Donate to Innerviews

Since 1994, Innerviews has provided uncompromising, in-depth interviews with musicians across every genre imaginable. And it does that with no trackers, cookies, clickbait, or advertising.

Your donations are welcome to help continue its mission of highlighting incredible music and artists, without any commercial considerations.

Your contributions will be instantly transformed into stories and videos, and cover hosting and web management costs. Importantly, your dollars will help ensure Innerviews remains absolutely free to all visitors, independent of their ability to financially support it.

Please consider making a donation today by using the PayPal QR code below.

Pukka Orchestra

Serving the Story

by Anil Prasad

Copyright © 2024 Anil Prasad.

Pukka Orchestra, 1984: Tony Duggan-Smith, Graeme Williamson, and Neil Chapman | Photo: Pacemaker/Cadence

Pukka Orchestra, 1984: Tony Duggan-Smith, Graeme Williamson, and Neil Chapman | Photo: Pacemaker/Cadence

During the early-to-mid-‘80s, Pukka Orchestra’s brand of provocative pop was a key highlight of the Canadian music scene. The trio, comprised of singer-songwriter Graeme Williamson and guitarists and co-songwriters Neil Chapman and Tony Duggan-Smith, scaled impressive heights with a run of successful singles, including “Listen to the Radio,” “Might As Well Be On Mars,” “Cherry Beach Express,” and “Rubber Girl,” as well as its revered 1984 self-titled debut album.

The band’s output was largely based on Williamson’s superb songcraft. His inventive turns of phrase focused on incisive and inspirational subject matter that explored the intersections between the personal and the global. Chapman and Duggan-Smith contributed sophisticated, creative arrangements to the tunes that further elevated their intrigue and resonance. The combination meant Pukka Orchestra's output stood tall above the generic new wave acts that crowded the era’s pop universe.

After Pukka Orchestra’s initial high-profile visibility, several factors converged that prevented it from achieving significant further traction. Its original record label, Solid Gold, unexpectedly folded in 1985. Simultaneously, Williamson suffered kidney failure while on a trip to Scotland with his wife. They chose to relocate from Toronto to Glasgow, where he pursued treatment.

Williamson, Chapman, and Duggan-Smith continued working together. They would occasionally meet in Toronto and Glasgow for songwriting sessions. Eventually, two further Pukka Orchestra releases emerged: 1986’s The Palace of Memory EP and 1992’s Dear Harry album. The trio chose to release them independently after the disillusionment and legal entanglements caused by the demise of Solid Gold. However, the band was unsatisfied with both efforts. They were awash in ‘80s synth-pop elements with the group’s guitar prowess relegated to the background. The collective feeling was though they were full of strong songs, the production philosophy worked to their detriment.

The band quietly faded away after Dear Harry. Williamson had a liver transplant in 1997 after he contracted hepatitis C from a blood transfusion. He then attended the University of Glasgow for a MA in English and French, and University of Strathclyde for a postgraduate degree in creative writing. Williamson went on to become an author. His novel Strange Faith was published in 2002 on both sides of the Atlantic.

Chapman established himself as a first-call session musician, and released several solo albums, including Hollywood World, Hope in Hell, and Gitar. Duggan-Smith became a set designer working primarily on American films and television series shot in Canada. He then returned to instrument making, having apprenticed with luthier Jean Larrivée before Pukka Orchestra formed. Chapman and Duggan-Smith also co-founded two other bands during the 1990s and 2000s: Autocondo and Neotone.

Even though Williamson, Chapman, and Duggan-Smith had all moved on from Pukka Orchestra, they remained close friends until Williamson tragically died in 2020. Two years after his passing, his widow Iris Williamson and Chapman made it their mission to complete the more than 30 solo songs he had written and recorded that had never been heard by the public.

“Graeme wrote all his life,” said Iris. “Despite his chronic bad health, he has left an incredible body of work which I am trying to share. I think he is an important voice: true, compassionate, and honest. His motivation never left him. He had to write about the world he saw. Graeme’s songs are a reflection of his views on injustice and those who are neglected and invisible in our society.”

The first batch of songs were produced in 2022 and are featured on a forthcoming Graeme Williamson solo album titled Because You Were There. A follow-up LP is currently in development.

Both Iris Williamson and Chapman consider Because You Were There a significant achievement. It led them both to consider the idea of revisiting Pukka Orchestra’s material from The Palace of Memory and Dear Harry. The idea was to rework and update those tracks with more guitars and loops, and enable them to have a second life. Together with Duggan-Smith, they realized the complex project, and the result is 2024’s Chaos Is Come Again, the first Pukka Orchestra LP in 31 years. It was released on Pacemaker/Cadence Records, with the help of Frank Davies, the same publisher who first brought Pukka Orchestra to public attention with its debut album.

“Graeme is not here to be involved in the project, which is heartbreaking, but Neil knows Graeme’s tastes very well and I think Graeme would have been happy with the additions to the tracks,” said Iris. “It’s my hope that both original fans and a new audience might hear and identify with the songs.”

Innerviews discussed the making of Chaos Is Come Again and Because You Were There, as well as the history of Pukka Orchestra, with Chapman and Duggan-Smith during a Zoom conversation.

Pukka Orchestra, 1984 | Photo: Pacemaker/Cadence

Pukka Orchestra, 1984 | Photo: Pacemaker/Cadence

Talk about the beginnings of Chaos Is Come Again and how it turned into a full-blown Pukka Orchestra album.

Chapman: We were first working on Graeme’s posthumous solo album Because You Were There. It was a case of diving into a pool of a million tears.

We had received all his songs he wrote over the last 35 years of his life that were on his computer in Glasgow. While he was still alive, Graeme, Iris, and I organized and put everything together in one spot. There were so many great songs. He was such an amazing writer.

After Graeme died, we said, “Let’s do an album for his legacy.” So, we focused on songs with him playing guitar and singing. They were all on one track and I couldn’t separate the guitar from the vocal, but through the magic of technology, I was able to take those songs, and with the help of programmer Mark Alexander, apply a tempo map to them. We then added band tracks on top of them, creating a new “group album” based around his previous solo recordings.

While I was doing that, Tony said, “Why don’t we revisit the latter-day Pukka Orchestra stuff, just for fun? Let’s see what we can do with that material, too.” We got Iris and Frank Davies on board and so began the birth of Chaos Is Come Again.

We went back to the recordings for Dear Harry from 1992 and The Palace of Memory from 1986 and thought about how we could better represent them. Those two releases were a product of the ‘80s, when things were very synth focused. I think I can also safely speak for Graeme when I say we all never really connected with those versions.

The songs were great. The three of us wrote them in Glasgow. Graeme did all the lyrics. So, the basis for the songs was really strong. The overall production was really good, too, with the tracks captured by engineer Tom Atom using an old Neve board and a Studer recording setup. Everything should have been great, but we realized that the guitars were deemphasized in favor of keyboards. So, there’s very little guitar, even though we’re all guitar players.

The big issue with the songs was we didn’t have the original multitracks. So, what I did was take the master recordings, and similar to what I did with Graeme’s solo work, used the magic of technology to add new elements, update the songs with more guitars and put in some cool loops to make them more contemporary.

When we listened back, we went “Wow. This is the way it should have always been.” We realized the soul of the songs—for us, anyway—was always in the guitar groove and, of course, Graeme's voice and lyrics.

After we worked on several songs, we felt “Why don’t we put these out as a new Pukka Orchestra album?” And that’s what we have done.

You released Dear Harry and The Palace of Memory independently through A Major Label, your tongue-in-cheek indie label. Both disappeared pretty quickly. Elaborate on what happened.

Chapman: A Major Label was our little joke name. We wanted to be fully independent in the aftermath of the Solid Gold Records label experience that followed the release of our debut album. It was a case of “What label are we going to be on? Well, a major label, of course!” [laughs] But at the end of the day, we didn’t think either of those releases were what we knew they could be.

Duggan-Smith: I’m not quite as harsh about them, but the reality is, as Neil said, we’re guitar players. The way we think about music is in relation to strings. But on the original releases, you’re hearing so much synth all over them. Those elements really shortened the shelf life of the production and dated it. It also got weighed down by strange gated reverbs from the era.

When we originally recorded those songs, we were going back and forth between the U.K. and Toronto. We’d make plans about getting together for a month, but then Graeme would become ill a lot because of his transplants and concerns about his immune system. Every time we’d get plugging away on tracks, Graeme would have to leave for medical treatment. This was spread across a number of years, not just months. So, the way everything was put together was chopped up over many periods.

I think the way it all came together meant we would never have the same relationship to those tracks as what was on the debut album. We also didn’t know what the future held for Pukka Orchestra and for Graeme’s health.

Chapman: I honestly couldn’t get behind this music when it was originally finished. I always felt “What a shame we put this stuff out and it’s not up to par.” We overlooked our biggest strength, which is guitars. I felt “If these tracks don’t excite us, it’s not surprising they didn’t do it for anyone else."

For instance, take “Keeping Warm in the Cold War.” It had great lyrics, drum, bass and keyboard parts. But again, it was missing guitar. I added a rhythm guitar part that I feel brought the track to life. That happened across all the songs. I’d add some electric parts, Tony would add acoustic parts and jangly bits, and they would spring to life.

Discuss the creative process involved in realizing these new versions of the songs.

Chapman: Dear Harry and The Palace of Memory were recorded at Enormous Sound studios in Scarborough, Toronto with the great Tom Atom engineering. Even though I wasn’t happy with the instrumentation, they did sound great.

What I did was take the master recordings and put them into Logic Pro. I added guitars and by creating a tempo map added some loops as separate tracks. If you consider the original master recording a single stereo track, I might have added as many as four more, mostly guitar, tracks to each song.

When we were done, we gave the final recordings to Mike Duncan, who’s a master mixer. He seamlessly blended everything together so it all sounds like it was recorded at the same time. He did a great job and I’m really happy with the outcome.

In terms of how Tony and I worked together, let’s use “Sordid Thing Called Love” as an example. Tony came up to the studio for an afternoon, invented a cool part, recorded a number of takes and then I edited them and added his contribution into the track.

Duggan-Smith: Neil and I have played together for so long that we intuitively understand where the spaces are for each other. We’re very different guitar players. I come from the acoustic side, and Neil is an amazing electric guitarist. So, we had this way of creating segments in the songs that were perfect for the other person.

What are your thoughts about how some of the more topical songs remain accurate today, such as “The Man in the Iron Glove,” “Keeping Warm in the Cold War,” and “Goldmine in the Sky?”

Duggan-Smith: It’s true—all of them sound like they could be about right now.

Chapman: I don’t throw the word genius around a lot, but in my mind, Graeme was a genius lyricist. He was able to capture thoughts about people and this world that are still contemporary and ring true today. It was one of the beautiful parts of doing the album—listening to the songs and understanding how they remain relevant. Graeme was unbelievably talented.

Duggan-Smith: With Graeme, it was never about him in his songs. A lot of people who perform these days are ego-driven. They put the focus on “me, me, me.” Not with Graeme. He was a storyteller. When you listen to his songs, you’re not thinking about him, his hair, what food he likes, or whatever. He’s invisible. His songs and everything we did were about serving the story.

I think Graeme’s songwriting approach is one of the reasons we all gravitated towards each other. We all knew his songs were so unique and about communicating important ideas. They weren’t about trying to get your face on a cereal box.

Pukka Orchestra album art also speaks to that. Our faces aren’t on them. They’re hidden. You might see them on the back cover or insert.

Describe Iris Williamson’s involvement in and support for Graeme’s solo album and the new Pukka Orchestra release.

Chapman: She was as close to Graeme as anyone ever could be. She’s a wonderful woman from Glasgow. Iris and both of us have a desire to keep creating a presence for Graeme’s talent.

When we were working on Graeme’s solo album, she had ideas she contributed. She was a great sounding board. If we wondered what Graeme would think about something, we’d ask her.

Iris was always very supportive. We all shared the same vision. She’s the executive producer for Chaos Is Come Again and Because You Were There. And whenever money was needed for the projects, she always provided it.

Iris and Graeme Williamson, 1984 | Photo: Iris Williamson collection

Iris and Graeme Williamson, 1984 | Photo: Iris Williamson collection

What do you think Graeme would have thought of Chaos Is Come Again?

Duggan-Smith: I think he would love it. He wrote these songs to be heard. And because he was so ill, he didn’t have the luxury of going out there and making that happen during the latter part of his life. He wasn't living in a vacuum, but because of his health, he had to be protected all the time.

Chapman: Graeme was a reluctant performing artist and although he was a really dynamic performer, he really didn’t enjoy that aspect very much at all. He just wanted to get his songs out there. Everything we did on this album was done in the spirit of what he would have wanted.

Duggan-Smith: It’s important to emphasize that we kept going over to visit Graeme in Scotland while he was ill to have songwriting sessions and hang out. Our friendship always remained. We were like brothers.

The Chaos Is Come Again album cover revisits The Palace of Memory artwork and combines it with some of the Dear Harry visual elements. Discuss how that came together.

Duggan-Smith: Back in the day, I came from a fine arts background. I spent years studying in England, and then moved to Halifax before relocating to Toronto. After attending school in Halifax, I felt it was time to reevaluate what I wanted to do with my life.

Bizarrely, Bruce Cockburn was playing in Halifax one night. I ended up meeting him and he offered to give me a ride to Toronto, so I could start a new life there. And that’s how everything fell into place.

Once I got to Toronto, I walked into a guitar shop and Neil’s there. We start talking and he tells me about Graeme. Neil also found me a place to live and then we started writing songs together, and things went from there. It’s incredible how the three of us fell into place back in the early ‘70s.

Chapman: Tony came to Toronto from art school in Halifax like a windstorm. I still remember his acoustic guitar having an incredibly intricate inlay, and this was before he became a luthier. He was already inlaying guitars and he introduced this talent into the growing Toronto luthier scene, which to this day includes some of the best luthiers in the world, including Linda Manzer, Grit Laskin, and David Wren.

Like Tony said earlier, we’re completely different guitar players. He’s an unbelievable fingerpicker, with his own unique style. He has an ear for melody and intricate chords. Whereas I’m the three-chord guy. Maybe five chords at this point. [laughs] But he would work on these unbelievably involved harmonies on his guitar and I’d just sit there in awe watching him play.

So, that’s how things started. And part of that was also Tony being the art guy for Pukka Orchestra. We would have these fantastic posters for the gigs that Tony created. They helped create a look and interest in what we did.

Duggan-Smith: The material on Chaos Is Come Again is originally from The Palace of Memory and Dear Harry sessions, so part of the overall concept was revisiting the artwork, as well as the music. We wanted to somehow marry those two albums together. It’s a little nod to the origins of the music, but also reflects that it has been revisited and updated.

We added the pink that we used on the debut album to it as well. That was my son Lucas’ idea. So, it has a reference to Barbara Klunder’s debut LP artwork as well. It has her original logo on it too, which she graciously allowed us to use.

Let’s go back to the first Pukka Orchestra single “Rubber Girl” from 1981, which you put out independently. Tell me about making it and getting it out to the world.

Duggan-Smith: We recorded “Rubber Girl” and its b-side “Do The Slither” across the road from where I was living in Toronto at a small studio called Captain Audio. The players were Graeme on piano and vocals, me on acoustic, Neil on electric guitar, Todd Booth on accordion, Larry Brown on bass, and Michelle Josef on drums. It was engineered by Jim Bungard.

A lot of our early songs came from parties during which we’d stay up all night playing guitar. “Rubber Girl” came from one of those. It was the last song we were working on one night as we were all falling asleep. Graeme stayed up and finished writing it. And when it was done, we thought, “Oh my God, we have a great song here.” So, we went across the road and recorded it.

We also had to come up with a name for the band. It came from a letter my grandfather sent me. He was British and was the harbormaster of Calcutta in India. When I told him I was playing in a group, he said “That’s very nice, but don’t bother with any mediocre bands. Make sure you get into a pukka orchestra.” In Hindi, “pukka” means first-class and genuine. We looked at each other and thought “it’s the perfect name for the band.”

Then we had to deal with the rigamarole of pressing singles and taking them to radio stations. But that’s when things started to happen. We got some Toronto stations and DJs to play it, including CFNY’s David Marsden and Q107. But it wasn’t a song everyone understood. Some people thought we were objectifying women in some way, but it’s actually a very sad song about a sad individual.

Pukka Orchestra, 1986 | Photo: A Major Label

Pukka Orchestra, 1986 | Photo: A Major Label

How did that lead to the Solid Gold deal and the self-titled debut album?

Chapman: The success of “Rubber Girl” created some important opportunities. Things began with Norm Corbett. He was an old friend of mine who I had a band with back in the early ‘70s called Cloud. He had opened up a studio in a warehouse area in Scarborough called Enormous Sound. It had incredible recording gear including a vintage Neve desk and Studer 24-track tape machine.

Norm introduced us to the artist manager William Tenn who also went by the nickname Skinny. He heard what we were doing and really thought it had potential. Norm was a larger-than-life guy who liked smoking lots of dope and having a great time. So, I took Tony and Graeme up to meet Norm at his apartment in Scarborough and he’s passing joints around the table. Tony and Graeme hardly ever did that sort of thing—if at all. We thought we should be polite, so we each had a toke and gave it back to Norm. Then he says “Oh no, man. I can’t smoke that shit. It’s way too strong for me.” [laughs]

Anyway, the meeting went well. Norm took us on and we recorded most of the album at Universal Sound Studio in North Toronto with Peter Willis at the desk. Norm and Bill funded the whole thing.

“Rubber Girl” was done at Captain Audio, and “Spies of the Heart” and “Wonderful Time To Be Young,” were recorded at Inception Sound. The latter two were produced and engineered with Danny Greenspoon.

Duggan-Smith: The tracks were almost finished and that’s when Solid Gold heard them. Skinny introduced us to Frank Davies, who was president of ATV Music at the time, before Michael Jackson bought the company and our publishing. He thought we were pretty good and sought out a record deal with Solid Gold for us. We used 70 percent of the original recordings on it.

Chapman: The only thing we didn’t have that they wanted was a single. Frank suggested the song “Listen to the Radio.” written by Tom Robinson and Peter Gabriel. Graeme, of course, wrote his own songs and was adamant at first about not doing it. But it was a very cool song and eventually everyone was convinced. We recorded that single at Eastern Sound studios, where it was produced by Gene Martynec. It was the only thing Solid Gold was involved in creating.

In retrospect, Solid Gold knew what it was doing in regards to breaking an artist. Their team understood what could be popular and they were right. So, we transformed the song, sped it up, added our guitar parts to it, had Jorn Andersen on drums and Howard Ayee on bass, and they released it as the first single. We were kicking and screaming as we did it, but it turned out to be a big success.

“Might As Well Be on Mars” was one of the first songs you all collaborated on. Describe how it came together.

Chapman: When we first got together in the early days, Graeme had already written “Might As Well Be on Mars.” We didn’t know Graeme that well yet and didn’t realize he had a unique way of hearing things.

So, Graeme plays us the song and we didn’t yet know he could get pretty dark sometimes when talking about his work and its meaning. Tony and I go full-on with Beach Boys-style harmonies as we sing the chorus. But Graeme got progressively darker and darker. We just thought it would be a great song for lush harmonies. Suddenly, Graeme put his guitar down and walked out of the room.

Tony and I were left sitting there going, “What happened?” It turns out Graeme couldn’t deal with the sweet vocal harmonies. That’s when we learned how precious his songs were to him—and they became equally as precious to us.

Duggan-Smith: Everything happened spontaneously between the three of us. It was always an organic exchange of ideas. I might go, “Here’s something I think works for the bridge” or ‘Here’s something I’m feeling for the chorus.” There wasn’t a big ego thing like in other bands. When it came to Pukka Orchestra, we were all looking for the best parts for the songs.

Chapman: The vast majority of Pukka Orchestra’s output started with Graeme’s songs. He’d first play it for us, and then Tony and I would contribute instrumental bits, bridges, arrangements, and solos. That was the case for “Might As Well Be on Mars.” Graeme was always the catalyst for the most part.

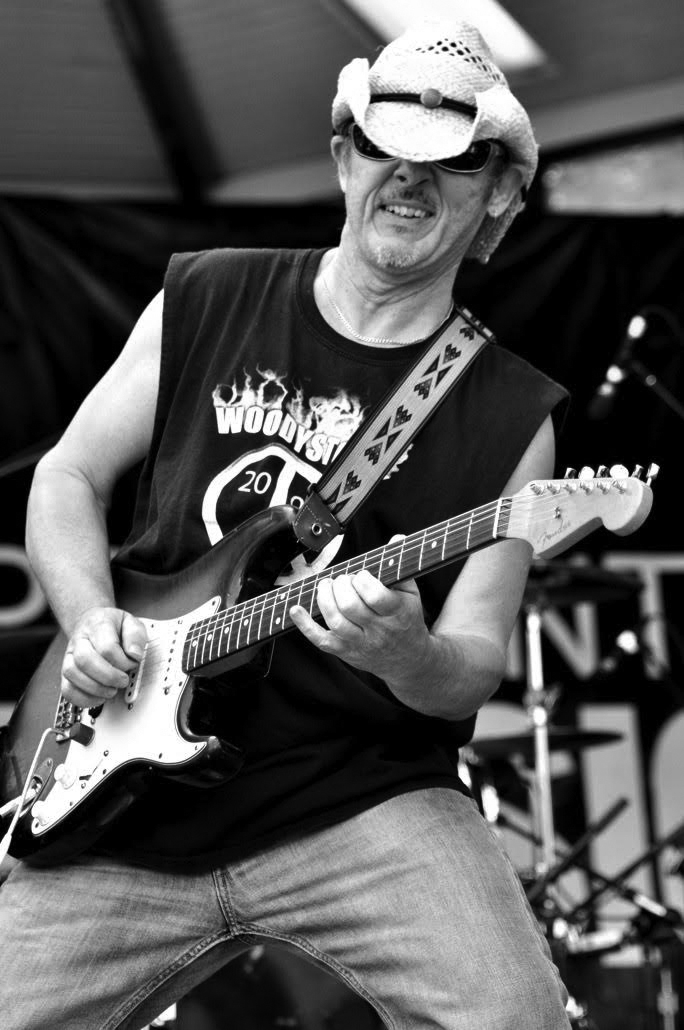

Tony Duggan-Smith, 2024 | Photo: Tony Duggan-Smith collection

Tony Duggan-Smith, 2024 | Photo: Tony Duggan-Smith collection

“Cherry Beach Express” explored police brutality in Toronto. It was an impressive and unlikely song for the era. Fast forward a decade and that topic matter became the realm of countless hip-hop artists. Tell me about the drive to write it and the aftermath of its release.

Chapman: Yvonne MacKenzie, Graeme’s partner at the time, came up with the title for the song. She worked in the Toronto probation system. Graeme was a great storyteller and a champion of justice. He was all about fighting for the underdog and doing what’s right. Tony also contributed to the writing of the music.

The 52nd Division in Toronto was infamous for taking people down to Cherry Beach and hurting them. Outrageous police brutality occurred there. Yvonne knew exactly what was going on.

One of the memories I have about that song is when I was driving to Grossman’s Tavern one night to play a gig. I had a Pukka Orchestra bumper sticker on my car, and I got pulled over by the cops. The cop said “Pukka Orchestra? We know what that’s about.” I responded, “Well, I’m in the band.” The cop grunted and walked away. Anything could have happened. Thankfully nothing did but they were not happy about it. They let me go, but the fact is I was stopped by the police because of that song.

Duggan-Smith: The song caused a lot of controversy with the police, but the legend says they attempted to ban the song from radio, and that’s not true. I think that was the publicity people at the label trying to stir the pot. What is true is that the police went to Sam the Record Man, one of the big record chains in Canada, and tried to get them to remove our albums.

It was an odd thing, because the song is actually very upbeat, even though the content and story are kind of dark. It has a big, rousing chorus. But like you said, it’s dealing with the same subject matter as a hip-hop artist talking about police brutality. That was also one of Graeme’s songwriting delivery system tricks—making listeners think a song is about one thing but then it becomes about something else.

Chapman: Eventually, the police left us alone because they knew if they were pressed on the Cherry Beach stuff that they would have to admit it was true.

Reflect on the making of “Spies of the Heart” and its unique arrangement.

Chapman: For me that is the definitive Pukka Orchestra song. We wrote it all together. It started with a little Casio keyboard part I had, and then Tony added to it, and Graeme wrote lyrics for it that were perfect. It’s a magical song, with lines like ”This isn’t Mi5.”

Duggan-Smith: It’s so simple. It’s not a rock song. It had elements of humor and darkness.

Chapman: I think it was the very first song we all wrote together.

Duggan-Smith: That’s right. We didn’t originally write it to a lyric. We worked on the music and then it evolved into a song.

Chapman: At one point, I was going to do the lead vocals and I’m glad I didn’t. But that’s kind of how I tend to sing—with a spoken word approach. I gave it a go, but brighter heads prevailed, and Graeme ended up singing, or rather reciting it.

Solid Gold rapidly tanked after you released the album. Discuss what happened and how it affected you.

Chapman: Solid Gold did a lot of good things for us but they tried to change our record deal for the worse in mid-stream and things got ugly. Because we wouldn’t accept the contract changes, they didn’t release the album in the States. Soon after, they filed for bankruptcy.

Duggan-Smith: The worst part was we later found out all our master tapes had been seized by the bank, and then had been destroyed in a flood in a basement at its main branch.

We could have pursued legal recourse, but Frank Davies, who still works with us and is playing a major role in getting Chaos Is Come Again and Because You Were There into the world, had a life-changing conversation with us. He said “Tony, Neil, and Graeme, let me paint a picture of the future for you. It’s 30 years down the road. You’re on your seventeenth court case trying to get some satisfaction from Solid Gold. You’re angry, bitter, sour old men. Is that what you want for your future? My suggestion is look back on those days with Pukka Orchestra as a lovely time and move on.” I thought the situation was very unfair, but realized he was telling the truth. Thanks Frank.

Chapman: Thankfully, we were happy with how the album came out. Not having access to the master tapes meant we wouldn’t be able to revisit them or rework them. In some ways, it’s good we don’t have that temptation.

Duggan-Smith: At the same time as the bankruptcy of Solid Gold, Graeme had gone to Scotland and collapsed with kidney failure. We had also won a CASBY award from CFNY for best up-and-coming band. It was a strange time. There were lots of signs that things were changing. It was time to face reality.

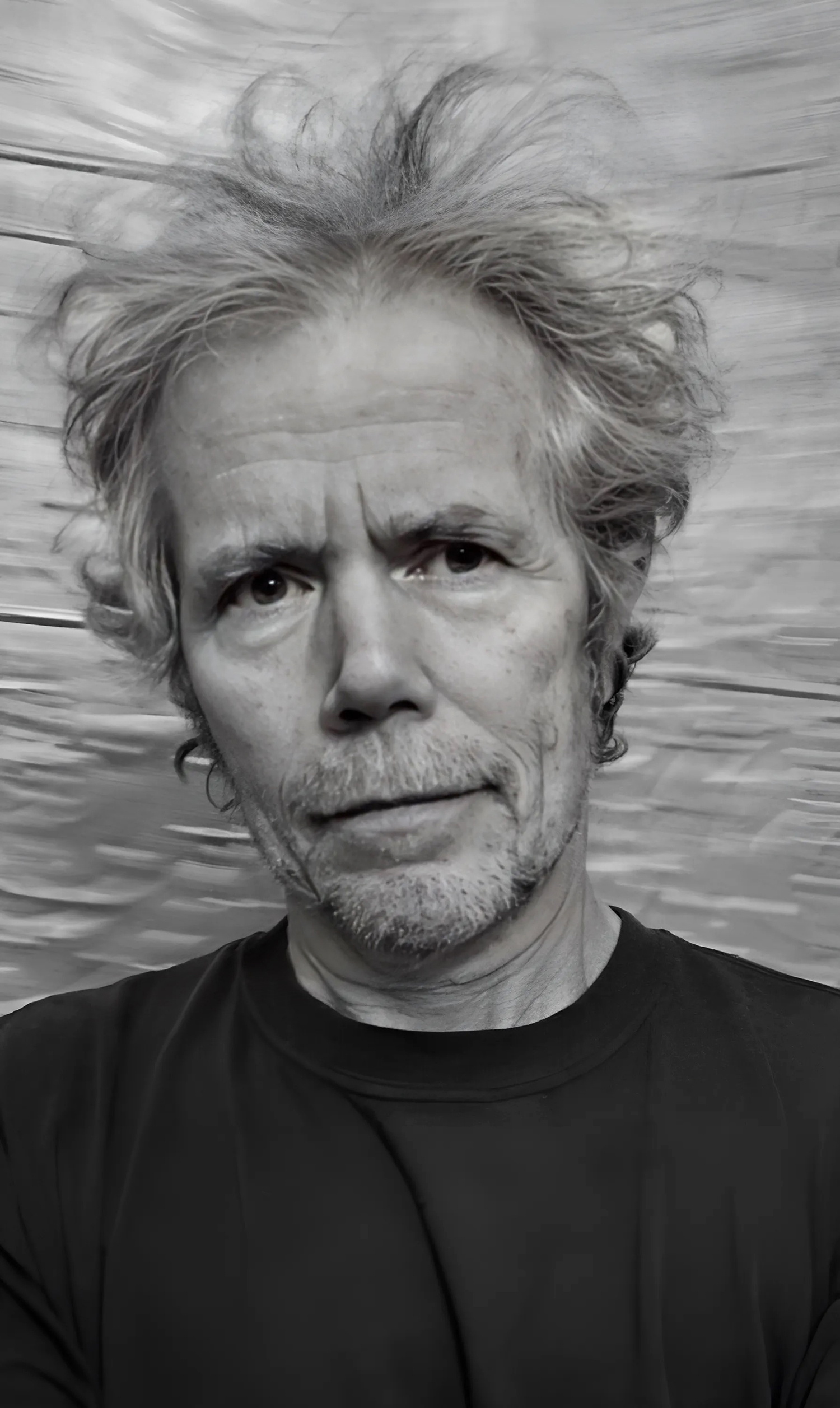

Neil Chapman, 2024 | Photo: Neil Chapman collection

Neil Chapman, 2024 | Photo: Neil Chapman collection

Pukka Orchestra live was more of an ecosystem than a band. Talk about the extended lineup that comprised the gigging version of the group.

Chapman: The joke was “Are you in the Pukka Orchestra? Why not? Everyone else is.” [laughs] We had so many friends in that incredible Queen Street scene in Toronto.

The core of the band was Tony, Graeme, and myself. On bass, we had Randall Kemph, Steve Webster, Shane Adams, or Howard Ayee. On trumpet and background vocals, we had Denis Akiyama, my best friend in high school. Gordon Phillips, our percussionist, was Graeme’s old friend from the North of England. And just like in This Is Spinal Tap, our drummers would come and go up in a puff of green smoke. They included Michele Josef, David Norris, Jorn Andersen, Randall Coryell, and Ben Cleveland. The same was true with keyboard players. We had Todd Booth, David McMorrow, Gary Breit, John Whynot, and Mary Hanson over the years.

So, there were a lot of people in the band. Sometimes we’d play places like Grossman’s Tavern, The Horseshoe, or The Bamboo in Toronto, and somebody we know like Trudy Artman or Jane Siberry would walk in. Suddenly, they’d be singing background vocals on stage. It was an organic experience not unlike a herd of elephants rounding the bend.

Tell me about the second Graeme posthumous solo album that will eventually see the light of day.

Chapman: Graeme had more than 30 songs that he’d written but not properly recorded. We used 15 of them on Because You Were There and there are a lot more. We’re discussing the next album as we speak. We have the songs and they’re really great. Graeme rarely wrote a song that wasn’t world class. So, once the cycle for this Pukka Orchestra album is done, Iris, Frank, and I are going to discuss how to realize the next one.

Describe what both of you focused on after Pukka Orchestra ended, and your most recent activities.

Duggan-Smith: Before the end of Pukka Orchestra, I apprenticed as a guitar maker. I put fine art behind me and went forward with the guitar thing. I got into building my own guitars. I do a lot of work with Linda Manzer. Right now, I’m finishing working on one of Lenny Breau’s guitars for his family. It had been left to the family in a will from a musician who got it after Lenny died in 1984. They’re working on a documentary on Lenny, so they had me fix up the guitar for this project.

I also work on apprehension engines for film and video game companies. They’re hybrid instruments that are sort of part guitar, percussion instrument, and sound effects. They’re used in soundtracks. I’m a very happy-go-lucky guy, but I’m working on creating one of the most miserable, haunting, scary instruments on the planet. [laughs]

In addition, I worked as a set designer for a decade in films mostly for American companies. I had no experience doing that, but a person who helped us make the Pukka Orchestra videos explained how I could get a top job at a film company in the set department without any experience. I had nothing to lose. I walked into a major film company and walked out with a job, which totally blew my mind. It all worked out.

Beyond all of that, Neil and I had two bands together: Autocondo and Neotone. Both of them made albums and we even had a record deal with Touch Wood Records out of New York. Graeme made an appearance on the 1996 Neotone album called O-My.

Chapman: After Pukka Orchestra I carried on playing music, which is what I’ve done my whole life since high school. I did a lot of studio session work. I was one of the main guys in Toronto people would call when they needed a “rock guy” on guitar. I did a lot of sessions and live gigs with artists like Carol Pope, Rough Trade, Alannah Myles, Rita McNeil, The Boomers, Dan Hill, Buffy Sainte-Marie, Leonard Cohen, Robert Priest, The Sattalites, and Leroy Sibbles, among others. I also co-write soundtracks for movies and documentaries with Bruce Fowler or Russ Walker. Bruce and I are nominated for a Canadian Screen Award for best original music in a documentary for our work on Bug Sex (It’s Complicated).

Another main focus is the band Zed Head with my buddies John “The Fogman” Burkitt, Smilin’ Bob Adams, and Bruce Morrison. It’s a very exciting group that does original Canadian-style Southern Rock. We have a new album called Shiny Things, and just got back from a tour of Sweden.

I’ve also released three solo albums: Hollywood World, Hope in Hell, and Gitar, which is an all-original instrumental electric guitar album. In addition, I put out a funky instrumental EP called Happy Everything, which is my idea of what Christmas songs should sound like.

Mainly, I raised a family. I have two kids now in their twenties: Carter and Tiana. As I like to say, “They’re growing up and I’m growing down. [laughs]

It’s a good life. I’ve been blessed with having great friends and being able to make a living by doing what I love to do which is playing guitar, singing, and writing music. I’m thankful everyday that I’m able to get up in the morning and do those things.