Donate to Innerviews

Since 1994, Innerviews has provided uncompromising, in-depth interviews with musicians across every genre imaginable. And it does that with no trackers, cookies, clickbait, or advertising.

Your donations are welcome to help continue its mission of highlighting incredible music and artists, without any commercial considerations.

Your contributions will be instantly transformed into stories and videos, and cover hosting and web management costs. Importantly, your dollars will help ensure Innerviews remains absolutely free to all visitors, independent of their ability to financially support it.

Please consider making a donation today by using the PayPal QR code below.

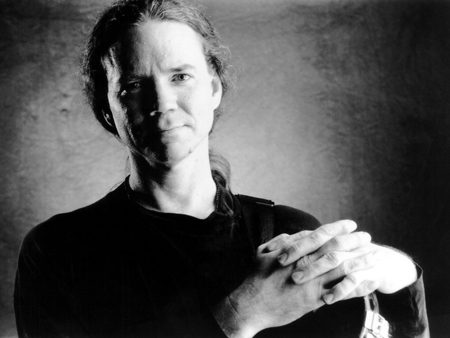

Michael Hedges

Finding Flow

by Anil Prasad

Copyright © 1994 Anil Prasad.

Orderly lines of apples, carrots, pea pods, and other organic produce fill the tables. Gleaming bottles of spring water reflect the dim yellow lights as the enticing aroma of fresh-squeezed juices fills the air. “Fresh enzymes, man, gotta have ‘em!” declares guitarist Michael Hedges, the proprietor of the traveling health food stand.

The backstage area of Toronto’s Danforth Music Hall is the stand’s home for the evening. Hedges is decked out in swirling, psychedelic sweatpants and a bright yellow tank top. His frizzy mane of shoulder-length hair is tied back in a ponytail. He’s in the middle of whipping up an apple-and-greens cocktail on his portable juicer. He quaffs down the beverage and quietly begins closing down shop, for he’s due on stage in mere minutes to serve up a different kind of refreshment. Its ingredients include quirky, witty songs and eclectic acoustic guitar stylings seasoned with flute and keyboards—his recipe for audience enthrallment.

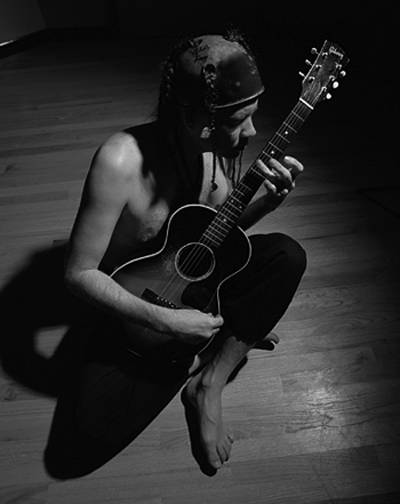

Slapping and tapping, strumming and snapping, Hedges hits the stage and engages the crowd with his one-of-a-kind fingerstyle guitar techniques. It’s an astonishingly original approach that incorporates alternate tunings, harmonics and striking the guitar’s body and strings with his fingers, palms and knuckles. That Hedges often manages to play such intricate, avant-folk pieces while singing, dancing and spinning around barefoot makes his performances even more remarkable.

It’s memories like these that linger in the minds of friends and fans that knew Hedges, who died in an automobile accident in 1997 at age 43. Though he was revered for his solo guitar work, Hedges chose to pursue a new direction for 1994’s Road to Return. The singer-songwriter record found the Oklahoma-born musician merging his guitar playing and bright, airy vocals with a more produced, pop-oriented sound. Its full slate of percussion and synthesizer accompaniment was a radical departure from previous albums comprised largely of solo guitar and vocals, with occasional additional instrumentation.

Hedges remains best known for 1984’s Aerial Boundaries. The groundbreaking instrumental album showcased his revolutionary technique which finds his left hand tapping notes while the right hand picks the remaining strings. Initially, many musicians and listeners alike believed they were hearing guitar duets. They were often stunned when they realized it was Hedges performing solo with no overdubs.

At the time of this interview, conducted backstage prior to the Toronto gig, the guitar remained a core element of Hedges’ existence, but his musical outlook was now integrated into a spiritual philosophy based on the principles of Chi Kung. The influence of those teachings was evident in most of Road to Return’s lyrics and his choice of words during this discussion.

Many feel Road to Return represents a departure for you, but I understand you see it differently.

Let’s look at the difference between my first album Breakfast in the Field and Aerial Boundaries. Breakfast in the Field was me trying to be as nice to my label Windham Hill as I could be. I wanted to be exactly what they had to offer, which was acoustic guitar. So I used two microphones and did it straight. Aerial Boundaries was my record. The compositions were more developed and I did some ensemble work and electronic stuff on it. By the time that was purged out of me, I had a bunch of songs left, so I did them with just guitar and vocals on Watching My Life Go By. Then I had been touring so much that I developed a lot of cover tunes. So, I put out a live record. After that, I became interested in different textures, so I started on Taproot. It was very textural with flute, acoustic guitar, electric guitar, some synthesizers, and a little percussion. It expanded texturally with not so much solo guitar. Road to Return is an extension of that. There are more textures and of course, it’s all vocals. So to me, it’s a line of things. It doesn’t seem like anything is departing. It seems like things are evolving.

I wanted to do some arranging for my songs instead of just doing them with guitar and vocals or keyboard and vocals. I wanted to further develop them to include more instrumentation that suited them well. And now the stuff I’m writing is even more textural. Stepping back from the guitar endears me to it. I like it more than ever. But I was getting a little tired of playing acoustic guitar all the time. I’ve always played keyboards and flute. Now, I’m finding my voice—literally. I’m finding my singing voice, my keyboard expression and my flute expression. So, Road to Return is everything I can play. Plus I engineered it. So it all seems very solo, although the textures are very varied.

What did you learn about yourself when making Road to Return?

I learned I have my attachments. When you start talking to people on a spiritual path, pretty soon you start coming to attachments. What are you attached to? What dogma is it that’s blocking your energy? To me, total freedom is being free of attachments. Am I attached to solo guitar? Am I attached to tonalities? Am I attached to a style? What is it that’s got a girdle on my spirit? And I think part of it was having another engineer in the studio. There was something about having another presence there that was blocking me. It doesn’t mean that’s not right. I feel I should be able to work with an engineer. But I wanted to experiment a lot in the studio. That’s the reason I did it myself. I wanted to goof off. I wanted to try fun things and do it all on my own. And I didn’t want to become attached to that either, you see? So, it can work all around you and you can fool yourself into thinking you are free, but what is total freedom? That’s the question.

What were the seeds of your spiritual awakening?

I think it has to do with turning 40, having my father pass on, and watching my children grow up. You go around that magic year 40 and you see that your life really is becoming a beginning. You can see forward, but you can see backward quite a ways. I think when that happens, you find out that you are a spirit. It can happen anytime, of course. People get it whenever. But for me, it just happened. I don’t know what it is. It’s a new energy coming through. This seems to be what’s guiding me—my spiritual path, rather than a guitar path. In other words, when I’m thinking about expression now, I think I’m free of the guitar and being free of the guitar will enable me to play the guitar better. So I’m just as concerned with making my body more flexible because that will improve my sense of rhythm. I’m more interested in yoga now than writing fingerpicking guitar solos. The other thing is that I’ve already written a lot of fingerpicking guitar solos. I’d like to try other things. It doesn’t mean I’m putting it away permanently. Lucky for me, I was able to put it away before I got sick of it. Now, I can look at it in a much more complete way.

This has been going on ever since I started music—all my life. To me, it seems like a seamless thing. And now it’s worked its way into my meaning. For awhile, it was guitar. It was just guitar. And I became known as a guitarist. My agent still thinks I’m a guitarist because that’s what people come to see: “Michael Hedges the guitarist.” Well, when you get pigeonholed for so long, you start to think “Gee, I really can do this thing.” I won the Guitar Player magazine “Best Steel-String Acoustic Guitar Player” award five years in a row. So, they put me in the “Gallery of the Greats.” Pretty soon, you think “Yeah! I can do this.” And then you look at other things and you think “Hey! This looks like fun. I think I’ll learn how to scuba dive.” [laughs] And then when you scuba dive, you see the same things start to fall into place like when you learned how to play guitar. Or when you learn how to sew and then everything is like sewing. And then everything is like everything else. So, to the best of my knowledge, learning how to appreciate modern art is having an effect on my guitar playing. Even though the guitar isn’t in my hands, I’m learning how to play better guitar by going to the art gallery—by not being attached to the guitar all the time. It’s enriching my soul and the soul can flow into the guitar. That’s the way I think about it.

Describe the elements of your spiritual path.

It involves no dogma, you see. To me, it is freedom. What is freedom? To me, freedom is what will allow your spirit to expand and grow or gain consciousness. It’s a consciousness expansion. It involves no set pattern. It’s not Christian or Buddhist or anything that can be labeled. It’s the same problem as when you try to categorize music. How can you classify a person’s spiritual path? You can say what influenced it, but you can’t define it as it’s happening. The definition comes after it’s happened. I’m not a member of any organization. I have teachers and this is important to me. I started studying with a Chinese master who taught me Chi Kung. “Chi” is energy. “Kung” is exercise. That’s how simple it is—energy and exercise. You study Chi Kung and you’re presented with ways to enable your energy to flow throughout your body.

There’s some other forms. You could study Aikido or Kung Fu or Ju Jitsu or Tae Kwon Do or any of these dances that go on in these fighting forms. But that’s like saying “I play Country and Western or New Age.” What my teacher does is explain the compositional journey and then you go and are free to do whatever you want to. So I apply Chi Kung to my guitar playing and musicianship. It doesn’t mean that I’m following any particular kind of exercise. It’s an awareness that my teacher has given me for energy and he does that with direct transmission. When you’re in a room with this guy, you just get it. [laughs] It’s really beyond words. It’s just an awareness you get throughout your body. Some people would call this feeling “the spirit of the Lord.” They’d say Jesus Christ gave this to them. And if I was into the Christian form of Chi Kung, I would say that. You feel something in yourself and call it that. But to me, it’s more sacred and personal.

You’re practically beaming when you talk about this stuff.

[laughs] Well, that’s the real telling thing, isn’t it? How peaceful have you become? Lucky for me, I knew I was fucked up. People would look at me and say “There’s Michael. He’s going through something.” I was lucky enough to find out that I wasn’t the big man I thought I was. It’s nothing specific. Let’s say it was a release of the ego. You look at yourself and you’re not necessarily happy with maybe the way you manipulate people or the way you cling to attachments such as power or money. I think I saw myself attached to things and not knowing how to get out of those attachments. My marriage breaking up happened simultaneously, so I found I needed to change. If that’s what fucked up is, that’s what I was. Then you start to do things about it and this is mirrored in the music. To me, the concept of Road to Return was returning to your true self or personal self. That’s what all religions talk about too—finding that God self or finding God within you. That’s what the Road to Return means. You see, I don’t like to preach. I like to work in symbols. That’s my way. That’s why I am just as much an instrumentalist as I am a vocalist. I like to say things without words. My songs on Road to Return, of course, have words and are descriptive, but they’re kind of symbolic too in that the symbols form that meaning which I can’t really express. So, the Road to Return is a symbol for inner expansion. The lyrics in the song “Road to Return” say “The more reflection, the more I see.” So, Road to Return could also mean looking back, not in a nostalgic way, but perhaps in a reflective way.

You’ve said “Opening my hips is directly related to what’s going on in my compositions.” Elaborate on that.

A direct example of what was happening to me comes from when I was a kid in the second grade. I wasn’t real athletic. I was a little bit timid, but I still tried out for Little League and the 100-yard dash. And my coach motioned me over, pointed to my feet and said I had a slight pronation. I didn’t know what a pronation was! It’s like the opposite of a pigeon-toe— you have a little bit of a turn-out. This guy told me as a second grader that I would never be a runner. What does that do to a little guy? My coach probably didn’t know any better. He didn’t realize he was instilling an idea in a little kid. Okay, so 30 years later, I start taking yoga and I’m stretching out and I feel this incredible tightness in my legs. I realize that all my life I felt my feet were a little big and not quite right. I had a thing about my feet. So I was at my yoga lesson and my teacher said I had wonderful feet and I swear to God man, I thought I was gonna start bawling right there— you know, like something was released. Some blockage went away and that fear was gone.

The energy started happening through my feet and I could connect up with the Earth better. Different massage therapy people talk about muscle memory. You stretch in yoga and you get to that place in your hips where you can actually feel all that old stuff starting to flow. And you get the instrument in your hands and that flow translates through the music. That’s what soul is in music. It’s your soul coming into the music. And if your hips, shoulders, neck, or whatever start to open up, you have that much more of a flow that you can charge up into the music. So working on my body is the best thing I can do for my music. If I have to put off writing for six months, big deal. I don’t care. I’m working on writing as I’m running down the road or working out.

We’re surrounded by some interesting items here in your room backstage.

You see it all around right now. There’s the juicer. There’s a portable inversion swing over there. I’ve got my library of videotapes of my yoga teacher that I watch on a little personal VCR. They have all my lessons. I’m studying with dancers. I’m taking belly dance lessons. I’m studying a little bit of ballet. We had a dancer on the road with us for several gigs. So that’s my current thing. Once my body gets flexible enough to start working it, I’ll go on to something else. But at this point, it’s given me a new burst.

You recently became a motorcycling enthusiast.

I love motorcycles. It’s about focus. You gotta focus on the road. I have a new motorcycle song called “Sapphire.” Sapphire drives a pink sportster. She’s got red hair.

How would you respond to a devil’s advocate who suggests the spiritual trip and the motorcycles are part of a midlife crisis?

Could be. I don’t care. But I don’t think so because I’ve always wanted to ride a motorcycle and now I feel I can. My dad wouldn’t let me have a motorcycle. If I had a midlife crisis, I’m sure getting out of it. I think that a midlife crisis is good because it gives you an opportunity to deal with things that have held you back from becoming self-actualized. If that’s what I’m having, I’m gonna embrace it, rather than freak out.

Describe the average day in your life when you’re not recording or on tour.

I just try to get through the day without getting bored. The trick is finding something that will allow my growth to happen. It’s mostly a search for higher consciousness. I try not to take that responsibility too lightly. If I’m not on tour, I don’t have anything to do. I could make a record, but it took me four years to get this one together. So what was I doing, you know? I was just looking for something. Road to Return is a sketch of what I was looking for. I’ve been thinking “What does this mean? Why am I here?” I think that’s how a lot of music gets written. Some people sit around and can think “How am I going to pick up women?” Look at MTV with all these guys lookin’ good. Look at all this country stuff. I saw this country video and the whole thing was close-ups of this guy’s face. He’s thinkin’ “I look so good.” [laughs] How much fun is that gonna be for that guy when he gets older? What’s going to happen to him when he has his midlife crisis? What’s invested that he can grab hold of? That’s when nostalgia comes in and you live in the past.

“Sister Soul” from Road to Return explores the idea of getting in touch with one’s feminine side. What inspired it?

For awhile, I didn’t know what I was doing. Around '87-'88, I was wearing all these funny clothes. I’d go shopping in women’s stores and all my wardrobe seemed to be pink. I’d wear a pink jacket or really tight pants. I couldn’t figure out why. What is this? Why do I want to wear makeup? It was a funny thing I went through. Maybe I wanted to be a rock star or something like all of those guys who were getting dolled up. Then I thought “Well, this is just my natural femininity coming out.” When I was writing “Sister Soul,” I came to terms with it. I thought “This is who I am. I don’t need to dress funny or look funny. I’m just going to be my feminine side.” People talk about this all the time. It’s a current fad. All these men are trying to get in touch with their feminine side. But I tried to make it a little more symbolic in “Sister Soul.”

There was a time when I would even dress up in drag just to figure out who I would look like if I was a woman. I was dating this woman who was an actress and we had a really good time together. She showed up at one of my gigs dressed up as someone else and completely fooled me. So I thought I’d dress up as a woman once when I was going to pick her up at the airport. She recognized me immediately. [laughs] I thought I did a pretty good job. I fooled my brother. She taught me about makeup and we worked on walking. But it didn’t have so much to do with dressing up as a woman. It had to do with learning how to act—learning how to let go of your personality. I think people tend to play up the sexual thing because that raises eyebrows. But to me, it was just about being somebody else—letting go of the attachment to your personality and mannerisms. It’s what actors do when they’re acting. So “Sister Soul” just grew out of that somewhere.

“Communicate” has another positive message that seems particularly appropriate given the political turmoil in the world.

I’m blissfully ignorant in the political arena, but I hope anything I come up with that’s peaceful in my heart will be transmitted. Let’s learn to communicate. If we learn to communicate, we won’t have this. Let’s attack the problem right at the source, rather than what’s going on now in order to figure out why these people can’t get together. If you learn to communicate with yourself and not fool yourself, you won’t have as many problems communicating what you really feel with other people. If you start this germ on that level, it will mushroom into some kind of world awareness or peacefulness.

With “Communicate,” I also wanted to try a song that was more rock and roll. I’ve always liked rock and roll so much, but I’ve always been kinda shy and never had a band. I would tell a lot of people I was going to make a rock record and hope that I would. [laughs] I’d tell everybody. And then Road to Return turned out to get kind of a life of its own. There are some things on it that are headed towards rock. “Communicate” is more like '60s rock. “Follow Through” is a little more rhythm and blues. “India” was more like Peter Gabriel, but a little bit heavier.

The audience reaction to your keyboard-based tunes is more subdued than the applause that greets your solo guitar pieces. What do you make of that?

I’m not interested in any fan who puts technique over content. To me, my new keyboard tunes have a deeper meaning and they don’t demand applause. Applause isn’t what I’m after. Communication is what I’m after. So I’ll lose some of my fans, but I would rather lose them than keep away the ones that are after the deeper meaning. It’s not that my guitar solos don’t have deeper meaning. It’s not that I can’t write things that are technically flourishing and have meaning. In fact, I do have some new guitar solos, but they’re different. They’re played with a pick. One is called “Jitterboogie” and the other is called “Dirge.”

Why is using a pick attractive to you at this point in your career?

Because I can do long, loud strums. I played that way on “Silent Anticipations” and “Ritual Dance,” but I had never written a ballad with a pick, so I thought I’d write one. I had never written a boogie, so I wrote a boogie. The trick is to find something new. If it’s something I can have flourish as a technical thing, that’s okay, but I don’t need to wow anybody anymore. I would rather make love to them.

Website:

Michael Hedges