Donate to Innerviews

Since 1994, Innerviews has provided uncompromising, in-depth interviews with musicians across every genre imaginable. And it does that with no trackers, cookies, clickbait, or advertising.

Your donations are welcome to help continue its mission of highlighting incredible music and artists, without any commercial considerations.

Your contributions will be instantly transformed into stories and videos, and cover hosting and web management costs. Importantly, your dollars will help ensure Innerviews remains absolutely free to all visitors, independent of their ability to financially support it.

Please consider making a donation today by using the PayPal QR code below.

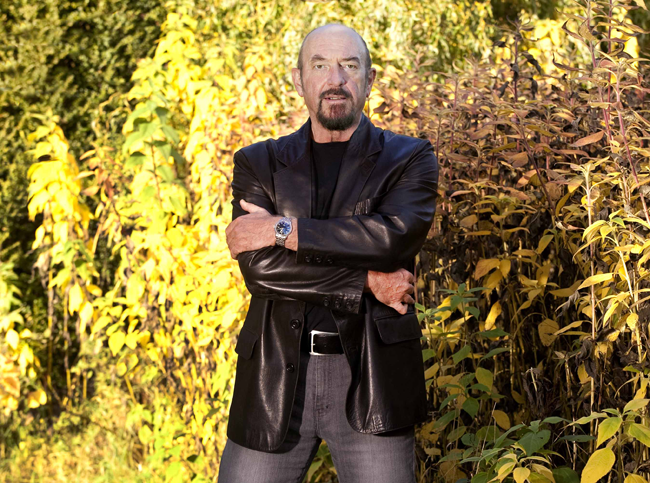

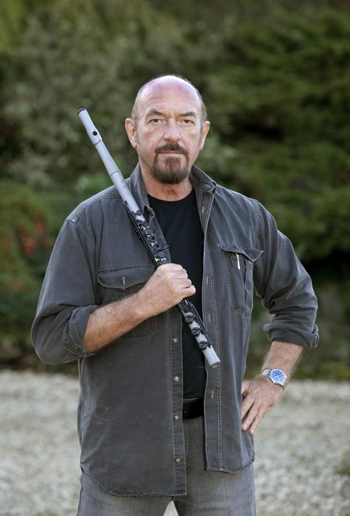

Ian Anderson

Changing Realities

by Anil Prasad

Copyright © 2000 Anil Prasad.

The adage says respect is earned. In the entertainment business, that phrase is often taken literally. Whether it’s the ranting of a cutthroat industry participant or the headlines blared at consumers from the cover of Entertainment Weekly, respect is too often the sum of an equation made up of SoundScan charts, box office receipts and bestseller lists. But when the tides of fashion erode those numbers, that respect can quickly transform into scorn and apathy.

As the leader, frontman and flautist of the pioneering British progressive folk-rock act Jethro Tull, Ian Anderson is responsible for more than 60 million records sold worldwide. And he’s acutely familiar with the just-described scenario. It’s been more than 13 years since Crest of a Knave, the group’s last bona fide hit album. To say Tull is considered passé by the music business these days is an understatement. But it’s of little concern to Anderson. Thirty years after forming, the group maintains a devoted, global fan base that regularly fills 5,000-12,000-seat theatres and sheds. And record sales, though they’ve waned, remain stable.

The fact is, Tull continues to persevere and prosper, despite adverse industry conditions. Its unique combination of heady rock dosed with folk, world music and orchestral elements continues to evolve as evidenced on 1999’s J-Tull.com and 1995’s Roots to Branches. By maintaining a core musical focus, Anderson continues bucking the trend of his contemporaries by refusing to let Tull become an oldies act. That resolve extends to his ever-emerging solo career too.

The Secret Language of Birds, Anderson’s third and latest release as a solo artist, represents a more individual statement than his recent Tull work. It offers a subtle, approachable blend of folk and world music leanings, but doesn’t share the group’s heavier rock influences. Rather, it veers toward a more meditative direction with its personal, reflective lyrics and a decidedly rootsy, organic vibe.

Will The Secret Language of Birds reach an audience beyond Anderson’s faithful flock? That remains to be seen. But during his last concert tour, British avant-rocker Joe Jackson—no stranger to the ravages of criticism himself—was heard quipping "Believe it or not, I recently saw a DJ at a trendy New York nightclub playing Jethro Tull records. These days, it seems the more un-hip something is, the more hip it becomes."

Contrast the differences in approach between The Secret Language of Birds and your last solo album Divinities.

Divinities was a very specific album commissioned by EMI’s classical music division. I somewhat reluctantly went into it because I hadn’t written an instrumental album before—certainly not one with such a great emphasis on the flute and orchestral instruments. I was a little nervous about doing it. I decided to make it a thematic or concept album if you will—one that took a respectful and somewhat personal view of some world religions and the cultures and societies that spawn them. I tried in a fairly lighthearted way to illustrate something about the way that religion works in that environment—the way that I see it. Being instrumental, it’s necessarily somewhat abstracted, so it doesn’t get too literal or offend anybody. It’s quite different from the new album which is very deliberately a set of individual songs that are designed to stand alone. They don’t refer to each other in any way.

The interesting thing about writing relatively short songs is that you focus on one idea at a time. You can do it in a disjointed way. You don’t have to sit and conceptualize it in one hit. The Secret Language of Birds was written and recorded over a period of a year in between Jethro Tull tour gaps. The Divinities album was really mostly written and recorded in a very finite period of time—one song after the other, one piece after the other. It was rather more demanding as you had to see the project through almost as if it was one piece of music. Working on short songs is a little more relaxed. You do them in isolation and they live their own lives and you can pick them up and put them down one at a time. It’s a little easier to put an album together that way.

I understand you feel The Secret Language of Birds has more female appeal than most of your previous work.

In the last couple of decades, Jethro Tull has concentrated on being a democratic rock band. There’s been more upbeat, up tempo music designed to involve all of the members of the band all the time. Doing a solo album with acoustic music was really about shrugging off the responsibility of having to make the drummer happy or having to include big electric guitar riffs. It was an opportunity to do stuff that’s a bit more selfish, a bit more introverted, more personal lyrically, a little more intimate and one-to-one. Like a lot of people, I’m more comfortable one-to-one with someone of the opposite sex than I am with someone of the same sex. So, I think the solo album might appeal more to the female fans of Jethro Tull than most of our rock kind of albums. I know I’ve said it’s an album for the girls and the J-Tull.com album was for the boys, but that’s kind of being a little crude and sweeping. There’s an element of truth in there though. I’d say The Secret Language of Birds would probably also work for the kind of guys who like to shave their legs or slip into something soft and sexy from the Victoria’s Secret catalog on the weekend when they do the yard work. So, we’re not entirely excluding them. [laughs]

Several tracks on The Secret Language of Birds and Divinities combine multiple world musics with European influences. Where does your fascination with merging so many varied traditions stem from?

I think it comes from just having traveled a lot. And even before traveling around a lot, my childhood did embrace a number of different musical influences from big band jazz to rock and roll to folk music to church music to pop music. So, once I did start moving around as a professional musician, I encountered musical forms from all sorts of different places. I’m just open to suggestions. But I’m not open to Hawaiian music, country and western, bluegrass and Caribbean steel drum music. There’s just some things my ears say "No thank you" to and I just can’t accommodate them. They don’t work for me. But there are a whole bunch of other things that do intrigue me. The sounds, mechanics and structures intrigue me. Sometimes it’s the actual instruments that intrigue me because they are ergonomically interesting. It’s interesting to try and pick up a strange instrument and figure out where your fingers are supposed to go and how to make the instrument talk to you. So, it’s a love affair with different sounds and elements. The fact that they may come from different places and times means there’s a danger that you might end up with something so eclectic, so mixed up and so complicated that it’s a bit of a mess. It’s that which I have to apologize for during the last 30-odd years. [laughs]

What ideas do you keep in mind when combining these diverse influences?

When I do get it right, it’s a subtle blend of herbs, spices and delicate culinary gestures that come together to produce something that really has a life of its own. I think of myself really as a chef in the kitchen who chooses the ingredients that work well together. I’m not a chef and I’m not working in a kitchen, but I imagine it would be a little bit the same. There are some things that just aren’t going to work together. They’re not going to work from a taste or texture point of view. Some things just won’t make it on the same plate. And that as a musician is the lesson you have to learn when you take different elements from different places. Sometimes some head banging goes on and those influences fight each other—they don’t enhance or complement one another. You only learn from trial and error. I have committed both trial and error and occasionally been hung, drawn and quartered for it. Probably quite rightly so. But I continue to persevere and doubtless will make more mistakes and carry out a few more errors of judgment during whatever career is left to me. [laughs]

How sensitive are you to the critical lashing you’ve experienced?

I am interested in my failures and that’s why I will say to the record company "Don’t send me the good reviews, just send me the bad ones." [laughs] The goods ones are nice to have, but I don’t need a pat on the head after all this time. I don’t need someone telling me what a clever boy I am. I don’t need to feel good to get up on stage or get on an airplane to get to the next show. What I do need to know is the negative stuff. I need the criticism. I need the dressing down. I need the pointed finger. It’s important to hear what people have to say on a negative level even though it can make you feel pretty bad sometimes. Happily, that doesn’t happen too often. The record company thinks I’m crazy because they believe I’m the only artist on the planet that wants to read the bad reviews. They say "Oh no, I think you’ve got it the wrong way around. You mean you just want the good reviews." And I say "No, no, no. I want the bad reviews." I like to be told what I’m doing wrong. [laughs]

Both The Secret Language of Birds and Divinities have spiritual underpinnings. Tell me about your viewpoint on that realm.

On most Jethro Tull albums, there’s usually something that touches upon spirituality. It’s part of my life. I’m not a religious person, but I think of myself as having a concern with spirituality. I think of myself as someone day-to-day who has a moment or an hour of relatively detached thinking about more aesthetic or grander aspects of life. It’s hard not to do when the front page on England’s most popular daily newspaper today is devoted to Prince Charles relating his views on spirituality and his grave concerns with scientific development, particularly in regards to genetic manipulation and cloning. Some of us are confronted by these things on a more regular basis. I’m probably not as potty about it as Prince Charles, but I do take an interest because of my reading and interest in a number of things.

Spirituality is something that comes up every day of my life, but I don’t go to church to experience it. I walk past a lot of churches. [laughs] I don’t go in very many of them. I have a great respect and appreciation for the value of such edifices of human endeavor, hope, belief and faith, but I’m not one who is drawn to worship alongside other people. But I would feel very sad if a day had gone by without my spending a moment or an hour—or any point in between—with a fairly dedicated mind towards things on a loftier plane. It’s just part of the balance of day-to-day life. I must do a little bit of that—just like I quite like to do a couple of hours of seriously loud music. I like to sit down and eat a couple of times. I might enjoy just being a couch potato watching CNN for a half-hour, soaking up the day’s events. So, there are some moments in the day when I get pretty serious about things and other moments when I like to laugh a lot, poke fun at people or have fun poked at me. My ideal day is spread across a number of different levels of intensity and intellectual demand.

You were gravely ill in 1996 with an acute blood clot. How did that experience affect your perspective on spirituality?

Ultimately, not very much. I think most of us when threatened by something find reserves within ourselves we didn’t know we had. So, we become more resilient and robust. I wouldn’t want that to be confused with bravery because I don’t think I have that particular strength or capacity. There is a kind of resignation that says "What’s going to happen is going to happen." You have to buckle down to doing what you can to overcome any setback in your life, but at the same time, you have to come to terms with the reality that this might be it. I don’t want to exaggerate about this. In my case, it was a short-lived period of time—a few days of real concern. The miracle of modern drugs eventually sorted out the problem in a few days. It took a couple of weeks for me to get the go-ahead to safely travel. I don’t have that problem anymore. But it’s something that does affect you. It makes you feel vulnerable. It makes you face up to your own very finite mortality.

When these things happen to whatever degree of severity, I think in a sense it prepares us for a longer-term scenario when something like that happens and it really is the end. I don’t dwell on it, but I think it’s an experience towards somewhere along the line many years—although it could be tomorrow—when something more threatening comes to roost. I hope it will be easier to deal with as a result of having a little scary moment a few years ago. I think this is a universal thing we all get adjusted to as we get older. We have to start going to more funerals. It’s just the way things work, isn’t it? You start having more relatives and friends who are passing away. You become more acquainted with the idea of death and how to deal with it and the people you’ve been close to. It’s part of preparing for your own demise. It’s in considering these things that I guess we get more prepared for getting older.

How do those thoughts manifest themselves in your artistic process?

I find them something I should touch on in song. I wouldn’t have done it much 20 years ago, but I do it increasingly now. So, you’ll probably find a couple of songs on The Secret Language of Birds that talk about mortality and imminent death. In "The Jasmine Corridor," I’m really talking about my own demise. In "Sanctuary," I’m talking about the demise of other people or animals. I would hate for people to think this is a maudlin, depressed look at something that someone running out of steam does—reflecting on death. I don’t think that’s the case at all. I think it’s part of life to start to consider and deal with these ideas.

As a musical artist—if I can call myself that—I feel I should make these ideas occasionally part of my work and deal with that area a little bit. It’s important to come to terms with it and give it some musical and artistic validity as a thought or statement. I feel this is a part of growing up. I’m not sure if other people do the same thing as well. I’d like to think they have the maturity and capacity to introduce those elements into their work as they get older. It’s increasingly part of what we have to deal with. Rather than brood about it, or cover it up or sweep it under the carpet, it might help some people if folks like us can be seen airing these thoughts and coming to terms with them in some way. It may help other people come to terms with their own misgivings or the loss of people near and dear to them. I think it’s potentially a way of bringing changing personal realities into the process of making music, movies, writing books, painting or whatever it is you do.

You’re an avid painter. Recently, you created the artwork for J-Tull.com and The Secret Language of Birds.

Like a lot of people who do what I do that started off in the ‘60s and ‘70s, I began in art college. I didn’t go to music school. I began studying painting and drawing, then made the switch to music with about a thousand other people who are household names in British music. It seems to be a peculiarly British tradition that most of us musicians seem to have gone to art college. In America, believe it or not, a lot of musicians have actually been to music college. It’s unheard of in the U.K. in the pop and rock genre.

What connection did you feel between the visual and musical that allowed you to make the leap?

I think because of the arts education offered in the British school system, most people who want to do drawing and painting are really having to make a decision pretty early on to devote themselves to that. It’s almost like trying to become a monk. [laughs] You really cut off everything else and go to this very dedicated study of painting and drawing. I don’t know what it’s like now, but when I was doing it, a certain amount was quite formal. You learned basic stuff in terms of life drawing and the history of art. You learned form, tone, line and color. Those words are used to describe the visual arts. Coincidentally, those words are used to describe the musical arts too. So, form, tone, line and color for me were instantly transmutable into musical experiences. So, I switched to playing music when I was 19 as a more immediate way of realizing my painterly ambitions. I think I carried that through and do today by working in music from visual reference. Most of my songs and instrumental music come from a picture—something in my head, something I’ve seen, something I’ve recorded with the camera in my brain. I have a picture for every song. Quite often, when onstage, I have a picture in my head when I’m singing my songs. I really have very defined sorts of images and visual references that lie behind all the songs that I write.

Between The Secret Language of Birds, your salmon farming business and the work you do for endangered species, it seems you feel a particular connection to the animal kingdom.

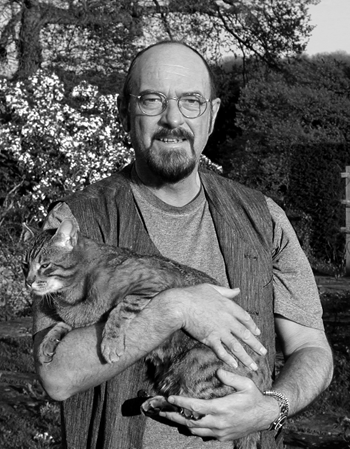

It probably goes back to when I was very small. The first animal I was fascinated by was the cat because of their independence and grace. Aesthetically, they appealed because of the way they move, the way they look and the way they torch you with their eyes. They’re unique among all the animals we know because they’re the only one that shares our home, bed, food and lives in a very intimate way. Yet it also walks outside of our house, free as the birds it chases on its own terms. It ventures out across the highway, into neighbors’ gardens, fights with other cats and comes back to us. We don’t really let our dogs or other animals do that much. Your goldfish has to stay in the bowl. [laughs] We have this unique relationship with cats. In world terms, it’s quite extraordinary when you start to analyze where this comes from and realize that we’re only talking about a generation to regress back into a feral state. It’s a very precarious relationship we enjoy with the so-called domesticated cat. It’s really only a matter of three or four generations to take a small wildcat and hybridize it into a state of total domesticity. I think with dogs it’s 12 generations from pure wild dog to a wolf to a domesticated animal. Some say less. Cats are so close to the wild and yet they’re part of our domesticated environment. That’s what makes them so fascinating to me.

I’m particularly fascinated by the small wildcats of which there are arguably 26 species on this planet—many of which are endangered seriously because of ongoing killing. They’re either seen as pests, trapped for their furs in a couple of cultures, or trapped and eaten as human food in others. They don’t get very much publicity because they’re not as big, scary and exciting as Bengal tigers, snow leopards, lions or cheetahs. They’re not big, scary animals. We’re talking about little guys here—the size of your own domestic cat. So, they don’t rank highly in the zoo fraternity—they’re not zoo exhibits. They’re economically not very viable, and I don’t just mean as zoo exhibits. It’s because we’ve globalized and industrialized our wildlife so that conservation projects tend to be those that are sexy and exciting. It’s not sexy and exciting to save some non-descript poor creature that no-one has ever seen anyway, like the Andean Mountain Cat. And there are probably so few of those left now that chances are pretty slim that they’re going to survive another 50 years. They’ve only been photographed once live and that was only two years ago.

These things concern me because once these animals are gone, they’re gone forever. They’re not very exciting to most people because they’ve not been brought to the attention of most people. So, I like to mention the fact that if you’re the kind of person that has a pet cat, it’s worth thinking that your pet cat is just a few generations away from the wildest of the wild small cats that we still have somewhere in the world. If the number of domestic cat owners worldwide would put 10 bucks aside for a conservation project, we could make sure some of these species are given the resources they need to ensure their survival in the longer term. But getting the message out there is not that easy. People like me doing it always face a bit of ridicule because of Sting and the rainforest kind of scenario—something somewhat open to ridicule and understandably so. You have to find the right way to draw attention to it without it sounding like some sort of rich man’s crusade. It’s just trying to find a balance. I feel there are a lot of people out there that would like to help and simply don’t know the scale of the problem or how to go about helping. I shall be writing an introductory piece on the small wildcats for the website at J-tull.com. I’ll be including two or three of the conservation bodies that people may want to look into to learn about some specific projects.

What’s your take on the uproar over the availability of music via the Internet?

Now that we’re entering the world of digital availability, you can bet all the record companies—particularly the major ones—are not going to let control of music on the Internet slip into the hands of a bunch of upstarts and newcomers. You can bet your bottom dollar that music on the Internet will be 80 percent controlled by EMI-Warner-AOL—or whatever it is now, BMG, Universal and Sony. Its the big guys—the multinationals. They’re not asleep on any of this. Believe me, they are going to be pulling the strings. They have the copyright on a huge, vast array of recordings and they will be making sure they retain the way to make that copyright work for them.

I understand you’ll soon be remastering the Tull back catalog for use in a number of emerging high resolution formats.

I’m talking to EMI—who own the copyright in most of Jethro Tull’s recordings—to make sure that we are working together in a positive and coordinated way to make the music available in the variety of formats it will be available on. We should be working with the original, master tapes while they’re still playable. In the last few months, 24 bit/96 kHz bandwidth archiving has become possible. So, it seems pretty important that we start now. I didn’t want to remaster the whole Jethro Tull back catalog two years ago because I saw no point doing it at 16 bit/44.1 kHz just for some crummy, old CD recording. We would have had to do it all again in the new format at much higher resolution. So, in the latter part of this year, we will start the process of remastering all of the Jethro Tull stuff and it’s probably going to take two or three years. The time and resources have to be expended in a reasoned way. It’s not something that’s been in the fore of my mind, but it should happen for technical, practical reasons. Now, it’s possible to do and it’s worth doing. DVD-Audio is going to be very exciting for everybody who likes to hear music sounding as good as analog did, but with all the benefits of digital convenience and full dynamic range of the original analog recording.

A few former Tull members have been fairly forthright about their opinions of your approach to bandleading.

As far as I’m aware, I don’t think there’s anyone who’s not talking to me. A couple of guys I would have to say we’re not buddy buddies though. We essentially don’t really get on that well, but we still talk. They’re still on the phone a couple of times a year—particularly when the royalty checks are coming through. [laughs] There’s no really bad blood out there. There’s some guys in the band who don’t get on with other guys in the band from past years. Most of them I see probably once a year. Two or three of them, I don’t see very often. But I would say most of the 22 members I’ve either done a major tour with or who have played on at least one record with Jethro Tull I probably see pretty much every year. Some of them I feel pretty close to. There’s not too much negative stuff coming out of anybody.

Assess your skills as a bandleader.

As a team leader, I’m probably not a great one. It’s because I’m a bit of a loner. I have to work with other people and I enjoy that. I need them because we are a team. When we get on a stage or if we’re making a record, every man is as important as the next. But the need for organization, direction and focus in any group of people tends to come from one person more than another. I suppose that’s the role I will try to adopt—to be a leader without being a dictator. I think the art is to lead by example and that’s the area I’m bad at. I’m not a very gregarious, fun guy who likes to hang out with the guys. I’m not very good at sitting for long periods of time drinking beer or engaging in small talk or whatever. But whenever we’re on the road and there’s a night off, we all tend to congregate and have dinner together. That’s a pretty good sign. It’s pretty much always been like that with the band. When there’s a night off, we go out together. It’s relaxing. When you’re on the stage together working, there’s an intensity, but no spoken words. You’re reading each other’s signals and nuances, but you don’t talk. So, it’s quite nice to have dinner and sit and talk. But I’m only fine at that for an hour or hour-and-a-half. I can’t make an entire evening of it because we all have different interests and backgrounds. We’re not in each other’s pockets. We enjoy each other’s company, but sort of in measured doses. We don’t have disagreements, arguments or fights. At our age now, we’re more mature than we were 20 years ago. When you’re younger, you are a little more volatile and perhaps a little less tolerant of each other’s shortcomings. You learn as you get older that when things irritate you, you take a step back and don’t let it get confrontational. So, the art is leadership and tolerance.

How have your leadership skills evolved over the years?

I’m probably getting better at it, not worse. But I wasn’t much good at it to begin with. I hear stories about people like Van Morrison, the late Frank Zappa and Carlos Santana and sometimes they really make them sound like very dictatorial and unpleasant people. I’m inclined not to believe the stories. I think the truth is probably that they might on a bad day be a little intimidating. I think for the most part, stories like that are exaggerated. That’s my opinion—my belief. So, I would guess they’re a little like me. They’re people that most of the time are pretty good guys to work with, but once in a while we get a little cranky and need a little space to ourselves. But that’s because of the great burden we have to shoulder. [laughs] Some of the other guys in the band just have to show up for work and remember where the catering room is. Some of us have to worry about things like doing all the promo. My weekend will be spent with the aid of my computer programs and software researching hotels for the upcoming American tours and supplying our travel agents with the addresses and phone numbers of each hotel in each town I want to get quotes for. That’ll take me about eight hours of work to do. And in the meantime, production management will be working on the flight auctions. So, we have a pretty busy weekend coming up and that’s not something that has to worry the bass player, God bless him. [laughs]