No-Man

Positive Momentum

by Anil Prasad

Copyright © 2008 Anil Prasad.

Throughout 21 years as No-Man, Tim Bowness and Steven Wilson have gone from strength to strength across their six albums together. No-Man's back catalog reflects a duo with a voracious appetite for myriad genres and a fearless approach to incorporating them into its moody and mercurial songs any way it sees fit. With the exception of some record company meddling in its earliest incarnation, No-Man has taken a zero-compromise approach to its work. It’s why its fiercely devoted audience has evolved gradually over its career with word-of-mouth mostly eclipsing conventional media-driven awareness. Indeed, it’s hard to find a No-Man enthusiast that doesn’t act as a champion for its output.

The pair’s latest CD Schoolyard Ghosts will surely further that inclination. It’s their first release in five years and unquestionably the most ambitious and absorbing one to date. The disc is full of sweeping, cinematic contrasts designed to evoke a broad emotional spectrum. And while it features the most life-affirming lyrical content in No-Man history, it’s unafraid to reveal the journey through darkness that led to more hopeful realms. “Truenorth,” the album’s centerpiece, is a shimmering, semi-orchestral epic that specifically traverses that thematic territory. The album is further characterized by several exquisitely delicate and spectral songs including “All Sweet Things” and “Wherever There Is Light.” A stark contrast is found in the volatile “Pigeon Drummer,” a distortion-laced track that’s likely the most aggressive venture the duo has engaged in together.

Schoolyard Ghost’s cast of supporting musicians is comprised of close friends and acquaintances sympathetic to No-Man’s diverse leanings. Drummers Gavin Harrison and Pat Mastelotto, bassist Colin Edwin, flautist and saxophonist Theo Travis, arranger Dave Stewart, and the London Session Orchestra all lend their talents to the effort.

While Bowness and Wilson remain committed to No-Man, the fact that both are involved in a wide variety of outside projects has helped keep the partnership fresh and relevant. In the intervening years since the last No-Man CD, 2003’s Together We’re Stranger, Bowness released 2004’s My Hotel Year, a critically acclaimed solo disc, and worked with the likes of Centrozoon, Rajna, Henry Fool, Nosound and The Opium Cartel. During this period, Wilson released two commercially successful records with Porcupine Tree, including 2007’s Fear of a Blank Planet, an album that’s positioned the band on the brink of major, mainstream success. He’s also been responsible for many other discs including ambient explorations with Bass Communion and Continuum, and infectious, more accessible rock explorations with Israeli pop superstar Aviv Geffen in Blackfield.

Bowness and Wilson spoke to Innerviews individually about the making of Schoolyard Ghosts and No-Man’s 2008 European mini-tour—its first live shows in 15 years. They also discuss their forthcoming solo projects, as well as perspectives about keeping physical music releases alive and thriving in a marketplace increasingly dominated by downloads.

Steven Wilson

No-Man represented the beginnings of your life as a professional musician. In recent years, you’ve taken on myriad other projects. What was it like to revisit No-Man within the context of everything else you have going on?

It was quite interesting. I felt we had made definitive No-Man records with Returning Jesus and Together We’re Stranger. I wasn’t sure what direction a new No-Man project would go in. Also, my other commitments meant there were scheduling concerns. Initially, I said to Tim “Why don’t you go write the record with other people and bring it to me. I’ll help you make it, produce it and give it the No-Man sound and mix, and ensure it sounds really nice.” Of course, that’s not what happened at all. What transpired was that as soon as I had the opportunity to meet with Tim and listen to some of the songs, I got excited about No-Man again and quickly and completely got back into the swing of it. I really enjoyed working with Tim again. It felt so inspirational in terms of becoming another truly collaborative No-Man album. I think it’s our best yet. I was pleasantly surprised that we could so easily create something that sounds so fresh and yet so specifically No-Man at the same time.

The new album came together over a few sessions in a matter of weeks. Describe the creative process that enabled you to bang it out so rapidly.

Yeah, it definitely came together really quickly. Although the idea was originally for me to produce and arrange songs that Tim brought in, once I listened to the material, I’d say “Good song there, but I think it would be nicer if it used different chord changes.” I began to go into the music and before I knew it, I had actually thrown away almost everything musical that had been there before and constructed my own music around the vocal lines. The best example of that is the track “All Sweet Things” in which the vocal melody is from a different song Tim had written with Peter Chilvers. I literally wrote all new music and chord changes underneath the vocal. This approach wasn’t planned, but I guess I’m just such a control freak at the end of the day that I always think I know best. [laughs] As soon as I started to pick apart the music, I found that I was sometimes virtually creating something completely new. That happened on a few tracks. There’s another one called “Truenorth” in which the first part comes from a piece of Tim’s. It was a two-and-a-half minute miniature which basically makes up the first two minutes of the song. When I loaded it up onto the computer, it immediately suggested other things flowing out of it. In some circumstances, it was a case of replacing the music that was there. In others, it was a question of using the music or a fragment of the music as a starting point for something longer. In the case of “Truenorth,” it ended up being 13 minutes long, when the genesis of the piece was the first two minutes of it.

Since No-Man began, you’ve emerged as an accomplished songwriter in your own right. Did you consider collaborating with Tim on lyrics for the record?

Not really. The No-Man partnership has existed for so long. I was writing with Tim before I ever thought about being a singer, writing my own words or having my own projects. My relationship with Tim goes back longer than Porcupine Tree. Singing and lyrics were always Tim’s thing. That’s what he does. So, it didn’t feel odd to keep that division of labor, even though there’s been a five-year period in between No-Man projects in which I’ve done things where I’ve been the singer and lyric writer. In fact, it was remarkable to work with Tim again. Literally, within a half-hour of working together again, we clicked back into No-Man mode just like we did 20 years ago.

We do have this rather strange working relationship which is very different to any other one we have outside of No-Man. We’re brutally honest with each other. Tim is one of the few people I can be that way with. I can listen to a demo he brings me and say “That’s fucking shit Tim,” and he won’t get upset. He can do the same to me. Neither of us have ever worked with other musicians that are so desensitized to that kind of criticism. [laughs] I think I’ll only take it from him and he’ll probably only take it from me. We’ll go to the studio and I’ll say something like “Hey Tim, why don’t we load up that fucking piece of shit you brought me yesterday and try to make something decent out of it? God knows it needs help.” [laughs] I’m not saying it’s always like that. It’s not. But because it’s a very long and fruitful relationship, we have the ability to be that frank and honest about things.

I understand quite a bit of material fell by the wayside during the making of the record, including what Tim referred to as a “20-minute disco epic.”

Originally, I had this idea that the next No-Man record should be a step into something different. I revised my opinion and went more along with Tim’s plan, which was it should be a refinement of something we have been gradually engaging over the last two records, which is this sort of epic, romantic and very textural direction. Because of the quality of the music we had made in that style, I found it very difficult to argue with that perspective. The music we’ve made in that style sounded so good and hung together so well. Therefore the disco epic felt like it was a choice for another day. The material that felt strongest in the end was that which was the most typically No-Man-esque. It’s not like we’re churning out three albums every year in that style. It’s been five years since the last one, so it’s appropriate. I do feel the new album is a definite step up in terms of quality and craftsmanship.

The album has a brighter, more optimistic feel compared to previous No-Man efforts.

That’s true. The bent of some of Tim’s lyrics, in conjunction with the musical accompaniment, is significantly different than past No-Man records. Sonically, your observation is accurate as well. Contrasted against previous No-Man albums and Porcupine Tree output, that’s a pretty significant shift. One other thing I was aware of when doing the record, and this is possibly inspired by the demos Tim brought in, is that there was almost a nursery rhyme simplicity to the songs. The exception is the last track “Mixtaped,” which is an incredibly lugubrious piece of music. By nursery rhyme, I mean that my choice of sounds turned to glockenspiels, celestas and musical boxes. There was a kind of Danny Elfman influence on certain tracks with a cinematic quality going on. I suppose that’s different from what we did on Together We’re Stranger, which was an almost epic, portentous record. The new record has moments of child-like simplicity. It also has moments of optimism and joy, with the exception of the final track. But yes, I can see that. This change was something unplanned. We didn’t sit down and decide to do this, but in the five years since we made the last record, we’ve both changed in large and small ways, and that’s reflected on Schoolyard Ghosts.

How has Tim has evolved as a vocalist in the years since the last No-Man project?

If you follow the trajectory of his catalog and how he sings these days, it’s very interesting to witness how his vocal style has become more natural. He definitely has an incredibly distinctive and instantly recognizable style. Today, it’s much more relaxed than it used to be. In the early years, Tim’s voice was almost melodramatic and I know he feels that way too. What he’s arrived at is a very warm and resonant sound. Also, I was pushing him to try and stretch out a little bit and try some different things on this album. For instance, on “Pigeon Drummer,” I said “Try to sing it like you really don’t give a shit.” [laughs] Tim remains a pleasure to work with because he’s still so passionate about making music. We both are. I think when we get together, there’s something unique that definitely happens.

You and Tim have long talked about using real strings on a No-Man record. You finally got your chance on “Truenorth.”

We used the same string team as on the recent Porcupine Tree records. Within the No-Man context, one of the things Tim and I bonded on early on was our love of melancholic, romantic, string-oriented ballads. I’m thinking of early Nick Drake, Sandy Denny and Scott Walker records. In a sense, strings were always a big part of No-Man, right from its first line-up in which we had a violin player. We were always using sweeping orchestral samples and synth sounds as well. However, we could never afford to use a real orchestra. It’s very expensive. It’s a major investment. In fact, 95 percent of the budget of this record went to the string session. I think it was worth it because you finally get to hear real sweeping strings on a No-Man track. There’s no substitute for them. We’re both really happy about it. I’m being slightly disingenuous when I say 95 percent of the budget went to the strings. The rest of the album cost virtually nothing to make. We had a couple of guests, but apart from that, it was all done at home. What I’m saying is the budget we did use was spent on the string session and I was very happy to do that.

Tell me about the process of directing orchestral musicians within rock and pop contexts.

In this case, it’s a question of providing the basic demo to an arranger, who in this case was Dave Stewart. Tim and I did our very remedial one-finger string lines using samples and gave those to Dave, along with the MIDI file. He then makes it sound proper and brings a different sensibility to it. He also offers ideas of his own. So, in terms of process, you have to find a good arranger you trust and have faith in to translate your thoughts. Dave did the last Porcupine Tree record Fear of a Blank Planet and did a fantastic job on that. It was as simple as calling him and saying “Dave, make our record sound good and our string arrangements sound proper,” and he did.

Take me behind the scenes of constructing “Pigeon Drummer.” It’s probably the most mercurial track you’ve done since Wild Opera.

Tim brought in a demo of a song called “Outside the Mercury Lounge” on which he used a loop from GarageBand. He had also written this mellotron thing over the top. At first, we started developing that. Coming out of that, I wrote the other non-rhythmic parts of the song, but the balance shifted at some point from being very rhythm-oriented with a short interlude to the other way around. The rhythmic parts became the interludes that broke up the other parts of the song.

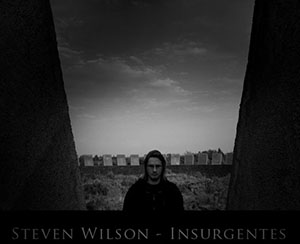

The other thing that manifested itself is my interest in extreme noise music. It’s something you’re going to hear a lot more of on my forthcoming solo album Insurgentes. I’m a big fan of pure noise, like Merzbow’s stuff. There are definitely elements of that on “Pigeon Drummer.” The contrasts are extreme on that track. It’s akin to the last Scott Walker album The Drift. Having incredible noise followed by incredible beauty or ambiance is something I really love. And you’re right, it’s the only moment on the record when you get a sense of what we were doing a few years ago on Wild Opera. Pat Mastelotto did a great job on the rhythms as well on that track, although everything is going through a distortion box on the noisy sections, including the drums, keyboards, guitars, bass, and voice. It’s pure white noise. I love it.

No-Man is about to play its first concerts in 15 years. What made you want to explore that realm with Tim again after such a long absence?

I previously told Tim “I feel like my schedule is holding you back. No-Man should tour.” It’s one of the things that’s been a problem over the years. I thought on the back of the strength of this record that it should happen. Tim already has a band that he’s been using for his solo shows. They’ve been playing No-Man songs too. I said to Tim “Why don’t you use that band to rehearse a No-Man set and I’ll come along for a couple of days and fit myself in around the songs?” However, I know from experience, and from having done this record, that it’s not going to happen like that. What’s going to happen is I think that’s how it will go, then I’ll come along to rehearsal, and because I’m such a ridiculous control freak, I’ll become much more involved than I planned to. That’s okay. It’s the way that I am. Basically, this whole album involves Tim driving things, because my list of things to do is much too long. I need other people to push me to prioritize things by getting the ball rolling. Tim realizes that’s what he has to do with No-Man. Once the live band is going, I’ll come along and throw myself in as passionately as I ever have. So, that’s the plan.

Beyond the tour, what’s next for No-Man?

I’m very much into the whole of idea making further albums with No-Man, and we’ve already started talking about ideas for the next one. Part of the problem with getting this one off the ground is so much has happened to me between No-Man projects, particularly with Porcupine Tree. Now, I realize that it’s as easy as it ever was. This album came together so easily and naturally, and is our best record to date. So, my thought is to keep No-Man going as long as we can make good music together.

What can you tell me about Insurgentes, your upcoming solo album?

It’s different from anything I’ve ever done before, otherwise I wouldn’t have bothered. It’s song-based, but it’s the most experimental song-based music I’ve made. Everyone assumes that when I’m doing a solo album it’s going to be metal-oriented, but it isn’t. There’s no metal in it at all. I know I’ve spoken about making a metal album in the past, but it’s anything but that. It has everything from noise to drone stuff on it. It has a song I recorded live in a church in Mexico with just piano and voice that’s very simple. There are influences from post-punk shoe gazer music like Joy Division and The Cure. There are weird time signatures and orchestras playing bizarre, atonal, almost horror soundtrack stuff. It’s a real eclectic mess and it’s probably the kind of thing only I could ever like all the way through. [laughs] But you know what? If I’m going to do a solo album, I’m going to do it for myself. I should make the kind of record I myself would like to listen to, and I have. It sounds clichéd to say that, but it really is true. This album is going to sum up all of these different aspects of my musical personality.

To say you’re prolific is a dramatic understatement. How do you keep creativity flowing across so many simultaneous projects?

The answer is really easy. It’s just that I love music. A lot of musicians that have got to the stage I’m at in my career after 20 years don’t actually like music very much anymore. I still do and I remain incredibly passionate about discovering new music. I’m always searching for the most obscure music on the periphery. I’m not interested in mainstream music. Someone asked me the other day if I had listened to Snow Patrol. They’re one of the biggest bands in England with huge hits. They play stadiums. I had never heard of them and I have no interest in hearing them. It’s astonishing because you really can’t avoid them. They’re in every store and on TV every 10 minutes. I’m proud to say I haven’t though. I’ve immersed myself in music that’s outside the mainstream and I don’t really care for what’s going on within it.

I find there’s so much fascinating music happening in the underground—more so than ever before. The availability of home recording technology and the fact that you can market music through the Internet fairly successfully has played a role in this. You don’t even have to sell hundreds of copies. There are great artists out there just making 50 CD-Rs of each release and they have a loyal, small audience. I have music by artists that sell that many and I love it. I have a real passion for discovering them and it’s that underground music which informs most of my own work.

As I mentioned, I have a huge interest in noise music. It has a very, very small audience. Even if you say Merzbow is the superstar of noise music, most of his records do well to sell 1,000 copies. I’ve found great inspiration from Merzbow and industrial movement artists from the late ‘70s and early ‘80s. The same holds true for drone music, another very small niche form which I love. The interesting thing is when I make that kind of music with Bass Communion or Continuum, it starts to have an impact on my other projects, including No-Man and Porcupine Tree. In that sense, those forms of underground music become research and development for what you might call my more accessible projects. I think that’s the key to why they remain fresh and continue to evolve. Another example is my interest in death metal, which of course had a massive impact on Porcupine Tree. It’s not that Porcupine Tree became a death metal band—far from it—but it’s very easy to hear how that music has kept Porcupine Tree fresh and allowed it to continue to evolve.

Speaking of the mainstream, I heard you were once asked to produce a huge pop band at one point. Who was it?

It was a boy band that was very successful. They were contemporaries of Boyzone. I can’t even remember what they were called, but they were huge for a week. Their manager happened to be a big fan of Porcupine Tree and asked me to produce them. And you know what? I actually went to the meeting because it was so bizarre. I was fascinated by the idea. I thought “I have to at least go to the meeting to meet these kids and this guy.” I knew I wasn’t going to do it, but it was such a bizarre thing to be asked to do. I guess it happens all the time. You hear stories like Madonna asking Richard James to produce her. I even heard a story that Lewis Taylor was asked to write an album with Joss Stone and that he was going to be paid $500,000, but the condition was he had to pretend she had written it. This is quite a depressing thing to consider. I guess shit like that goes on all the time, you know? These kinds of big, mainstream artists can just buy themselves songs and claim that they wrote them.

Blackfield made great strides in 2007. What’s coming up for the duo?

I think we’re going to tentatively start working on some new songs and that’s as far as we’ve got regarding planning. I think there almost certainly will be another record. As with No-Man and my other projects, there’s no reason to stop doing them as long as the music keeps flowing.

I met you and Aviv Geffen backstage in San Francisco in a dingy dressing room of a small club. I thought it must have been surreal for Aviv to be hanging out in such a dank environment considering his status in Israel.

He loves it. It’s like a busman’s holiday for him. I remember having the same feeling about Richard Barbieri when he joined Porcupine Tree in the ‘90s. I thought to myself “There’s no way Richard is going to put up with playing these horrible little clubs he feels he must have left behind years and years ago after playing the Budokan and Hammersmith Apollo.” To be fair, the feeling wasn’t so dissimilar for me when playing with Blackfield. I felt I had left those venues behind as well, but it’s amazing how easy it is to adapt to going back to that. Aviv does love it though. One of his dreams as a kid growing up was to be in a bus touring the world. Being a mega-star in Israel, he never really goes on tour as such. If you’re based in Tel Aviv, the furthest you go is like Haifa, two hours up the road. So, the whole experience of being on tour, being on a tour bus with the band and crew holds some romance for him. He loved it more than I did, I can tell you that. Being in the grotty dressing room was like some romantic idea coming to life for him, bless him! [laughs] I was probably feeling more of a comedown than he was, but we had a great time on that tour. It was good fun.

You’re amazingly adept at creating and selling CDs and vinyl in beautiful, extravagant packaging. However, it’s clear the momentum is now on the side of downloadable music. How are you coping with this trend?

I’ve put a lot of thought into ways to persuade people that buying a CD is something they should still consider. When you buy a CD, you’re buying a piece of art. For me, it’s the difference between a JPEG on your computer or having a real painting hanging on your wall. I don’t think I’m the only one who thinks this way. If you look at the record stores these days, you’ll see an increasing amount of special packaging, limited editions, CDs with DVDs, CDs with special digipak sleeves and foldouts, and boxed sets. I believe this is a way of offering fans who would otherwise download music a reason to buy physical product.

It’s interesting that my physical record sales continue to go up. I know I’m not the only one who’s experiencing that. Michael Akerfeldt from Opeth told me that their record sales are rising as well. It’s interesting that the bands more closely associated with metal and heavy rock are finding that their record sales continue to go up when the rest of the industry has basically died. If you think about it, these are bands that have a young fan base that not only wants to buy the record, but buy into the whole world of the band as well. That means buying the t-shirts, posters and the actual physical music product. For young kids into metal, it’s still a badge of honor to have a collection and really own this stuff.

I’ve always been into special packaging. It’s not new to me, but I think it’s one of the reasons why Porcupine Tree and No-Man continue to buck the trends in terms of being on an upward trajectory when the rest of the industry is going the other way. It’s because the kinds of fans we have and the kind of packaging we encourage is a good combination for people who feel like they want to own something. I think things are more of a problem when it comes to the pop and R&B side of the market. I mean, who really wants to own a Britney Spears or 50 Cent CD? You’ve seen the packaging. It’s some cheesy shot of the artist on the front cover of a four-page booklet stuffed into a crystal case. I’m not surprised no-one wants to buy those CDs because it just feels like you’re buying a piece of software. And if you’re just buying a piece of software, why not just download it as a piece of software?

I think the future is represented by what Radiohead and Nine Inch Nails are doing with their packaging. They offer people the opportunity to buy their physical product, but also to download music onto their iPod too. But personally, I’m terrible about downloading. I’m not interested at all. I won’t even listen to downloads. If someone sends me something to download, I won’t do it. If you send me a CD, I’ll listen to it. I don’t know what it is, but I love the idea of owning or collecting. I think you can still nurture that and encourage people to buy into the universe of a band or artist. Again, it’s interesting that this is happening almost entirely in the rock field at the moment. It’s not happening at all in the pop, R&B or hip-hop ends of the market, which of course is where most of the record companies have put their loyalty in the past 10 years. But if you talk to labels like Snapper, Peacefield or Roadrunner, these companies are selling more records than ever before. If you talk to Atlantic, Universal or EMI, they’re in big shit because of the kinds of music they’ve chosen to market. That’s my perspective on things.

Having said that you’re disinterested in downloads, you have started selling downloadable-only material as well.

Yeah, we have. The reason for that is, at the same time as I’m saying I’m dissatisfied with downloads, I am very aware of the fact that there are many people out there that would like our music that way. These people won’t buy the physical product no matter what we do. So, we started making our music available as downloads. We’ve also found that downloadable formats are very useful for things that have been previously issued as physical product as limited editions. You don’t necessarily want to reissue them, but a good compromise is to make them available digitally. In fact, we did that with the Returning Jesus demos, which were only previously available on vinyl. We put them out as very high quality downloads for those uninterested in vinyl. I think that’s a good positive use for downloadable material.

Of course, my worst nightmare, as you can imagine, is a world without physical product. For me, the romance of making records is what I fell in love with. I fell in love with the idea of holding a record in my hand and saying “I made this.” How can anyone fall in love with the idea of making a downloadable MP3? That’s so anathema to what I consider the attraction to becoming a musician and making records, but there is definitely a place for downloads.

Tim Bowness

What was it like for you to revisit No-Man after a five-year break?

It was interesting in that the first session was almost a case of learning to work together again. The break was useful because we’ve worked with a lot of other people and gained new experiences and influences. As with a lot of No-Man albums, I think it benefited from the changes in our lives, which also influences the way we approach our music. By the second and third sessions, I think the personal and musical chemistry reestablished itself. By the end of the sessions, it felt as good a project as No-Man has ever done. After 21 years, we’re still enthusiastically making music and feel the band still has something new to say.

Steven said he wasn’t sure if the last two No-Man records could be topped. What’s your perspective?

We did reach a peak with those records. In some ways, Together We’re Stranger was a really interesting album in that it happened very quickly off the energy and response we got from Returning Jesus. We took five years to do Returning Jesus and it was an incredibly important timeframe in that we waited for the right musicians and material. There were a lot of casualties on that album in terms of tracks that were dropped, as well as arrangements that were dismissed. It became a very precious album to us and took an awfully long time to realize it in the way we envisaged. Together We’re Stranger was the opposite in that it happened quite spontaneously and was completed very quickly. It also features fewer guest performances than any other No-Man album. What we created between the two of us just seemed so complete. When we got other musicians to work on it, it was as if they were ruining the vision or adding too much color and intricacy. We thought they were taking away from the actual sentiment behind the music, despite turning in fine performances.

Those albums were interesting contrasts and represented the best of what we’d done to that point. Certainly, I’d say Schoolyard Ghosts is even more so the case. It represents a band that has found its voice, to the point where it’s writing without particular regard to influence or any specific plan. It’s pure music created by two people working on an emotional basis. I agree with Steven in a sense. I was genuinely worried we couldn’t top the intensity of Together We’re Stranger, but I felt it was worth the attempt because the personal and musical experiences we had in the interim would contribute to us having something different to say. Luckily, that was the case.

How do you feel Steven has evolved as a musician in the five years between No-Man releases?

Steven continues to improve as a musician and technician. He’s always a joy to work with in the studio. He does superb work very quickly. There’s a certain effortlessness to what he does. I think you have to be extraordinarily good to achieve the level of effortlessness Steven has attained. Steven’s core talent was always facilitating. The artists he’s been working with in the interim have further enhanced those skills. He’s more accomplished than ever in this regard.

What evolution do you feel you’ve experienced in the intervening years?

I’ve always seen music as a means to further a continual journey towards finding myself. It felt to me on this album that I'd achieved an even more natural performance. It felt as if I’d gravitated towards something different. It only became clear when listening to back to Returning Jesus and Together We’re Stranger, while making the new album. As much as I love the work I do, it would be extraordinarily vain to mostly listen to my own stuff, so I tend not to do this until I’m working on projects. Before making Schoolyard Ghosts, I went back to listen to early No-Man material, and what really surprised me, especially with the singing on Returning Jesus, is that it seemed slightly more heavy-handed and affected. There were ways of singing that I would never think of using now. I wasn’t actually aware of it until I listened back.

Over the last few years since I did my solo album My Hotel Year, I’ve continued to write and be very productive. I’ve also become extremely self-critical. I feel most of what I’ve done hasn’t been as good as No-Man or My Hotel Year. The music may be interesting and listenable, but I strongly believe you should only release what you would fall in love with yourself—something you would actually buy and be excited about as a listener. I can’t really say that in the last four years that a lot of what I’ve done has excited me in that way. But as soon as we started working on Schoolyard Ghosts and these pieces started evolving, I began falling in love with them as a listener. I feel we’ve made an album that is quintessentially No-Man. It really captures the essence of the band while having a different emotional and musical value. Schoolyard Ghosts is the antithesis of Together We’re Stranger in many compositional ways. There really is a greater level of confidence on the album.

Describe how Schoolyard Ghosts is the antithesis of Together We’re Stranger.

Together We’re Stranger represented a drift towards improvisation whereas every aspect of Schoolyard Ghosts is much more tightly composed. If you take a track like “Truenorth,” you’ll hear that most of the musical moments have a purpose. The one thing that’s really interested me in the last few years is avoiding the trap of creating tracks, rather than songs. The distinction with tracks is that you may have interesting two- or four-chord grooves that you develop in distinctive ways but never take any further. That’s a totally valid means of experimenting and something I continually do, but I felt very strongly that on some levels the craft of songwriting has been neglected by lots of very good musicians who use this method of music making. Basically, many people take a three- or four-chord trick, a verse and a hook and assume that they have a complete song. As I said, that’s valid, but I think on Schoolyard Ghosts, there isn’t a wasted note or arrangement. We returned to the compositional complexity of tracks like “Angel Gets Caught In The Beauty Trap” and “Days In The Trees”—pieces that are very much crafted songs.

How did the creative process change between the last album and new one to encourage this shift?

Knowing we’re working on a No-Man album, Steven will typically have about five or fix demos he submits to me, and I’ll have two or three demos that I submit to him. Then we write in the studio and together create a pool of 12 or 13 pieces that we can then choose the best work from. This time, it was very much a case of me mostly submitting demos. Perhaps 90 percent of the origins of the music on Schoolyard Ghosts come from demos I submitted, but Steven definitely gave them a greater depth and compositional complexity than I ever would. I should also mention that with this album, I think Steven got bored of drift and atmosphere. It’s something he can do to his heart’s content with Bass Communion, so he was keen to compositionally challenge himself and take material into unexpected harmonic territory.

Why did most of the initial writing responsibility for Schoolyard Ghosts sit atop your shoulders?

The continuing success of Porcupine Tree and the emerging success of Blackfield meant that Steven had far less time for No-Man than he’s had in the past. However, the fact that I brought in the majority of the ideas doesn’t detract from the fact that he brought as much musicality to this album as to any other No-Man project. “Truenorth,” which is my favorite No-Man track of all time, is a great example of how the process works. The first few minutes result from a demo I submitted. It even contains the guitar and piano work from my demo. Steven then took this into two other sections which really effortlessly and seamlessly evolve out of the original sequence and ultimately provided us with something that was new for the band. This album contains some of Steven’s most sophisticated and interesting writing. Certainly, “Truenorth” is a great example of that. In particular, the third section’s transitional moment is one of his strongest lines.

The whole beauty of No-Man is that I think we both bring something to one another. I’ve always felt there’s almost a Gilmour-Waters or Lennon-McCartney thing happening with us. I think the balance in our relationship is that he musically sweetens what I do and takes it to the place I’d like it to be. And I think I provide a certain intensity to his music that is different from any intensity in other music he does. A lot of the emotional qualities of No-Man stem from my involvement, and interestingly enough, I probably had more of a musical say and contributed more music to Schoolyard Ghosts than I even did to My Hotel Year. I feel that Steven’s production and musical expansion of what I’ve given him has taken this way beyond the solo album I had absolute control over. I don’t like My Hotel Year nearly as much as any No-Man album. I think it’s good, but has a relentless bleakness that I could do nothing about at the time. Perhaps left to my own devices, my mind goes in that direction.

Schoolyard Ghosts has a more spirited outlook compared to most of your previous output. Tell me about that change.

I’m not sure why it emerged that way. I do feel this is a more optimistic work. I have to use a terrible cliché by saying it represents the light at the end of a very dark tunnel. I hope the lyrics don’t flinch in describing that darkness. I wouldn’t want to explain it specifically because this album emerged as the outcome of some negative personal circumstances. As I said, it is easy to fall into the trap of producing relentlessly bleak music. In the back of my mind, I felt I had gone too far in that direction and that I should rethink things. Oddly enough, it was more of a challenge to create something with a more positive outlook, particularly as the result of going through some extraordinarily bleak circumstances.

Most people reading this have dealt with terrible circumstances, including death and the breakup of important relationships. These make us question our very existence, but ultimately, the ameliorating power of our love of life helps us find meaning, despite the darkness. That was one of the overriding themes behind Schoolyard Ghosts. No matter how bad my life has got, I've known that on a personal level I'm capable of recovery and feeling renewed. It’s something we all have the capacity for. We can all regain our equilibrium and positive momentum in life despite the sometimes bleak reality of our circumstances. I lived through many dark periods growing up. When I was 17 or 18, I went through a very self-reflective, introspective period. That’s when my passion for music emerged. I was amazed that at the end of such a difficult time, I could feel positive again.

How did you and Steven mitigate the possibility of repeating yourself with Schoolyard Ghosts?

We didn’t talk about that other than having discussions about concern over topping the previous two albums. The music I wrote for the album came about with no conceptual pre-planning. I took the 12 pieces from my original sessions—eight of which I wrote myself and four which were co-written—and gave them to Steven. He said which tracks he liked and didn’t like and started developing the ones he liked further. This album had a three-tier process in which I would submit something, then Steven would select what he liked instinctively, and then the two us would begin the production process of enhancing the songs. In terms of repetition, there are certain lyrical themes that I revisit, and this is not intentional, but what one eventually writes is usually linked to their instinctive outpourings lyrically and musically. I wasn’t all that conscious about how the music was linked to the lyrics until the very end. That’s when I realized Schoolyard Ghosts was something quite different from its predecessors. Steven feels the same way.

Steven mentioned that he feels you and he can be unusually brutally honest with one another—something neither of you experience in other contexts.

I agree. Although No-Man produces fragile, emotional music, the process is far from fragile and beautiful. [laughs] We can be incredibly brutal, sarcastic and comical with one another. The creative process is often more fun and aggressive than most people would imagine. What Steven says is true. Quite often when I do sessions for people, they want that “Bowness sound” on their album. So, I’ll sing and get no feedback. That’s not to say the work is poor and they’re not being genuine, but I’ve given them what they want and it’s over. Steven has that to the power of 10. People just want to work with Steven, so they will accept what he gives them without question.

In contrast, we’ve known each other as people since we were very young. We started writing 21 years ago and knew one another before the phenomenon of Porcupine Tree and No-Man getting signed. The legacy of our early freewheeling relationship has remained. When we first started working together, the sessions were funny, brutal and honest. They still tend to be that way. He definitely says things to me no other musician would, and vice-versa. The good thing about that is he’ll get me to rethink a vocal line and certain clichés that I automatically revert to. He’ll make me think about what I’m doing more than anyone else I work with. Similarly, he can do things that I just dismiss in a comic sentence. I doubt that would happen on most of the other projects he’s involved with. I imagine most people would take whatever he gave.

You discarded quite a bit of material when making the new album. A “20-minute disco epic,” as you called it in your diaries, seemed to be the most significant casualty.

That was a piece we’ve been working on since 1994. It was originally pushed aside during the Wild Opera sessions. That was our most productive period together. This was the time we were most in the studio. Some tracks from that period emerged on Returning Jesus because they didn’t have a natural home on Wild Opera. “Lighthouse” is an example. The 20-minute disco epic is called “Love You to Bits” and was written during this period. Periodically, we’ve gone back to it, but it never seemed right for any project. On this occasion, I thought it would have been a fraud in that we had completed 30 minutes of really exciting new material, and adding this 20-minute reworked, reheated piece to fill it out after five years apart didn’t seem quite right. It didn’t have the spirit of the new material. Once Schoolyard Ghosts took on its own momentum, it became clear that we should come back to that piece at some other point, perhaps on another Lost Songs release.

The other thing is that I couldn’t enter into the mindset I was in when I wrote the lyrics for “Love You to Bits” and a few of the melodic sections for it. Steven developed the track even further and liked it so much that he was considering putting it on his upcoming solo album. But then he had written so much for it that he dropped it. So this track has been dropped from about seven albums. It’s guaranteed to disappoint when it’s finally heard. [laughs] It’s difficult to describe in terms of the No-Man canon. It’s a really extreme extension of the experimental elements of where we were on Loveblows and Lovecries.

“Truenorth” is one of the most ambitious pieces No-Man has released. What it was like for you to work with the London Session Orchestra musicians during its creation?

It was a wonderful experience. We got Dave Stewart to do the arrangements, which was fantastic. It was extraordinary listening back to something that had its genesis on my laptop in GarageBand played beautifully by a 22-piece orchestra. The impetus for "Truenorth" came out of a song of mine called “Another Winter” and that’s where the first few minutes of the track come from. I felt that it would provide a really interesting springboard for a larger composition. Steven seamlessly created two powerful new sections for it. What struck me was how natural his musical additions seemed to be within the context of my original piece. The lyrics naturally evolved as I wrote for the second and third parts. That was also extraordinary given that it had been a year and three months between the first part of writing the song and last two parts. Yet the narrative naturally flowed and in the end it was some kind of journey from personal stasis to overcoming extreme depression. It deals with finally finding the strength to get outside of yourself and sample the real world, instead of dealing with an internal imagining of the real world. From a musical point of view, I’m extremely impressed with what Steven came up with. And the orchestra was as good as we hoped for. It was like watching a small seed growing into a bloody huge oak tree.

“Pigeon Drummer” is the album’s most kinetic track. What made you want to use such a roller-coaster arrangement for it?

That track stands lyrically and musically alone on the album. It emerged out of a demo called “Outside the Mercury Lounge.” This was one Steven really loved. We tried to develop it as a big production number from my demo and it wasn’t working. We forgot about it and then came back to it two months later because I felt there was something dynamic in its intensity. We started from scratch using sections of the original as a starting point. Essentially, the demo was ripped apart and reassembled with a very Danny Elfman-esque structure. It was incredibly enjoyable to do and we quickly realized how different it was from the rest of what we were working on. The track is reminiscent of material from Wild Opera. However, the difference between “Pigeon Drummer” and what we did on Wild Opera is that every section on the track is carefully composed. It has a more sophisticated structure than anything on Wild Opera. We used Pat Mastelotto on this track. He’s a very underrated drummer. What’s exciting is that he’s in his 50s, yet still finding new ways to do what he does, particularly using technology. He’s very enthusiastic and talented. After a few days working with him, we dubbed him “Pigeon Pat” because he did such a perfect job.

No-Man is doing a number of shows to support the new album—its first gigs in 15 years. What prompted you to finally undertake more performances?

We did an impromptu No-Man reunion performance two years ago and it was incredibly powerful. We both felt there was a way for No-Man to become a live band again as a result. We also feel we have something worth promoting, so that’s an additional motivator. We’d like this album to be more visible than previous albums. What’s going to happen with these shows is that half will be a reflection of exactly where the band is today, with real music played in real time. Half the set will be a nod to the past. It will be interesting to see how I feel about going back to those old songs and if I have any emotional connection with that material. It will be exciting to see how we reflect our past.

The first show in London in late August will be filmed for a DVD release. A guy is also doing a documentary on the band which we’ll include in the package. The DVD will probably also include footage of the rehearsals and interviews done in the days leading up to the show. After these few shows we’re doing, we’re hoping that after Porcupine Tree’s touring commitments we can do a mini-tour of Europe. We have an agent and interested venues. We barely had those when we signed to major companies in the early ‘90s. The people working with us are more excited than anyone else we’ve dealt with. They are much more committed to the artistry and idealism of what we do.

The No-Man live band is your solo band plus Steven. Tell me about the personnel involved.

Michael Bearpark, one of the most underrated musicians I know, is on guitar. For me, he definitely deserves wider recognition and I feel in some ways that he's right up there with the justifiably celebrated likes of Robert Fripp, Adrian Belew and David Torn. He’s a great and unique stylist with a fantastic dedication to the sounds he produces. Stephen Bennett is on keyboards, Andy Booker is on electronic drums, Steve Bingham is on electric violin and Pete Morgan is on bass. Pete comes from a very different musical background than the rest of us and provides the band with a rooted, earthy sound. Steve Bingham is primarily a Classical musician, but has experimented a lot with loops and sound processes.

You and Steven have already started talking about the next No-Man studio album. What can you reveal about its direction?

Steven’s impulse is that we should make a very, very short album of compact songs. But when you have an idea for a project, it always evolves into something different. This is just a starting point. Both of us are huge fans of ‘60s singer-songwriters such as Tim Hardin and Tim Buckley. Hardin in particular was known for exquisite miniature songs. Very few of his songs were more than two minutes, but had phenomenally sophisticated arrangements with a nice sense of movement throughout. I think in theory we might make an album that echoes and filters the songwriting discipline of Hardin or even Lennon-McCartney through our tastes and influences. In terms of a timeframe, all I can say is that Steven was incredibly pleased with Schoolyard Ghosts and has said he’d like to produce a follow-up relatively quickly. In the No-Man world, that might mean two or three years. We shall see.

CDs and vinyl are increasingly becoming niche markets in the wake of the success of downloading, both legitimate and illegitimate. What’s your perspective on this shift?

You may be right about the niche factor, but Burning Shed is certainly enjoying an increase in physical sales, particularly with special edition CDs and vinyl. I think for artists that I care about, I’ll always go for the physical item, though I listen to most of my music on my iPod. I still buy CDs because they represent better value for money and have better audio quality. Additionally, I'm still a sucker for creative packaging. With iTunes in Britain, if you buy a back catalog album, you get a cover graphic and an MP4 download for about $16. If you buy the remastered CD from Amazon, you get it for between $6 and $10. I’ll always choose the physical product. I can rip it to the computer and have it on my iPod, and I’ll also have the sleeve notes and artwork. If anything, the Internet has changed my buying habits in that I’ll go into a shop, look at the prices and then look online. If the price is cheaper online, I’ll buy it that way or buy it directly from the artist. I think a lot of shops haven’t been just crippled by downloads, but by the fact that there is a greater and cheaper selection of physical product in the online stores.

I think downloads could kill music or at least affect the quality of music, in some ways. The countless leaked copies of Schoolyard Ghosts that appeared on the Web within three days of promo CDs being sent out was a brand new thing for us. I know you can’t stop people from getting music for free. In some ways it’s good because it can encourage people to get excited by new music and then buy it. But breeding an audience that is used to free music is dangerous, especially for a band like No-Man that doesn’t have income from regular live work and isn't funded by a label. We paid for the orchestra on Schoolyard Ghosts ourselves. We took no advance from Kscope in order to get a better deal, a higher royalty rate and keep copyright control—as we’ve done with all our projects since Returning Jesus. If someone downloads the album for free who could have afforded to buy it, it almost certainly has an impact, because we put our own money on the line for this project and a project's financial failure can dictate how much is spent on forthcoming projects. In other words, musical quality could potentially be affected.

Tell me about your forthcoming projects outside of No-Man.

I’ve been working during the last two years with Giancarlo Erra of Nosound. We did a couple of performances in Italy that went very well. I collaborated with Nosound on a track for its last album, Lightdark. The piece “Beautiful Songs You Should Know” from Schoolyard Ghosts is a Wilson-ized version of a song I wrote with Giancarlo. We now have over an album’s worth of material that will emerge at some point. One of the most exciting tracks is called “At The Center of it All.” It features some lovely atmospheric guitar from Peter Hammill, as well as some jazz-oriented upright bass work from Colin Edwin. Work also continues on the next Henry Fool album. We’ve recorded an hour or so of material that seems at least as good as the last album. We're still attempting to beat it into coherent shape. I’ve done some work for Judy Dyble, the original vocalist of Fairport Convention. I’ve contributed some guest vocals to her forthcoming album and I'm also co-producing it with Alistair Murphy. In addition, I’ve continued to write on my own and improvise with other musicians. I have hours of vocal loops that some people think are worthy of release, but as I don’t think they’re something I would buy and listen to, I’m unsure they’ll ever see the light of day. I’m adhering to the same philosophy for my solo output as I am with No-Man in that I’m only interested in putting music out into the public arena that I’m fiercely proud of and that I think I'd fall in love with myself. Releasing things for the sake of releasing things doesn't interest me at all.