even for a minute, and so your time in flight is a kind of ecstatic release. That I chose to write that story from that perspective probably says a lot about how much I value time alone.

And then the relentless rhythm felt a little bit like a spluttering engine—propulsive and a bit threatening. At the end it all floats off into a reverie. It even made sense to me that it would segue into “From a Dream, Into My Arms,” as if mulling your own mortality would have you dreaming about birth too.

Describe the continuum that 2016’s Commontime and 2018’s Open Here represented for Field Music.

I think musically, we'd hit a bit of a groove where we had this range of things that we could do. The range was from the poppiest, most upfront stuff to things veering towards intricate chamber music. When we went from Commontime to Open Here, there was a sense that we were just going to push a little bit further again with how poppy and upfront things could be—lyrically, as well. We’ve been gradually becoming less abstract since the first record and getting better at writing good lyrics that do tell the whole story and aren't reliant on somebody having to just assume that it means something even if they don't know what it means.

Also, with Open Here, we thought “We're going to push even further with things that aren't driven by drums, with orchestral elements, horns, and flute that are more intrinsic to what the songs are.” It did mean the songs on Open Here were difficult to play live. We did quite a few shows with extra members in the band in order to represent it. Also, there are the changes reflected in what the world is going through from early 2016 to 2018, in which Trump is elected and the Brexit vote happens. There’s also the fact that our kids are starting to grow up. I have a daughter, so the nature of the song is about how being a dad changes you a bit. That’s in contrast to songs on Commontime about being a dad in which I’m like, "Oh my god, I really want to go to sleep." [laughs]

Things became more nuanced on Open Here. It musically felt like a kind of consolidation of all of the things we knew how to do. There were a few things where it's like this is the kind of music Field Music make and there are a few things where it feels like we're still pushing at the edges before we turn into Field Music clichés, which I think is an okay place to be.

How do you look back at 2015’s Music for Drifters soundtrack?

I think it’s one of the best-sounding records we've done. There's a joy in listening to it for me because of how we made it, which was me, Peter and Andy Moore, who was the original keyboard player in the band, and the person we learned to play music with at school. He had been in our very first pop-rock band back in 1993. After Tones of Town, he went back to having a real job. He had much more of a sensible life than me and Peter did, so this was a project where we could get him in and bring in minimal musical ideas, not the kind of fleshed-out demos we might typically make. Literally, we’d start with just a guitar riff, a bass riff or a little keyboard idea and make something out of it. We wrote and arranged it by playing together in a room, and it felt like, “Oh yeah, we're a good band.”

It's difficult for me to know how evocative it is of what’s in the film Drifters that we wrote it for, but it feels that way to me because it brings back the images of what I was watching on the screen as I was trying to play a particular thing. It felt loose and free and it's not as refined or clever as a lot of the stuff we've done.

Drifters was one of the very first documentaries made by John Grierson. It’s a silent film made in 1929. Grierson is credited with coining the term “documentary.” The film follows a herring fishing fleet across the Shetland Islands to the North Sea fishing grounds. We did it as a commission for the 2013 Berwick Film & Media Arts Festival. Berwick is a little town right on the England-Scotland border.

We don't usually get to rip when we’re making music because we’re usually piecing things together. The performance was much more a part of the process. There was nothing synchronized like playing to clicks when we scored it. We were doing it from visual cues on the screen. We were set up at either side of the stage looking up, feeling really seasick, because we’re right next to a 30-foot-high screen bobbing around on waves as we play. It was a super-enjoyable process.

What are the benefits and challenges of working so closely with your brother for so long?

The benefit is that we have such a shared musical background that we can communicate really quickly about things. We have the same reference points both in terms of the music we listen to, and also in the styles of playing that we have at our disposal. It means that if we do it right, we can find ways to encourage each other and move things along fairly quickly, which is always more enjoyable for me.

The challenge is that we spend so much time together. There have been periods where if gigs aren't well attended, the drives are long and if we've got other stuff going on in our personal lives, we may bicker with each other in the same way that most siblings probably do. Also, when you know you're going to be sharing a hotel room with someone that night and spending six hours in a van together the next day, there aren't many ways to escape it.

Mostly we manage to avoid all of that. One of the ways we avoid it is to give ourselves other projects to do. Even when we help each other out with the other’s projects or play in each other's bands, it avoids the most difficult thing, which is just making decisions together. That's probably the same for any band, regardless of whether there are siblings in it. Making joint decisions is tricky. Me and Peter can do it to a point with a certain amount of acquiescence here and there. It’s a case of "I'll let you do that because I trust you." But then there will come a point where it's like, "Right, now I'm going to go make a School of Language album, and maybe I'll ask you to play on it, but it's my thing and I'm going to make all the decisions."

Having that kind of escape valve is a useful, maybe essential way of getting over that extended proximity that we've put ourselves in. We used to share a house. We thought “After we've moved out of the parental home a few years down the line, you know what, we should get a house together and I'll live upstairs and you live downstairs and everything will be fine.” That was a terrible idea. [laughs]

Sea From Shore photo shoot, 2008 | Photo: Ian West

Sea From Shore photo shoot, 2008 | Photo: Ian West

Let’s explore the beginnings of School of Language and its first album Sea From Shore from 2008.

It was a really necessary thing for me to do. We'd made the first Field Music records in fairly quick succession. We started out in the music industry and found a lot of it really frustrating. We got a certain amount of traction with those records, but especially in the UK, we were being lumped in with a kind of indie guitar music, which we felt no affinity for whatsoever. I was still working a proper job through a lot of that time, so all of our gigs were organized around taking holidays here and there and really just wearing ourselves out. By the time we'd finished recording Tones of Town, I was certainly ready to take a break from it.

But it turned out that I couldn't take a break from writing songs. I had lots of ideas where I thought, "Well instead of having to make this work for the band, I can just do anything. It doesn't have to be something we can play. It doesn't even have to be playable. I can just try every idea that I've got. I want to make music which sounds nothing like British indie guitar music." I think I managed to make something that didn’t and I think that was good.

I met Bettina Richards who runs Thrill Jockey on a Field Music tour in the US in 2007. When I finished the record, I sent it to her and she seemed really excited about putting it out. She also wanted me to play there as School of Language, even though I didn’t have a band. In the Thrill Jockey way, she said, "Oh, I'll find you some musicians. You'll be fine."

The process of making Sea From Shore, putting it out in the US in a totally different way and working with other musicians was like stepping into another world. I had Doug McCombs from Tortoise on bass and Ryan Rapsys on drums from Euphone. I felt much more comfortable in this context than any notion of British indie guitar music.

It also set the tone for what we could do as Field Music and beyond, rather than being stuck being an indie band. I got to try loads of different things in the studio and then live because we did it as a three-piece. I thought to myself, "Oh, I'm going to get better at the guitar, singing and I'm going to have to somehow make this work." It was just a really interesting stretch for myself.

What was your day job during this period?

I worked in the finance office for Oxfam. My main roles were paying the bills for 700 charity shops up and down the UK. I did math at university and later down the line, I learned how to use spreadsheets. That's always the backup option for me. I'm good at math. You can usually find some kind of job if you're good at math. Although when I first finished university and didn't have any job experience, I'd go for a lot of interviews where they'd say, "You know, you'll find this boring. You’ve got a first-class math degree." I was like, "Well maybe, but I don't have any other experience and I will be able to do your job.” I was being written off. It was probably a good thing I fell into music.

Sea From Shore features a four-part epic called “Rockist” full of intrigue and negative space. Provide some insight into creating it.

I was really toying with the idea of writing lines of lyrics and then chopping off the last word or the last two words. I wanted there to be lyrical space in it. As a hangover from Tones of Town, I was writing a lot of things in which I didn't want to use too many notes at a time. I wanted to be able to imply all of the harmony by only playing like two notes. All of those riffs are a bass only ever playing two notes at a time, rather than telling the harmonic story with strummed chords.

I constructed quite a few of the tracks on that record from samples of me dropping items in the bath and in a sink. It was the first record I'd made on a computer actually, using Logic Express. The first two Field Music albums were made on a hard disk recorder, so it was still a digital process, but they didn't have any of the kind of editing capabilities you have on a computer. Sea From Shore was the first time I could do things like that—sample all of these things and rearrange them and turn them backwards. We had a sampler earlier with Field Music, but it was so involved to make it work that it tended to put us off.

With the School of Language record, I could just let go and it's like, “Okay, this is going to be based around the distorted sound of a toothbrush dropping in the bath.” “Rockist Part 2” very much came from just letting all of these elements have a little bit more space than would typically be afforded in a normal song.

I'm not sure where the idea for basing things around loops of mouth sounds came from. I liked the idea of having things flow together. I also liked the idea of having things which didn't sound like rock music until the final piece where I was definitely listening to “Sweet Emotion” by Aerosmith. It's like I turned this piece of music into a tribute to it. And then, of course, it goes totally elsewhere at the end.

I would never in a million years have made a connection between “Rockist” and “Sweet Emotion.”

[laughs] Play them side by side. There are a lot of similarities. There are lots of clever things in the backing vocals and percussion of “Sweet Emotion” where you think “Oh wow, it’s not a complicated bit of music, but it’s got musical depth, slightly beyond what you’re conscious of just listening on the surface.” So yeah, “Rockist Part 4” and “Sweet Emotion.” Two peas in a pod.

Photo: Andy Martin

Photo: Andy Martin

The 2019 School of Language album, 45, is an ultra-satirical skewering of Donald Trump, which includes setting his own words to music. Describe your interest in pursuing the project.

It came straight off the back of creating the songs for Making a New World, in which I'd written songs from research, imagined characters and found a really liberating way to write. Then I had this chunk of time in which I had less interesting tasks to do in the studio, including tidying up mixes. Peter was on tour on his own as well, during this period. So, I just started to come up with these ideas based on what was in my mind most of the time, which is the situation in American politics. The band joked about it in a van journey I think on the way back from one of the Making a New World gigs, in which we tossed around song titles.

They very quickly became actual songs when I set my mind to it. I've also had it in my mind for a really, really long time that I wanted to make a much straighter funk and soul record. That's the music I've listened to most. It’s the music I'm probably most obsessed with over the last four or five years, definitely, but it's always been an undercurrent. I had such a huge James Brown obsession period. I’m really fascinated by the use of rhythm on those classic records from 1965-1971.

I'm aware that I can't sing like James Brown and if I was going to make a really straight solo record, I don't have the kind of voice that could carry that off. I can play the drums in that style, I can play the guitar and the bass in that style, but I can't sing like that, so whatever I do with it still has to be my style of singing. Those elements coming together just made this record happen really fast. Again, it was a really liberating, fun experience.

It felt like I had to do it fast so it didn't get in the way of making the Field Music record, and also because events were moving so quickly. The news cycle has sped up so much in the past three years that it feels appropriate for it to be an off-the-cuff piece of reporting as much as anything. It was very much driven by deciding who was going to tell each story. There are only two songs which are from Donald Trump's point of view. There’s a song from Hillary Clinton’s perspective, as well as one representing Alexander Nix, the head of Cambridge Analytica, for instance. There’s also a song from an underling at the State Department singing about Trump’s approach. He thinks “We haven’t been blown up yet. Maybe he’s a genius. But what it he’s not? Where does that leave us?”

How do you pair a soul music approach with songs about someone who has no soul?

It felt like a really appropriate thing to do—creating my own homage to Black American music by writing an album about somebody who seems to hate Black culture or sees it as lesser than his idea of what White culture is. I thought “If I’m going to do this, I have to make it a love letter to Black American music.”

Honestly, when I heard you were doing the album, I was slightly squeamish. I thought…

“I’m not sure I want to listen to it,” right?

Yeah. Even though I totally supported the intent. But you pulled it off and it’s incredibly entertaining.

It's a totally understandable state to be in. I mean I suppose it's different here in the UK because I've got that physical distance from it. I might have struggled to write in the same way about the situation around Brexit. At least with this, I've got this distance from the situation that you don’t, being in the US. From this distance, I wanted to really pull at the absurdity of the situation and what he says. I’m reading the book Fear: Trump in the White House that Bob Woodward wrote. It all seems like plausible stuff. There's a lot in the book taken from deep background interviews off the record.

So, how you can you make music related to the account of one person's ego or one person's strange and warped take on the world? I wanted it to be funny. As awful as it is, I felt like poking holes in it with humor was a more appropriate way for me to deal with it than writing a thrash metal album about Trump.

Interestingly, I never use Trump’s name on the record. I tried to include different people’s points of view. I’ve tried to avoid it just being my opinions about him. I wanted to project ideas of what people around him might think as well. Like I said earlier, I know I’m preaching to the choir, but I’m trying to provide a little bit of light relief to people who are really, really sick, disheartened, and outraged by what Trump has done.

Photo: Andy Martin

Photo: Andy Martin

You recently said Trump’s success made you wonder if you had any understanding of people whatsoever. Elaborate on that.

In 2016, Trump had a 40 percent approval rating. And with Brexit pushed through, it made me realize that I live in a bubble. I deal with other people who mostly think like I do, but our opinions aren’t representative of the world at large. The Brexit discourse in the UK is based on pure fantasy. I genuinely struggle to understand how anyone can support that or Trump, but they clearly do. But I don’t want to get to the point where I just say "Everyone who supports Trump is stupid.” There's the temptation to explain it that way, and even if it's true, it's still a lack in my understanding of how people are and a lack of realization of how different, unusual my own thoughts about things can be. It’s made me feel despondent and set apart from people. That especially holds true for Brexit. With the US, my mind can basically set everything apart as “Oh, it’s just like the Wild West. It’s just like a cowboy film.” I’m far enough away to be able to do that.

But the situation with Brexit is so similar to what's happened with Trump. Our town, Tyne and Wear, became the poster town for Brexit, because we always count our votes first. We were the first town to declare we wanted to leave the EU. It certainly made me feel “Maybe I don’t like my town anymore. Maybe I don’t like the people who I have to talk to every day.” That’s a childish way to think about it, but those are the sorts of emotions I’ve experienced at times.

At the moment, I can't see how we move on from that. Even the difference for global politics that remains if Trump gets voted out this year is huge. He didn’t create the partisan divide, but he exacerbated it and it’s not going to go away. The same holds true for the media divides. Things might even get worse. It feels like a very difficult and awful time in Western culture.

Prior to Field Music, you and Peter were involved in two groups called New Tellers and Electronic Eye Machine. Tell me about them and how they led to Field Music.

When I started playing in bands, we played covers in pubs. We lived out our dreams of playing Led Zeppelin and Doors songs—whatever we could play with a Hammond organ, which is what Andy Moore played at the time. There came a point where we realized that we played a lot of music, but we didn't really listen to music. From when I was about 17, the exploration of listening to music really began in earnest. I had to throw away so many of the ideas we had before about what music we wanted to make.

In the process of doing that, I think me and Peter decided that we would have to do it separately in order to really follow these ideas we had. We each had to be individually in charge. That era lasted quite a long time, but what we were both doing with New Tellers and Electronic Eye Machine was just trying to rid ourselves of rock and guitar band clichés. We made things very difficult for ourselves because we refused to just have a band with two guitars, bass and drums. We never did more than four gigs with one particular lineup of a band, but there were enough people on the periphery of the music business who thought we were interesting enough to see where we might go with this.

We had a manager at the time who had so much faith in us—really unjustified faith in us. He managed to get us a publishing deal in a time when the music industry still had money to splash about, and find someone who was willing to put out an EP of these not quite fully-formed ideas we had.

Me and Peter were involved in every New Tellers and Electronic Eye Machine gig. We were really making things awkward for ourselves. Initially, it made sense because the New Tellers, which was my band, was going to be something where the music was almost unplayable and there were going to be lots of electronic, minimal elements. Electronic Eye Machine, which was Peter’s group, was going to be like a jamboree and there were going to be loads of people on stage playing loads of different things. Everyone was going to have these intricate parts and it was all going to slot together. The truth is, I wasn’t ready to have a band with loads of people in it I had to marshal around, because I just socially couldn't have dealt with it then.

When it got to the point where we're just in the same four-piece band with two different names, it was like let's find a way in between these two things and actually make a record. We wanted to see if we could find a way to compromise a bit with each other so we could make a real album. That’s really what we wanted to do. We wanted to make a real record, not an EP that ends up on the shelves of some of the shops, but which no-one ever hears, which is how those early records felt.

That's when we realized this very simple thing. It's like well, whoever comes up with the initial idea for the song is in charge. We'll have a little revolving dictatorship. [laughs] We don't have to decide everything together, but the lineup of the two bands were almost to the point where they were the same anyway. We thought we really should just do one thing. There were years of flailing around trying to do something interesting and beyond what we had the technical capabilities to do.

We were quite inspired by seeing The Flaming Lips around the time of The Soft Bulletin album where they went on stage and didn't have a drummer. Sometimes the drums were on a projection behind the screen and the music sounded really strange. We thought, "Okay, well you don't have to do a normal band. You can do anything." We just didn't realize that was much harder to do.

Photo: Andy Martin

Photo: Andy Martin

Discuss the art of survival for Field Music as it relates to this brutal era for musician compensation.

I think we have very fortunately chanced upon a way of making things work for us. We were very fortunate to get started before the economics of the music industry had really changed to a kind of lull before the real download revolution hit. But even then, what we realized artistically early on was that we just wanted to be in charge of things. It was less painful and took less time for us to learn how to do something technically than it would be for us to explain what we want to someone else. I’m talking about having to depend on a recording engineer, a mastering engineer or a mix engineer. We learned how to do things ourselves.

So, we've become recording engineers by accident. We realized we could have our own studio space. We live in a very cheap town to exist in. Space is cheap because it's a struggling post-industrial town. With just a little bit of money, we can find enough equipment to make something, as long as we're prepared to do everything ourselves.

We're fairly sober people I guess. We did some gigs with bands like Deerhoof and Menomena way back when. We saw how they just sorted everything out for themselves. They didn't have to have an entourage. Whereas the first thing the bands in the UK do when they've got a record out is like, "Oh right, well let's have a guitar tech. Let's have a driver. Let's have all the extra luxuries so we can have a few drinks and a good time after the show." We've managed to tone down our indulgences just to look after ourselves and make touring work in a similar way to how we've made the recording work, by just doing everything ourselves. We don’t have a driver, for instance.

There might come a point for us where the revenues from making a record drop so much that we start to really struggle again, but I'm hoping we'll find other ways to make it work.

Both you and Peter have described the early days of Field Music as a particularly difficult financial undertaking. Reflect on that period.

Up to 2010, things were really, really tight all the time, but that was really just the delay it took in order for people to find the records. By the time we did Measure in 2010, people had time to find the first two records. Suddenly we were playing to audiences of more than 20.

We figured out how to tour when we didn't have any money to do it. We would pile into my dad's car. It was like, "Dad, can we borrow your car, because we've got a festival?” [laughs] Because we learned how to do it then, when we actually started getting proper fees for gigs and people were coming to the shows, we were kind of able to capitalize on that in our very modest way.

We can't indulge ourselves. We can't afford to spend money if we don't really think it's justified. I’m always surprised on my Facebook feed to always be getting adverts for musical equipment. I just think, "Who can afford to buy these things? Not actual people that work in bands. These are things you can buy if music is your hobby and you have a real wage with disposable income you can spend on gadgets.” We just can’t do it.

Field Music has vast critical acclaim. Yet, there’s a huge gulf between that acclaim and the economic traction you’ve experienced. What’s your perspective on this?

Yeah. I think there are different things going on. I think part of the critical acclaim comes from the fact that we approach music in quite a similar way to how a lot of critics approach it. We take the music seriously. We try not to take ourselves too seriously. We want to make music you can really dive into and keep finding new things in it. I think there are still a lot of music critics who approach music in that way. I'm also really aware that we make music which is quite niche, and I think it's because me and Peter are kind of unusual people.

For a while, a lot of people said, "Are you going to have a moment like Elbow?" Elbow won the Mercury prize here and went from being a respected, but not huge band, to suddenly having a connection with a lot of people. I think what they always had as a band was that they made music which invited people in, and they were reaching out to people with the lyrics and the feel of their songs. I think me and Peter are much more difficult people. In trying to do something which is really honest and really true to who we are, I think we've made music which puts a barrier up to that happening. We aren’t inviting people in. I’m not that kind of person. In doing something genuinely authentic, we've set ourselves apart from the kind of listener who wants to engage in those emotionally-satisfying moments. We don't make them—or not often enough or not in the songs where it would make it count. We have the emotionally-satisfying moments in things like big, epic, unusual orchestral blowouts, which aren’t the kinds of record which are going to get played on radio. It's barely even the kind of song we can play live, and even then, the emotionally-satisfying bit is just a tiny kernel. We didn't take that emotionally-satisfying bit and make that the chorus of the big tune which is going to get on the radio, and we'll never do that because it's just not what we're like.

There are amoral commentators and industry people who openly and brazenly question musicians’ entitlement to a living wage. What’s your reaction to them?

On one hand, I think if someone is creating something great and people are listening to it, then they should absolutely get paid properly for having made it. You're making something of real value. On the other hand, there are a lot of musicians who want the indulgences of being in a band. They want the indulgences of making a record and aren't being realistic about the range of value that might have. I find the crowd-funding approach to getting a record made difficult, because I think a lot of that is people wanting to make a record in the old way in which lots of people do things for them.

My favorite thing about albums is that they’re pieces of art everybody can own. A great album is relatively inexpensive for a person to buy. Even in the CD era it was 10-15 pounds an album—something you can get years and years of listening from. Now, the idea is, if you’ve got the money, you can have the album, and some better things as well. The band will come and play in your kitchen. That’s not something available to people who just love the album. I have mixed feelings about that. Although once people stop buying our records, maybe we'll have to do that as well.

How are things going for Field Music in terms of physical media sales?

We’re still doing okay in terms of selling records. We've started putting more and more effort into making sure that the package for the vinyl is nice. It’s a small, but appreciative audience for the physical version of an album. Maybe that’s clinging on in the UK more than it is in the US.

I don't think Spotify or the Apple Music subscription type things are as prevalent here, although certainly becoming more so. Maybe it's just something which really overlaps with our audience. The audience for our kind of music is very much one that wants to have a physical version of the record in their record collection, which they look after.

I was looking at a piece on School of Language’s 45 album on a magazine’s website before speaking to you. On one side of the page is a review and interview with you. On the other side is the Spotify embedded link to listen to the album in its entirety. So, the reader reads the interview and plays the album, and then they’re done and you’ve literally earned three cents. The entire interaction with your piece of art may begin and end there.

Yeah. It's indicative of a really strange time in the economics of the music industry. That side of things is probably not going to be great for us, because we don’t make music that’s very immediate. We still make albums that are structured as albums. We don’t do the kind of records where there are two standout tracks which you know will make it on some playlist and the rest is filler. We refuse to do things that way because our love of music comes from a love of albums.

We’re conscious of the situation you’re describing and we’re trying to sustain things the way we have. We’re probably in as good a position as anybody—certainly for anybody who sells our level of records with our level of fame. We’ve committed ourselves to being wholeheartedly self-sufficient and we hope that keeps working.

“We Are Making a New World” oil-on-canvas painting by Paul Nash, 1918 | Photo: Imperial War Museum

“We Are Making a New World” oil-on-canvas painting by Paul Nash, 1918 | Photo: Imperial War Museum

Peter Brewis

Tell me your view on the beginnings of Making a New World.

Field Music and the Imperial War Museum have a mutual friend, Andy Martin. He's made videos for us before. He's involved with quite a few of the visual aspects of Field Music. He said that somebody from the Imperial War Museum was interested in having Field Music do something, and would it be okay for them to get in touch? That was our first point of contact.

The Imperial War Museum was doing this exhibition called Making a New World, which is based on the painting “We Are Making a New World” by Paul Nash. He was one of the official painters for the British in the First World War. So, the museum wanted to include some music. Now, I think they had lined up The Fall to come and play, but they couldn’t. I think this was before Mark E. Smith had died. So, they approached us and we said “We'll do something, but can we do something new? Can we make up some new music that we think could be linked to and inspired by aspects of the First World War?" The exhibition was really about the aftermath of the First World War, not the actual war itself. The more we looked at it, the more we found many interesting stories.

My initial idea was to do something which wasn't song-based. I thought it was an opportunity for us to do something slightly improvised. I was kind of thinking about jazz at the end of the First World War and what the ensembles and sounds might have been. I was also thinking about early 20th century composition. Prior to the First World War, during the Belle Époque, there were these big, bombastic orchestral works for massive orchestras, such as Stravinsky’s “The Rite of Spring.” During and after the First World War, resources were diminished in terms of people and money, and this constrained things. I thought we could do something instrumental that reflected and drew upon the music of the period. But the more we looked at it, the more we realized we could write some songs about these stories which grew out of the First World War. These stories had quite long narratives stretching up to 100 years.

What do you believe society can still learn from the First World War?

That’s a big question, but I do believe people can still learn from it. I suppose what I learned was that this terrible, cataclysmic event, which only lasted four years, had a huge impact on technology, society and the arts. The war also had an influence far beyond what we even imagine. We only scratched the surface with our research on its massive repercussions.

With tiny events, once something happens, it's done and you can forget about it. But the shock waves of a big, big event like a world war last forever. However, our memories of them, our interpretation of the actual event and our feelings surrounding that, perhaps die with the people who actually experienced it.

Given the complexities of these challenging times and what you explore on the new album, what’s your view on the positive value music can have today?

Sometimes I wonder whether it has any value other than just being entertainment. That is at my least confident. But sometimes I think “I'm in a very privileged position in a nice band with my brother, and we do whatever we want.” The only thing we really need to worry about is paying the bills so we can survive and make the music we want. And if we're in this privileged position, then maybe it's our responsibility to, as Todd Rundgren once said, "Try and do something nobody else can do."

I'm not saying that our music's particularly original or anything. But I think that the way we approach things and hopefully the way they come across have a certain individuality. I think it's our responsibility to make sure it's individual and maybe talk about things that concern us.

I don’t know if we’re actually giving voices to anybody else. Maybe we are. It's something I wonder about all the time. Is there a political role for what we do? If so, what are our responsibilities as musicians who have been given such a nice life? As I said, we're in a very privileged position. We don't live in Syria. We don't have any forest fires here like California. We have to deal with some things, but it's nothing that's really threatening our lives. So, maybe that puts us in a position of having some responsibility to do something of worth.

Photo: Andy Martin

Photo: Andy Martin

How do you feel the creative process for the new album diverged from earlier Field Music work?

Initially, it was a commission. We were allowed to do what we wanted to do, but it had to fit the brief. And it was basically a concept from the very beginning, which isn’t really the way that we've done anything else before, other than the soundtrack Music for Drifters. It’s also different because this was going to be a bunch of songs that we were going to have to rehearse with the band first. In terms of lyrics, we weren’t talking about how we felt about things, though maybe we did so in a covert way. But the songs are really about very tangible, historical subjects, which is something I haven’t done before.

Learning to play the songs through live performance is something we've never done before in Field Music. We've always made a record first and then thought, "We don't know how to play any of this." This is the first time we've played songs live with the band, and then recorded them with the band. We recorded the bulk of the songs after we played the second gig. We ran through all the songs twice, and we picked the best takes. And then me, Dave and Liz Cornish did a couple of overdubs. It was very freeing to do it like that. It was very different and felt like a good thing to do.

What were some of the biggest challenges you faced in translating these ideas into songs?

The first challenge was finding the stories and picking the ones that we liked. There was very little vetoing going on. I picked the ones I wanted to tackle, Dave picked the subjects he wanted to tackle. We wrote the songs and we just slotted them in. There's very rarely a time when I say, "You know what, Dave? I'm not really keen on that song. I don't trust you on this song." We just trust each other and that our intentions are acceptable. I think we also trust each other not to be shit. Well, I trust Dave, anyway. [laughs] I don't want to know what he thinks of me.

After we found the right stories, I really didn’t want to make things trite. I didn't want to write songs that said, "War is bad. Peace is good.” I think we tried to find the stories that said something about the war, the end of the war and its aftermath that resonated and still maybe had some relevance today. I think we always try not to make the music or words too dramatic or prescriptive. I would like the music and words to make people wonder about the stories and then make up their own mind about how they felt about them. I didn't want it to come across with any bits being sad or happy. I think that's a challenge when you're writing stories from the point of view of somebody else. These stories are quite precious, in a way. And I felt a responsibility of handling them correctly. I didn't want to make them into a bad musical.

Let’s explore some songs from the album, starting with “A Change of Heir.”

The song is from the point of view of one of Harold Gillies' patients, Michael Dillon, who experienced one of the first sex reassignment surgeries back in 1946. He was originally named Laura Dillon and when he had that name, he wasn’t entitled to the Dillon family fortune. But when he became Michael, he was male, and was able to become the heir. His dad was a baron. After he’d had this pioneering gender reassignment surgery, there was a massive fuss made. He decided to escape to India and wrote a book on transsexualism.

In the song, Michael’s saying “ I wrote my book. I changed my name. I was told I was next in line. A change of air, a change of air. A change of heir, a change of heir.” So, the pun is “a change of heir.” He was an heir and went somewhere else for a change of air.

Gillies, who performed this gender reassignment, is considered the godfather of plastic surgery. The skills he used on Michael were learned performing operations on soldiers coming back from the First World War who had been mutilated by shells, gunfire and gas.

It was one of the stories where there’s a definite beginning in the First World War and an aftermath which goes much further, continuing to this day. I thought it was a decent, interesting story to write about. I wanted to handle it in a way which doesn't tell you the full story, but hints at it, making the listener maybe want to try and find out a little bit more about it themselves.

“Coffee or Wine.”

David wrote that one. My view is it's talking about the signing of the Armistice. The generals get together after all of the carnage and all the destruction and as they’re getting ready to sign it, say “Right, who wants coffee? And who wants wine?" And I think it's Dave's way of saying that these guys have been in part responsible for life and death, and maybe they’re slightly removed from the real, human devastation that's gone on. And while signing this Armistice, one of their decisions now is to decide on what sort of refreshments they want.

“A Shot to the Arm.”

It’s about an artist called Chris Burden and his famous piece “Shoot.” I suppose what I'm doing on the song is I'm linking the birth of the Dada movement and the First World War. I’ve hidden some lyrics from a Hugo Ball poem in there. I hope I've hidden them well. The Dada movement was born in Zürich, Switzerland as an anti-war, anti-First World War art form, which included poetry. It was also the birth of surreal performance art.

So, I’m also linking Hugo Ball to Chris Burden. Burden asked his friend to shoot him in the arm and it went kind of wrong. His friend was meant to graze his arm, but actually shot him in the arm. It was a reaction against the media’s portrayal of the Vietnam War. He was trying to say that we never really saw enough about what actually happened. News reports came in, but you never saw what it was really like for someone to get shot and have a burning hole in their flesh.

There’s a lineage between the Dada movement and what Burden did. Burden was also interested in the idea of children’s toys training you for war—like guns, lightsabers, and bows and arrows. The song also deals with the idea of the playground being a performance space for kids to test their soldierly attributes on one another.

“Beyond That of Courtesy.”

There was a conference at the Paris Peace Conference in 1919, where the League of Nations was drawn up. And the French Union for Women's Suffrage had a parallel Paris Peace Conference. I think it was called the Inter-Allied Women's Conference. And they tried their damnedest to be involved in the drawing up of the League of Nations rather than it just being a bunch of white, male Europeans telling the world, "This is the new world order. This is going to be peaceful and we're going to decide how to make it happen."

The French Union for Women's Suffrage said "We should decide what the world's going to be like as well. We're the ones who've been oppressed. We're the ones who know about all the inequalities that are happening. How many women are still in servitude? We need to be involved in this. And we don't want to be invited just out of courtesy." That was it, really. It was about them saying "We want to have a say."

Photo: Beth Maples

Photo: Beth Maples

Reflect on the band’s self-titled album from 2005 and its follow-up, 2006’s Tones of Town.

The first album was, in a way, a mistake. It was an accidental album that created an accidental band. Me and Dave had been doing our own thing, previously. We worked together on an album and intended for it to be called Field Music. It was the name of the album, not a new band. But we realized that didn’t help with marketing. We needed a name. So, rather than naming the album after the band, which happens a lot, we named the band after the album.

Then we thought, "This is a good band name, because it doesn't sound like a band." It has different connotations. It could be construed as computer game music, military music, field recordings, and other things like that.

Those first two albums were where me, Dave and Andy Moore, the original keyboard player, figured out how to be a band, again. We've been in bands before—blues and rock groups. With Field Music, it was about determining how to integrate the new things that we learned about music along the way into the band.

I suppose the model for the band was The Beatles, in a strange way. I don’t mean it in a "Let’s take over the world, be famous and get on The Ed Sullivan Show" way. Rather, I mean in a "Right, how do we convert the things we all like in music, including the disparate elements, into songs can listen to with structure and hooks?” That was the beginning of the continuum. And I think we've been doing that to a greater or lesser extent ever since, really.

There was a four-year hiatus between Tones of Town and 2010’s Measure. Tell me your side of the reason for the group pausing between those recordings.

I think we realized that after Tones of Town, we couldn't afford to do the band in a normal way. We couldn't have the three of us touring all the time. We just weren't successful enough. We didn't earn enough money. And I think we were all a bit upset about the whole thing in that it hadn't worked and that we hadn't found an audience.

We also realized our competition were other guitar-based indie bands. And there were a few moments where I just thought, "Do you know what? I don't want to be in this game. I don't want to be in this competition. I'm not interested in that. So, let's just stop the band." I went back to university. Dave did the first School of Language album, and I did a project called The Week That Was. Andy went back to the world of food science and has been there ever since. We miss him being in the band dearly. I still speak to Andy every couple of weeks and see a lot of him.

Eventually, we decided "Let's do Field Music again, but let's play the game. Let's admit that we're in the indie, guitar game. But if we're going to use guitars as the main thrust, let’s make an album that’s the sort of rock album we would like to make." We really drew upon music like Led Zeppelin, Roxy Music and 10cc. We used those models as frameworks for our own musical and lyrical language.

We had a lot of fun making Measure and playing together. We imagined we were different people. And it kind of worked, because it meant we could go out and tour it and we could play live fairly easily. We ended up finding an audience for what we do.

Tell me about the advantages and drawbacks of collaborating with David for so long.

The benefit is that we both have the common history and language, and we're extremely tolerant of each other. I think we know what each other’s skills are. I know when Dave can do something better than I can do it. It’s good to know “I need Dave to do this bit. I need Dave to play the drums on this, or to play a guitar on this, or to play the bass on this or to sing this part.” It’s also about trust as well. I trust him to say what he thinks. It's not like we can split up. I think we're probably beyond that now. I think we always know that we can go and do other things, so there's no panic.

I think the difficulty is that maybe sometimes we get complacent with each other. And because we both understand what we're getting at, maybe sometimes we're not able to communicate that all the time with other people. I think that's one of the challenges.

Another thing is that we need to make sure we don't get bored of each other doing the same old things. We're aware of this and I think that's something we're able to nip in the bud if we feel it coming.

Both Dave and I have had difficult personal times as of late. I'm the sort of person who, when things get difficult, gets paralyzed by it and turns very nervous. I deal with it by hiding away. Whereas Dave seems to deal with it by working even harder. I think during the past couple of years, especially with this record, Dave's taken on the bulk of the legwork. He was setting up the studio as well. That’s something I think we're both very aware of. And hopefully I'll make it up.

You Tell Me: Sarah Hayes and Peter Brewis | Photo: Andy Martin

You Tell Me: Sarah Hayes and Peter Brewis | Photo: Andy Martin

Let's talk about the beginnings of You Tell Me and the pursuit of its 2019 self-titled album about conversation and communication.

Emma Pollock from The Delgados was putting on a celebration of the music of Kate Bush called Running Up That Hill in 2016. She got my number and said "Would you like to come and sing some Kate Bush songs?" I was very apprehensive about that because Kate Bush is one of my favorite singers, songwriters, musicians, record makers, and producers. I definitely didn't want to make a real hash out of the songs which I really loved. But the thought of going up to Aberdeen for a couple of days and doing this really appealed to me. So, I decided "Oh, go on. Let's do it." I was very nervous about it. I did “Mother Stands for Comfort,” “All We Ever Look For” and “Sat in Your Lap.” Quite difficult ones to do, really. But the band was amazing.

Sarah Hayes was in the band, playing keyboards and doing all the weird Fairlight keyboard sounds. Then she sung “This Woman's Work,” and I thought “Wow, that’s just phenomenal.” There were loads of good singers there, but Sarah was really something else.

Sarah and I got chatting afterwards and I realized she was from not very far away from where I was from. She was from Northumberland. And she was a folk flautist, singer and composer, and was in a band called Admiral Fallow. She said she'd been trying to write some songs—the first ones she’d ever written. She showed me them and they were, again, just great. Really brilliant. The work reminded me of lots of different things. There were bits of Rufus Wainwright, Christine McVie, Fleetwood Mac, and The Blue Nile in there. And obviously Kate Bush and John Grant. I was just astounded, really.

She asked "Would you be up for producing my record?" I said "Yeah, I'd love to if you think I could do anything with it." Within two hours, she said "Well, why don't we just do a band—just me and you?" And I thought "Well, I don't really want to have to write songs that measure up to your songs. And I don't really want to have to sing and be the worst singer in another band." I was very nervous about writing songs that were as good as Sarah's and singing with her as well. I had to really up my game. And it really was a very nerve-wracking, quite difficult experience in some ways. But I'm very glad that I did it because I learned a lot from Sarah.

Sometimes me and Dave need outside experiences to bring back to the Field Music table and say "Oh yeah, we've learned these things. We've tried out these things. And let's come back together and share what we have and what we've learned."

You’ve said the album took you out of your comfort zone. How did it do that?

I had to handle Sarah's material and I didn't want to fuck it up. I just thought Sarah's voice and songs had so much potential. I didn't want to be the one to make a mess out of it. I don't mind making a mess out of my own songs or even Dave's songs, really. If Dave insists on letting me mess up his songs, then that's fine. [laughs] But I thought Sarah has so much potential. It was a lot of responsibility to try and make sure I did her and the material justice.

The other thing was, she could get a producer who had a bit more of a profile and maybe could actually set the world alight with these things. And I didn't want to be the one to hold her back. And then the idea of actually being a band where I contributed songs as well made me nervous. But she was nervous too. She'd never written songs before, so I think it was quite nervy for both of us, really.

Explore the theme of the album and why it’s important to you.

Well, I think the theme was accidental, really. Because I think we just basically both wrote songs about talking to people, not being able to talk to people, letters and conversations, and being alone, and being with people. I think it was only when we came to write the press release we thought, "Oh yeah, these songs are all about figuring out ways to communicate things to people and failing, and succeeding sometimes—and all the positive and negatives that go with that.”

One of the things was just me and Sarah being able to communicate. It's easy for me and Dave to communicate. Sometimes a raised eyebrow from him can say a lot that I immediately understand. That’s something that happens a lot between brothers. But with a new friend, it's like, "How do we find a common language here? How do we find a way of working together and creating a vocabulary?" I actually think a lot of the songs are about, in part, making the album itself and the intensity of communicating with somebody new.

Reflect on your other solo project, The Week That Was, and its 2008 self-titled album, recorded during the late-2000s Field Music hiatus.

That's the hardest I've ever worked on anything in my life. I think I had to prove that I could do something on my own outside of Field Music, and me and Dave. Once I did it, I never felt trapped again, doing anything.

I knew what I wanted it to sound like. I think the idea was of a lost future. I wanted to make the album emotional, without being particularly performance-based. It was a nostalgic record as well, in that I'd rediscovered Peter Gabriel—his Melt album, in particular, Kate Bush’s The Dreaming and Japan’s Tin Drum. These were albums made with Fairlights. I basically converted my MacBook into a surrogate Fairlight. I also learned how to play the piano again. I drafted Andy Moore to play piano on a few songs, as well.