Donate to Innerviews

Since 1994, Innerviews has provided uncompromising, in-depth interviews with musicians across every genre imaginable. And it does that with no trackers, cookies, clickbait, or advertising.

Your donations are welcome to help continue its mission of highlighting incredible music and artists, without any commercial considerations.

Your contributions will be instantly transformed into stories and videos, and cover hosting and web management costs. Importantly, your dollars will help ensure Innerviews remains absolutely free to all visitors, independent of their ability to financially support it.

Please consider making a donation today by using the PayPal QR code below.

Sheila Chandra

State of Flow

by Anil Prasad

Copyright © 2020 Anil Prasad.

Photo: Adrian Sherratt

Photo: Adrian Sherratt

Sheila Chandra’s meditations on the muse have informed her creative journey on multiple fronts. Between 1982 and 2009, the British artist’s focus as a singer exploring the edges of solo voice possibilities, experimental music and Asian fusion brought her worldwide renown. She’s also the author of three acclaimed self-help books: Banish Clutter Forever, Organizing for Creative People and How to Live Like An Artist. In addition, Chandra serves as a life coach, using her decades of entertainment industry experience to help advise and steer clients towards positive career outcomes.

Chandra first came to public attention in a groundbreaking BBC television drama called Grange Hill between 1979 and 1981, during which she explored important cultural issues related to being an Asian girl integrating into larger British society. She quickly moved on from the acting realm, and while still a teen, launched the groundbreaking band Monsoon in July 1981, together with producer Steve Coe, who would go on to work with her across her subsequent music career.

Monsoon released a single album titled Third Eye in 1982 and had a major global hit single with “Ever So Lonely” which many point to as the most pivotal moment in the integration of South Asian musical influences into the mainstream since Ravi Shankar worked with The Beatles in the ‘60s. But the group’s label and management could barely get their heads around Monsoon’s intent. Its success surprised them all, resulting in many unwanted demands and tone-deaf suggestions, specifically when it came to the gratuitous exoticization of Chandra’s Indian cultural heritage.

Chandra and Coe chose to escape the unwanted pressure and disbanded Monsoon in November 1982. They rapidly moved to launching Chandra’s uncompromising solo career on Coe’s independent Indipop label. Releasing music via Indipop meant they had no-one to answer to but themselves and they pursued a model of licensing its output to other labels.

Chandra released five albums on Indipop between 1984 and 1991. The recordings saw her initially extending the Western pop-meets-Indian traditional music approach she took with Monsoon, but with less extravagant production. She also ventured into more experimental realms. For instance, 1984’s Quiet is a 10-part soundscape that combines wordless vocals and konnakol with sparse, atmospheric accompaniment. Her other work during this period is often recombinant, merging her many vocal approaches with contemporary ‘80s production, Indian classical constructs, and on several occasions, both.

After her first stint with Indipop, Chandra signed established her own company, Moonsung Productions, and licensed her subsequent three albums to Real World. Weaving My Ancestors’ Voice from 1992 and The Zen Kiss from 1994 found Chandra focusing on solo voice and drone work. In addition to her expansive take on Indian music, she also integrated British Isles folk influences, showcasing the two traditions’ rarely-acknowledged shared, historic paths, including the Celtic-Vedic connection, as well as the Celts’ journeys into the Indian subcontinent.

AboneCroneDrone from 1996 was her most exploratory album to date, putting the drone component prominently into the foreground, and sometimes uniquely combining bagpipes and digeridoo with tanpura. A quarter-century later, all three albums, recorded at Real World’s state-of-the-art studios, retain their status as some of the most ambitious audiophile vocal recordings ever made.

Chandra returned to Indipop for her next musical phase, pursuing collaborations with Coe under the project name The Ganges Orchestra. Two mini-albums, EEP1 and EEP2, and the full-length release This Sentence Is True (The Previous Sentence Is False) emerged between 1999 and 2001. The work reflects Chandra at her most mercurial and unpredictable. Their pieces challenge traditional songcraft conventions, sometimes veering into glitch, distortion and atonal territories. Chandra’s vocals also often appear in heavily treated and processed forms on them.

In 2007, Chandra joined The Imagined Village, an eclectic British all-star group founded by Simon Emmerson that combined traditional musics from across the world. The band also featured Billy Bragg, Martin Carthy, Eliza Carthy, Johnny Kalsi, Sheema Mukherjee, Chris Wood, and The Young Coppers. Chandra took part in their first, self-titled 2007 album and tour.

The Imagined Village turned out to be Chandra’s final project as a musician. In 2009, she was diagnosed with burning mouth syndrome, a condition that makes it extraordinarily painful to sing, speak, laugh, and cry. As a result, Chandra made the extremely difficult decision to retire from the world of music. While Chandra does make the occasional public appearance speaking, she does so with intense preparation and recovery.

Chandra turned to the literary world as a new outlet for her creative instincts. By 2010, she had successfully launched a career as a professional writer, with the bestselling Banish Clutter Forever published that same year. Innerviews began its comprehensive series of email-based interviews across 2020 with Chandra by exploring the beginnings of this fruitful transition.

Describe how your journey towards becoming an author began.

The loss of my voice was a huge issue for me, both physically and emotionally. Singers tend to define their identities around their voices. And as speaking was painful, I needed to find another way to communicate. But that wasn’t what was uppermost in my mind. I wanted to find a new profession and a new way to be useful.

I’d already been writing a journal with increasing frequency for the previous 15 years by that point, so I’d probably unconsciously put in some of the 10,000 hours it’s said you need to, to be good at anything. And I joined a creative writing class and did a “How to write a book in three months” workshop that was, by chance, being held locally. Sharukh Husain, the screenwriter of Beecham House, who took the workshop, also described what it was like to be an author. I immediately recognized publishing as being parallel to the music business in many ways. In short, I was pretty confident that I’d “got it” in terms of how to work professionally as a writer. Though there are a few conventions which differ, that has proved to be the case.

One month to the day after that workshop, I had a first draft of Banish Clutter Forever in my hands. To my surprise, writing straight into a laptop felt more and more natural, probably because I was having to communicate with friends increasingly by IM and email rather than speech. When I write books, I feel as though I’m having a conversation with a single reader, and that’s a huge advantage. And although I find formulating the correct concept and tone for a new project hard, the actual writing is generally pretty painless.

What made you want to focus on writing books that help people in their organizing and creative endeavors?

Well, I certainly don’t have the imagination to be a novelist. And as to drawing material from people and situations I know, that feels like a breach of confidentiality or loyalty. I’ve tried creative writing and it contains too many head-scratching, blank moments. Novelists talk of the book’s characters “taking over,” but that never happens to me.

And although I probably seem, from my musical work, the unlikeliest of people to be writing non-fiction, I do have this almost non-neurotypical way of seeing a problem in terms of its bones. And then pinpointing the point of leverage—the one action that’s going to shift the entire thing most easily. I was doing this with friends pretty naturally and thought it might be a transferable skill with writing non-fiction.

I started with home organizing because, as I describe in Banish Clutter Forever, I grew up in a hoarding, clutter-filled household and hated it. But I was doomed to recreate it because I hadn’t learned anything different. In time, I consciously worked out a system that enabled me to live clutter-free with very little effort. There certainly are no daily tidying up sessions. And friends that dropped round unannounced remarked on it and suggested I write it down and get it published. I also felt that my first book should probably be for a more mainstream audience as it would probably be easier to get a first publishing deal that way. From there, writing a book about organizing for creative people and artists was a short leap.

With my second book, I became all too aware that many potentially great artists never have the guidance, explanation of work culture, and networking opportunities that I had as a young singer and songwriter. Organizing Your Creative Career is an attempt to fill that gap. Launching yourself should not depend on how well connected or well-resourced you are, though sadly it often does.

As to satisfaction, I love to be useful. It’s always been my thing.

One of the fundamental principles in Banish Clutter Forever is making the intellectual leap towards “letting go” of things, routines and even beliefs. This is, in fact, one of our species’ biggest difficulties. How does one begin transcending these attachments and how does the book help them progress through it?

I really didn’t write it to be zen in any way. What frustrated me most about all the clutter books I read—while I was still having issues with clutter—was that they assumed you were able-bodied, full of energy, had the time to tidy up every day, and were committed to the house looking tidy for its own sake. In these books, women are encouraged to see their houses as extensions of their own bodies and to be ashamed if their houses are either untidy or dirty. Those were all erroneous assumptions as far as I was concerned, especially by the time I came to write Banish Clutter Forever, as pain severely limited my energy and most of it had to be spent on working, rather than living in some kind of show home.

Moreover, there is a supercilious tone to many of them—a patronizingly middle-class assumption which comes from New Age circles that not being able to let go of things is a result of some moral defect. In fact, many people who can’t let go of items they’ve acquired are being practical. I’m not including hoarders who have an actual clinical problem in this discussion. But if you don’t know when you’re going to be able to buy an item again, due to your financial situation, then it makes sense to hang onto things and repurpose them as much as possible.

In the 10 years since I wrote Banish Clutter Forever, I’ve found myself hanging onto things more. Not because I’ve become a hoarder, or because I live in a larger space, but because I’ve become more conscious of how many resources it takes to create a new object. I have developed a certain amount of intuition about whether I might need an object again in future years, which has both saved me money and meant I don’t contribute to the unnecessary use of materials and energy. Plus I like having to get creative.

One of the reasons modern people suffer with clutter is that the assumption that you will store a certain amount of items is no longer written into our UK housing laws on space and size of rooms—which are currently some of the smallest in Europe. Consumerism as a way to fill a spiritual hunger is also a problem, but not everyone who suffers with clutter is falling into the consumerist trap. A garden to grow food in is no longer seen as a basic need, the way it was 100 years ago. Nor is a sensible amount of storage for recycling. Clutter authors never seem to address this. They tend to follow the neoliberal model which blames individuals for failings, which are in fact, consequences of decisions and laws made far above the individual level. So, here I am in 2020, living in a set of rooms whose size is dictated by a law passed in 1980, when I was too young even to legally hold a mortgage. Mine are not, but if my rooms were a bit full, would that really be my fault?

Coming back to the zen thing, it does frustrate me, the whole “don’t own it, rent it” minimalist culture. It assumes you’ll always have the money to do so—which in a world with a burgeoning precariat class, is not a fair assumption at all. Clutter authors are expected to subscribe to either this minimalist philosophy, or the “here, buy some lovely-looking storage items” approach, because both are a money-making spin-off. The minimalist aesthetic is incredibly expensive to create, and the “rent it, don’t own it” ethos is expensive to maintain. They’re both marketing ploys.

Anyway, I found the apparently prosaic and domestic subject of clutter and home organizing surprisingly political—as the domestic often is. Now, let's come back to the assumptions in clutter books which I chafed against—“able-bodied, full of energy, had the time to tidy up every day, and are committed to the house looking tidy for its own sake.” Interestingly, they’re all concepts which reinforce sexism, even the able-bodied one, which is about valuing women for the state of their bodies and little else. For any Americans reading, this narrative is also contained in the “not necessarily pretty, but admirable, rugged, hard-working farm girl” heroine archetype, which many people hail as quite feminist.

When clutter is not seen as a “female issue,” it often flips to the archetype of Zen monk and suddenly becomes all philosophical, rather than trivial—as it’s supposed to be when it’s seen as a mere domestic one. As usual, neither side of the coin is healthy, and the sexism of regarding the same subject which is trivial when addressed by women, as lofty when addressed by men, is obvious.

Coming back to my own personal take on it at the time, I had this system which worked, and didn’t assume that you were “able-bodied, full of energy, had the time to tidy up every day, and were committed to the house looking tidy for its own sake”—which even Marie Kondo does. My system assumed you were busy, low energy, had some other more important work or purpose, and didn’t want clutter to stop you achieving it.

As to letting go of routines and beliefs, I think routines are helpful to orient you as an artist, as people in lockdown during the COVID-19 crisis are finding. Automatic processes are a great way of streamlining your use of mental energy and husbanding it for more important uses. Even Zen monks have a routine. Regarding letting go of beliefs, I am really not qualified to comment on the matter. Anyone who spends 20 years or more desperately trying to regain a healthy voice is certainly not good at letting go and acceptance.

Is there a larger-scale perspective on how one approaches interacting with society in this era of road rage, endless antagonism and political divides that Banish Clutter Forever quietly encourages, too?

Well, probably not in the way you think. As I’ve said, I didn’t write it to encourage people to be more zen—though I know that’s a tempting assumption to make, given the tone of my musical work.

The truth about “Sheila Chandra” is, and always has been, that she’s a brand. I don’t mean that I’ve been in any way insincere or inauthentic about what I’ve released as a musician. In many ways, I’ve been far more honest and personal about my musical interests than many. But at the end of the day, you cannot represent a whole human being in all their complexity and contradictions to the marketplace. A whole human being will just not fit.

If you know about the alchemy of performance, there’s always a huge amount of projection from the audience going on. One tiny person in a huge place, like Grace Cathedral in San Francisco where I performed solo in 2008 for instance, simply cannot have what people call “presence” enough to fill the space. All performers wear psychological masks when they perform. It’s back to that “not being able to be your whole self in any one given moment” phenomena. And in some ways, the more archetypal the mask you wear during a performance, the larger your presence becomes. Mine as a performer was pretty archetypal and so people projected onto it a hell of a lot. And what they projected was influenced by the nature of the music. Indian classical and drone-based musics have always had a spiritual connotation—and in part, that’s practical. Those forms of music really do help you become more contemplative. It’s built into their structure.

Throughout my career, I’ve always been amused by the slack-jawed and slightly appalled way some people have regarded me while I’m making a practical and probably quite ruthless decision, though I’ve never been ruthless when it comes to the way I treat other people. They’ve expected me to float in on a cloud, never be angry or stubborn—I’m both at times and especially stubborn when protecting my work—and be hopelessly vague in my notions. But being like that isn’t going to gain you success in a competitive field like music.

In real life, I’m incredibly matter-of-fact, and practical. I always have been. What listeners hear when they explore my work, is my secret world—the one where I don’t have to be practical in what I envision, though recording budgets were still a practical factor, obviously.

So, now we come back to your question—on a micro level, yes. The things you’re talking about are usually the result of a buildup of stress. Stress in itself is not bad. The stress of performance can be exhilaration or crippling nerves, so it’s all a question of degree. What I think many people feel—and let’s face it, here I particularly mean men—is the buildup of stress that happens at a subliminal level when your home or workplace feels physically like a hostile environment. Men are generally encouraged to think this is a trivial matter because it’s too “feminine” and “domestic.” And there are consequences for men in thinking like this, including ruining their health and not thriving when they don’t have a female influence in their lives.

When you disregard the body, and shut out its feedback, so that you can be tough, the pain—in the sense of stress—doesn’t go away. It keeps building up in the body. And in the short term that overflows as temper—road rage and political antagonism. In the longer term, it comes back as ill health. Continually being too cold because you’re too trendy to have curtains, or suffering bare lightbulbs at night or living in constant ambient noise and wearing out your knee joints because you’re too trendy to have carpeted instead of concrete industrial floors all takes its toll.

It’s been said that the opposite of “rape culture” is “nurturance culture.” Until we stop trivializing the domestic, and stop trying to pretend that it’s a "philosophy" rather than something practical our bodies need, we won’t “get” this as a culture. And ironically we won’t be very zen either, unless we spend as much time as monks do, perfecting their state of mind.

What about the element of breaking away from consumer culture when we are now being micro-targeted by social media and data modeling to persuade us to buy more and more? Is that a different kind of clutter we also need to banish?

Most definitely, yes—though it’s not something I addressed strongly in Banish Clutter Forever. It would have taken a whole other book to do so and I’m not sure I’d have been qualified to write it. The key is, what is it you’re trying to buy? What gap are you filling? Sometimes this takes years to work out. And even when you do, that doesn’t always stop you buying for that hunger. And the hunger can change as you age.

Since my voice has become painful, my sense of control over the ways I can make my life better has been eroded. And buying unnecessarily has become a way of circumventing my frustration—though I do curb the impulse most of the time. When I buy unnecessarily, it’s often for me about a concrete way of “upgrading” which isn’t constrained, the way I am with larger issues like health. There I cannot “upgrade.” I can’t buy a new and painless mouth and throat.

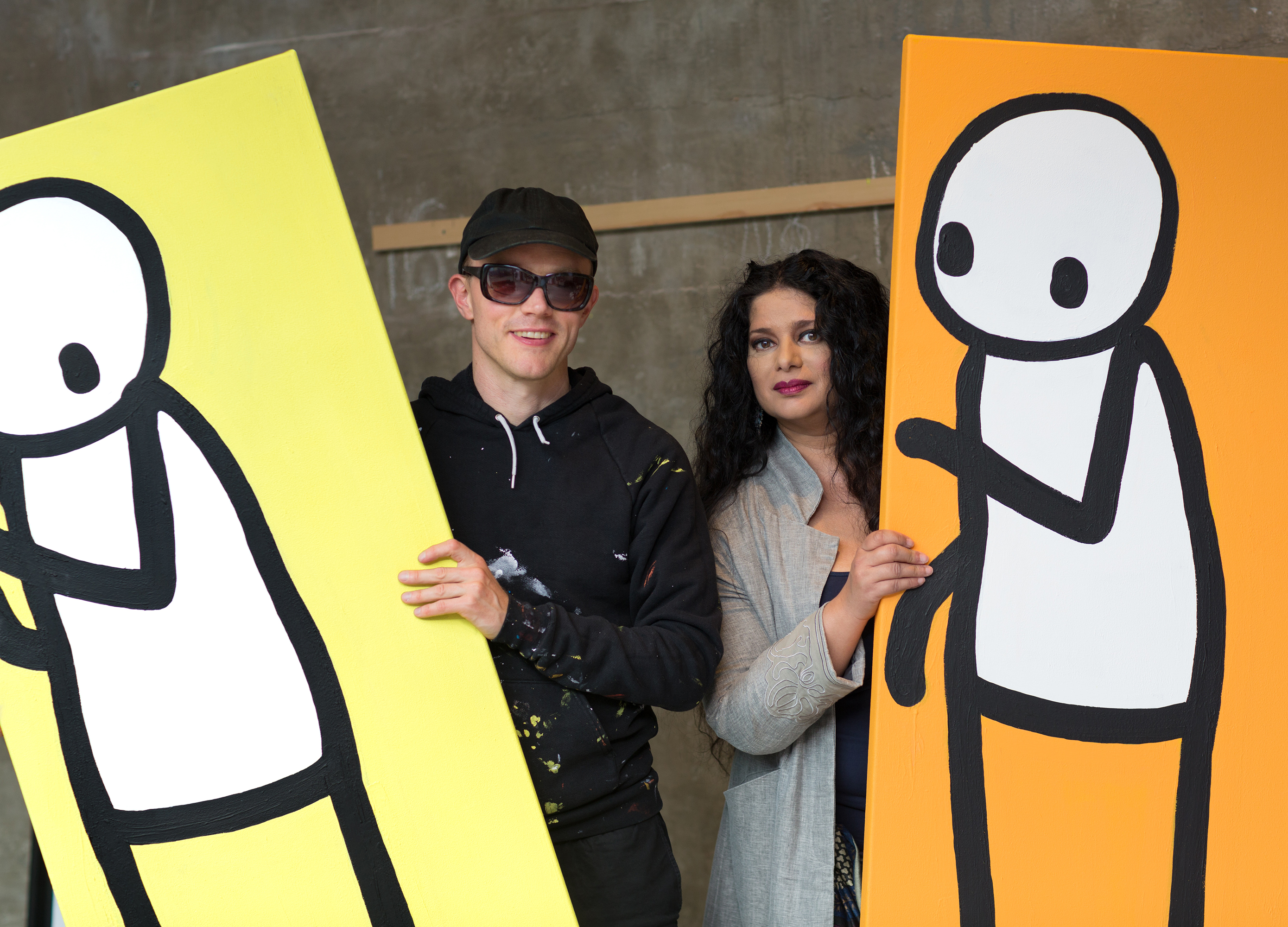

Stik and Sheila Chandra, 2017 | Photo: York Tillyer

Stik and Sheila Chandra, 2017 | Photo: York Tillyer

Tell me how your interactions with the renowned street artist Stik led to writing the Organizing Your Creative Career book.

Stik is such a star now that people find this hard to imagine, but when I met him in 2008, he was homeless and squatting and had been for 10 years. I was still a singer with an international career. But that difference in status didn’t matter because we didn’t meet in a professional context. We met at a club night and he asked me to dance. He’s a great dancer, and I love to dance. So, he asked me again.

I was saving my voice for a concert in Bristol the next day, so I was communicating by note. And though most people found that off-putting, he didn’t, because he drew me little stick figures in reply. So, we got talking in a sense, though not about the arts particularly, and swapped numbers. And every so often I’d visit him while I was in London on business and I would occasionally invite him to stay with me in Somerset.

It sounds like an unlikely friendship but visiting him in squats didn’t faze me. I’d grown up in inner-city London in the ‘70s and known plenty of squatters. I’d lived in pretty terrible housing myself, though mercifully, not for all of my childhood, so I knew the drill. If there was no running water or the kitchen was flooded, I didn’t think twice about it. I also knew that getting out of the squat environment was going to be helpful for Stik. He told me when we met that he hadn’t walked in the countryside for four years. And I knew that being somewhere physically comfortable, even for a few days, and having a mental break, would give him perspective on his situation.

At that point, he had been painting on the streets in the East End of London for 10 years. So, I used to give him the odd piece of artist advice. And then he found out about my career and started to take that advice very, very seriously. But, of course, every piece of advice cost me pain, because any speech caused me pain. So, I decided to write a brief handbook for him. Now, Stik is dyslexic, so that probably wasn’t the most brilliant idea, but anyway, I wrote it all down.

I mentored Stik for a number of years. And he’s gone on to became one of the most famous and collectible street artists in the world. By the time he’d become established, the state of my throat and mouth made it impossible for me to sing, but I was writing books. So, he nagged me over a period of years to expand the book I’d written for him and get it published so that it’d help other artists. I think he also did it for me, because he could see that I’m happier when I’m creating something.

I’ve been around many brilliant artists whose entire lives are a shifting state of chaos, organizationally and creatively. One of the things Organizing Your Creative Career seeks to do is debunk that this is a naturally beneficial or necessary state. What’s your take on people who insist on holding on to this idea and what do you think they’d experience if they took your advice?

Unfortunately, for filmmakers and authors, physical chaos is a neat little metaphor for the swirl of creativity. So, genius creators tend to get consistently portrayed in that way, whether they were chaotic or not. After all, what is visually exciting about Jane Austen writing on small A6 letter-size pieces of paper, one at a time, at a small wooden wedge-style writing desk on a tiny table, as we know she did? Doesn’t look nearly interesting enough for the most accomplished novelist of the age.

And we take this imagery in—all of us. Some people feel as though they don’t have a right to claim the term artist and unconsciously surround themselves with chaos to prove their credentials even to themselves. Others have been fed the myth that artists have to suffer in order to create great art. Well, I think they do, but not in the way you’d think. Artists don’t have to be junkies, sex addicts or tormented with emotional pain to create great art. All that tends to get in the way. But they do have to commit the cardinal neoliberal sin of going against market forces to deliver more than was required of them or than they’re being paid for. And over a lifetime, following that path means many sacrifices of many different kinds, like people thinking you’re bonkers for a start.

Some people think that the only way to be edgy is to not take care of themselves, or be lackadaisical about their careers. I call this Lord Byron syndrome. He feigned carelessness to others, but worked hard at his image in private. Really edgy work takes a lot of boring hours when you don’t appear to be achieving much, half the time, but people still believe this myth. Or that they’re more of a man if they’re “chaotic.”

Others just fall for the emotional blackmail from people around them about how an artist is supposed to be. I remember a record label phoning me in the ‘90s asking if I’d grant permission for two of my tracks to be on their compilation at half the usual royalty rate. I said no. This lady then spent 10 minutes ranting and telling me she’d never had an artist say no because of money! She spat the word out as though I should be ashamed for asking for the going rate, when in fact, making a financial killing was exactly what she was attempting to do by stiffing an artist purely for money. So, ever obliging, as I was obviously destroying her world view, I said “Well, I’m also a music publisher if that helps?”

There are also people happier with a busy visual style. They don’t like pristine minimalism because it feels cold and uninspiring. Others like the comforting illusion that comes with not counting how many projects you have on and not remembering them all at once, and therefore believing that that means that you’ll never run out of ideas.

If you like chaos, I have no problem with that. I’m not trying to convert the world. I’m trying to give artists tools that work for them. And the problem is, most books on creativity and organizing are written for the business world. They’re not about the challenges artists face at all. Artists of all kinds have been rightly afraid that those sorts of organizing tips would lead them down an uncreative road, and they were right. However, I’ve written a book that does contain useful artist tips that won’t suppress that whirl of creativity because I hate chaos and I guessed there were a fair few other artists who do too.

My suggestion to any artist is pick a problem area and have a go at implementing some of my suggestions for it. Does it work for you or not? Are you in better health, better rested, more productive, or coming up with better ideas? Do your commissioning clients or organizations trust you more? That’s the litmus test.

A complex topic you explore in Organizing Your Creative Career is pricing and funding. Provide a snapshot of the behaviors and shifts the chapter encourages, and why they’re essential as considerations in the modern era.

Basically, my thoughts are:

First, attitude. If you make good work and people want to buy it, you’re a professional artist. No denials, now! Total up how much it actually costs you including labor and overheads to make the work—don’t skimp—and aim to charge at least that. This is not vanity. This is the cost of your work. Our post-Reagan/Thatcher world has divorced labor from the cost of living and produced an underclass of workers who are constantly one financial problem away from destitution. Don’t think like that yourself, even if it takes you a while before your market can stand paying you a decent wage.

Who are people turning to while healthy, in the lockdown? Artists. Writers. Sculptors. Painters. Playwrights. Screenwriters. Actors. Musicians. All the people they said were “not useful” to society. Don’t forget that. But knowing this alone "butters no parsnips” as they say. And if it takes learning how to make your work worth investing in for collectors, then learn the system in your field.

With funding, think like a psychologist and an advertiser. Getting funding either from arts bodies or the public is a distinct and often all-engrossing skill. It has little to do with actually making the art, which is the sad thing. Learn the tricks and apply them.

Why is it essential? A professional artist sells work—and that gives them the luxury of concentrating on it for long periods, which in turn makes them a better artist. Making a decent living is not an afterthought or an irrelevancy. It’s an essential means by which you give your art to the world and sustain yourself to make more.

How do artists fight the myth of “exposure” from “free work” in this age of entitlement and manipulation as it relates to their second-class societal status?

First, weigh up if what you get is actually valuable to you or your career right now. Occasionally it will be. Most times, not. I outline how to weigh this up in the book. And how to take an opportunity that’s not worth much in terms of exposure and turn it into one that is.

But it has to be said—there are some situations where a large corporation that has the money and should know better, and who is paying its cleaners and caterers around an event the going rate, will ask you to work for free. It’s all very well for me to get on my high horse, as I’m no longer a working musician, but what I would say is “think solidarity.” You may not be in a union, but if you undercut another artist, or allow yourself to be undercut, you lower the rates for everyone. Permanently. How are you going to make a living then?

As to combatting second-class societal status, as the COVID-19 inequalities have proved, that ship sailed long ago. Those who really keep society functioning, such as cleaners, farmers, fruit and vegetable pickers, healthcare workers, refuse collectors, supermarket workers, postal workers, delivery drivers—and yes, artists of all kinds—have always been undervalued and, with a few megastar exceptions, underpaid. Just look at who, as a society, we pay fabulous amounts to, and who we lionize. We’ve got it all backwards. And I don’t believe the lockdown will change that. People in power will conveniently forget this as soon as possible afterwards.

I found the “Long-Term Maintenance and Challenges” chapter very useful. I know many artists who seem to think they need permission to take care of themselves. Why do you think this situation continues existing and how can artists get past it?

It is, as you guessed, the old “suffer for your art” cliché, which along with the old “the show must go on” cliché have been put about by promoters and others who benefit from the work of artists and don’t want them to take a sick day. The arts are full of emotional blackmail and mind games, not least because there are few unions and everybody is a freelancer or private company with their own interests and no legal obligation to take care of “outworkers” like artists. It takes a while to work out what people’s agendas are.

But in short, my advice to artists is, never ever work if doing so will do you permanent damage, even if it loses you an important client. Yes, they’ll probably try to emotionally blackmail you, but you cannot replace your body and without your body, you won’t be working for anyone.

Artists have particular physical and emotional ongoing needs which I wanted to write about. These are rarely covered elsewhere, so it was important to include them. They need to be encouraged to take the long-term view, because if they’re successful, they’re not going to want to stop, just because they’re 70 and a bit stiff. What they do in the early years really affects them later on, so they need to plan.

Of course, when we’re 20, we all think we’re immortal. I wanted to remind my reader that your fifties come surprisingly fast. And I think there’s a macho thing going on here, too. It is not “girly” to feel pain, take notice and deal with it—whether emotional or physical. It’s simply practical. That’s why I refer in the book to the artist’s body and mind being “plant”—the machinery they will use to produce work. You’ve got to take care of your production line machinery or your career will be over.

I’ve heard Stik chatting to some street artist on the bus and the bloke—it’s almost always a bloke—saying his girlfriend “takes too much care” of him. And Stik, being relatively older, had to put a brotherly arm around the chap, metaphorically, and tell him that rather than being irked and embarrassed by that, her caring is going to help him to stay healthy long-term and that it proves she’s a keeper. It’s as though these young men need permission from an older man to understand this. The young guy certainly wouldn’t have listened to me. And I hesitate to think how truly rubbish his “nurturing his girlfriend in return” skills are.

Many people from across all walks of life typically condemn an artist’s life as societally inessential. Describe your intent in helping people understand the myriad benefits of applying the artistic mindset to other realms of existence in your latest book How to Live Like An Artist.

It’s a very simple everyday practice used by many artists, but you don’t have to be a professional artist, or even have an artistic calling, to reap the benefits of it. And it brings you to an immediately more peaceful and less fearful state of being. In fact, it brings you back to your authentic self and instincts, and that state of flow we all crave. All this is free and instantly accessible. Many of us have just forgotten how to do it.

In part, I wrote it because it seems to me, the answer to most social ills—addiction, and all the public disorder that ripples out as a result, as well as abuse, violence, toxic masculinity, racism, ableism, classism, and mental health issues—is connection to the self and others. Between those two, you have to start with a connection to yourself. Where this connection is missing or damaged, you find people who are vulnerable to being taken in by conspiracy theories, joining cults and falling prey to supporting colonization, and fascist or authoritarian ideologies. Where you have people who don’t know themselves, they carry an inbuilt fear which is projected outwards onto others as various forms of violence—in the wider sense of the word, such as a punitive benefits or justice system—which they feel their fear justifies, in other words, the popular rise of the right. On a more minor level, you find people who feel life is meaningless, feel alienated and lonely, are unable to spend time alone or enjoy anything without consuming, for whom no amount of money is enough, who don’t trust themselves, who alienate others, who can end up blaming others or a particular group for their ills, and are running from an internal emptiness.

Though it’s not the subject of the book, I want to emphasize first that connection to others is supremely important—and only empathy for others will enable us to reform systems that currently penalize the poor, disabled people, women, children, the elderly, Black and Brown people, LGBT people, and so on. But you cannot have empathy for others without first understanding and being kind to yourself.

Over the past 400 years, we’ve built a ruthless and violent system based on capitalism involving trafficking, rape of resources and violence against indigenous and colonized people. Though we may not be the victims of the system, it has consequences for us, too. Among other things, it means we internally measure a person’s worth by their productivity and endow them with status, honor and power accordingly. We devalue, malign and mistreat those that don’t have these things. And this eventually leads to violence against the self.

Life means loss. It’s inevitable. What happens if you “lose face” or status? What if people no longer respect you? What if others defy your authority? What if you become disabled? What if you lose your business, job or profession? What if you lose your strength and energy? Or your looks? What about when you’re old? What kind of violence against yourself, your body or against others, will your desperation to gain your “place” back, lead you to do? What does your internal voice say about yourself all day long? What are the very real social, societal and support consequences of your “fall from grace?” And perhaps most importantly, what unwitting violence will your lack of empathy and feeling for your own humanness lead you to commit against others in your power, on a domestic and on a national level?

These are issues ideally worked through by and with activists and therapists. But people aren’t always ready to engage on those levels—sometimes because, to their disadvantage, they are associated with being emotional and with the “left.” On a personal level, it’s no use asking myself why I’m not politically or emotionally literate enough to address these issues like activists and therapists, though I frequently do. Better to contribute from what I know. For me, there is a humble and simple way of working on your connection to the self, especially if you’re a person that lives in your head, as I do—and that’s to start by listening to yourself in very practical ways—the ways that artists have always used.

As an artist who’s lived this for 40 years, I can give the reader tools which point the way back to that connection with the self, connection to inner-directed time and to a blissful sense of “flow,” connection to the body and your energy, gentle connection back to your emotions, and to the “wondering” mentality that you had as a child. It doesn’t involve emotions and it doesn’t involve ideology, which is a huge advantage. The only person you’re allowing to guide you is yourself and that helps build trust in the process. It’s the space where new thoughts are possible and empathy and common sense are most likely to prevail. In living like an artist, a new trust in one’s instincts can be born, and in being creative, a new sense of self-respect, unconnected and independent of consumerism and financial status—and therefore one not in others’ control—can emerge.

Peacefulness, being in tune with oneself, a lessening of the “busy, anxious” mind, natural self-care, respect for the body and energy, and finding your own voice, start to manifest. Of course, if you want to take it further and go to therapy or educate yourself on social issues, all well and good, but this is a great starting point.

Living in a more instinctive and connected way is our birthright. Capitalism has tried to destroy it, because people won’t work to the clock, in jobs they suspect are worse than useless, if they have a practical, including the financial, means to live in a more self-connected way. A society based on capitalist principles is always going to ridicule and suppress artistic endeavor which reacquaints you with that connectedness. It has to do so perpetually. Because the flame inside you is both unique and yet common to every human being ever born or yet to be born, so the “danger of revolt” is always present as long as human beings survive.

Our current systems have to work very hard in fact to suppress those creative, connected instincts. They would have you believe that the arts are “inessential.” But when COVID-19 hit, where did most of us turn? To plays, movies, TV, novels, blogs, storytelling, and design in the form of home improvement, crafting, non-fiction, comedy, satire, good journalism, online club nights, biography, documentaries, music, and visual art in order to either find comfort, escape or make sense of what we were going through. Could we have managed this time, or even everyday life, when you think of the ubiquity of art and music in restaurants, and TV in our homes, without them?

The arts and the imagination are the essence of what it means to be human. Whether to celebrate or to mourn, or to somehow live with the senseless and unfathomable, we turn to the arts to help ourselves to do it. But more than that, artist practice is an ancient way of accessing an instinctive form of emotional healing for both ourselves and those we affect. This is what I wanted in an almost deceptively simple way, to make accessible to everyone. It’s by no means a whole cure or an end. In fact, it’s almost ridiculously gentle and personal, but a sea change within is where things actually shift. In that way, it’s a valid piece of the puzzle of bringing us back to our empathy and “ourselves.”

For some reason, lots of people believe artists lack discipline, when in fact it takes extreme discipline to really get this work done and have it manifest itself in public view. Why do you believe that is?

Well, the short answer is because they don’t understand the process. This is likely as a result of three factors.

As we discussed, there has been an unfortunate tendency to use “chaos” as a lazy shorthand visual metaphor for the creative process, especially in novels and film. Secondly, as you mentioned earlier, it’s been represented as an intrinsically “unhealthy” practice—one that involves addiction, obsession, a need for attention, and pain as an intrinsic part of the process. I don’t mean to assert that there weren’t as many artists with mental health problems as you’d expect to find in any representative slice of the general population, but the real problem with many of the artists that suffered these ills, was most commonly that they were working within a hostile capitalist system which not only made things harder for them, but also constantly sought to misrepresent artistry for the reasons I outlined above. Thirdly, a lot of the work artists do happens beneath the surface. It involves a lot of learning, showing up when you’re not producing anything good, and then often, though not always, having a breakthrough. But the breakthrough is just the tip of the iceberg. It doesn’t happen without the showing up even when the work is rubbish.

Finally, I think there is a general distrust of anyone who doesn’t have to work at something they at least mildly dislike. Unfortunately, this is the state most employees find themselves in, and it can lead to the general public believing that anything that’s less than unpleasant “isn’t work” and that given the chance to direct themselves that they’d skive, so that must be what artists do all day. It’s pure projection.

Ironically, they’re doing themselves a great disservice when they believe this. The truth is, most people like to be engaged in meaningful activity, whether it’s improving themselves, caring for others, making the world a better place or producing something of beauty. Most universal basic income trials confirm this. In fact, life can be flavorless when we lack these things. Loss of life purpose is a major factor in depression, even surprisingly when it’s the result of a huge lottery win. A better analogy to help people understand would be that arts projects are like children. When you’ve created them yourself, you’ll go through a surprising amount of discomfort and sacrifice, and display a great deal of bravery to “protect” them. And they can be incredibly hard work, hugely rewarding, and when raised well, of great benefit to society at the same time, even though the work is unpaid.

The British government recently went on a full-on assault against the lifestyle of artists with its “Their next job could be in cyber, but they just don’t know it yet” campaign. What’s your reaction to this?

In 2020 in Britain, we have a conservative government that has been hijacked by its right wing elements. Even older conservatives are saying they don’t recognize the party. This government is blatantly corrupt, self-serving, incompetent, and institutes policy not based on science or evidence, but purely based on right-wing ideology and where that policy makes it possible to siphon off public money for its donors and cronies.

Regarding the former, it has, based on right-wing ideology alone, decided to “starve” artists much as it did with coal miners in the early ‘80s. Our arts industry is world beating. We’re the land of Shakespeare and The Stones, and Stormzy and Sheeran. We earn £10.8 billion for the UK every year—ten times what the fishing industry does and we’re an island. It makes no sense to hand out money to other industries and not support this one from its grassroots up. There have been grants to some larger institutions such as the Victoria and Albert Museum, the Tate, and The National Theatre, but from what I’m hearing, many artists and arts freelancers have not been able to access the SEISS (Self-employment Income Support Scheme) grant. Arts events companies who have invested in tens of thousands of pounds worth of equipment to fulfil a fully-booked summer season at the start of 2020 have majorly lost out, and it’s artists and arts technicians on the ground who are suffering. As many as two thirds of them are considering permanently leaving the arts. Without them, much as when you’re farming, if you destroy worms and the good microbes in the soil, you don’t get a crop of much actual art being produced.

The conservatives did this with the miners in the ‘80s because they had strong unions and Thatcher wanted to destroy them. Generally, the arts are made up of freelancers and are not unionized. But right-wing movements, and actually any strongly authoritarian governments, even if supposedly left-wing, fear the arts and artists because we question and get people to think. Their rhetoric, dogmatism and scapegoating of minorities and fear-mongering doesn’t work so well when there’s a strong critical voice from artists opposing them. They’ve already hijacked the media, which has allowed and facilitated the rise of the right in many countries. Our Brexit decision followed a 30-year campaign of lies and scapegoating of the EU in our press, for instance. Artists are next, probably because we’re the only threat left.

The hypocrisy of attacking the arts as unviable and advising those associated with the industry, from producers down to event managers, best boys and runners, as well as all the creatives involved, to “retrain” at a time when the only thing that’s got us through lockdown is arts content, is breathtaking. It’s so obviously a lie—but it’s one that builds on a society-wide foundation of a feeling that has always simultaneously worshipped, fetishized, impoverished, and denigrated artists.

The emotional undercurrent of our connection to artists as a society has always been dodgy. We distrust people who create something out of nothing as if it’s a trick or not real. As if it’s not some of the hardest work human beings ever do—perhaps not physically hard, but when done well, mentally and emotionally exhausting. Collectively, we very happily dispute the idea that artists are entitled to a reasonable living wage, holidays and time off for illness. Sometimes we deny they’ve a right to be paid at all. Yet we criticize when artists aren’t superhuman, suffer from stress or have an off night. We both disdain and envy—two sides of the same coin. We don’t actually regard artists as human—they are both a high and low ace, all at the same time. This is an unfortunate side effect of the “magical” and transporting effect our work can have.

Unfortunately, a lifelong basic distrust of “Johnny Foreigner” born of our British Empire mentality and a woeful lack of real education about what the empire actually did was a strong emotional base on which to scapegoat the EU and immigrants, and to build the movement for Brexit. This is a formula that the right already knows will work. I fear our age-old collective and blithe dismissal of artists will form a foundation for the basis on which this government will persuade Britain to happily stand by and watch, or even cheer on the destruction of the arts industry over the next couple of years.

That said, the infamous “Fatima” poster advising artists to retrain which you refer to, was endlessly, mercilessly and hilariously lampooned, satirized and repurposed almost instantly and shared all over social media. Well played artists, well played.

ABoneCroneDrone photo shoot, 1991 | Photo: Aditya Bhattacharya

ABoneCroneDrone photo shoot, 1991 | Photo: Aditya Bhattacharya

Contrast the experience of your music being reviewed by music critics and your books being assessed by literary critics.

Literary reviewers of non-fiction can be very plain and fairly objective with what they liked and what benefited them. On the other hand, unless they’re reviewing a book as a fan, they’re unlikely to read the whole thing in full. So, the good stuff at the back gets missed out, which is a shame as sometimes the most useful stuff is in the back.

Record reviewers have usually listened to the whole album. But then it’s a question of taste, and whether they get it. What they describe for the reader is ephemeral. It’s hard to paint sound in print. So, then we come down to references and connotations. Music critics usually know all the references that are likely, and name them even when I’ve never heard of said influence. That was very common with me. I wasn’t then, and am even less so now, a big consumer of music. And connotations are a bit of a minefield. For instance, take the word “exotic.” Aren’t they just using that because it’s an easy word to reach for while not being too alarmingly specific? The question becomes “Exotic for whom?” For the second-generation Asians who have grown up listening to Hindi film and Indian classical? Nope. “Exotic” as a connotation presumes Western culture and Western audiences as a “norm” and fetishizes and devalues the artist concerned. I was once referred to as the “fair trade” option—in other words, “higher quality” within World Music. And the journalist meant it as a compliment.

As to the current state of apartheid around World Music—don’t get me started. At least as an author, my books are not in a separate section because I’m Asian.

Tell me how you came to terms with your burning mouth syndrome (BMS) diagnosis and it leading you to conclude your career as a musician.

At first I didn’t have a diagnosis. I thought it was a side effect of some specialist vocal physio work I was having done. I went to see several ENTs and a nerve specialist over a period of two years, but none of them could name what was happening accurately. I gave up singing because I just couldn’t continue. Then I happened to read an article about BMS and realized I needed to contact my dentist.

At the point in time that I developed BMS, I’d already been struggling with throat pain for around 18 years. My vocal chords were scarred during a clumsy intubation while I was being operated on to save my sight in 1992. I was able to sing for gigs, but not really enough to continue writing and exploring music the way I wanted to. I’d have to go whole summers without speaking to anyone if I was gigging, so that I had enough pain-free time to rehearse and give concerts. When the BMS was added to that, it was just all too much.

Instead of being able to talk for roughly three hours before the throat pain kicked in, the BMS started after five minutes and got steadily worse. It is so painful with the two pains together that I can’t rehearse anymore, which I do feel guilty about. It’s sort of like I’ve left a Stradivarius in an under-stairs cupboard, to rot.

As for transcending it—I’m not sure you ever do. That’s an ableist assumption. It’s a very neat and comforting thought for other people—the idea that you move past it, but you don’t. My social life has been severely curtailed. I will never be able to live with a partner, ever. And that’s a depressing thought. Every social occasion has to be planned for carefully with days of absolute silence in advance, and days of pain afterward, which feel like a punishment for daring to have fun at all.

People talk as if a voice is something I can leave behind. With a singing voice, that might be true. With my speaking voice as well, it’s a constant loss—an ongoing set of experiences, and pleasures I cannot have. “What’s the secret of your strong relationship…?” “Oh, we talk a lot!” “How to maintain your physical health and stave off Alzheimer’s? Develop strong and close relationships.” These bits of advice frustrate me all the time.

Finding speech painful is a disability that most people just do not consider and are not sensitive to, even when they try hard. They’ve absolutely no idea what it does to your mental health not to be able to communicate normally. I had a folk singer friend who overused her voice and was told not to speak for two weeks. By day eight, she was saying “This has eaten my soul.” And when you’ve been a relatively high-profile singer, it’s all anyone ever brings up. It’s finally tailing off a bit now, but imagine after you’ve lost your hair permanently due to a terrible illness and for years afterwards the first thing everyone brings up when they see you is the loss of your hair, and how wonderful your hair was, and how much they loved it.

Have you considered making music in ways that don’t involve your voice?

I briefly considered what my options were. But I used to write with my voice. That’s why those vocal parts were so special. They’re not transposed from something else or even from another voice. I don’t play another instrument. And a cruel feature of the larynx is that it silently mimics sound—it actually moves—when the brain “thinks” a sound. So, if I wrote music I’d still be hurting my throat.

Monsoon Third Eye photo shoot, 1982 | Photo: Fin Costello

Monsoon Third Eye photo shoot, 1982 | Photo: Fin Costello

What are some of the highlights of your Monsoon period for you?

Well having a hit is fun—no question. And for me, as a 16-year-old kid who’d been bullied as the outsider for various reasons, suddenly getting attention, being respected and being in demand was a huge high. I was an outsider because I was Asian and one of the few, if not the only introvert at a theatre arts school. It only lasted six months, but perhaps that was for the best. I had the joy of recognition without the lasting intrusion of fame, though throughout my life, I haven’t been afforded the privacy most people take for granted.

People tend to assume that you want your name broadcast to the group in any small gathering such as a folk club, where you’re just there to listen, because if they were in your place, they’d want theirs broadcast. That’s not how it works. It makes speed dating both hilarious and horrifying by turns though. And I’m not even really famous! At least I didn’t get chased by reporters, have my bins gone through, have people camped outside my house, have family members and friends pumped for information, have my phone tapped, or get trolled on Twitter.

Just as an aside on the privacy issue, I developed Lupus and lost all my hair last year. I didn’t realize how much of a touchstone that huge mane of dark wavy hair was, in terms of how even friends picked me out of a crowd. When I first went out after having had to shave it all off, part of me was delighted. I thought “Oh my god, nobody knows who I am!”

But the more serious answer to your question is about what having a hit bought me. Freedom. Not financial freedom. The Monsoon deal was awful and I’ve never received a penny for any of the Monsoon catalog except for tiny personal advances at the time. But being one of the few World Music artists to have a hit in her own right and not as a result of collaborating with an established mainstream music star, was a formidable accolade to have. I should mention that the term World Music term was not even invented in 1982 when “Ever So Lonely’ was a hit around the world, pretty much everywhere except America.

Having a hit meant people in the business took me seriously. It meant I could, at least for the early ‘80s, get a meeting with pretty much anyone I wanted to. More importantly, it enabled me to do something not many artists even then, had the luxury of doing. It enabled me to “cash in my fame chips” and use that fan base that remained loyal, to fund the experimental Asian Fusion work I was doing. I was the only full-time Asian Fusion artist in the UK throughout the ‘80s and that was how I was able to make it work without playing live.

I didn’t want to play live at that stage because it wasn’t my forte and because I knew I wouldn’t learn as much about my genre if I was playing the same songs night after night for weeks or months on end. I made four solo albums in two years instead.

There was no audience in India in those days. But my reputation translated into just enough selling power that I could make those first four solo albums which established my credentials as an experimental artist. It took personal sacrifice, at a time when everyone just assumed I was sitting on a pot of money from having just had a hit, but it was what I was determined to do.

Early in your career, it was suggested you choose the name “Boo” instead of using your real name. Tell me the tale.

It was just one of those silly record label person suggestions. When you’re 16 and it’s your first band, and no-one knows who you really are, they try to construct an image for you. It was common for young female singers to go by a quirky forename, and so the head of the label suggested it. My mum said no. And few people argue with your mum.

Looking back, I do think it was a strange suggestion. Monsoon came with a whole trunkful of culture, history and connotation, not as a band, but in terms of what they were and what I was drawing on. I was by no means a vacuous blank page of a teenage singer in that sense. But Phonogram didn’t seem to be able to cope with the huge background of cultural riches we had to draw on. They treated Indian culture as if it was a two-dimensional fashion choice, which is what culturally-appropriating Westerners reduce it to. They also could not regard me as neutral. I think the suggestion to call me “Boo” was an attempt to make up a simple—for them—understandable background of some sort for me. Very strange.

However, that tendency to see an Indian influence as a fashion choice, suitable only for a single season, was what ultimately contributed to Monsoon’s break up at the end of 1982. Phonogram wanted us to “drop the Indian influence.” They could not see that it was our raison d’etre because they regarded it like a curry paste in a jar—and wanted us to get back to “normal” cooking.

How did you personally cope with being the object of unwanted exoticism obsession at the height of your music career?

Very badly. The first thing I experienced at 16 was erotic exoticizing. Miss India meets the Kama Sutra meets the harems of the Arabian Nights—that was the picture most men had in their heads. I’d grown up in a very religious Christian household and had not been encouraged to think about sex at all. As a teenager and young woman, I had no idea what was passing in the minds of the men who erotically exoticized me, and that’s probably a good thing. But I did know when they were doing it. Creepy and disgusting. I didn’t feel safe being alone in professional settings.

As to being exoticized per se, in a way, at the beginning, I benefited from a very rare point in musical history. That point where there was an audience open minded enough to listen to Monsoon, but before the music business and journalists rushed to categorize and compartmentalize what came to be known as “World Music” to the point of commercial apartheid.

After that moment passed, I just had this constant Groundhog Day feeling of “Why don’t you treat me the way you’d treat any other artist? Why do you assume I’m a 'natural' rather than that this technique has taken me a decade or more to learn?" I grew up listening to Bing Crosby, Des O’Connor, Max Bygraves, Gracie Fields, Queen, ELO, The Jacksons, and Aretha Franklin just like everybody else for goodness sake! Why is every question asked through the lens of gender, race and otherness? Why is my later work not considered “New Music” and not taken seriously in that world? Is it just because I’m not White, male and in my fifties? It was just very frustrating. I’m not a very patient person. It was constantly wearing.

Monsoon Third Eye photo shoot, 1982 | Photo: Fin Costello

Monsoon Third Eye photo shoot, 1982 | Photo: Fin Costello

What goes through your mind when you look at photos of yourself from the Monsoon days?

To be honest, it’s so long ago that it feels like it’s another person. As women, we’re all encouraged to look the way that we did as teenagers forever, and when a certain period of your life when you were as good-looking as you’re ever going to be is highly documented, then there’s a temptation to harken back to it. But I can’t be the same and it’d be a bit weird if I could. And anyway, who’d be 17 again?

Often I’m tempted to disavow that part—the musical part—of my life. Not in the sense of being ashamed of it, but simply that I don’t feel entitled to own it as an accomplishment, or certainly not one that I continue to trade on personally for self-esteem purposes. I have a horror of being that person who constantly “dines out” on something they did 30 years ago.

What you don’t realize when you’re 20 is how much you’ll have changed by the time you’re older. Change and fast growth are seen as things that largely happen to the young. But the fact is, you feel like an entirely different person, especially if you’ve kept up with your personal growth.

So, in a sense it’s not “me”—certainly not the current “me”—who created all that stuff. Nor do I have the sense that it’s the current “me” who was ever a musician. That seems so far away now. I think it’s in part because I can no longer make the noise. My mouth and throat are so painful that I haven’t been able to warm up properly and consistently for about 10 years. If I try to carry a tune, I’m rusty. It’s an odd and distressing sensation. And doing an interview like this—the music-focused part of it anyway—is like opening up an old, usually locked, cupboard at someone else’s request. Full of evocative smells, decaying silks and ghosts.

What’s your view on where the objectification and sexualization of women artists stands today?

I think you’re expecting a highly-informed answer from me, and I can’t give you one, mainly because listening to music is emotionally and often physically painful for me, so I don’t keep up with it. But I will say I’m in the radical feminist camp that believes that even the exploitation of sexuality as a choice made by the individual artist, cannot be divorced from the cultural context in which she finds herself. Not in the way she’s being influenced and not in the way her decision influences her audiences’ view of women in general, either. I realize that race plays into the question to skew it, at which point I’m willing to bow to those who know better than me about restrictions and expectations placed on Black women. But the “pornification” of female artists in general is sickening. It’s one more way of denying our talents and reducing us to our bodies alone. One more way of making us objects and denying that we have minds and souls in a field where both might otherwise have shone. And I think that’s precisely the reason it’s happened.

We’re at an interesting point in history for women’s rights. We’re experiencing a huge backlash on several fronts, from abortion rights to social media and revenge porn, probably not surprisingly around 50 years after the pill and abortion rights became freely available even to single women. In other words, the social ramifications of women controlling their own fertility are finally unmistakably visible. It is no longer inevitable that sexually-active women will have children, nor that the married ones will have a child almost every year, as it was 100 years ago. Women are defining themselves in other ways.

Some pre-historians think that ancient women had the means to control their fertility, but this means that was either forgotten or banned and suppressed or both around the time we began to engage in agriculture. The reasons for this probably included the fact that with agriculture, you can reliably sustain larger populations, but also that there was a fundamental psychological shift in relationship to fecundity and femininity around this time.

The attitude of humans being “guests of” Mother Earth, became “having dominion over” her, echoed in the Eve story and others in the Bible. Generally, we don’t think about it, but most farm animals are female. Chickens, cows and even sheep. So, in order to engage in agriculture you’ve got to be comfortable with controlling female fecundity and feeling entitled to do it. From there, treating your women like breeding animals and controlling the circumstances in which they either breed or not, is a small step. This isn’t a new theory. All the radical feminists will be nodding here, and it’s why many radical feminists are vegan.

Fast forward to now, and we have two generations or more of women who’ve grown up being able to control their fertility and have the power to define themselves in ways other than that of biological destiny. These women are now almost past menopause and are approaching “cronehood”—the most maligned, invisible and potentially powerful part of their lives. That is a profound cultural shift and I’m not surprised our culture is running scared from the power and vision of women who are not chained to inevitable and multiple pregnancies.

ABoneCroneDrone photo shoot, 1991 | Photo: Aditya Bhattacharya

ABoneCroneDrone photo shoot, 1991 | Photo: Aditya Bhattacharya

Tell me about the musical shift you were able to embrace once you broke free from Monsoon and began recording under your own name.

Monsoon was signed to a major label and was expected to release singles and sell as many records as possible. I knew that’s what majors were concerned with, so when I went solo, I deliberately used Steve Coe’s label Indipop as a place that I could retain control and where I wouldn’t have to release singles. It was partly because Phonogram’s heavy-handed manner had disgusted me, but also because I genuinely wanted to explore Asian Fusion and I knew it wouldn’t really be possible to the same extent anywhere else.

But I also had a huge amount to learn. Making a shift from band singer to solo artist at 18 means you’re running to catch up. With my first solo album Out on My Own, the sound was a lot like Monsoon, though less expensive, obviously. But behind the scenes I was learning really fast about how the studio process worked, as we were early adopters of the 8-track home studio to make my first four albums. And I made the leap into songwriting at 19 with my second solo album Quiet. That was really where my solo career, and the consequent vocal exploration really began. That was when I started to think of my voice as an instrument and started to break out of the songwriting boxes singers are usually put in.

And it wasn’t easy, emotionally. At 19, you still have that instinct to conform. You want to be like your peers. Your worst fear is that you’ll reveal what’s really within you and that people will hate it or think you’re weird. No Asian teenagers I knew had an artist vision like mine. But as an artist, that’s exactly the fear you need to conquer. In fact, it’s the conquering of that fear that non-artists secretly admire you for.

In short, I think of those first four solo albums like artist sketch pads. A bit hurried, with the odd horrible mistake. But absolutely necessary for my development.

What did your Real World period enable you to explore that you weren’t able to previously?

I knew someone who’d already approached Real World, so I knew what kinds of advances and terms they were offering in the early ‘90s. I made it a condition of licencing Weaving My Ancestors’ Voices that we had one of their studios for five days as part of the advance to my production company Moonsung, in order to mix the album. So, I knew we could work to a high technical standard, which I hadn’t had the money to do with my previous five solo albums. Steve Coe and I also knew much more from making those early Indipop albums about how my voice should be treated. I don’t think spending 16 hours treating a single vocal line and setting the new industry-wide technical standard those albums set at the time, would have been possible otherwise. I also wanted to make the standard of writing match the high technical standard. So, with the exception of AboneCroneDrone, which couldn’t have been written any other way, we spent about 10 months crafting each of those Real World albums before we went into the studio to record. That’s why they’re the best songs and the best performances of my career.

The Zen Kiss photo shoot, 1994 | Photo: Sheila Rock

The Zen Kiss photo shoot, 1994 | Photo: Sheila Rock

Was it a relief to be entirely decoupled from the world of pop at that point?

It was and it wasn’t. After Weaving My Ancestors’ Voices, I still had record executives and marketing teams everywhere I did press with Virgin beg me not to do another solo voice and drone album. They still wanted Monsoon mark two. I didn’t want to play the pop singles game as it cost so much, that no company was going to let me do that and make the music I wanted to. I like pop as much as anyone. I really wanted to be a soul singer as a teenager, but at that point, pop wasn’t really a viable choice for me.

I also knew my value as an artist. I’ve never been the artist a label signs because they want to sell squillions of records. I’m the one they sign because they want to increase their kudos. I think Real World signed me on that basis. They certainly didn’t expect a solo voice and drone album to sell. And also because at that time they had lots of African artists and lots of male artists. I took one look at their catalog and thought “What you need is an Asian woman.” And you need an artist that is perceived to make not “Saturday night” songs or traditional classical or folk, but something original, that in musical terms is more like high art. And having one that lives down the road—at that time Real World tended to record artists from other countries that were touring with WOMAD—so that she’s around to do some promotion when the time comes, would be no bad thing either.

I only recently became aware of the 1992 car accident that resulted in the operation that damaged your voice. Tell me about that and how you persevered to continue your music career with Real World after that point.

Well, it was a scary time because I nearly lost my sight. I had detached retinas, and needed emergency surgery, and the recovery was no picnic either. I wasn’t in pain, but I could hardly see, had to lie down on one side for two weeks so that my eyes could heal, and had to adjust to distorted and double vision resulting from the change in the shape of my eyeball due to the plastic buckle they put around my right eye to keep it together, which is still in place. At first, I needed double prisms in heavy glasses, because of what the buckle was doing to my vision. But I knew I couldn’t sing in glasses like that, with so much weight on the bridge of my nose, and had to train my eyes to refocus over a period of months.

With all that going on, I didn’t notice what was happening to my voice at first. It slowly lost agility and power and became strained in the sense of a literal strain to the muscles in my larynx. What I only found out years later, was that during the operation while being intubated, the anesthetist had nicked one of my vocal chords, which then healed with inflexible scar tissue. The damage is small, but enough to ensure that my vocal chords don’t meet in the middle as they should, which means that on one side the muscles have to work harder and get sprained with each use.

After a while, I could no longer pitch properly. It was very scary. My sinuses were also playing up, but an operation to clear them and remove excess bone in 1998 helped. After that, I went to remedial singing teachers, but none of them was ever able to restore my voice fully, due to my physical limitations.

I did manage to give concerts, but I could never again write effectively on my voice, which is why ABoneCroneDrone has minimal voice parts and This Sentence Is True is more of a studio collage creation and a Ganges Orchestra project. And singing constantly on a painful voice may have primed my whole system for pain. It wasn’t good for my mental health to spend whole summers without social contact so that I could rehearse and sing either. Anyway, one of the nerve specialists I saw post-2010 thinks that the chronic throat pain caused my BMS, because too much throat pain set the nerves in my mouth off and made them oversensitive.

This Sentence Is True photo shoot, 2001 | Photo: Jo Swan

This Sentence Is True photo shoot, 2001 | Photo: Jo Swan

Tell me about the musical shift that occurred for you in 2000 when you created This Sentence Is True and the two EEPs.

I really didn’t have that much to do with the making of the two EEPs. Steve Coe said he wanted to go into the studio with a Ganges Orchestra project and would I do a vocal session. We knew my voice was bad and that I couldn’t manage any more than three hours. So, we got together a list full of strange and unusual vocal sounds, not that much in the way of melodies, and I recorded them all in one go. Steve would go off and play around with them and he slowly built up the tracks for the EEPs.

At the same time, I had rashly promised my next album to Real World and I think they were rather counting on me delivering one. They never found out because I didn’t want to make excuses for myself, but I spent months in pain trying incredibly hard to write on a voice that wouldn’t cooperate—so much so that I made myself ill. That’s when I had to stop and admit defeat.

Steve had been crafting first the two EEPs and then This Sentence Is True, but I really hadn’t had much input. I wasn’t at the mix sessions and wasn’t taking it terribly seriously, partly because I was busy with the album which never came off for Real World. When Steve decided to license This Sentence Is True directly to Narada, who at that point were Real World’s US licensees, Real World was very unimpressed and I can’t say I blame them. Steve had a direct relationship with Narada, because he’d signed my Indipop back catalogue directly to them, so it was logical, and he also thought my negotiations with Real World quite tortuous and was loath to engage because of that, but it must have looked as though I’d deliberately “thrown up” doing an album for Real World to aid Steve, which was never the case. I’m still not sure they’ve forgiven me.

Reflect on the passing of Steve Coe in 2013 and your working relationship as you created music together.

Steve was an experienced writer and producer of 14 years standing when I met him at 16. He helped me learn about my role, as he learned from others when he started out. We worked very closely together over a long period and he had a great influence on my work. But still, I’m going to ask you to work a little bit harder as you read the following. I’m going to ask that you continually consider the power relationship you assume when thinking of two long-time collaborators who are not of opposite genders and different races, like say, Elton John and Bernie Taupin. Just because their careers are closely intertwined, do you assume the same things about worth, power and possibly dependence about each of them as you do about Steve and I?

Would I have entered the field of Asian Fusion without Steve? No way! Would I have gone solo at 18? Well, Phonogram pushed me into that, because the only way to get out of the Monsoon contract with them was to go solo. The idea for my first big change of direction as a solo artist with Quiet, a lyric-less series of 10 tracks featuring over-layered voice as an instrument, was mine. On the other hand, I wasn’t a writer beforehand and Steve gave me the confidence to co-write it, which as the vocalist, was crucial. He also helped me develop many of the self-management techniques you need to stay sane as an artist who works alone for months on end.

The idea of doing a solo voice and drone album as an accompaniment to my first concerts, Weaving My Ancestors’ Voices, was Steve’s idea. They idea of crossing continents vocally within a single melodic line, and indeed the technique breakthroughs, so that I could, were mine. Weaving would have been a totally different album otherwise. The idea to write a vocal percussion piece called “Speaking In Tongues,” which eventually grew into four pieces, was Steve’s. However, spending eight months rehearsing vocal percussion patterns like some mad muttering old lady before I could come up with close to the final form of, for instance, “Speaking in Tongues III and IV,” was all on me.

Did he influence me? Yes. He was fabulous with running orders—just incredible—which is an essential skill when presenting challenging work to your listener. And he was a highly-detailed and accomplished producer. I know the buzz ‘round the industry was that the Real World trilogy set a new standard in vocal production in the industry in the ‘90s. Producers had simply never heard a naked voice that had had 16 hours of production time lavished on it. AboneCroneDrone was my idea, but I’d never have been able to execute it in a month of Sundays. In fact, when it was reissued recently in Spain, they wanted to remaster and I wouldn’t let them touch it, because Steve wasn’t there to oversee the aural tricks he built into it as a producer, and I didn’t know how he’d done it. Remastering it would have ruined it. He was also great at thinking of musical premises that were totally out of the box and was completely unfazed by the notion of what was cool and what wasn’t.