Donate to Innerviews

Since 1994, Innerviews has provided uncompromising, in-depth interviews with musicians across every genre imaginable. And it does that with no trackers, cookies, clickbait, or advertising.

Your donations are welcome to help continue its mission of highlighting incredible music and artists, without any commercial considerations.

Your contributions will be instantly transformed into stories and videos, and cover hosting and web management costs. Importantly, your dollars will help ensure Innerviews remains absolutely free to all visitors, independent of their ability to financially support it.

Please consider making a donation today by using the PayPal QR code below.

Gang of Four

Outsider Culture

by Anil Prasad

Copyright © 2025 Anil Prasad.

Gang of Four, 2025: Hugo Burnham, Jon King, Gail Greenwood, and Ted Leo | Photo: Jason Grow Photography

Gang of Four, 2025: Hugo Burnham, Jon King, Gail Greenwood, and Ted Leo | Photo: Jason Grow Photography

Gang of Four ripped open and rewired punk rock with jagged guitar, danceable rhythms, and a Molotov cocktail of intellectual political critique. Formed in 1976 in Leeds, the group remains one of the most incendiary and innovative bands to emerge on the post-punk scene.

Its original lineup featuring vocalist and lyricist Jon King, guitarist Andy Gill, bassist Dave Allen, and drummer Hugo Burnham scaled tremendous heights on the group’s first two albums, 1979’s Entertainment! and 1981’s Solid Gold. Both fused angular riffs, a funk-infused pulse, and provocative language that challenged capitalism, consumer culture, and political apathy. The band’s name was taken from a Maoist group of Chinese Communist Party officials, signaling their commitment to a critique of systems of power.

King served as the intellectual and ideological heart of Gang of Four. His urgent, impassioned vocal delivery underlined its songs’ themes of alienation, commodification, and the manipulation of desire. Together with Gill’s creative avant-guitar lines and the explosive rhythmic approach of Allen and Burnham, the band’s sound remains hugely influential across punk, indie, and even hip-hop realms to this day.

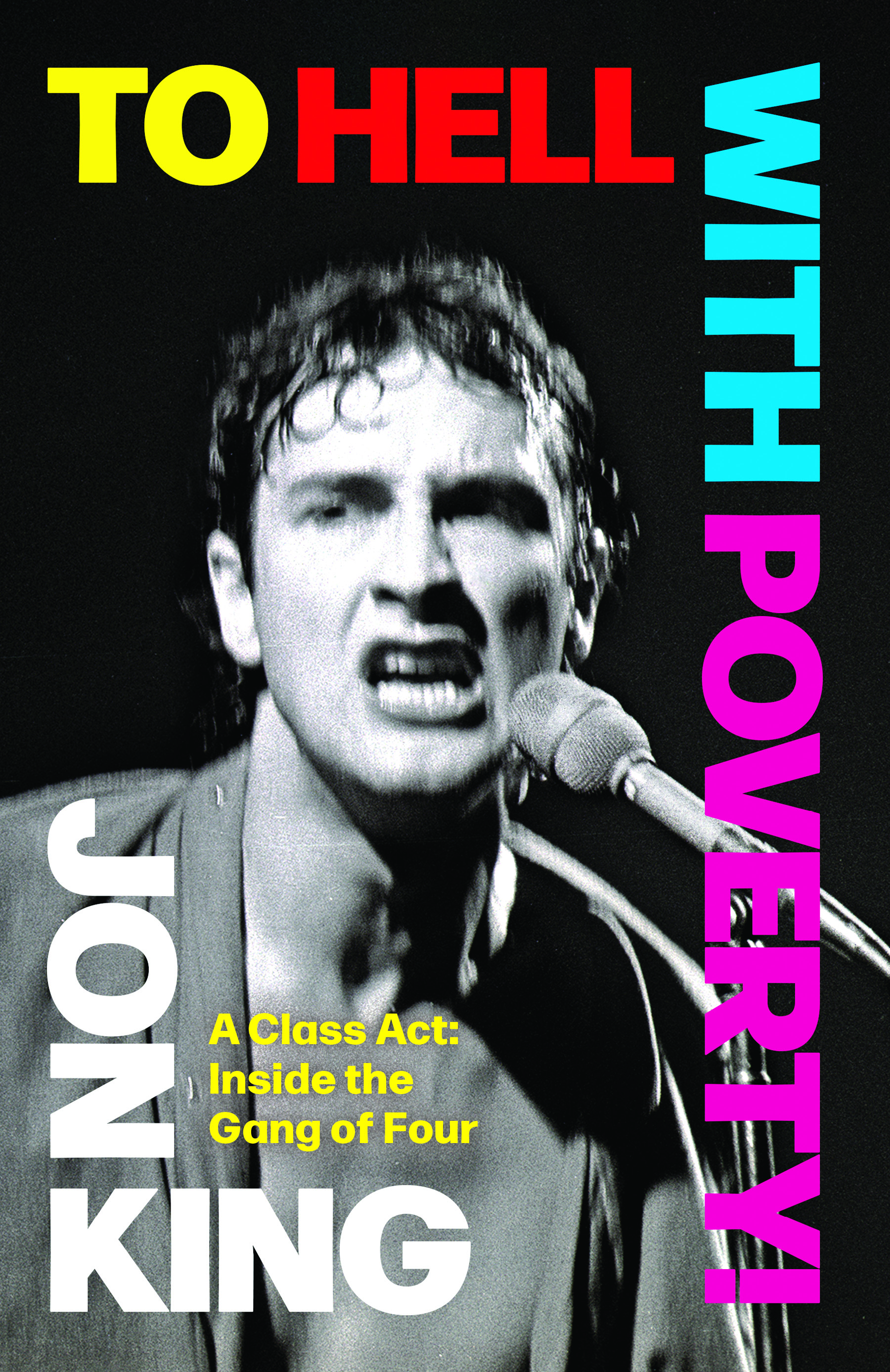

This year, King released To Hell With Poverty! A Class Act: Inside the Gang of Four, a hybrid memoir and group history that explores its origins, context, and lasting impact. It also offers a deep dive into the political and cultural landscape of late-1970s Britain, the making of its first four albums, and King’s reflections on the turbulent interpersonal dynamics within and beyond the quartet. In addition, it documents the philosophical underpinnings of Gang of Four, connecting its lyrical concerns to a broader framework of dissent and resistance in music.

In July 2025, Gang of Four concluded its farewell tour. It brought a powerful sense of closure to the band's long journey. Featuring a lineup that included King, Burnham, bassist Gail Greenwood, and guitarist Ted Leo, the shows centered around live performances of Entertainment! in its entirety, as a tribute to the album’s enduring legacy. The gigs were raw and provocative, capturing the rage and energy that originally defined the band. King has not ruled out occasional future one-off performances.

Gang of Four’s recent years have been marked by loss, in addition to celebration. Gill passed away in 2020, and Allen died in 2025. Their deaths added a layer of poignancy to the band’s final concerts, not only musically, but through projected visuals showcasing their highlights with the group across the last 49 years.

King spoke to Innerviews about his book and the group’s farewell tour, in addition to exploring rarely-discussed Gang of Four albums and history.

Jon King Collection

Jon King Collection

What are your thoughts about the value of music during this period of socio-political strife?

I think if we people who have progressive politics and that mindset fight battles using the language of our opponents, we’re almost doomed to fail. In Britain, there’s a conversation happening that there are too many people coming in on boats. It’s probably true, but it’s irrelevant in the big picture. The big picture is that the population is declining and actually, we need immigrants. But if you don’t change the territory of the conversation, you’re going to lose the argument.

I think we’ll be saved by culture. Very recently, South Park, which is on Paramount, did a segment in which they have Trump having a conversation with Satan every day. It’s brilliant and funny but also has a serious point to it.

In the 1970s and 1980s, I was very much involved with Rock Against Racism, which was a response to Eric Clapton who had very vocally shouted out support for a hard right racist politician. The majority of British musicians got together and said, “We’re not going to allow this to stand. What we’re going to do is show that we love each other from whatever our origins and heritage. The world’s a better place with that.”

The result of that was the hard right parties, who were then on a roll, weren’t re-elected. And there has never been a single hard right politician in this country since, in the way that has happened very sadly in the United States. So, I think that was something that was really important.

I’m shocked at how little music there is that says anything about the world right now. Were I writing now, I don’t know how I could avoid writing about what’s going on. I’m a musician, not a journalist or a politician, but you write about the things that matter to you.

When you performed during recent Gang of Four tours, you had Black Lives Matter, LGBTQ, and anti-fascist action flags draped behind you. Did you feel a sense of renewed relevance for the music given the times we live in?

I very strongly did on this last tour. I’m not a hugely sociable person. I was never in the habit of going out front to meet the audience in the past after shows. I’m quite exhausted after shows and like to sit on my own. But during this last tour, I did. I went out every night for about an hour to talk to people at the merch stand.

Obviously, there was some self-interest in there, but it was also very moving for me. I was taken aback by all the people who told me about their personal stories. Many of them said, “Thank you for doing this.” I was quite overwhelmed by it, because I hadn’t really thought about the music as some kind of public service. But I was actually in tears a couple of times after meeting people.

I was also struck by how many young people were there. I’m officially an old person. But generally, the estimate was about a third of the audience were Gen Zers under 25. And many of them would say, “Why isn’t anyone else doing this?” Some of them had just discovered the band, possibly through streaming and YouTube. But it seems to have resonated with that generation.

The Gen Z people noticed the flags. Sometimes, halfway through a song, the audience would cheer and break out into applause. And I was thinking, “Hang on, I’m in the middle of a verse.” Then I’d turn around and see that on the screen behind me, it would say “Stop bombing Gaza” or “Fight fascism.” It was really interesting to experience. I was struck by that. And it wasn’t just in America. It happened during our European dates, including Paris, which is quite often thought of as a very restrained place. But the crowd was going nuts, responding to the messaging.

The same thing happened when we did a couple of nights in Dublin. Paul McLoone, the lead singer of The Undertones, came along and said, “I want to say thanks because Gang of Four was the only mainland band that was writing about what was going on in Northern Ireland.”

I don’t know whether that’s true or not, but I hadn’t really thought about how much I had written about Northern Ireland until recently, when we played Entertainment! track by track on the last tour. The opening song “Ether” offers a classic, oppositional way of writing with the lyrics “Trapped in heaven lifestyle (locked in Long Kesh).” The record company didn’t like us starting the album with that.

The context of this false consciousness we have—you know, these wonderful times we live in—comes at the expense of misery somewhere else. We’re happy to have cheap T-shirts. But people are being paid five bucks a day to make these t-shirts. So, you have to decide if it’s possible to buy a t-shirt for five bucks without someone being put in misery.

Gang of Four, 2022: Jon King, Sara Lee, Hugo Burnham, and David Pajo | Jason Grow Photography

Gang of Four, 2022: Jon King, Sara Lee, Hugo Burnham, and David Pajo | Jason Grow Photography

In 2024, David Pajo, who joined Gang of Four in 2021, said he was preparing to tour with the group again in 2025, and intimated that he was working on new music with you. How did that shift into a farewell tour with Ted Leo replacing him?

It was David’s decision to leave. He wasn’t feeling very well. We’re great friends. David and I have great love for each other. He’s doing amazing things with guitar now, which is what he’s really concentrating on. We’ve spent time together writing new material. What I didn’t want to do though is write a Gang of Four record.

I was really pissed off when Andy Gill made, effectively, three solo albums, which were called Gang of Four. I don’t think unless you’ve got at least two of the three original founding members that it’s a possible thing to do. I think the music we’ve written will not be a Gang of Four record. And were I to write, hypothetically, with Ted Leo. It would be something else. So, that’s really it.

These shows are the end of touring. I don’t want to tour anymore. And I wanted to give Entertainment! a proper send off. Originally, we talked about doing something to mark the 45th anniversary of the album coming out.

You always wonder as a musician whether what you did was worthwhile or not, and whether it’s worth doing again. But I’ve always been a great lover of blues music. I remember going to see Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee when they were likely in their eighties. So, you can play for as long as you like, really.

Touring is the way Gang of Four shows what it can do. And I really didn’t want to do a half-assed thing. I was really pleased at the way we could still do an incredibly intense show night after night after night. Every night, I thought, “Wow, that was just incredible.” I’d be exhausted and think, “We can’t do that again.” I was waiting for there to be an average show and there never was.

So, I don’t want to do this anymore, but I won’t rule out performing in the future in some other format. There might be a festival we choose to do. But I don’t want to tour any longer. I think I’m done with that.

What went through your mind after the final encore of the final show on July 5th at the Paradiso in Amsterdam?

It was funny in the sense that I didn’t really feel anything transcendent. The Paradiso was where I think we played our first ever show in Europe, and now it’s where we played our last show ever in Europe. It’s a wonderful place. I love it there.

The show was really amazing. But I remain in that quite familiar school of gloomy musicians who always wonders if anyone will turn up. I once saw an interview with Ozzy Osbourne, just a day or so after his death, during which he said, “Will anyone be there?” And that’s when he was playing 20,000-seat stadiums. So, I felt that too about The Paradiso, but of course, it was sold out.

It was such a fabulous show. I thought, “This is such a great band. Having Ted Leo, Gail Greenwood, and Hugo Burnham as the group was just a tremendous thing. But I also felt, “We’ve done it.”

To use an art analogy, there was a famous painting by J. M. W. Turner, a great British artist, that he exhibited at the National Galleries or Royal Academy. He hung this great big painting up. He was very competitive. John Constable also had a painting in the same gallery—one of his great works. Turner turned up and saw that his painting was maybe not going to get the attention it deserved. He felt it deserved the private viewing arrangement that Constable’s painting had. So, he went home, came back with a little pot of red paint, and painted a bobbing barrel in the middle of the sea. It was this tiny little blob of red. And it was like a magic trick. And I felt, “Yeah, that’s it.”

One of my favorite pieces of music is “Cantata BWV 82” by Bach. During this piece, there’s an aria called "Ich habe genung," which translates into “I have enough” or “I am content.” And I think yeah, it is enough.

Your book To Hell With Poverty! covers the beginning of the band through to the end of the Hard period in 1984. What made you want to focus on that timeline, instead of continuing the Gang of Four story to its conclusion?

It was a natural break. I think had I carried on beyond 1984, the book would have been a massive door stopper. When I got the assignment, the target was to write 80,000 words, which seemed an unfeasibly large amount initially, until I worked out what I was doing.

There were definitely two halves to the band. There was the period up until 1984, which ended with a catastrophic meltdown. We were robbed of everything we had. It was stolen from me and Andy Gill by our manager. Every penny. So, I had nothing. There was a dramatic arc to it, and it was sort of blackly funny.

We’d gone on tour to pay our debts and put some money in our pockets. But Andy had testicular cancer, which is mentioned in the book. He was really ill during those last months in 1984. So, I said, let’s just pack it in and go bust. But Andy said, “No, I want to carry on.” However, I didn’t want my friend to die for the band.

So, the moment that tour finished, Andy went straight into Mount Sinai hospital to have this very major surgery. And it was just a point when everything was sort of collapsing. Of course, while he was in hospital, I got the job for us both to write a song for The Karate Kid soundtrack.

Andy and I worked in a very random kind of way for the next 20 years and it was a different kind of narrative. The second-half narrative would have been about how you get on when you really sort of don’t get on. And Andy’s alcoholism became worse and worse. By the end of that period, we were not on speaking terms. He was really ruined by drink at that point. But I didn’t want to write anything that was unkind about him. I tried as much as possible to be as generous as I could up to 1984. After that point, it would have been quite difficult.

In the context of us both doing other things, his primary activity was to work as a record producer. That’s what he wanted to focus on. I primarily worked in production. So, we didn’t see each other very much at all, except when we came together to make the Shrinkwrapped and Mall albums in the ‘90s. Afterwards, we’d go away to our own lives. So, it was very, very different.

Gang of Four’s music has been considered profound stuff addressed with academic rigor by many. My sense is you wanted to infuse the book with a sense of the levity that also informed the group’s existence.

Gang of Four has always been a really fierce live act. I know people sometimes think it’s a project architected to support the words. It isn’t. It’s not like Patti Smith or Leonard Cohen, whose work is all about their words.

Although I wrote all the words, the band is a really fun, loud rock band. I guess it’s a guitar band. Gang of Four reflects our collective love of Funkadelic, Jim Hendrix, Led Zeppelin, and of course, punk rock.

I think there’s always been an anti-intellectualism in Britain and America in which if you have ideas about things, somehow it makes the work hard to understand. I don’t think that’s true at all. I don’t think our music is hard to understand.

Going back to our discussion about how things can be changed by culture and art, I feel if musicians keep writing songs about club life, getting laid, and getting wasted, that we will limp into fascism without a whimper. I’m not a politician, but I think about how people like Bob Marley did a huge amount of good for things and supported the idea of getting on with each other within a pop reggae context.

The book covers the famous incidents involving the BBC banning “At Home He’s a Tourist” and “I Love a Man In a Uniform.” You’ve said it’s a net positive when things get banned because it means power structures are being challenged. What impact do you feel Gang of Four had in encouraging others to challenge power?

All I know is many musicians have taken stuff from what we’ve done, and it has encouraged them to do their own thing. That goes for everyone from Nirvana to Run the Jewels to Frank Ocean. There’s a bragging side to hip-hop and a consumerist side to it. But Run the Jewels talks about what’s going on. I say that advisedly, because one of my great inspirations was “What’s Going On?” by Marvin Gaye. It was great to dance to and listen to. It was really powerful.

I know authors are unreliable witnesses of their own work, but I do know what people have said to me about Gang of Four’s music.

There’s a quote from Frederick Douglass that says, “Power concedes nothing without a demand.” And that’s it.

You have a chapter on the influence of The Velvet Underground in the book. Brian Eno once said, "The first Velvet Underground album only sold 10,000 copies, but everyone who bought it formed a band." Do you think a similar statement could be made about the Entertainment! LP?

That’s what I’m told. During the last tour, it was amazing that Rich Robinson from The Black Crowes, Peter Buck and Mike Mills from R.E.M., and Lenny Kaye came up and did guest spots. They were all talking about why they were there and how they wanted to do it because it meant something to them. Jason Falkner, who’s St. Vincent’s guitarist, came up to me and said, “I just wanted to say how much I love what you did.” He wanted to guest with us, but St. Vincent was playing a set at the same time as us during a festival. I’m really flattered by these things.

Certainly, we sold about as many records as Velvet Underground, but I think we always had a problem with commerciality. Would it have been better if we had written more commercial music? I actually thought I’d written a commercial song with “I Love a Man in a Uniform.” I didn’t start off trying to write a commercial song, but once it was in the can, I thought, “This sounds like it could be a hit.” And everybody said it could be, too, until it was banned. It wasn’t the tune itself, which I wrote. It wasn’t the chords Andy wrote, the beat Hugo wrote, or the bassline Dave wrote. Rather, it was the words. That shows it had relevance and power, enough to be prohibited. If we had been chasing money, Entertainment! would never have been made. It’s an outsider record. I mean, it’s funny that it even exists, I think sometimes.

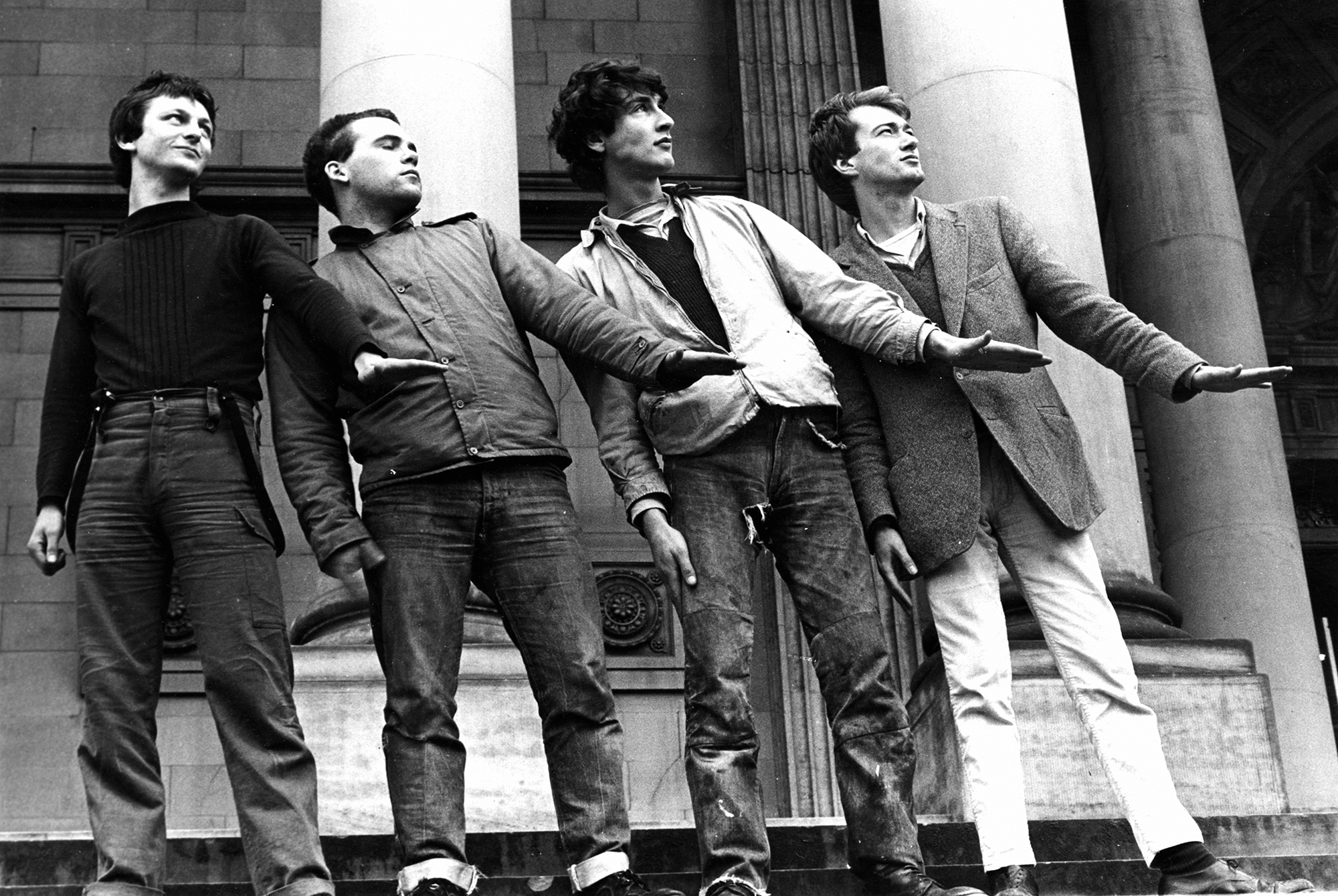

Gang of Four, 1979: Dave Allen, Hugo Burnham, Jon King, and Andy Gill | Photo: Andy Corrigan

Gang of Four, 1979: Dave Allen, Hugo Burnham, Jon King, and Andy Gill | Photo: Andy Corrigan

In the “Gang of Four V1.0” chapter, you talk about the genesis of the group’s earliest songs. Elaborate on the creative process amongst the four of you that yielded them.

We’d been given, free of charge, a room in a big old warehouse in Leeds. We had all the equipment set up in there. What would typically happen is me, Dave, and Hugo would turn up. Dave and Hugo would sit around and play stuff together. I’d sing along a bit and then Andy would turn up. After a while, it was about trying to find a very simple riff or beat that we could work with.

“At Home He's a Tourist” was something we thought would be great as a disco song, because we all liked Chic and things like that. Dave could play that stuff. Hugo played a four-on-the-floor beat. And then Andy improvised around it like Jimi Hendrix, which was so inspirational. And then I did my thing on top of it. So, it was very layered.

I can’t think of any situation in Gang of Four where we were like Lennon and McCartney, Burt Bacharach and Hal David, or Holland-Dozier-Holland, who were wonderful writers who could just knock out a hit. That was really a function of the way Andy I worked. Andy didn’t do any work outside the studio whatsoever. He didn’t even have a guitar in his flat. So, he would turn up and work.

I wrote lyrics and still do in a note format. And then they become this great lottery bag in which you put your hand in and pull out a sentence or a line and it then has its own dynamic. So, that was really the way it worked.

I felt once you realize what the logic of the song was, you then had to follow its scent. So, say I’ve written something about how everything we have is often at the price of someone else’s misfortune, as we discussed earlier. I’m talking about people in prosperous countries. For “Ether,” I first wrote “Trapped in heaven lifestyle” and then the motif became this thing about Northern Ireland, because the British army had been found guilty of torture at this detention center called Long Kesh that was used to house Irish nationalist prisoners. As I mention in the book, it involved sensory deprivation, noise, and wall-standing. The song ended up having its own logic to it.

How do you look back at Mall and Shrinkwrapped?

The only song we performed from those records on the last tour was “I Parade Myself” from Shrinkwrapped. It was a song I wrote and it’s much better live than it is on the recording. It’s like a metal song built on a vamp. It has grit. That’s the thing, I think.

We made those records in Andy’s studio, and I don’t really like working with samplers and those things. I like being with other musicians and working together. But Andy didn’t like that. I missed having a real drummer.

This was the persistent musical difference between us. I missed the fluidity and the grit of playing with other people. I wanted to work with a band to write the songs and then take that band into the studio to record them. But Andy didn’t want to do that. I’m not going to be snarky about him, but he said, “I’m a control freak.” That’s what he said about the way he worked. And that’s why his album with Red Hot Chili Peppers went south. They wanted to be a band, but he had them playing to drum machines.

I’m a huge fan of Brian Wilson’s work. I listen very often to the greatest love song ever written, which is “God Only Knows” by The Beach Boys from Pet Sounds. If you listen to it, it feels like it’s from another era. It’s like Beethoven. How was he able to write a song that goes along with no real chorus to it? It does have a time signature change. And then it sparks up into a different key. After that, there’s a sort of improvised run out. I don’t think that sort of thing happens when you’re using GarageBand.

There’s a terrible creative corruption from digital technology, which I do use. But as soon as you do, you’re thinking, “Oh, I need to have an idea. I need a beat.” And then the application says, “What kind of beat do you want? Do you want a bossa nova beat? What time do you want it to be in? Do you want a bassline?” And then everything sounds acceptable. But who wants to make acceptable music?

Yes, everything sounds nice, but the palette becomes really anonymous if you surrender to that stuff. So, for Mall and Shrinkwrapped, I felt after each record was made that they had some potentially really great songs, but they sounded quite sterile to me at the end. That also goes for the Hard album. I hated Hard. I loathed it. We had booked the drummer from Miami Sound Machine. He came in and laid down the tracks. And then they were all replaced with the drum machine. And that wasn’t the deal I signed up for.

I can’t say any more than that. I went along with all of this for a long time. I don’t think any of these are great records.

Gang of Four, 2011: Mark Heaney, Jon King, Andy Gill, and Thomas McNiece | Photo: Tom Sheehan

Gang of Four, 2011: Mark Heaney, Jon King, Andy Gill, and Thomas McNiece | Photo: Tom Sheehan

I felt Gang of Four’s 2011 Content album was very much a return to form. What are your thoughts on it?

That one was different. For Content, we did work really hard to make that a good record. But I found it very difficult to create. By that point, my songwriting role was to write all the melody lines, vocal parts, and lyrics. And then Andy did everything else. Although I really like that record and it has some really strong ideas, I think it would have been better if we had a bass player and drummer in the room and worked together to take those songs to different places.

When we were working, I’d sit there in the middle of two days just listening to a hi-hat pattern. Eventually, I’d just leave. I don’t like working like that at all. I’d rather not be in a room with people chopping up a drum part to find a perfect take and then splicing it everywhere. That’s not how The Beach Boys’ “Good Vibrations,” Marvin Gaye’s “What’s Going On,” or anything by Nirvana or even Run the Jewels was done.

I like the messiness of the creative process, even though the machines get easier all the time.

Elaborate on the irreconcilable differences that occurred after Content, resulting in you and Gill never working together again.

It was his alcoholism. That’s probably why one in every four shows was a disaster when we played. It was really difficult. Anyone who has worked with someone who has substance abuse and alcohol addiction problems knows how difficult it is.

I wanted us to stop. I didn’t quit the band. I said, “Our band is you and me. There has to be two of us." But we weren’t on speaking terms. It was so toxic. It’s not unknown for guitarists and singers to not really get on with each other.

It’s terribly difficult to be in the same room with someone when they have all of these physical and psychological behaviors that are not nice. So, I wanted to pack it in. Oasis wouldn’t have continued with just Liam Gallagher. And The Smiths stopped when Morrissey and Johnny Marr split up. So, I said, “Carry on, but don’t call it Gang of Four.”

Going back to your earlier question about writing a new Gang of Four album, that wasn’t something I was going to do. I think it’s wrong to make solo records and call them Gang of Four. Andy couldn’t write lyrics to save his life. And I’m a very, very bad guitarist. You’ll never hear me play a guitar on a record. Andy was a wonderful guitarist. So, I think people should stay in their lane.

Along with new music, you’ve said you’re going to focus on creating new visual art going forward. Tell me about what you’re pursuing in those realms.

I did the covers for Entertainment!, Solid Gold, Songs of the Free, and the associated singles. I always wanted to be an artist. I didn’t really want to be a musician. So, I was always really thrilled by the reaction to the artwork.

The cover of Entertainment! has become an iconic thing. It has a very simple storytelling device, which I obviously ripped off from the Situationst idea, with the Cowboy and Indian scarecrow visuals and the narrative around them. It had a great power to it.

At the merch stand on the final tour, I was selling copies of my “Coins” piece, which was originally used on a Gang of Four compilation album called A Brief History of the 20th Century. That was something I was very pleased about. It had two coins: a French Franc coin that had the old national slogan on it that translates into “Liberty, Equality, Fraternity.” And then there’s a coin from the time when the Vichy government during World War II were Nazi collaborators. So, they changed the national slogan on that coin, which translates into “Work, Family, Country.”

We’re seeing that shift right now in the great battle of ideas happening in the United States. “Liberty, Equality, Fraternity” are the great founding principles of the U.S. constitution. The people who say, “Work, Family, Country” probably don’t believe in any of those things. As we discussed earlier, I’m using culture to describe that great battle.

So, it’s art along these lines what I’m working on. But I can’t describe that I’m going to do before I do it. It’s bad luck. But there are a lot of things I’m working on in that territory.

When I worked on the Gang of Four 77-81 box set from 2021, I did the design for it. I was delighted to have it be nominated for a Grammy. So, I think there’s a great deal of room for visual art to do something that’s more interesting.

The music I’m working on is about how we live now and what we’re enduring. I think it’s interesting. It’s about the absence of meaning, today. I think it’s why the Gen Z lot discovered Entertainment!

I don’t know if the music will be released under my name. If I was working with David Pajo on it, it would be a collaboration and wouldn’t be a solo album. I intend to work with other people. I think that will make it much better.

Describe the creative drive and spirit that inhabits and informs you today.

When I started off, all I wanted to do was change the world. I’m now in the twilight of my existence and I still think the world needs to change. I think that the creative urge is to make a difference. I want to make ripples in the pond of life and in the pond of culture. I want it to be thrilling, exciting, and fun. I think the world right now is changing, but not in the way I would applaud.

So, you either suck it up and say, “Oh, you know, let’s just wait and see.” Or you do something. We see what happens when we sit on our hands—and that’s what’s happening everywhere. You can see what’s going on in Gaza. That’s the result of us sitting on our hands as we see this terrible nightmare. So, we can’t sit on our hands. That is not an option.

Watch the video podcast version of the interview: