Donate to Innerviews

Since 1994, Innerviews has provided uncompromising, in-depth interviews with musicians across every genre imaginable. And it does that with no trackers, cookies, clickbait, or advertising.

Your donations are welcome to help continue its mission of highlighting incredible music and artists, without any commercial considerations.

Your contributions will be instantly transformed into stories and videos, and cover hosting and web management costs. Importantly, your dollars will help ensure Innerviews remains absolutely free to all visitors, independent of their ability to financially support it.

Please consider making a donation today by using the PayPal QR code below.

Jonas Hellborg

Uniting Nations

by Anil Prasad

Copyright © 2023 Anil Prasad.

Photo: John Sargent

Photo: John Sargent

Defying preconceptions is a natural state of mind for Swedish bassist and composer Jonas Hellborg. Since the dawn of his career in 1981, he’s operated with a fiercely independent mindset and remains entirely driven to record, release, and perform music strictly according to his instincts. His complete antipathy towards industry-dictated practices and priorities has informed his 22-album solo catalog. It’s a diverse and ambitious body of work that explores the realms of jazz, fusion, funk, metal, free improvisation, Indian classical music, and solo electric bass.

Hellborg just released The Concert of Europe, his first recording in nine years, on his own Bardo Records label. It’s a trio album with the late Ginger Baker and Bernie Worrell that captures the telepathic communication the musicians established across years of working together during the ‘80s. Recorded in 1987, it’s often propulsive and dynamic, and full of intricate interplay, deep grooves, and even an orchestral tint resulting from Worrell’s immersive keyboard work.

The emergence of The Concert of Europe represents Hellborg’s reentry into the music industry after taking a step back from the complete disarray and economic decimation for artists that’s occurred across the streaming era. Hellborg hasn’t felt the need to be part of the desperate scramble musicians face today. They’re increasingly told to release tracks every few weeks or months to feed the social media-driven content machine, regardless of whether or not their muse has the capacity for it.

Rather, Hellborg remains resolutely focused on the act of making music, rather than the complexity of releasing and monetizing it. He’s been able to adhere to those principles because he successfully invested the money he made from his prolific ‘80s and ‘90s output, enabling him to pursue total artistic freedom.

His last effort prior to The Concert of Europe was 2014’s The Jazz Raj, recorded with his group Art Metal, featuring Mattias Ia Eklundh and Ranjit Barot. It’s an inspired blend of pulsing jazz-rock, distortion-driven guitar and bass, and kinetic drumming. It continued Hellborg’s exploration of Indian music that began in earnest as part of Mahavishnu, the second edition of John McLaughlin’s legendary fusion group that existed between 1984-1986. Hellborg further developed the integration of Indian elements across solo projects involving the likes of Selvaganesh, Shawn Lane, V. Umamahesh, and V. Umashankar on albums such as 2002’s Icon and 2005’s Kali’s Son.

Hellborg has contributed to several other recent recordings between The Jazz Raj and The Concert of Europe. He appears on two efforts from progressive rock luminary Devin Townsend: 2022’s Lightwork and 2021’s The Puzzle. Exit North, the atmospheric rock quartet featuring Thomas Feiner, Steve Jansen, Ulf Jansson, and Charlie Storm, included Hellborg on its 2021 single, “Let Their Hearts Desire.” He can also be heard as a performer and producer on singer-songwriter Ana Patan’s 2021 album Spice, Gold, and Tales Untold.

Hellborg conducted several interview sessions with Innerviews across 2022-2023, resulting in this career-spanning exploration.

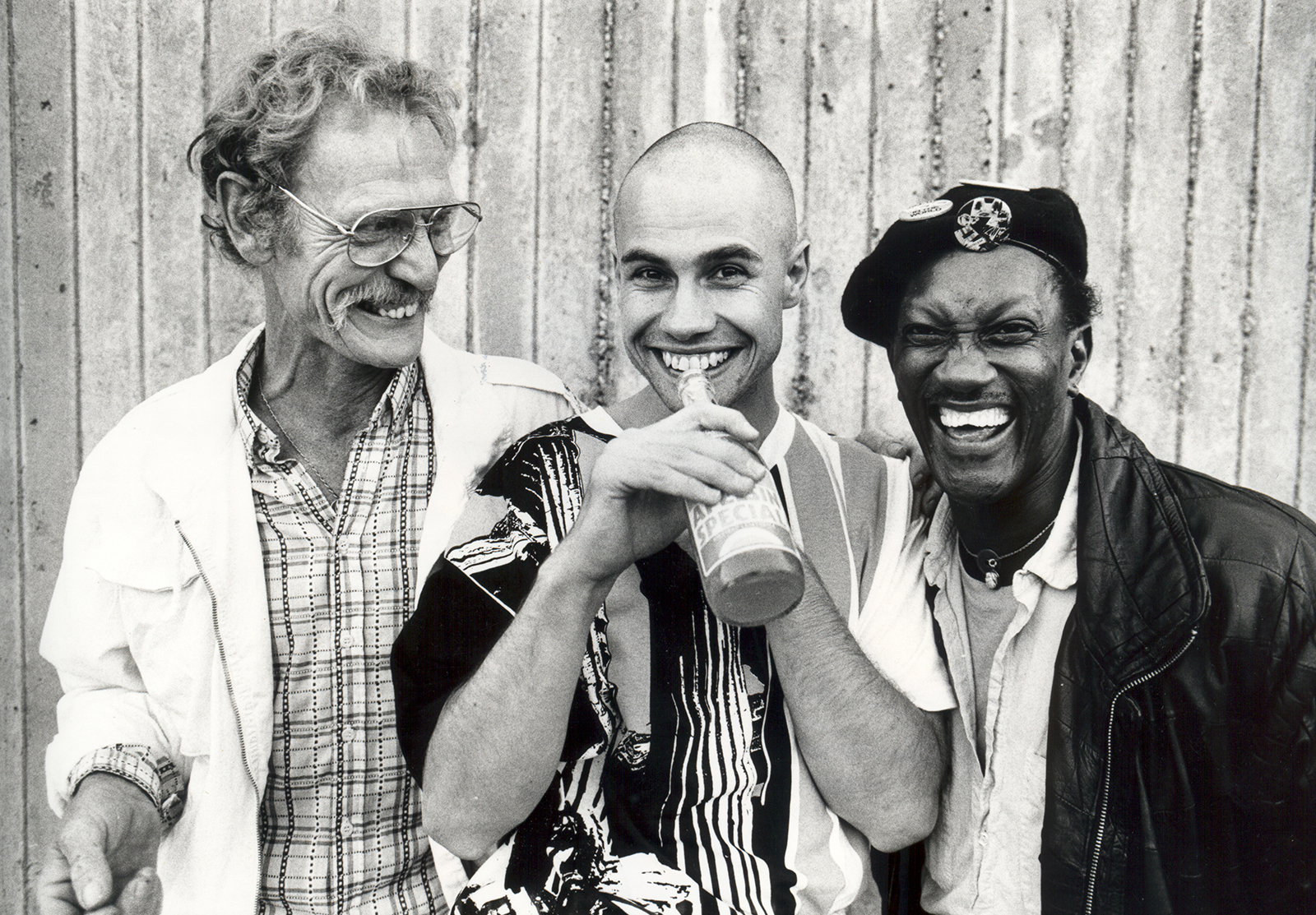

Ginger Baker, Jonas Hellborg, and Bernie Worrell: Lund, Sweden, 1987 | Photo: Albert Wiking

Ginger Baker, Jonas Hellborg, and Bernie Worrell: Lund, Sweden, 1987 | Photo: Albert Wiking

Discuss the origins of The Concert of Europe.

We did three or four tours together of Europe. I also recorded a lot with Bernie before those tours. When we toured with me, Ginger, and Bernie, we did very long improvisations and pieces, just like I continued doing later with Shawn Lane and Jeff Sipe. It’s what I’ve always been into in terms of when I go on stage and play. And that’s what we did in the studio as well for this album.

Initially, it was just me and Ginger. We went into Marcus Music, a studio in London, after doing a duet in July 1987 at the Bracknell Jazz Festival. I had a friend who worked at the studio, and we booked three days there. We went in and played and recorded whatever came out. Then I brought the tapes back to my studio in Sweden, and then Bernie came over and overdubbed on keyboards.

When we did these recordings, I was very stuck in the idea of records being productions that involved a lot of manipulation to whatever you recorded. Then, it wasn’t about just recording something and it being what it is I had a lot of paranoia about if stuff was good enough. So, this recording kind of just got forgotten. One day, I listened to it again and realized “Oh, this is wonderful stuff, just as it is.”

The interplay we had together was special. Ginger and I managed to communicate and be fluent. You really hear the uniqueness of his drumming. I don’t know of anybody who ever played like Ginger. It was very well recorded, so I mixed it and put it together. I kept listening to it for a long time before I decided “Okay, this is a record.” And that’s pretty much it.

This recording is about people playing together. It’s not about people sitting in their bedrooms with a computer, laying down tracks, and sending them to a friend who then puts something on top of it and sends it back. That is not music. I don't know what that is, actually, but it cannot compare to people actually working together. It’s as simple as that.

Calling it The Concert of Europe is a play on words. On one hand, with this trio, we played a lot of concerts in Europe. On the other, it was a group of three very strong personalities from different backgrounds. You need an agreed-upon power balance to make a group like this reach its potential. In political terms, this is what is lacking in today’s world. The Concert of Europe is an attempt to unite nations.

What does the recording reveal about yourself as a musician in the late ‘80s?

When I look back at that period, I regret not allowing myself to be more of what I actually was, rather than trying to doctor everything after, and being paranoid about my own abilities. I was trying to live up to some kind of preconceived idea of what I was going to play like or present. What we did spontaneously was interesting and nice, and I should have appreciated that more.

Ginger Baker and Jonas Hellborg perform at the Copenhagen Jazz Festival, 1987 | Photo: Jan Persson

Ginger Baker and Jonas Hellborg perform at the Copenhagen Jazz Festival, 1987 | Photo: Jan Persson

Both Baker and Worrell are no longer with us. Reflect on your relationships with them.

I think what’s significant about both of them is the very normal human relationships we had. We were very close on a personal level. When we toured, there was no bravado, egocentricity, or self-importance. We had a very nice time, and we were good friends.

Bernie was free of the ideas of prestige and prejudice. He was such a spontaneous reactor to whatever you gave him, and he would dive in. Whether he had the physical capacity to do it or not, he would just go for it and try. He was also a very kind human being. This matters because that is how he played. He was very capable, but did not have an overblown ego. He possessed this very rare ability to immediately recognize what was being played—some people call it perfect pitch—and react to it with creative answers. He was not bound by certain stylistic ideas. He was known as the funk keyboardist, but that never got in the way of him hearing a musical idea.

Bernie was orchestral in his playing. He was unconventional in the way he reacted to musical input, which is important to state. Today, there is very mechanical behavior in music. A given musical idea will often result in a predictable response from just about anybody, leading to absurd ideas about what is right or wrong music. Bernie was a free thinker. A true progressive.

Ginger was one of the most misunderstood musicians ever because people believe he was very mean, angry, and grumpy. But he was actually very nice. It’s just that he didn’t tolerate stupidity. He was very nice to anybody who had no misconceptions about what one should be or do. He was very friendly to farmers, bricklayers, car mechanics, and people who were not in the music industry. That was very much reflected in our touring situation in which everyone was very normal, simple, spontaneous, and straightforward. It was a very pleasant adventure.

I think pop-stardom environments caused Ginger to try and live up to what people expected him to be. When he was around show business people, he had another persona for them. Most of the time, I think he just wanted to be left alone.

When it comes to music, there was equal confusion. He considered himself a jazz drummer. But in a sense, he was not about the delivery of American jazz legends. He modeled himself on the British drummer Phil Seamen. He was also very much into African drumming. But classic rock fans simply viewed him as one of the iconic rock drummers.

Ginger was very interesting in that he didn’t play patterns. Rather, he played musical phrases. He had a fluid creativity and he listened. He could fit that approach into any music he was involved in. If you played something, he heard it and threw it right back at you. He wasn’t a conventional drummer. He wasn’t about just playing a beat or keeping a groove like most people who play drums that think, “That’s what I have to do.” For Ginger, music was about constant development. It was about a flow, and he was listening all the time. He was involved in the music and would not let it stagnate. It would always progress.

We continuously developed together, and unfortunately, a lot of stuff didn’t get documented. It was just what happened in the moment. It was about what people at the concerts experienced, and then it was over and gone forever.

How did you connect with Baker and Worrell, initially?

It was through Bill Laswell. My first meeting with Bill happened during the same time I had my first US gig with Mahavishnu in 1985. That’s when he invited me to play on Public Image Ltd’s Album. Ginger and Tony Williams both played on that record, and that’s when I asked Bill to get Ginger’s contact information. I called him up and that was it. We started playing together. He came to a concert in Copenhagen I had booked, and we played there. We got along really well and enjoyed each other’s company.

Bill also set me up with a whole crew to record my 1986 album Axis, which included Bernie, Bernard Fowler, Anton Fier, and the engineer Bob Musso. Bernie and I became friends and he went on to play live with me, including the trio tours with Ginger.

Jonas Hellborg working on The Concert of Europe analog multitracks at Bardo Music Studios, Markneukirchen, Germany | Photo: Ana Patan

Jonas Hellborg working on The Concert of Europe analog multitracks at Bardo Music Studios, Markneukirchen, Germany | Photo: Ana Patan

The new album is currently only available on CD, but I understand you hope to eventually do a high-quality vinyl pressing which you feel will be the best way to hear it. Tell me why you believe vinyl remains an important medium.

I would love to do vinyl, but it would have to be done correctly. Most of the operators of cutting rooms and pressing plants today lack critical knowledge on how to make records, plus the capacity at all plants have been booked up, so there are long waiting times. This is particularly true for the few companies that have the knowledge. Eventually, vinyl will happen for this recording.

Most vinyl is cut from bloody computers. I cannot see the point of cutting a vinyl record from a digital file. It makes no sense, because you compound the disadvantages of digital with the disadvantages of vinyl.

I’m even looking at the possibility of setting up my own cutting room and pressing plant to do it correctly. If nobody’s going to do it properly, maybe it’s something I need to make happen. Of course, I wouldn’t be the only person involved in running it. I’d need to have partners and investors. I do know people who do excellent work, particularly mastering engineers that have been shoved out of the business by hipsters with beards who don’t know what they’re doing, but now own most of the machines. So, the knowledge is out there. We just have to bring it all together.

I’m absolutely convinced about the superiority of analog sound over digital sound. If you want to duplicate analog sound, vinyl records are the only way to do it. Cassettes could also be an option, but cassettes have so often been made from crappy stuff. I have some made by Sony from the ‘90s that had ceramic enclosures and high-quality tape with great stability and perfect sound that wasn’t much worse than a quarter-inch master tape. So, that could be an option if it still existed as a possibility. But vinyl does exist. It has a market and there are record players out there. So, vinyl is a viable option.

The majority of your catalog exists only on CD, in addition to some limited digital releases. Have you been unsatisfied with those options for the last 40 years?

Definitely. It is what it is. Digital has some advantages over analog and vice-versa, but I prefer analog sound. If a recording has been made in the analog world and you dump it to digital, you definitely lose aspects of the sound. I’ve done tests at home, because I have extremely good analog equipment. I have a 1" 2-track tape machine I mix sound to. I took master tapes and transferred them to the best digital format with a 384 khz sampling frequency and the highest bitrate, and I could still hear the loss of depth and space in the sound. It just sounds flat. There’s such a difference. It’s not even comparable. Yes, with vinyl, you get some noise and crackling from the vinyl itself, but the basic sound remains.

I have been talking to companies that do digital releases, like The Orchard, which is one of the big aggregators. But all they do is dump your music into the digital wasteland and it never becomes anything real. The same is true for Bandcamp. I don’t think I’ll ever go that way. It’s also morally wrong to release music this way.

I see this as a struggle between reality and virtuality. The streaming of music over different platforms only serves to relegate music to the background. There is nothing to be gained from having music on Spotify. Forget about the economic situation for a moment. There is no dignity in it.

I simply see a slow rebuilding of playing concerts and distributing physical media as the sensible path to take. it will not be huge, but there is hope of survival with that strategy.

And this idea that records are merchandise is also wrong. First of all, I do not want to be a seller of t-shirts and coffee mugs. I play music. If someone wants to hear what I play, they will do so through concerts and the recordings I release. And the recordings are supposed to be listened to, not just exist as material representations that sit on a shelf.

I always say to myself, “Why am I releasing music? I’m not a business. I’m making music for the sake of making music.” That’s what I enjoy. If I end up in a situation in which I realize, “Oh well, nobody will hear this music,” then too bad. But I made the music. When an opportunity to distribute the music emerges in a good way, then I’ll pursue it. In the meantime, I’ll work on trying to initiate a change and a coming together of people who have similar interests to create a better way of making music available.

Jonas Hellborg recording at Bardo Music Studios | Photo: Ana Patan

Jonas Hellborg recording at Bardo Music Studios | Photo: Ana Patan

Bandcamp was once considered an honorable digital distributor. But it has now changed hands twice and is currently owned by Songtradr, which just fired half its staff. Its future is unclear. I understand you and Michael Shrieve have an idea for a more artist-driven concept for digital music distribution.

Our consensus is “If we don’t do it, who the hell will?” It’s all about how you manage the forces that drive this somewhere it can be realized. Objectively, it is not bloody rocket science what Bandcamp does. It’s pretty simple to do. In fact, for a little more than two decades, I’ve run my own web shop, and although there have been some ups and downs, it has been worthwhile.

The most problematic aspect of creating a platform today is defending yourself against hackers and criminal organizations who want to destroy it. Other than that, having a server that hosts a bunch of music and has a payment system is straightforward.

Another issue is when people put these systems together, they often believe “We have to be the biggest platform in the world. We have to reach 100 million people.” No. You just need somewhere you can put up some music and where people who are interested can come and get it.

I admit, I dislike the idea of “supporting” musicians. It’s not fucking begging. It’s not a case of, “Oh, I’m a musician and you must support me, otherwise I will go under.” No. The statement should be, “Music fulfils a function in the listener’s life and therefore there is a transaction that happens in which there is a mutual benefit.”

When I went to buy a record as a kid, I didn’t think about needing to support somebody. I thought “I want this music. I want to put it on my turntable, listen to it, and have it make me happy.” That’s all it is. Do you want to hear my music? If so, are you willing to pay the cost to have it? If their answer is yes, good.

As you know, most people are no longer willing to pay for music. The current perspective among the majority of listeners is “I am willing to pay for a streaming service.” The idea of paying the artist doesn’t even enter their minds.

Well, then I say, good riddance. I don’t have to be paid if I don’t fulfill a social function in real society. Sometimes, I think I should be doing something else with this change in mindset.

The truth is the reality of the music industry is not driven by people who create the music, the record labels, or the venues. Rather, it’s driven by the consumption of the public. If you think about the ‘60s, what happened is a lot of people would go to clubs to see shows and then buy records. They were amassing these records as they related to the emergence of record players, and then cassette players. That’s what drove things.

Then some shady characters understood “Oh, there’s money to be made here,” and then they organized everything around that. Then you had musicians fulfilling the desires of the business community as they related to the people who wanted to buy music. They stepped in and took over.

Now, people have shifted from sitting around the record player to using mobile phones and computers, and messing around with apps. The social reality is no more. But there are still people who listen to music seriously and are passionate about it, but there’s no significant way of actually connecting with those people directly in a serious way. The ways that do exist are limited.

The thing about buying a record is that it’s a proper commercial transaction involving humans who can be enthusiastic about getting something and listening to it.

So, the idea is basic, which is to set up an artist-run web platform that is honorably run. The other would be to set up a pressing plant run by artists for artists, as we discussed. But we cannot do these things on our own. I’m willing to set it into motion, but other people need to join in, or this cannot become reality. I invite people to reach out to me through my website and Facebook to discuss how they could get involved.

When Bandcamp was acquired, a lot of people felt betrayed. The founders claimed they were not in it for a large-scale payout. A community of musicians and even journalists like me rallied around them to propagate the idea that it was a “platform for the people.” And at the end of the day, all we did was create yet another large-scale transaction that enabled a handful of people to get very rich. And what was left is a platform that barely evolves and decreases in credibility with each passing moment.

If you’re the person who started Bandcamp and someone dangles money in front of you that is so enormous, you cannot resist the temptation. You cannot stick to your values, because you think, “Oh my God, all that money.” I’m not saying you cannot blame someone for doing that, because you can. Either you have moral depth or you don’t. But human beings are rarely very moral, ethical, or strong.

Jonas Hellborg performs at Leverkusen Jazztage, Germany, 2015 | Photo: Klemens Möllenbeck, KMG Design

Jonas Hellborg performs at Leverkusen Jazztage, Germany, 2015 | Photo: Klemens Möllenbeck, KMG Design

In 2004, you told me “In principle, I think all music should be free. But if you contribute to the world, you should also have the benefit of that world.” And here we are in 2023, and for all intents and purposes music is free, unfortunately without the latter component.

In the early 2000s, I thought “The future of the music business may actually involve giving away music for free and having it supported by advertising. The advertising will ensure musicians get paid and you don’t have to sell it anymore.” I was looking at the technical advantages of the Internet at that time. And then Napster came on the scene and gave away the music for free anyway. And the streaming companies keep all the advertising money and don’t share it with the musicians.

A big part of the problem is the inability of musicians to organize properly. The rights organizations are also to blame in that they didn’t take care of things when they should have. Politicians and parliaments around the world should have stopped it from happening.

I’ve asked rights organizations in Sweden where I live, “What the fuck? What are you doing? There are thousands upon thousands of videos on YouTube with me in them and I’m getting paid €20 a year from them. With the enormous amount of plays these videos get, I should be getting much more, but you are not covering it. I have all my music registered with your organization, but you have no system that can track or control what is on YouTube. You cannot go into it and check ‘This was written by this person and the person who put up the video doesn’t own rights to it.’” It’s unbelievable.

The fact is tech companies move exponentially faster than governments or rights organizations. They routinely unleash technologies globally without any consultation and society is left to sort out the aftermath for years or decades. The ubiquitous launch of public AI platforms is another example of a dramatically impactful technology launched without any oversight.

Right. Exactly. These platforms say, “We have no responsibility. It’s whoever uses our platform that should be responsible for reporting problems or paying people.” This is ridiculous, of course. The people making money are the people who own the platforms. They should police and control them. But they don’t. No-one is making them do anything. So, they get to do whatever the hell they want.

Another problem is that we live in a world without universal boundaries. So, we have situations in which different countries have different copyright setups, which leads to music being policed differently. That means when a piece of music is posted to a platform, different rights organizations and laws are involved, leaving a giant mess. How do you come to terms with it? The platforms have left this mess up to everyone else. Again, they don’t take any responsibility.

As a musician, your only option is to stop complaining about things like Spotify and just take your music off it. Don't allow streaming.

The Orchard is a problem now. In the past, they had the option of opting out of services you didn’t want to work with. When I first tried using The Orchard, I disconnected Spotify from it. But then they took that option away and distributed the music to every streaming service. So, I can’t get off any of them if I use it.

So far, the only one that has worked for me is Apple’s iTunes store, which still exists. It was good while Apple was focused on downloading. People would actually buy albums. But now, Apple emphasizes Apple Music streaming. The whole thing is ridiculous. There’s little out there that supports musicians.

Is the state of the business the biggest reason for you not releasing new music for nine years?

That’s the majority of the situation. I have been recording throughout those years. I have 10-15 records in the can that I could release. But I don’t feel a need to get those out quickly, because again, the purpose of making music for me is the music. So, I record it and then I say, “That’s good. I’m happy with that.” I may also say, “Oh my god, that’s not very good.” But I have my relationship with the recordings, and I have them. I can listen to them anytime.

Of course, it would be nice to get them out, but the investment is just too big for me, and it doesn’t pay for itself. The infrastructure of selling records collapsed. I cannot make a record and just give it away for free. It’s too much hassle for no return.

From a personal perspective, luckily for me, I’ve ended up in a situation in which I’m not dependent on making a living anymore. I made enough investments at the beginning of my career when I was doing very well. I started my own label back in 1984 and I was actually getting paid properly for every record that was sold, rather than an artist royalty of 60 cents an album. I built up my financial safety net and now I can consider myself retired if I want to. By that, I mean, I don’t think of music as being work.

I’ll make music regardless of whether I’m getting paid or not. But the hurdle to get music distributed satisfactorily is so steep.

Jonas Hellborg live at Museo Della Musica, Venice, Italy, 2022 | Photo: Marco Celegon

Jonas Hellborg live at Museo Della Musica, Venice, Italy, 2022 | Photo: Marco Celegon

What are some of the unreleased albums?

I have a couple of things I did with Keith Leblanc and Aydın Esen. I’ve also got two-or-three more records with Ginger I haven’t released. There are also many records I could put out with Shawn Lane. There is also music I’ve recorded with classical ensembles. They’re all sitting there on the shelf.

I will be releasing an album in the near future that I did with Selvaganesh. It’s a record we’ve had in mind for at least 10 years. We’ve even toured some of this music, mainly in Asia. Selva came to visit me in Sweden in December 2022, and we recorded straight to tape. Now that he is done touring with Shakti, I’ll be working to get this record released properly.

I’d like to name some albums from across your career and have you give me the first thoughts that come to your mind. Let’s start with The Bassic Thing (1981).

That’s my first attempt to do something and the start of my story. It was my entry into the international music world. Previously, I was playing with groups in Sweden and was very unhappy about that. Those groups didn’t go anywhere, and it was kind of miserable.

I was going to give up on a career in music, but then I started doing my little solo bass thing. I did some concerts, almost by accident. I managed to also get a gig on a radio show playing three songs. I sent the tape of that performance to the Montreux Jazz Festival and suddenly I was invited to come out there and play. When I performed, I was heard by a bunch of different people. Among them was Michael Brecker who took me around to be introduced to everybody and that’s what eventually led to my gig with John McLaughlin.

So, I decided to record The Bassic Thing and put it out through a label called Amigo. When I asked if they’d release it, they said “It’s a very big investment to release a record and we don’t know if it’s going to sell or not. If you print the records and give them to us, we will distribute them for you, and you will get this much money per record.”

I did that and it immediately sold 1,000 copies, which more than paid for the costs. I even made some money on it. It was an important step in my life.

I think the album is good for what it was at the time. Nobody did anything like that back then. It was the first solo electric bass album, but that phrase didn’t even exist at the time. It was also the record that connected me with Bill Laswell. He heard it and then told Michael Shrieve about it. That’s how I became connected with both of them.

Mahavishnu’s Adventures in Radioland (1986).

It was a peculiar event in terms of recording it. We did it in Italy and it was the victim of the overproduction craze people were involved in at the time. It was done very, very piecemeal, put together bit by bit and overdubbing. The album has synth sounds of the era and Simmons electric drums. It’s kind of questionable, but some of it’s pretty good.

I was in Italy for a month without doing much during the sessions, which wasn’t that bad. There was great food and it was a great hang. [laughs]

Public Image Ltd’s Album (1986).

I look at that positively for the connections that came out of it, more than what it is or what I did on it. Getting exposed to Tony Williams and Ginger Baker, the two drummers on it, was very important. The particular aesthetic of the drum sound that was used came out of The Power Station and also had a lot to do with the engineer, Jason Corsaro.

I was so impressed with the sonics of it all, but more than anything, the way Ginger played and the uniqueness of his drumming. As the producer, Bill Laswell understood Ginger’s drumming and how it would fit the music. Other people have tried to do records with Ginger never understanding what he actually does. He doesn’t fit into a formula. It was so important for me to observe Ginger during the sessions.

I don’t think my own contribution was incredibly important. I did some stuff and it worked well, but I cannot claim any ownership of the music. It’s a great record and the bringing together of people on it is fantastic.

Ginger Baker’s Middle Passage (1990).

That was done in Martin Bisi’s Brooklyn studio—at least the stuff I was on. I had a lot of new toys at the time, including a Wechter acoustic bass and a Wal MIDI bass, which was one of the first of its kind. We did some interesting stuff on it and it’s a very well-constructed record. It was a case of Ginger being the lead musician and we layered everything else on top of it. I like it a lot. A very good record.

Niels & The New York Street Percussionists’ self-titled album (1990).

That was something I tried that didn’t really work out. I was trying to help out Niels Jensen and he wasn’t very cooperative, and it didn’t turn out how either of us had hoped. He had something totally different in mind.

Niels was a Swedish teenage idol. He was a friend and a conceptually interesting artist. He had lots of great lyrical ideas, but he wasn’t much of a singer. But I tried to create something around him. We did our best.

The record wasn’t even supposed to have that name. The record company that released it gave it that title.

Jonas Hellborg in concert at Leverkusen Jazztage, Germany, 2015 | Photo: Klemens Möllenbeck, KMG Design

Jonas Hellborg in concert at Leverkusen Jazztage, Germany, 2015 | Photo: Klemens Möllenbeck, KMG Design

The Word (1991).

That is one of my favorite things I’ve done. Just the opportunity to play with Tony Williams and have him perform on my music was unforgettable. And what we did was quite amazing.

I had made some demos of the music. I’d play them to Tony. He would listen, take notes, and we would then play. I would play acoustic bass together with him in real time. He nailed it every time. The whole record is one or two takes.

Working with Tony came out of discussions between me and Bill Laswell, the producer of the record. I told him I’ve always wanted to play with Tony. I showed Bill my ideas and he made it happen.

Initially, I wanted to have a string orchestra on this record. That’s what the arrangements were made for, but we could not afford one. So, we overdubbed the string parts to make them sound bigger.

Material’s Hallucination Engine (1994).

That was done when Bill Laswell and I had Greenpoint Studios up and running. We crossed paths many times in the studio. One day, he was playing some of this stuff and one of the tracks was “Cucumber Slumber.” Bill asked me if I would play on it, so I did. I also did “Naima” with Bernie Worrell, which is a song I’ve always liked a lot and played many, many versions of. It’s a really great record. I’m very happy and proud to be on it.

Greenpoint Studios happened because I had moved to New York City during that period. I had a whole recording studio in storage that I brought over with me. I suggested to Bill we create this studio because he was paying lots of money to other studios all over New York. So, we looked for a space and found one in Greenpoint, New York and set it up. We had a lot to do with each other during the ‘90s and it had a great deal of impact on what I did and how I did it.

Friends Across Boundaries with Sultan Khan and Fazal Quereshi (1999).

That was a wonderful experience. It was the first time I went to India. I was invited by Fazal to play some concerts. He had already been to Sweden to play with me before that.

When I arrived in India, all the concerts had been canceled. Just like that, from one day to the next. Fazal said “Don’t worry, this happens in India. That’s how it is. Instead, I have a recording session set up for us.”

So, we got together, and I spent time with Sultan Khan, which was great. I learned a lot about North Indian music from him in that week—more than I’ve learned from anybody else. Previously, my main exposure to Indian music was South Indian music. I’m so happy to have had the opportunity to connect with him. It was so beneficial, educational, and inspiring. You learn a lot from the social interaction you have with people who play music. It goes beyond what you learn from listening. You understand things about the music which are not expressible in words. You realize how they approach certain ways of playing and how they explain the music.

This session took me further into music than I had ever been before. I think we made a good record.

Herman Kathan's Busch-Werk’s Trance (2011).

I had just moved back to Europe. I was in Germany, and Herman contacted me to tour with very nice, enthusiastic people. The musicians had been into my music for a long time. They’re playing a very specific type of music focused on African drumming. They also do workshops and bring African drummers to participate. I had a small part in the concerts. I did my solo thing and then we did some nice stuff together, including some duets. It was a good way to get out on the road and this recording came out of that.

Art Metal’s The Jazz Raj (2014).

My regret with that is I couldn’t get Mattias la Eklundh to actually come into the studio and record with me. He insisted on overdubbing and controlling everything too much, but I like the record.

It took my involvement with Indian music a step further, because we used raags that are very unconventional in the West. The note content is very unorthodox if you are not Indian. I tried to translate them into Western sensibilities, melodics, and harmonics.

I felt the album reflected an interesting continuum of bringing in distortion into the Indian context. I thought it was a really cool record, despite it not all being done in a real-time live situation.

Unfortunately, the album fell under the radar and wasn’t heard by many people, which is a shame.

Photo: Warwick GmbH

Photo: Warwick GmbH

What’s your perspective on the value of music to civilization at this moment in time?

I think the question relates to the definition of music, which I think has gone out the window. People do not understand music any longer. This seems like an odd thing to say, but there is a difference between something and the description of it. Most people have lived with music as the description of music, rather than the music itself.

A musician may say “I’m going to make a record” or “I’m going to play a concert.” But often, they don’t think about the music first. It shouldn’t be about the idea of playing that music because I would like people to hear it. Rather, I want to be the person who plays the concert because I want to, not because I want someone to appreciate it.

This becomes a discussion of the musician’s hierarchical position in society. Look at Bach, Beethoven, or Mozart. What they did involved another reality of music. They had similar problems as today, but not on the scale we face. Bach had to write music for church services. But he was also writing music all the time. He was constantly putting it down on paper and inventing. He was going, going, going all the time. It was about the music, not fame or glory.

Now, look at Joseph Haydn. He was about the glory. He became a big celebrity and made lots of money. The same holds true for Handel. He was one of Bach’s contemporaries and he was also in England writing music for the Royals and being very celebrated. But Bach was just this guy who had a school and was working in the church playing organ and writing pieces. Of course, he was trying to make business out of this and hoping to get paid. But that didn’t stop him from writing. And Beethoven couldn’t even hear at the end of his life, but he was still writing and obsessed with music.

Today, on the creator side, we have people who are not obsessed with music. They are obsessed with who they are perceived to be by society, which is an absurdity. And then you have another problem, which is people that make music because they cater to an audience that is so bloody retro. These musicians focus on stuff that has already been done previously. They’re looking backwards. What I want out of music when I hear it is the reaction of, “Oh my god. What is that? I have never heard anything like that before.”

This idea that “I want to be the new James Brown, Beatles, or Jimi Hendrix” is about your place in society. It’s about wanting to be admired and egocentricity. It’s not about the magic of discovery of sound and how you interact with it. On both the side of the creator and listener, they’re going, “Oh, this is so nice. It’s what I was listening to in the ‘60s.”

I was listening to some Miles Davis concerts from the early ‘70s recently and it’s so beautiful and fucked up. It’s so uncoordinated and chaotic, but you can hear there is this desire to search for the unknown.

So, the question is how can we play music today without playing what we have already played? How do you create the awareness or a desire to pursue something new—unknown note combinations, emotions, or visions?

One of my guiding principles as a musician is that I am not the creator, rather I am the discoverer. Music is already there. It’s not something I can create, but I can discover what can be done with it. I can consider what can be found and how it can sound. But it’s not my invention. It’s there for everybody. I am strictly talking about music. When you start bringing in terms like creation or ownership, it all becomes problematic.

Today, music is all about definitions. People ask questions such as, “Can you play that part? Can you play over that change? Can you do this? Can you do that?” Okay, fine. You can do those things and you have a description, but where is the music?

Look at John Coltrane. He really blazed the trail for what I’m talking about. He had the capacity to play changes with the most advanced scales, but where did he end up? With A Love Supreme, and working with Eric Dolphy and Rashied Ali. He was about exploring for discovery. That’s what I want to do. Whether or not people know my music is not important for me. I’m interested in the question “Can I experience something new?”

During the last 10 years, I’ve been playing solo concerts mainly in Germany. I might get 30-40 people in the audience, but it’s great. It’s totally improvised music. I’m going in new directions and trying to explore. There’s a small bunch of people there who really want to be there and appreciate it. They’re really into it and give it their full attention. It doesn’t matter if it’s good or bad music. That doesn’t have any significance, because it’s an adventure. It’s an occasion to be in a state of mind together in which no-one has to judge. The audience just walks out of there afterwards. It won’t be recorded. It was what it was. But people do leave happy, and they thank me and say, “It was wonderful.” And that’s because it was a real journey.