Donate to Innerviews

Since 1994, Innerviews has provided uncompromising, in-depth interviews with musicians across every genre imaginable. And it does that with no trackers, cookies, clickbait, or advertising.

Your donations are welcome to help continue its mission of highlighting incredible music and artists, without any commercial considerations.

Your contributions will be instantly transformed into stories and videos, and cover hosting and web management costs. Importantly, your dollars will help ensure Innerviews remains absolutely free to all visitors, independent of their ability to financially support it.

Please consider making a donation today by using the PayPal QR code below.

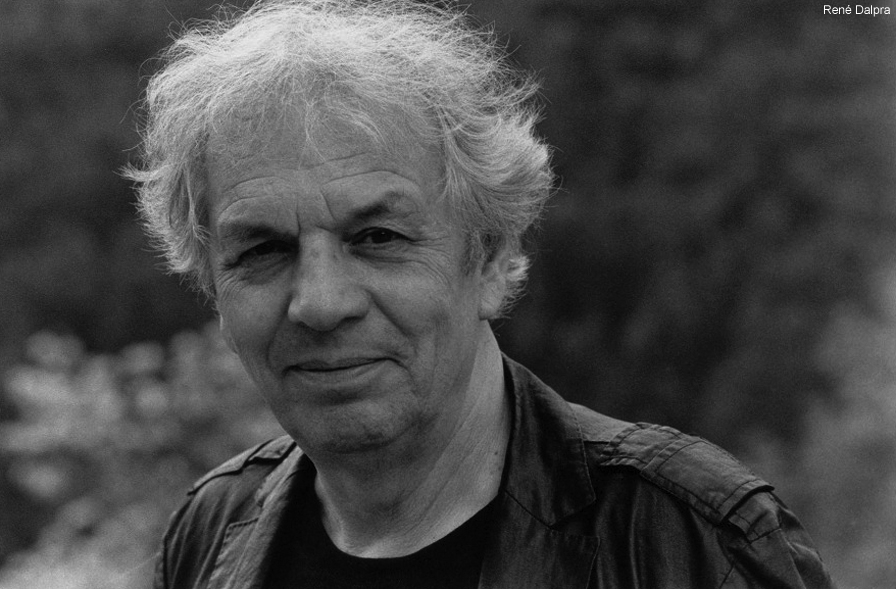

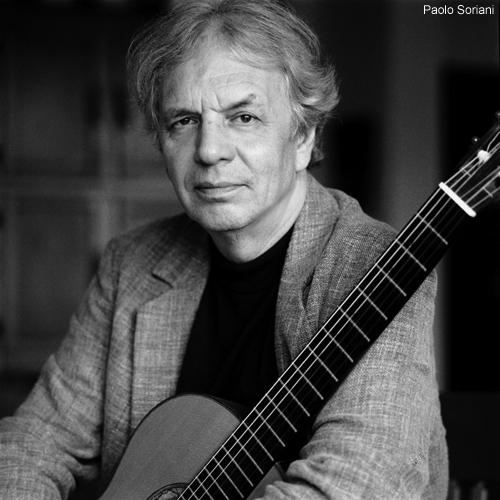

Ralph Towner

Magic and Affirmation

by Anil Prasad

Copyright © 2017 Anil Prasad.

Ralph Towner believes music is something that wills itself into existence. He applies that perspective to his compositional approach that has yielded hundreds of pieces across his solo career and as a member of Oregon.

Towner recently released My Foolish Heart, a solo guitar album named after the standard of the same name, originally written by Victor Young and Ned Washington. Pianist Bill Evans’ renowned interpretation with his trio featuring bassist Scott LaFaro and drummer Paul Motian played a pivotal role in propelling Towner’s creative instincts in the early ‘60s, first as a pianist, and soon after, as a virtuoso acoustic guitarist. Towner’s highly-sensitive and contemplative interpretation of “My Foolish Heart” reflects the beginnings of his journey. The album’s other 11 originals illustrate his ongoing evolution and drive as one of the jazz world’s most important writers.

That evolution includes revisiting previous work to uncover additional possibilities. The album features solo interpretations of two pieces by Oregon—“Rewind” from 1995's Beyond Words and “Shard” from the group's debut recording, 1972’s Music of Another Present Era.

Oregon has quietly, yet profoundly influenced the trajectory of Western music since forming in 1970. Towner, reedman Paul McCandless, bassist Glen Moore, and the late percussionist and sitarist Collin Walcott created the group after previously working together in the Paul Winter Consort. Oregon combines jazz, classical, folk, Indian, and Latin elements—just to name a few—into its inimitable sound. It also blends intricate compositions with improvisation across its 28 albums and live performances. Oregon was one of the first groups to pursue a musically borderless vision, inspiring countless jazz, jazz-rock and world fusion groups to do the same.

Oregon just released Lantern, a highlight of its latter-period output. The title track is an entirely improvised, dynamic piece which begins with intricate counterpoint and minimalist elements before evolving into animated rock-inspired territory. The album offers six Towner compositions, as well as one track written by each of the other current band members, including McCandless, drummer Mark Walker, and bassist Paolino Dalla Porta, who joined the group in 2015. Lantern encompasses all of Oregon’s hallmarks, such as lyrical melodies, lilting and propulsive rhythms and sophisticated group interplay.

“Ralph wrote some beautiful music for Lantern,” said McCandless. “Most Oregon records live and die by Ralph’s pen. Ralph is a rarity in that he’s a great guitarist, improviser and performer, while also being such an impressive composer. That’s his greatest gift. What Ralph writes for me to play in Oregon is right up my alley. I always feel I know where to go with his music. Like Duke Ellington, Ralph can put a musician’s name on the part.”

At 77, you’re more prolific than most musicians a third your age. What informs your intense drive as a composer?

It’s related to wanting to complete an idea. I basically write by playing. If I discover something as I’m practicing on the instrument, I’ll want to pursue it further. I’ll discover the first few elements of it and then telescope it into a whole piece. I’m curious to see how the stories turn out. Writing is like reading for me. Similar to when I start a book, if the material reaches out and grabs me, I’m pulled along just like a reader is, wondering where the piece is going to go. In that way, I’m almost a member of the audience seeing how the piece will unfold. I’ve always been quite driven in the solo element. I’ve always wanted to ensure my work, particularly on the classical guitar, holds together and is fully realized.

Contrast what it's like composing for your solo albums versus writing for Oregon.

I have to be able to play the piece solo on guitar for it to be on my own albums. I can’t do that with every piece to the extent I want to. I’m always trying to emulate other instruments and combinations of instruments on the classical guitar. I’m also always interested in finding different harmonies that are unique to the guitar. Those things are considerably more difficult than writing pieces for Oregon. When I write for Oregon, things are a lot easier because I’m going to be an accompanist. My role isn’t to play every aspect of the music. I’m not responsible for playing the entire melody. I can write difficult jazz pieces knowing what the capabilities are of members in the band.

Tell me why the composition “My Foolish Heart” has so much meaning for you.

I was completely bowled over by the piece when I first heard it at a music professor’s house in 1962. He was quite a good piano player who played very much like Oscar Peterson. He would always play me his Peterson records. I would say “Those are very nice.” And then one day, he played me Bill Evans’ Waltz for Debby and I heard “My Foolish Heart.” It blew me away to the point where I decided to really pursue the piano. Until that point, I sort of dabbled on the instrument. I was previously doing all of my improvising on horns during elementary and high school.

“My Foolish Heart” is a masterpiece. It’s a ballad, but it’s so powerful. It reflects a whole lexicon of harmony, voicing and voice movement. The way Scott LaFaro would alter the bass notes of the chords was also incredible. It didn’t have a standard jazz time feeling. They were working in what they called “broken time.” LaFaro’s bass playing and the sense of space each musician had in Evans’ trio also hit me in a way that was completely mesmerizing and emotional. I wanted to know what it felt like to be in that sphere and play music that way. So, I started to clone Evans’ piano style.

I was already working with Glen Moore at the time, who had a great bass sound. It was actually very LaFaro-like and we started to refine that further. At the time, I also had a wonderful roommate named Jack Murphy who was also a bass player and knew his harmony quite well. He was at least 10 years older than me and we shared a small apartment for years in Eugene, Oregon at college. He was an excellent bassist and played mostly in dance bands. He was a great help as I slowly developed as a piano player.

Later in 1962, I bumped into the classical guitar when I was graduating from the University of Oregon. I realized at age 22 that it was something I really wanted to learn. I tried to teach myself and realized that it wasn’t something that was easy to play. The notes don’t just sit there waiting for you to press on them with your fingers. I managed to find this great maestro in Vienna named Karl Scheit and went over there to study with him. All I did was play there in this tiny little room, with snow blowing in the window. I was eating next to nothing. I practiced up to 10 hours a day, seven days a week for nine months straight. I found at the end of that, I could actually play classical concerts. It became a complete obsession. I think that also goes back to your question about drive. There was more drive in learning the instrument than anything I’ve done. Something told me I had to really do something that severe in order to play the instrument the way I wanted to. I guess I have that drive in my nature.

I understand “My Foolish Heart” has another interpretation for you that emerged in January 2015.

What happened is I came to a crashing halt at the Hommage à Eberhard Weber concert held at Stuttgart’s Theaterhaus that month. Many of us were there to celebrate Eberhard’s 75th birthday. He had a stroke many years ago and can’t play anymore. So we wanted to do this wonderful show for him. Paul McCandless, Pat Metheny, Gary Burton, Scott Colley, Danny Gottlieb, and the SWR Big Band were there. It was a nice collection of people Eberhard had worked with and loved. I managed to make it through the first day of rehearsals and everything went well. All of these arrangements had been done with the big band and I was set for the two concerts. During sound check of the night of the first concert, I literally blacked out. I felt overheated on stage, I bent over to plug something in, and the next thing I knew, Gary Burton was putting me back on a chair. I fell face first into the music stand. Someone grabbed me at arm’s length before the guitar was smashed.

I went to the hospital in an ambulance and learned that my heart had slowed down. It stopped, basically. So, I wasn’t able to play either concert. It was the weekend and there weren’t any surgeons on hand. I spent a day-and-a-half at the hospital and checked out to go back to Rome, where I live. They suggested I get a pacemaker. They said if I didn’t, I might not wake up one day. My foolish heart was only beating 40 beats a minute without it.

How are you doing today?

It’s amazing how much better I am. Getting a pacemaker isn’t a complicated procedure. Almost everyone has one at my age. I recommend people getting them in different colors to be fashionable. [laughs] All it is, is a small battery run by a computer that’s tucked under your skin. They don’t even cut muscle anymore. The pacemaker sends two wires down into your ventricles of your heart. It gives your heart a pulse via the path from your brain to your heart. That was blocked previously and was arrhythmic. My heart always beat very slowly, but this time, it went too far. I was too far gone. Now, it’s set. The procedure was only an hour. Two days later, I did a radio program in Switzerland. I had to take it a little slow, but I was already functional. Today, my heartbeat never falls below 60. Immediately after surgery, my skin color and facial color changed to something a little more red and less green than it had been before. My circulation is better. I felt more energy almost immediately. It’s a great thing.

We’re losing so many incredible musicians lately. How has that affected you?

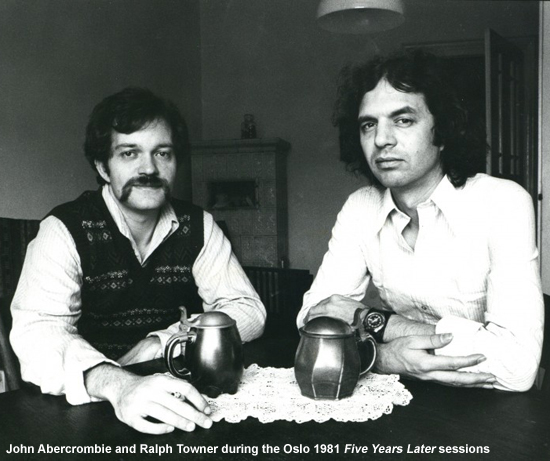

We’re getting old, that’s for sure. People are starting to go from my peer group. We’ve lost John Abercrombie, Paul Bley, Allan Holdsworth, John Taylor, and Kenny Wheeler, just to name a few.

When I think of John Abercrombie, I have a flood of joyous memories of the years we spent touring, playing and just hanging out. We lived two cross-town blocks away from each other in the 2000s. When we weren’t touring, we would still spend time together. He brought so much joy to everyone who heard him or met him, and that’s what remains indelibly.

Allan Holdsworth was someone I really admired. We did a little interview thing together in Baltimore once at a guitar festival. Allan was really interested in what I did and genuinely excited. We never really got to sit down to explain to each other what it is we do in detail, though. The day I read about his death in the New York Times, I went to YouTube and found a few interviews with him and lessons he gave. I loved Allan’s approach. We also had a similar sense of humor, too. He was a person I would have really liked to have spent more time with.

My Foolish Heart has a piece titled “Blue as in Bley.” Tell me about its construction.

From the very first melodic line, the piece was set up as a blues thing with both a major and minor third in it. So, it has a nice, biting sound. It sets the theme and then the melody makes its entrance. The melody is the protagonist of the play. First, I have to have the scenery. So, that’s the initial blues bit. Next, I wanted to have a very angular melody to suit the short intro between the two chords. I heard it as sounding abstract, but still with a blues form, loosely. There’s no set meter. There’s a pulse to the piece, with some bar lines that ended up being in 7, 7/4 and 4/4. There are a lot of meter changes, but it still keeps the same tempo. This one is very much an improvised piece. I felt the mood described Paul Bley very well. He was an old friend of mine. He was a great storyteller. His compositional approach and playing had that angular, spare quality to it. I felt it would be a nice thing to salute him by calling it “Blue as in Bley.”

“Ubi Sunt” from the new album has a melancholic feel to it. Tell me what it communicates.

I was having a conversation about “Ubi Sunt” with one of my best friends, the drummer Horacee Arnold. We Skype a lot. I looked up the root of this word and it’s a Latin term meaning a remembrance of things past or events that have already happened. It’s a tune that grew from the first few notes I played and I followed it to create the rest of the piece. I initially wrote a few events, including intervals and the first two chords, and they generated the rest of the piece from there. It wrote itself after those. The piece went in the direction it had to go. I didn’t dictate the time signature or anything. It came out as a little classical piece. It felt complete without any improvisation in it. It also felt like a small story about something that had already passed, so I used that name.

It sounds like your creative process is about pure intuition with conceptual elements applied at the end.

It’s not a case of me seeing a tree and being inspired to write something about trees. For me, music has its own way forward and its own language. Music has a whole world of meaning in and of itself without being attached to anything verbal. Once a piece is in finished form, that’s when it needs a name so you can refer to it. I try to pick titles that make the listener want to hear the piece. It usually always comes later. I do think titles and concepts are very important, but they come after the fact, once I’ve listened to a piece in finished form and determined how it affects me.

I get into trouble and make a lot of mistakes if I’m performing and some kind of verbal thought enters my mind. The speed of verbal language is so slow and unwieldy compared to music. If I even have a thought like “Oh, that was beautiful” while I’m playing, I’ll immediately lose my place and my whole musical train of thought. When I’m playing, I’m making decisions so fast and it’s not about words. The tones, harmony and meter are changing so quickly. I’m conjuring these things up as I play. That holds true even if I’m reading music. When I’m improvising, I also have to be totally focused. Any sort of judgmental thoughts like “I hope people like this,” “This feels good” or “I’m feeling awful” pulls me away from the speed I have to maintain to improvise really well. So, I try not to be distracted and pulled into the verbal world when I’m playing. I feel quite strong about this.

Lantern, the new Oregon album, is an exceptionally strong effort. What defines this recording for you?

For this one, we wanted to have everyone contribute to the writing and that serves it well. It’s still jam-packed with my stuff as the most prolific composer, but it was still nice to take this approach. It’s the first recording with Paolino Dalla Porta on bass. He brings a whole different way of playing to the group. He’s a real virtuoso and very easy to play with. He has a great musical background, like all of us. He has a lot of experience with classical music and jazz. He’s a tremendous jazz musician. He’s also a wonderful ensemble player. Paolino has been with us for three years now in this new formation and it doesn’t sound like the usual Oregon stuff. You’ll also hear Paul playing oboe on this album.

Everyone is so dedicated to playing the music. There isn’t a blasé bone in anyone’s body. It’s a wonderful thing to have that in a group. We’ve played together for so long, but there’s still this great enthusiasm for the music. I don’t think we’d continue if that wasn’t the case. With Paolino, we have a great blend of musical experiences that’s pooled together into our language. What an exceptional thing music is as a group activity. Everyone in the group contributes and helps determine the directions the music goes and how it feels.

The title track is a mercurial, improvised piece. Describe the approach that enables the group to create such sophisticated, nuanced free-form work.

It’s an excellent example of how well us four people work together. We’re known for our free-form pieces, in which we play without any repertory ideas or anything. We just launch and start composing together from the moment an initial sound comes out. Whatever happens, happens. These pieces pool all the knowledge and experiences we have in the worlds of 12-tone, serial music, atonal music, polka, Dixieland, bebop, Brazilian music, and Indian music. All of this music has had an effect on us. Everybody in the group has such broad knowledge of all kinds of different music. We can delve incredibly deep into different realms together. We play at least one piece like that during our concerts.

We’ve been doing these free-form pieces since the very beginning. In New York City, we used to play a lot at WBAI in the early ‘70s. It was an underground radio station housed in a church. We built our following from playing there from midnight until 6am non-stop, doing mostly free stuff. We got quite a reputation from that. They also had this thing called the Free Music Store, a weekly live performance series at their studio. It was a beautiful space.

I remember at one of those shows, Aaron Copland came to see us and loved it. He said “You guys are just doing this stuff, whereas Luciano Berio is writing like crazy. You guys can just improvise it.” He was blown away by us. That was a feather in our cap. I think he’s right in that we’re able to compose as the music Is created. If it’s really well played, it can be as good as a written piece. I think what makes it work is that people understand when to be more dominant or hold back and be less dominant. It isn’t an enforced democracy in which everybody has to behave and fulfil a role. Everyone is free to alter their role if they feel like breaking out. It’s four people composing at once.

Tell me about the process that occurs when an individual presents one of their own compositions to the group.

If it’s my piece, then it has a whole set up before we add any potential improvised development within its sections. When someone brings in a tune, we learn it and the rules that might be involved. There might be a harmonic scheme or melody that’s very identifiable that needs to be adhered to. So, the scene is pretty much set. The rest of us become interpreters, but we’re still improvising stylistically on the pieces.

Lantern features “Duende,” which you also recorded with Javier Girotto on his Aires Tango album, as well as with your trio with Wolfgang Muthspiel and Slava Grigoryan on the Travel Guide release. What makes it work in those different contexts?

It’s a piece that requires accompaniment. So, it was something that worked across these collaborations. It’s pretty much the same form in each case. It’s a piece that’s different from an A-B-A form. It’s more of an A-B-C-A thing. It’s quite sectional. It’s such a nice tune and it has some very tricky rhythms in it. It started with me singing the melody and evolved from there. The melody is really nice. I wrote everything at once after that. It’s not like “Here are the chords and now I have to figure out a melody.” The chordal patterns inferred the melodies. It happens in a way that’s exciting for me. I could write a lot of pieces that are musically correct, but they wouldn’t be very moving. I have to wait for an idea that’s really attractive to me. It really has to want to be written. That’s something “Duende” represents. The melodic trick is that the melody repeats, then breaks that repetition, which throws people off that want to play the melody in a symmetrical way. There’s an intentional asymmetry to it that somehow makes the whole thing come alive.

Oregon revisits “The Glide” on Lantern which it previously recorded on 1985’s Crossing and in 2005 as a 35th anniversary single. What made you want to re-record it?

The reason we re-recorded it is because Paolino joined the band. He’s a virtuoso in the Marc Johnson or George Mraz sense. He’s a masterful, graceful player with a great sense of rhythm. His bass playing on this version is astoundingly different. He plays beautiful, melodic solos that are logical and make you forget he’s playing such a difficult instrument.

Tell me about the guitars you used on My Foolish Heart and Lantern.

I had to record My Foolish Heart on a new guitar. My old faithful 1995 Elliott-Burton classical guitar was trashed coming back from Brazil after a solo concert. It somehow must have been dropped on the heel of the case from a great distance—probably on the tarmac from the hold of the airplane. I had taken it as a carry-on from Rome to Brazil, but they wouldn’t allow it on the way back. I had it in a hard case, but not my usual travel case. The first leg of the return trip involved a plane change in Sao Paulo from a Brazilian airline to Alitalia. So, there’s no telling which airline did it. All of my instruments are insured, fortunately.

My friend and instrument maker Giovanni Garafolo in Palermo reconstructed the guitar and I play it at all my concerts again. But it wasn’t quite ready when I was making the album, so I prepared it on a new guitar I like very much. It’s a guitar made by Jim Redgate. He makes a lot of great guitars for Slava Grigoryan. He also makes Pepe Romero’s guitars. It’s a wonderful instrument with a very quick response. It’s quite different from my other one, so I practiced more on it than I have in years to prepare for My Foolish Heart. I also played it a little differently. In a strange way, it had a good effect on the outcome.

On Lantern, I’m playing my Elliott-Burton, which really seems perfect in every aspect for me. It has East Indian rosewood and European spruce. It’s the most perfectly-balanced guitar I’ve ever played.

Oregon’s Elektra studio albums, 1978’s Out of the Woods and 1979’s Roots in the Sky, were just reissued. How do you look back at those recordings?

Well, no royalties were ever paid from those. I don’t even know who owns them anymore, but they are both wonderful records. I’m kind of blown away when I hear them. I’m astounded at how well we played on those records. Paul McCandless in particular just kills me when I hear them. Collin’s playing was so brilliant, too. Roots in the Sky was a real breakthrough in terms of the rhythmic cohesiveness of the band. It was a very confident-sounding record. Out of the Woods was the most popular album we ever did. It was just loaded with beauty. Collin’s playing has an incredible, painterly quality about it on the record. People loved “Yellow Bell” from that album. The albums were also marketed and distributed really well. Out of the Woods even got a Grammy nomination for the cover, but not the music. [laughs] It got a lot of attention. The nine Vanguard records did well, but this was on another level.

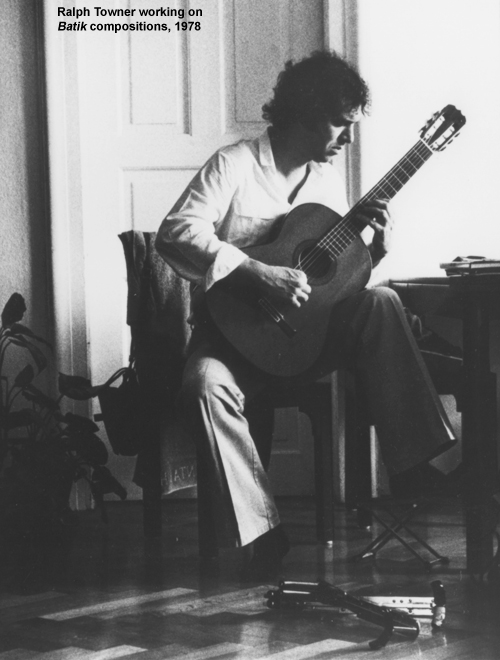

In 1978, you also recorded and released a solo album titled Batik on ECM. What are your thoughts on that disc?

Wow, that’s right—three records in two years. I must have been a real beaver, writing like crazy. I’m still writing a lot. But I really had to write a lot of music back then. There was no Internet at the time, so there wasn’t so much free music. People would record cassettes, but we still had vinyl records and they really sold well. There was an incentive to make and release a lot of music. I don’t think Batik was so momentous, but it had great players on it with Jack DeJohnette and Eddie Gomez. It was one of my lowest-selling, least popular solo albums. But maybe people picked up on it later.

Tell me the story of making Oregon’s Our First Record, the group’s first album in 1970, which didn’t come out until 1980.

Oh God, that was weird. Collin knew this hippie folk singer in Los Angeles. The singer was part of this completely laid back, stoned group of people. One of them was a rich guy with a strawberry farm empire. He had his own record company. Collin managed to get us some sort of record deal. We were still members of the Paul Winter Consort at the time. That’s when we branched off and got a chance to record. We knew we wanted to form our own group. They let us make an album as long as we would accompany the folk singer on their record. So, that’s what happened and that was the plan. We recorded the album in Los Angeles at their big, sprawling ranch house. It was very weird and very California.

The record company never managed to release the album and went under. In a way, that was good, because it gave us an album we could use to get out of our deal with Vanguard. They had us sewed up for years. So, we submitted that as our final Vanguard album and it came out 10 years later.

Elektra came along with some really large money for us when we signed with them in 1978. Record companies still had a lot of money that they wasted and blew like crazy back then. We managed to get quite an advance for Out of the Woods. We were at the height of our popularity.

Why did the group choose the name Oregon?

Initially, we kept coming up with stupid names for the group. At one point, we thought about calling ourselves Thyme. We also thought about naming ourselves Music, but someone else was using it. We chose Oregon because there was a venue in Woodstock that kept booking us. When we got there, we’d have a different name each time. One time, Paul McCandless arrived first and the club owner said “What are you calling yourselves this time?” Glen and I would always talk about how beautiful Oregon was. It felt so distant and fantasy-like. So, Paul said “We’re Oregon.” Twenty people we didn’t know showed up for the gig and remembered that as the band name. So, we became committed to using the name going forward.

Reflect on the creation of 1973’s Trios/Solos, your first ECM recording.

Around that time, Dave Holland and I played a concert that Manfred Eicher came to. We were doing Dave’s music. I played a little guitar and electric piano. Bob Moses was the drummer. Michael Brecker was there, too. Dave was a real powerhouse. He’s incredible. Dave introduced me to Manfred, who said he had started a record label called ECM. I somehow had the idea it was some sort of musicians’ co-op label. I misinterpreted what it was. So, when Oregon got an offer to sign to Vanguard, we took it.

Manfred then came up with an offer to do a kind of duo project. Glen wanted it to be a duo between me and him. But Manfred was kind of hoping we could use Paul McCandless and Collin Walcott on it, but not all at once. So we did that and Vanguard sued ECM over it. Vanguard collected all the money for the record, because it was basically a hidden Oregon album in a way.

That album was also memorable because on one studio day, I was asked to come in and record some solo playing, mostly 12-string guitar. So, I sat in there playing solos and staring through this big picture window where the control room was. Manfred and the engineer were in the control room, along with Keith Jarrett. He was right there in front, watching me make my first solo recording. He was checking me out to see if I would be usable for an upcoming string and guitar concerto piece he had written. I ended up recording that piece with him, titled “Short Piece for Guitar and Strings” on his 1974 In the Light album. Somehow, I didn’t feel any stress having Keith sitting in front of me.

So, our album was finished and came out as Trios/Solos and Glen was really upset. He thought we were going to make a duo record. But what Manfred really wanted a sneakily-made Oregon record.

How did you come to perform on Weather Report’s “The Moors” from its 1971 album I Sing the Body Electric?

It’s a wonderful story and a microcosm of what was going on in New York City then. Just to set the scene, I remember playing at a jam session at Randy Brecker’s apartment one night. I was on piano. Someone knocked on the door and in came this really well-dressed guy carrying an electric guitar and a little amp. He plugged it in and started playing wonderful stuff. It was John McLaughlin. He had just arrived from England and found himself in the same building and just wandered into our jam session and started playing on this tune of mine. That’s the way things worked. Word would get around among musicians that there was a new guy in town.

The Weather Report connection started prior to I Sing the Body Electric. During that period, everybody was playing with everybody else. I had an after-hours club gig on the Upper East Side. Glen Moore and I would sometimes do duos. One night I had a trio with me. It was Airto Moreira on drums and Miroslav Vitous on bass. Mirsolav then mentioned me to Wayne and he got curious about my 12-string thing. So, Wayne called me up. It was two years before I Sing the Body Electric. Weather Report wasn’t even organized at that point. We spent a whole afternoon playing each other’s music. I played some stuff I had done with the Paul Winter Consort. He was showing me all these great tunes he was writing for Lee Morgan. Wayne was fishing around for people for this group he wanted to put together, which became Weather Report. Of course, Joe Zawinul ended up putting his thumbprint on that group as well.

I didn’t join Weather Report, but two years after that meeting, Weather Report called me up and asked me to play on “The Moors” for their second album. Strangely, my 12-string guitar was stolen just before that. So, I had to rent one for 10 bucks from a music store in the Village. I didn’t even change the strings.

So, I showed up to the session and from Joe’s point of view, I was quite nervous. Wayne presented me with this unbelievably-difficult looking page of music. I had always tuned my 12-string down a step since working with Paul Winter. But when I saw Wayne’s music, I realized “Oh my God, I’ll have to transpose it.” Wayne said “That’s okay” and he went and rewrote the whole thing, transposed so I could read it.

So, I’m picking away and fumbling away on it. I started playing it and tried it a couple of different ways and realized it wasn’t working for the band. I said to Joe “Can I take a little time to work on this?” The band then left the room. Joe went back into the recording booth and said “Turn the fucking recording machine on.” [laughs] I started playing and all this incredible shit was coming out. I was just trying things. I kept playing and playing. I had headphones on and it sounded wonderful, just as it does on the recording. I was flying around on the instrument. It was so easy to play because it had light strings.

I thought “There’s nobody out there. I’ve just been playing for myself.” So, I put the guitar down and went into the control booth and realized everyone was completely blown away. I turned to Joe and said “I think I’m ready to record it now.” Joe responded “Man, you’re done. It’s time to go get a drink. You did it.” [laughs] So, we went out, and then came back and recorded this group thing to tag onto the piece. The track was patched together.

It was an example of what could be done at the time. We could take hours and hours in the studio. Costs be damned. It was artistic freedom. We were free to come up with the weirdest ideas, including hiring some kid to play the 12-string—although the truth is, I was already 30 years old by then. [laughs]

Later, I read Joe saying something like “I knew that kid. If the red light was on, he wouldn’t be able to play shit. But without it, he played like a God.” [laughs] I wasn’t aware I was being recorded when I played. Joe was probably right. This was such an incredible jazz-fusion group, that came out of the world of Miles Davis. What a life that was in New York to know all these great musicians. It was wonderful to have been a part of it.

A couple of years ago, I ran into Wayne, John Pattituci and Brian Blade in an airport. Wayne still remembered that session. There’s also a documentary coming out called The Incredible Journey of Weather Report that I was interviewed for. They shot some nice footage of me answering some questions about that session.

Have you ever thought about writing an autobiography?

I’m getting to the age when that becomes a consideration and people have asked me about it. I don’t know how interesting it would be or if I would have any friends left if I did one. [laughs] There are some great behind-the-scenes things people aren’t aware of, like the fact that Jack DeJohnette and I are really great friends. We would have these great big pillow fights backstage and instead of swearing or saying anything awful, we limited ourselves to language like “You no-good guitar plunker!” I remember once during a big ECM tour, Palle Danielsson and Jon Christenson were in the room, fascinated by these two jazz giants hitting each other over the head with pillows. [laughs] Gary Peacock is another mix of someone who is a terrifyingly powerful musician, but also very funny and childlike. John Scofield is another friend I don’t see often, but there’s a real bond somehow.

Jaco Pastorius was someone I also knew. We had some nice moments when Jaco, John Abercrombie and I were on the beach of some French island once. We were there to perform at a guitar festival. We had a day off together. It was a little bit after Collin Walcott was killed. Jaco was very moved by that. He loved Collin. Jaco and I were friends before that, too. There was a whole side to Jaco that was really sweet. Sometimes people point out events within musicians' lives that act as a kind of distortion. Writers sometimes only print the stuff that’s kind of scandalous, when the fact is there’s a lot more nuance. I definitely have a lot of stories I could tell.

What do you see as the value of music and the arts in these very dark, sociopolitical times?

I’m horrified at the political situation in the US. Although I’ve lived in Italy for 23 years, I find it beyond belief. I’m hoping enough people can somehow take on Donald Trump and defeat him. The people who voted for him are in for a slow, rude awakening as they realize this guy has no interest In them. The arts are so important because they are contrary to all that negative stuff. Art lets humans communicate with one another in a creative and amazing way. It’s an important affirmation of our capabilities as a species. It’s abstract. It contains all these emotions and tells stories. It’s magical. Those are the things that attract me to music. I don’t see any magic in the political drive for power. Real music isn’t about power. It’s not about trying to get famous or popular. If those are your goals, they’re completely contrary to the art of making music. It’s wonderful I’ve been able to actually make a living doing music I’m totally fascinated with. It’s very rare. I’ve been able to survive on income from music and I’m very grateful for it.

Before the Iron Curtain came down in 1991, Oregon would play concerts in Poland and other Eastern European countries. We were playing for people who knew us because they had secretly recorded cassettes from Radio Free Europe. Nobody actually had our albums and they didn’t know the names of the tunes. The importance of the music within their lives was amazing. The audience had their friendships and the music, but nothing of any material significance. The emotional intensity we felt from those audiences was incredible. We’d also talk to the audience after the show and it made us further realize what the power of music was in terms of delivering meaning and hope. They wanted to experience what four people could do with music when they had the freedom to come up with whatever they wanted. I’ll never forget that as an example of the value of music.