Donate to Innerviews

Since 1994, Innerviews has provided uncompromising, in-depth interviews with musicians across every genre imaginable. And it does that with no trackers, cookies, clickbait, or advertising.

Your donations are welcome to help continue its mission of highlighting incredible music and artists, without any commercial considerations.

Your contributions will be instantly transformed into stories and videos, and cover hosting and web management costs. Importantly, your dollars will help ensure Innerviews remains absolutely free to all visitors, independent of their ability to financially support it.

Please consider making a donation today by using the PayPal QR code below.

Phil Manzanera

Perpetual Unfolding

by Anil Prasad

Copyright © 2026 Anil Prasad.

Photo: Hay FestivalPhil Manzanera’s career reads like a travelogue written in chords, rhythms, and endless musical destinations. Best known as the guitarist and a key architect behind Roxy Music’s distinctive sound, Manzanera has spent more than five decades moving between genres, scenes, and roles—performer, composer, producer, and collaborator—in a way that reflects both natural curiosity and fierce ambition. His impact lies not only in his unique guitar approach—often angular, textural, and harmonically adventurous—but in his ability to connect mainstream and experimental traditions while shaping both.

Photo: Hay FestivalPhil Manzanera’s career reads like a travelogue written in chords, rhythms, and endless musical destinations. Best known as the guitarist and a key architect behind Roxy Music’s distinctive sound, Manzanera has spent more than five decades moving between genres, scenes, and roles—performer, composer, producer, and collaborator—in a way that reflects both natural curiosity and fierce ambition. His impact lies not only in his unique guitar approach—often angular, textural, and harmonically adventurous—but in his ability to connect mainstream and experimental traditions while shaping both.

Manzanera joined Roxy Music in 1972 and quickly became a defining force in the group’s blend of glam rock, avant-garde electronics, and sophisticated pop. His guitar work and arrangements helped frame Bryan Ferry’s vocals and Brian Eno’s early sonic experiments on albums such as For Your Pleasure, Stranded, Country Life, and Avalon. Across Roxy Music’s original run and later reunions, Manzanera continued adapting his style as the group shifted from edgy art-rock toward sleek, internationally successful pop without losing its identity.

Alongside his work with Roxy Music, Manzanera built a substantial solo career that enabled him to explore more instrumental, experimental, and globally influenced territory. His 1977 album 801 Live, recorded with a supergroup including Brian Eno, Bill MacCormick, Simon Phillips, and Francis Monkman, became an early example of carefully constructed live recording as an art form. Albums such as Listen Now, K-Scope, and Diamond Head expanded his palette with ambient textures, rhythmic complexity, and a growing interest in Latin and Afro-Caribbean music rooted in his South American background, bringing dance rhythms and melodic forms into dialogue with progressive structures.

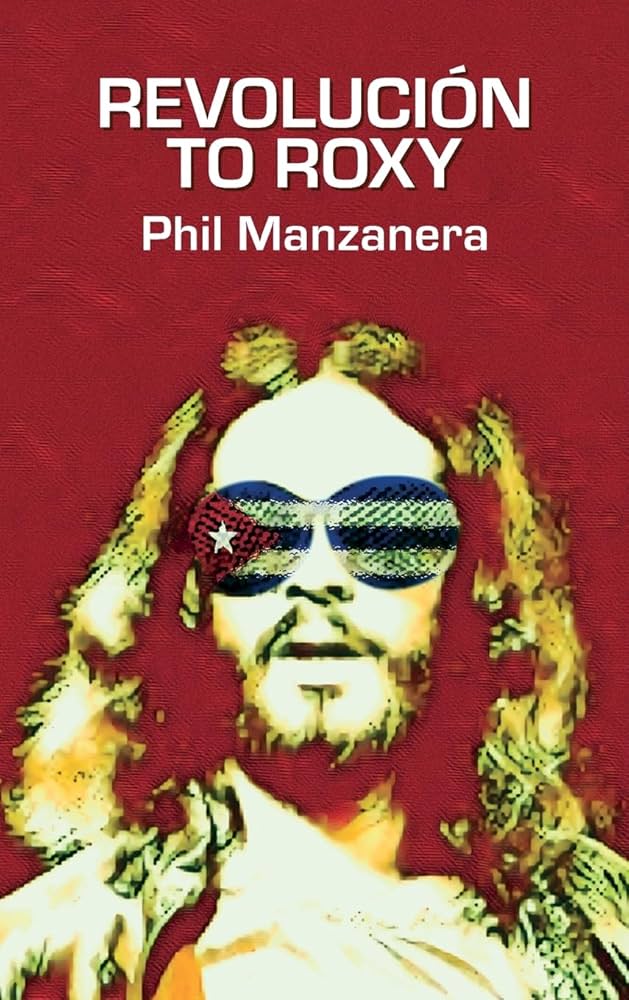

In recent years, Manzanera has turned to documenting and contextualizing this body of work. His recent box set 50 Years of Music assembles material from across his solo career, highlighting both well-known recordings and lesser-heard works, offering a chronological map of his evolving interests. His memoir Revolución to Roxy places that music within the story of his life, tracing his upbringing, his entry into the London music scene, and his collaborations across decades, presenting his career not as a linear ascent but as a series of overlapping creative paths.

Manzanera has also pursued collaborative projects that reflect his interest in political history and global culture. His album series Viva La Taranta explore traditional music from southern Italy, reinterpreted through contemporary arrangements, while The Liberation Project: Songs That Made Us Free combines music with narratives about struggles for independence. These projects illustrate Manzanera’s continuing interest in music as a medium for storytelling, cultural exchange, and historical reflection.

He’s also enjoyed a long-standing musical relationship with New Zealand singer-songwriter Tim Finn, which dates back to 1975 when Finn’s band Split Enz supported Roxy Music on tour and Manzanera went on to produce Split Enz’s debut LP Second Thoughts. Over the years, that friendship translated into musical cross pollination. Finn has contributed vocals and writing to several of Manzanera’s solo records, including appearances on K-Scope and Southern Cross—and ultimately into two fully collaborative albums created during the COVID-19 pandemic: Caught by the Heart and The Ghost of Santiago. Both records, written and recorded remotely across continents, merge Finn’s warm, literate songwriting with Manzanera’s kaleidoscopic arrangements, drawing on rock, Latin, prog, and orchestral influences.

Manzanera’s most recent release, Live in Soho by AM•PM, his ongoing collaboration with Roxy Music saxophonist Andy Mackay, finds him returning to a more intimate performance setting, capturing the duo in a live environment that emphasizes nuance, texture, and interaction rather than spectacle. Recorded in a small London venue, the album revisits material from different phases of his career and presents it in stripped-down form, infused with improvisational elements. Rather than functioning as a retrospective, the record illustrates a musician actively reshaping his past work and using it as a foundation for ongoing exploration and evolution.

Innerviews spoke to Manzanera over Zoom from his home studio in Chertsey, England.

Photo: JC Verona

Photo: JC Verona

Your career in recent years reflects a balance between the archival and a significant amount of new music. How do the two sides of your output inform each other?

I've got a constant desire to do new things and to see what is in this strange thing called the mind. It’s quite a complex piece of human equipment, which at nighttime goes berserk and takes you all over the place in the strangest possible way. And you wake up thinking, “What was that?”

One way of channeling that creatively is in doing music that doesn't rely on you writing it, but rather focusing on improvised music, and just seeing what comes out. And it's always been a bit like that for me in terms of my desire to just play and not think about it, and then see what happens.

Because of the way technology has changed, I can now do that and put ideas down on computer software and then react to them. I'll do that maybe 10 times in a row, and then I'll just listen to it all and see if it makes any sense.

I don’t say, “Right, I'm going to do a jazzy piece” or “I’m going to do an ambient piece." Rather, I just play and then let it take me somewhere. And that has translated into live performances, too. For instance, AM•PM’s latest project reflects what jazz musicians have been doing since the start. But what we do is not jazz. It’s about sounds and textures combining with improvised ideas. We’re having musical conversations. That’s a lot more interesting to me than just being a slave to a song with a conventional structure or simply serving the song. I admire and love listening to others who do that, but I don't necessarily want to do that myself.

Occasionally, this would influence the archival work. When I was putting together the box set and listening back to non-rock stuff, such as 801 Live and Quiet Sun, the self-titled album I made with my pre-Roxy Music band, I began feeling I needed to delve into that area again somehow, which we've done with AM•PM.

We're actually in the process of doing the second Quiet Sun album, which will come 53 years after the first one, which I think will be a big surprise for people. It's 80% done. We just suddenly thought, “We're all about in our seventies. What would it be like if we continued and did a follow-up album now in light of everything that transpired across the last 50 years?”

We started digging and delving around and then found some stuff that was written in 1970. So, most of it is stuff that was written back then. It was down in notation form but was never performed. We started with that and it's evolved into what is coming together now.

Your book Revolución to Roxy begins with an exploration of your childhood borne of dramatic societal unrest and upheaval. Describe the process of unearthing and writing about that period.

You get to a certain age in your life that makes you want to make sense of what happened in it. When I started doing the book, I was 69. Both of my parents had died many years ago. I began to regret that I didn’t ask them more questions. That led me on an exploration, really. I then started discovering more and more things about my life. And even since I finished the book, I've discovered more incredibly new things about my grandfather on my father's side. I learned my father was illegitimate. And then we discovered only recently that his father was actually a Neapolitan musician from a place called Cava de' Tirreni. So, it relates to the questions of “Why do I do what I do?” and “Is there any genetic reason?” I have two Italian grandparents who are musicians. My mother started teaching me guitar in Cuba in 1957. So that's more like nurture rather than nature. I'm trying to make sense of it all.

I did the book not just for me, but also to leave a little story for my many grandchildren and loads of my cousins. I have 70 in Colombia, where we all came from. That was primarily the motivation for doing this memoir. Of course, I was in a rock and roll band, so obviously I'm going to put stuff about that in it too. But the most interesting bit for me was about the family and tracing its origins.

Another thing I discovered the other day is that I am related to a Jamaican artist named Sean Paul. His real name is Francis Henriques. My grandmother's name was Henriques. I'm in the process of getting in touch with Sean Paul and saying, “You're not going to believe this. I think we're related. Maybe we should do something together.” So, this process of discovery just goes on and on. And it's just so much fun, quite frankly.

The book discusses what you experienced as it relates to revolution, war, and insurrection, and also frames it within an existential context. Did you derive any specific philosophies or perspectives that impacted your life as a musician?

I was there when the Cuban Revolution happened, so Che Guevara became like a folk hero. I read about Marxism and socialism. I became an expert on everything to do with Cuba and the Cuban Revolution while I was at school. And that chimed with what was going on in the ‘60s in London in terms of revolution and change.

People were looking to all these different philosophies with a huge blossoming of different thought patterns. My friend Ian MacDonald wrote the book Revolution in the Head: The Beatles' Records and the Sixties. He was part of my upbringing. It talks about the revolution in the head that was occurring in many senses in the ‘60s. And my being informed by that knowledge of the ideas of Marxism, pre-Stalin, was very similar to the hippie philosophy of the ‘60s that came out of the West Coast of the US. It was about peace and love, which sounds a bit drippy now, but stayed with me.

The ideas of togetherness and working together with people are things I took into bands and musical contexts. I was always interested in bringing together people from different countries and different styles of music to find a common thread. So, it’s all tied up with what happened to me in 1967 until I joined Roxy Music.

We're currently living through a period of dramatic societal unrest across the world. What are your thoughts about the value of music in the current environment?

In moments of despair at what the hell is going on in the world, you can just think it’s gone to hell in a handcart. You ask questions like, “What’s my function?” and “What can I do to help?” I’m not a politician or activist, but I’ve been to a few marches. All I can do is try and help sooth people’s anxiety with music and deliver some sort of meditative usefulness.

I’m not chasing chart success. I’m just making music that helps. I know music is good for your mental health. Having been brought up in South America, despite all the trouble, trials and tribulations, people could still dance away there. They’d forget about their problems for a bit, and it gave them relief. That’s one of the great things about Latin music. The rhythm, groove, and sentimentality are almost their equivalent of the blues. It’s cathartic. If I need help in justifying me sitting in my studio and creating new music, Latin music helps.

I hope my music has some resonance with people. The thing about me is that what I do isn’t necessarily about technique. It never has been. I decided when I was 17-18 that I wanted to do music for the rest of my life. I wanted to do it gently, slowly, enjoy it, and learn a lot. There are still so many things I want to learn how to do, which I probably never will be able to do. But I’ve always wanted to spread the music out and luckily, through a few of the bands I’ve been a part of or produced, some of them have produced income that allows me to continue doing that.

What are some musical areas you'd like to further explore?

I’ve always wanted to be able to play rumba flamenca. I’ve tried so hard and that groove should be in me. When I produce Spanish bands, the guitarists can all do it, as well as rock. So, I’d say, “Right, I’m going to sit you down. I’m going to film what you do with your right hands. And then I’m going to study it and learn how to do it myself.” But I still can’t do it properly.

I’m also in awe of people who have technical prowess, especially those who mix what they do with flamenco styles. That’s not something you just pick up and put down. It’s a lifestyle. You have to commit yourself to doing it. But I’m too much of a sort of scattergun type of person to have done that.

What story do you feel the 50 Years of Music box set conveys?

It’s a soundtrack to my musical life outside of Roxy Music. The box is about putting together all the different styles I’ve been involved in and the attempts to do new music across my career. They’re called solo albums, but they’re not really. They’re an excuse to work with friends and to not be controlled by some A&R department somewhere. They’re about doing whatever you want.

I formed my own record company in 1989 so I wouldn’t have to ask permission from a label to make an album. But from the beginning, Roxy Music members started doing solo albums, including Bryan Ferry, Andy Mackay, and Brian Eno. I worked on quite a few of them. Two years after the solo albums started, I put my hand up and said, “Can I do one?” And they said, “Oh yes, go on. Just do it.” So, I did two straightaway—Quiet Sun and Diamond Head.

I worked with Robert Wyatt, who’s one of my heroes and someone I’ve known since I was 16; John Wetton, who was a good friend; Paul Thompson; Simon Phillips; and the MacCormick brothers on them. We just had fun.

Photo: Suki Dhanda

Photo: Suki Dhanda

The box set vividly illustrates the elasticity of rock and pop, and the potential of stretching boundaries as far as they can go. What are your thoughts on that?

Yeah. It shows how technology changed across 50 years. I was always very much up on it. Right from the beginning, Brian Eno and I bonded in the sense that we were both keen users of any new gear that came up. We were there when they invented a four-track cassette recorder. There was also a time in the ‘70s when there was only one fuzz box and wah-wah pedal. So, we had to come up with unique ways of creating weird and wonderful sounds, organically. We’d stretch a tape around a broom handle and put a little sticky tape on it. One thing led to another.

If you start from the beginning, it’s a series of yes and no questions. "Do I do this? Yes. In that case, do I do this next? No." It was about critical abilities and the craftsmanship of using a musical palette to draw from.

When people want advice on creativity, especially young kids, I say “Listen to as much and as many different kinds of music as possible, because you will then have all this stuff to dip into when you are painting your picture.” It gives you all of these colors to use. And that will help you create your own particular combination of elements and express your unique point of view as an individual.

I’m not against music colleges and schools, because they’re primarily to do with classical music and playing the music of the great masters. But I also see a disadvantage, because a lot of classical musicians who play Mozart or Vivaldi can’t improvise. They’ve got this incredible technique which I feel could be utilized in such an interesting, new kind of way. But they’re trained to do things in a certain way.

The whole improvisational thing really influenced me in the mid-‘60s—including the Grateful Dead, The Velvet Underground, Miles Davis, and John McLaughlin. I read McLaughlin turned up to a Davis session and had no idea what he was going to play. He wasn’t given any instructions. And that way of working is something I’ve used as a template. I like recording a whole bunch of stuff and then sifting through it, panning for gold, and then putting things together in different ways. Davis was doing that in the ‘60s, putting together different takes, cutting up tape, and working with great engineers to do it. I loved that kind of ambition.

Did anything surprise you during the process of listening back to 50 years of output?

When I heard some of it, I thought “Oh, that’s good.” But then for a lot of it, I also thought “That’s really average” or “Why did I do that?” But I was collaborating on all of it, apart from the instrumentals, with my friends like Brian Eno, John Wetton, Robert Wyatt, Tim Finn, and Neil Finn. Most of the music had to do with songs. That’s why a couple of years after the Roxy Music farewell tour, I sort of said “Farewell to songs.” Since putting the box set together, I decided that I’m looking forward and don’t want to look backwards too much at all.

Manzanera and Andy Mackay perform with Roxy Music, 2022 | Matthew Weber

Manzanera and Andy Mackay perform with Roxy Music, 2022 | Matthew Weber

Discuss the journey from the AM•PM studio album to the concert release, and the evolution of the material the latter reflects.

Like so many musicians during the COVID-19 pandemic, I was stuck at home. I had a keyboard, one guitar, and an amp. I wanted to do some music. Then I thought, “What’s Andy doing?” He was in a place called Brighton on Seaside, so I rang him up and he said, “I’m not doing anything.” I said, “Well, you should be doing music.” So, I sent him some tracks to work on. I told him, “Do whatever you like, send it back to me, and we’ll go back and forth.” That’s how things worked.

After COVID-19 finished, there was a chance to do a Roxy Music farewell tour, and we went on the road. We finished it and then immediately we finished the AM•PM album. We said, “Let’s take this improvised stuff, go in the studio and complete it. We’ll get Paul Thompson on drums.” Because we had played and rehearsed for ages for the Roxy tour, we had great chops. We were able to work fast.

Once we mixed it and listened to it, I thought, “I can’t quite describe what this music is.” That’s because it’s improvised and it changes quite a lot, even within each track. I felt it was going to be difficult for people to review because most music journalists are literal people who are very happy to have songs with lyrics, because they can sink their teeth in. But when it comes to talking about instrumental music, there’s a problem. They don’t know how to describe it if it doesn’t have any resonance for them, or it seems sort of abstract in a floaty way. And a lot of the reviews did say, “We can tell you what it’s not, but it’s very difficult to tell you what it is.”

I decided I liked this reaction. Then Andy said, “Why don’t we do some live gigs?” I was worried. I thought it was going to be a disaster. It felt too complicated. So, I said “Can we not do it?” And then we decided to make it a small thing. The last time we played together was at the O2 to 20,000 people with Roxy Music. We decided to do play with AM•PM to 75 people each night across three evenings at a screening theater in Soho in London. It had 7.1 surround sound, so we tried to turn it into a ‘60s-inspired psychedelic event. I made some videos, which were projected onto us. We took a minimal amount from each track and used it as a basis for improvising.

Every time we played, it was different. We were just in the moment and saw what would happen. We had virtually no rehearsals. Technically, it was an amazing summation and culmination of 50 years of technology. Our mixing guy was triggering stuff from the desk and sending it around the 7.1 speakers. And then we’d react to what was being played as we listened to each other. It worked really well and you can hear it on the live album. You’ll hear space. You’ll hear sounds appear that don’t sound like guitar playing. It really reflects our little collective of musicians and the complex series of interactions as we were dealing with sounds, textures, and grooves, rather than blowing in a more technical way. That combined with the light show into an immersive scenario.

I recently heard Eno’s new music with Beatie Wolfe, and it’s related to what Andy, Paul, and I are doing. Bryan Ferry also did an album with a performance artist named Amelia Barratt called Loose Talk, which is in the improvisational realm. It gives me great pleasure that all the original members of Roxy Music are still holding to the original mission statement, which is to create avant-rock music. In fact, when I answered an ad to join Roxy Music, it said they were looking for the perfect guitarist for an avant-rock group to create original, creative, adaptable, melodic, fast, slow, elegant, witty, scary, stable, and tricky music. And that actually does describe the music we’re doing now.

You mentioned the AM•PM intersections with the 2022 Roxy Music tour. Talk about using AM•PM as a vehicle to reinterpret Roxy songs like “Out of the Blue,” “Love is the Drug, and “Tara.”

Even though it was meant to be an improvised scenario, I thought it might be too much for the punters to listen to 90 minutes of ambient music. I thought we better give them something they know during the last 20 minutes but change the arrangements. They’re sung by Sonia Bernardo, and we’ve got the amazing violinist Anna Phoebe on violin, who was in Roxy very briefly as well. So, we thought “Let’s kick some ass for the last 20 minutes. You put up with us for an hour of this avant music, and now we’ll give you some Roxy stuff and show you we can rock as well."

Roxy Music, 1972: Phil Manzanera, Bryan Ferry, Andy Mackay, Brian Eno, Rik Kenton, and Paul Thompson | Photo: Island Records

Roxy Music, 1972: Phil Manzanera, Bryan Ferry, Andy Mackay, Brian Eno, Rik Kenton, and Paul Thompson | Photo: Island Records

How do you look back at the 2022 Roxy Music reunion?

It was the first time we were able to present Roxy’s music within an iconographic context because of the video screens we had. I was very pleased about that. They showed a lot of artwork, imagery, and visual context for the shows. So, it worked on two levels.

The tour wasn’t easy to make happen because of COVID-19. Bryan also wasn’t particularly well for the tour, and we hadn’t played concerts for ages. It had been years and years. So, it was a big undertaking.

Another issue is we didn’t have a manager. Bryan lives near me and just rang me up and said, “Fancy coming around for a cup of tea?” And then he said, “Fancy doing a farewell tour?” I said, “Sure, let’s do it. But hang on, we haven’t got a manager. We haven’t got an infrastructure. We haven’t got an office." So, we had all of that kind of stuff to sort out, but I’m so glad we did it.

We recorded and filmed the tour. None of that’s come out, but it should come out at some point. We need to get on with it, but we’ve all been too busy doing new things. There’s a fear we’re going to run out of time, but it’s there.

The tour was a legacy thing, and I was very happy with it. At the end of the O2 final gig, Andy and I said, “You know what? Let’s stop. Let’s not do anymore.” In fact, we only did 12 concerts across the whole world.

Another key creative vector of yours is your recent work with Tim Finn on Caught by the Heart and The Ghost of Santiago. That relationship goes all the way back to Listen Now and K-Scope, as well as your work as a producer for Split Enz. Discuss the reemergence of that partnership and how the two albums you did in recent years showcase the distance traveled.

Ever since I first saw Split Enz for the first time in 1975 during Roxy’s first tour of Australia, I thought they were cool. I was absolutely blown away. And then they happened to be the support band at the next night’s gig. So, I stuck my head around their dressing room door after watching them and said, “You guys are amazing. Let me know if there’s anything I can do to help the band.” They said, “Will you produce our album?” They didn’t have an album at that point. I thought, “Yeah, dream on.” I was going back to London, and I had no idea how that could happen.

So, they recorded their debut album Second Thoughts in Australia, but they came to England as well, and we re-recorded some tracks there, together. Second Thoughts was one of my first productions after co-producing with Brian Eno and John Cale. I had my mind on the 801 Live project. The Finns attended the recording of it at Queen Elizabeth Hall in 1976. That album is actually 50 years old and has been reissued as a deluxe edition.

Tim was just over here a few months ago. I hadn’t seen him physically for six years. It had just been on Zoom. We had a lovely time chatting about those times back then. We’ve been friends ever since. Both Tim and Neil Finn are just great people, and they’ve just got it as singers, songwriters, and lyricists.

When Roxy Music got inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2019, Fleetwood Mac were also there being honored. And by that point, Neil was in Fleetwood Mac, performing Lindsay Buckingham’s parts. He invited us to a party afterwards. We had our picture taken, which I sent to Tim. I said, “Look who I bumped into last night.” He replied, “I’ve been meaning to get in touch because we want to do some weird versions of tracks based on the first Split Enz album. Would you play guitar?” So, that’s how we reestablished working together again.

During COVID-19, Tim was sitting at home and said, “Have you got any Latin groups I can write for?” I said, “You’ve come to the right place. I’ve got a whole computer’s worth of material.” So, I’d send him stuff and the next morning, he would send it back with a vocal and lyrics. I thought, “Hang on, how could you possibly do that so quickly? Do you have a book somewhere of lyrics you just adapt?” Every morning, I’d walk around the field here at home, because we weren’t allowed to leave our homes, and I’d listen to the stuff he’d sent overnight. It was just amazing. I realized how incredible Tim is.

The way Tim and I worked is also how we worked with Roxy, in which we’d do all the music first, and then we’d write a top line over it with lyrics. I’d say 95 percent of Roxy tracks were done that way. It also wasn’t like that for David Bowie until Brian Eno came along and showed him the Roxy method of writing stuff. Eno would create a musical context that someone can inhabit.

I told Tim I could change stuff if he wanted, but he said, “Don’t change anything. I’m just gonna work on what you sent me.” In the end, we did about 20 tracks over two albums. It was very enjoyable and helped get me through the COVID-19 period.

Manzanera live at Gibson Studio, London, England, 2015 | Photo: Brian Rasic

Manzanera live at Gibson Studio, London, England, 2015 | Photo: Brian Rasic

Let’s revisit your 2015-2016 Viva La Taranta releases. Tell me how you arrived at the elaborate scope they explore, and the creative process involved in realizing them.

Two guys came to me and asked me if I’d be interested in being the musical director of a free concert in Melpignano, Italy in August of 2015. They said the event was all based on Pizzica music, but they wanted me to bring a new flavor to it. Pizzica music is from the Puglia region of Italy. They try to reinvent it every year with a new musical director.

I foolishly said yes. I had six months to work with what they call a popular orchestra, which includes all kinds of instruments including bagpipes made with pig bladders, tamburellos, and people playing one-man drum kits. I had to learn all about this music and even went back to Alan Lomax’s field recordings. He was sent to Puglia by the BBC in the early ‘50s to chronicle this music.

This kind of Pizzica music was based on the ancient Greek Dionysian rites that go back 2,000 years. It evolved out of trying to exorcise demons from people who had been bitten by tarantulas in the tobacco fields. So, this sort of 6/7 rhythm played on the tamburello was meant to build up into a frenzied groove for exorcising demons.

Eventually, this music converged with what happened in the history of that area. It was invaded by the Turks, the Greeks, and the French, among others. So, the music went on to incorporate many influences like a melting pot. The area also has two kinds of mafia organizations, which I didn’t appreciate. There were all kinds of levels of intensity going on at the time, including a political election.

I was able to invite guests, so I had Tony Allen on drums, Paul Simonon from The Clash on bass, a Columbian singer named Andrea Echeverri from a band called Aterciopelados that I produced, and the most famous rock musician from Italy named Luciano Ligabue. Everyone had to sing in the dialect from the region. And it was going to be performed in front of 200,000 people who wanted to dance, as well as aired on the Rai 1 television network.

This was also occurring in between me co-producing the David Gilmour album Rattle That Lock. So, while working on that, every month I’d also go to Italy to rehearse with the orchestra and 18 dancers dancing the famous Taranta. I’m exhausted just talking about it. I don’t know how it happened, but it was great, and I came out of it alive.

I thought, “I’m going to record this, because I spent all this time doing this.” So, we released three albums worth of Pizzica music. It was like nothing else I’ve done before.

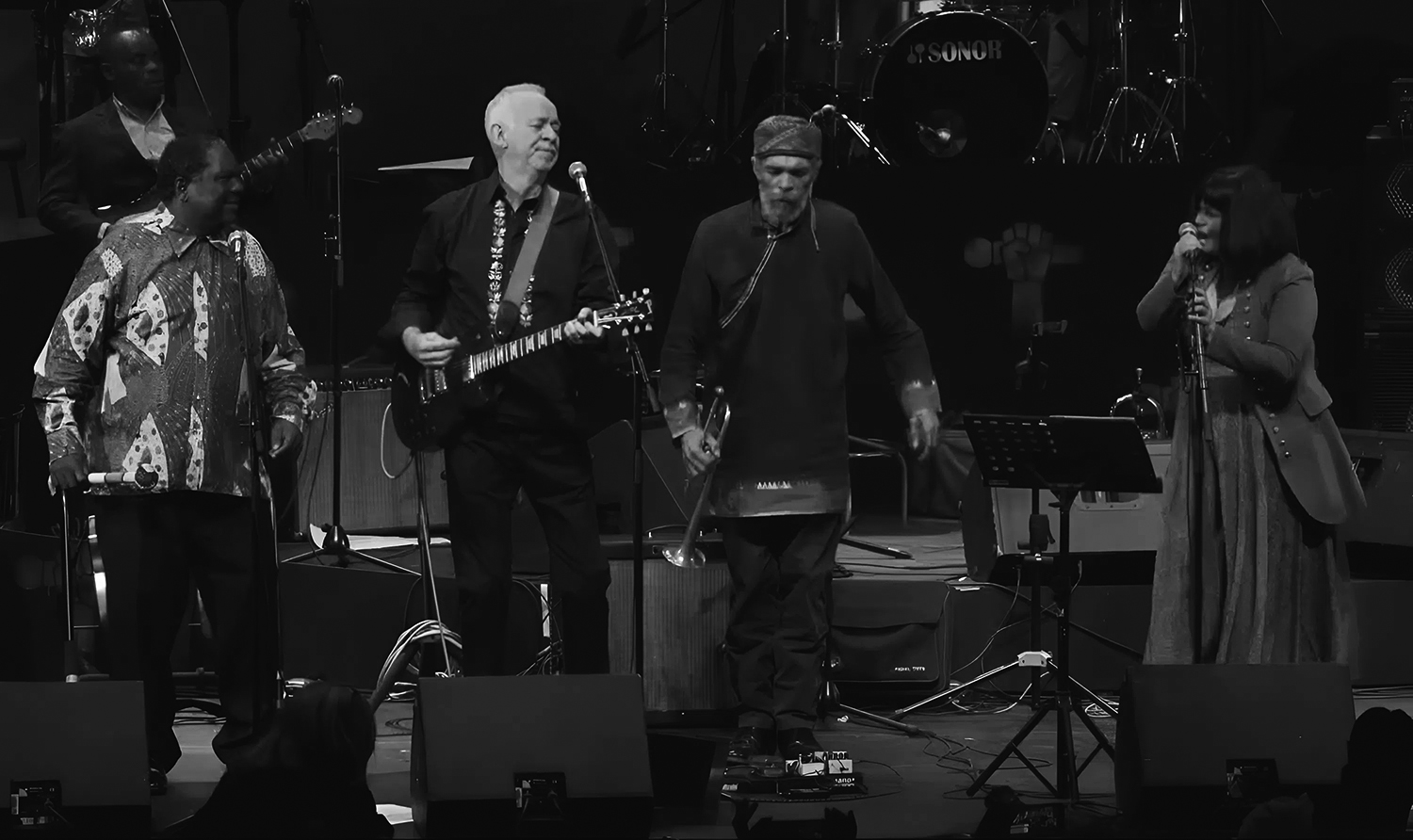

Manzanera in concert with The Liberation Project at the Africa Month Festival, Johannesburg, South Africa, 2018 | Photo: Africa Month Festival

Manzanera in concert with The Liberation Project at the Africa Month Festival, Johannesburg, South Africa, 2018 | Photo: Africa Month Festival

You rapidly followed that up with another expansive collaboration titled The Liberation Project: Songs That Made Us Free in 2018. How do you look back at it?

That all started because years ago I was invited to be part of a South African band called the African Gypsies that was going to play at WOMAD. Funnily enough, the main mover in the band was a South African guy who’s of Italian descent. We also had Ray Phiri, who’s the guy who helped Paul Simon do Graceland, and other incredible musicians from South Africa.

So, I did that WOMAD tour with them and we played Las Palmas, South Africa, Australia, and New Zealand. Through that, I became very friendly with people from Durban, South Africa. I kept being invited back to work on different projects there.

The Liberation Project was something put on to commemorate Mandela Day in Cape Town, South Africa, and then it went on tour in Italy. Mandela’s daughter would come on and talk before the show. One of the main concerts in Italy was fabulous. They invited people from all over the world to be a part of it. So, it was another great opportunity to play with very different musicians with a different groove. Again, I learned so much and appreciated how there are just so many amazing musicians from different countries.

In the ‘60s and a lot of the ‘70s, things were very European and American-centric everywhere, until The Buena Vista Social Club came along and was a big success. Then Peter Gabriel helped showcase that every country has some amazingly unique music they express themselves through. And now we combine elements from all sorts of different countries.

I also realized that people who understood Spanish could also understand what people in Argentina were singing about. It’s just brilliant. And so is Columbia, Puerto Rico, Venezuela, and Brazil. When you know the language, you can more deeply appreciate their art and craftsmanship. So, it’s been a part of my whole thing to use music as a vehicle to bring people together.

Manzanera and Brian Eno perform with 801 Live at Reading Festival, England, 1976 | Photo: Reading Festival

Manzanera and Brian Eno perform with 801 Live at Reading Festival, England, 1976 | Photo: Reading Festival

801 Live from 1976 was another all-star project with very serious ambitions. What are some key memories that stand out for you when you think about it?

Brian Eno, Bill MacCormick and his brother Ian MacCormick, also known as Ian MacDonald, went to a little cottage in Wales and cooked up the idea of doing this project, which would only last, by definition, six weeks.

The idea was we’d get people who love technique and people who hated technique together. And through our joint music and a couple of covers, we’d attempt to bring this all together in one package. So, we had an 18-year-old incredible drummer named Simon Phillips, who’s now a total legend. We had a technically-brilliant multi-instrumentalist named Francis Monkman, who had been with Curved Air and played with John Williams in Sky. We had Lloyd Watson, a blues guitarist who had won the Melody Maker competition for solo artist of the year. He had been supporting David Bowie with his slide guitar playing. And then we had Eno, who was anti-technique, and me in between, straddling the two perspectives.

We went to the rehearsal room for three weeks and then we went and played only three gigs. It was meant to be five, but the other two got cancelled. We played a tiny little pub, the Reading Festival, and Queen Elizabeth Hall, which we recorded. We used Island Mobile to capture it, but didn’t use it the way most people would to record a live album. We used a lot of ambient mics out front and close mic-ed everything. So that made it much more like a live studio album. Then we mixed all this music together, and by some miracle it worked, and then it was over.

Literally, after that, Eno went off to work with Bowie, and we virtually never saw him again. It was one of those things. It was a great, great thing that was designed to only last six weeks and then in a puff of smoke, it disappeared.

John Wetton and Manzanera, 1987 | Photo: Tony McGee

John Wetton and Manzanera, 1987 | Photo: Tony McGee

I’ve seen little discussion about the 1987 self-titled Wetton/Manzanera album over the decades. Tell me how it came together.

John and I have been friends since we were stablemates from 1970 onwards. King Crimson and Roxy Music also had the same management, so I got to know him very well. We would go on holidays together.

When the opportunities came up to work together, when he wasn’t working on all these other things, we’d do stuff. Eventually, I had a studio and we said, “You know, we see each other a lot. Why don’t we just do an album to get some songs down?”

John wanted to do an album of songs, not of instrumental or tricky music. He was in the post-Asia phase. He had a lot of success with Asia by that point, and then it had gone horribly wrong.

He was drinking a lot, then. So, I said, “Okay John, let’s do this album. We’ll write the songs as we go along.” Unfortunately, he would only last a couple of hours before he would fall asleep. So, it was a bit difficult.

We were trying to be commercial and use his beautiful voice. We had Alan White and Carl Palmer come in and play some drums. We were sort of pleased with it.

Ahmet Ertegun at Atlantic was interested in releasing it. But there was some contractual issue, and John was stuck with Geffen. I think during some interview in America, John had said some bad things about Geffen.

My manager at the time also handled Pink Floyd and his manager at the time also dealt with Yes. There was a meeting about the record at Geffen in Los Angeles. I said, “John, don’t go to the meeting.” He went and waited outside. The big dogs went in to do the deal. It all ended very, very badly. And then I got a call from John and he said, “It’s all gone horribly wrong. It’s going to be on Geffen, but they’re going to kill it.” So, it never really stood a chance. There were a couple of singles on it that could have done well in America but it was buried.

I remained in touch with John until a couple of weeks before he passed away in 2017. By then he’d given up drinking. I said, “John, I just want to tell you, you’re an amazing bass player and singer.” I knew him before he joined King Crimson, back when he was in Family. He was one of the few people in England who could do that Sly and the Family Stone slap bass playing. And regardless of what the sound was on stage, he could sing in tune and play bass at the same time. He had incredible talent. He was a joy to play with.

You’ve participated in virtually every music business shift that’s occurred for decades. What are your thoughts about where the industry has landed?

The whole paradigm of the industry has changed. It is in a state of flux. Nobody knows what to do to get anywhere. Young musicians come to my studio for advice. I listen to their stuff and I’ll say, “This sounds great. What more do you have to do?” So, making music has become very democratized, which is great. When I started in Roxy Music, there were very few people in London trying to start music careers.

Back then, there were very few media outlets, and there was no Internet, obviously. Word of mouth accounted for things. But now, it’s terribly hard for musicians to earn a basic living to pay their rent. Most young musicians around London have to do about five different jobs to have the privilege of being a musician. It’s very difficult now.

I use streaming. I love the fact that I can listen to stuff without having to go buy the album. However, they need to pay the musicians a proper rate. But it’s all controlled through a series of non-disclosure contracts between the multinational corporations and the streamers. And we’re all screwed, basically.

Where’s the revolution? This is political. The only way to sort it out is by legislation. There are so many vested interests involved, like so many things in society. There are so many greedy people.

If one looks historically at the whole record business, since the dawn of record companies, unfortunately, the narrative has always been, “Let’s pull one over on the musicians. Let’s get their copyrights and screw them over.”

There have been some genuine people who love music and musicians, but to actually affect change, it has to become political, whether it’s through Congress or the Houses of Parliament. We know what the issues are. That’s my summation of where we are at the moment.

Tell me about your personal drive to remain creative, active, and moving forward at this point in your life.

I find it helpful for my physical and mental state, just like I find going swimming or for a walk in the countryside, looking at nature helpful. So, it’s self-help, really. I have a way of getting it out to people using the current state of technology. So hopefully it has some resonance for other people. Ultimately, it’s just helpful.

Watch the video podcast version of the interview: