Donate to Innerviews

Since 1994, Innerviews has provided uncompromising, in-depth interviews with musicians across every genre imaginable. And it does that with no trackers, cookies, clickbait, or advertising.

Your donations are welcome to help continue its mission of highlighting incredible music and artists, without any commercial considerations.

Your contributions will be instantly transformed into stories and videos, and cover hosting and web management costs. Importantly, your dollars will help ensure Innerviews remains absolutely free to all visitors, independent of their ability to financially support it.

Please consider making a donation today by using the PayPal QR code below.

The Northern Pikes

Forward Momentum

by Anil Prasad

Copyright © 2018 Anil Prasad.

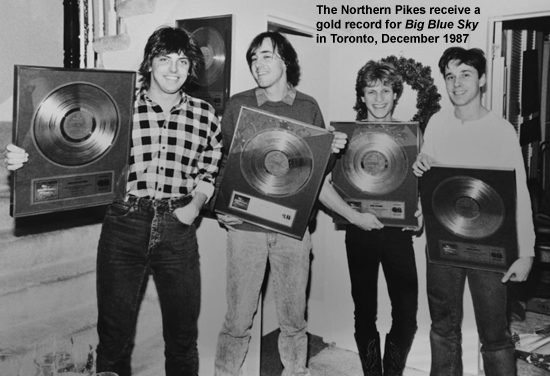

Simply put, The Northern Pikes are a Canadian institution. The band’s songs are forever part of the country’s collective ‘80s and ‘90s soundtrack. During its years signed to Virgin Records between 1987 and 1993, the group had one double-platinum and four gold albums, and eight hit singles that remain mainstays in Canadian radio playlists.

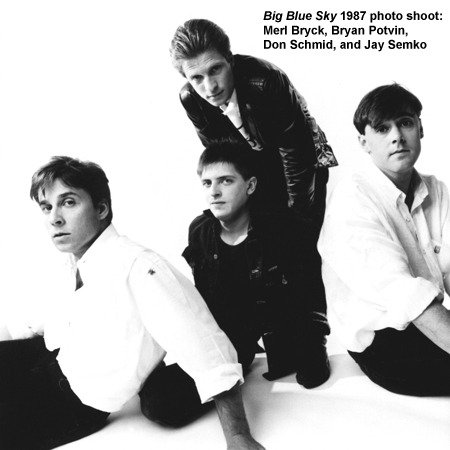

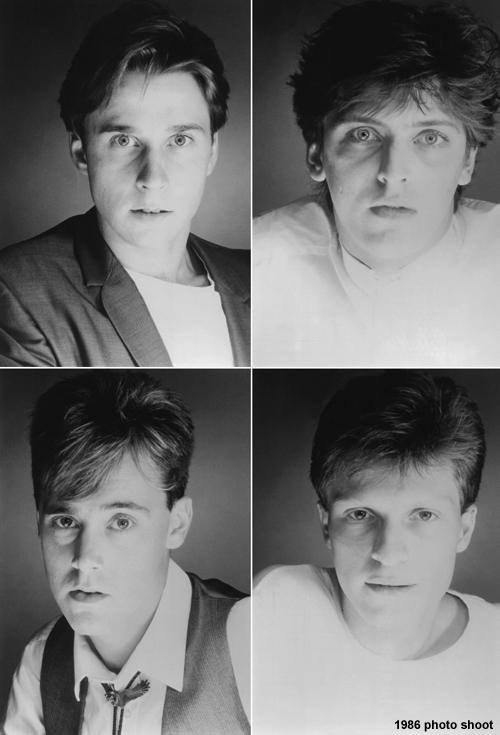

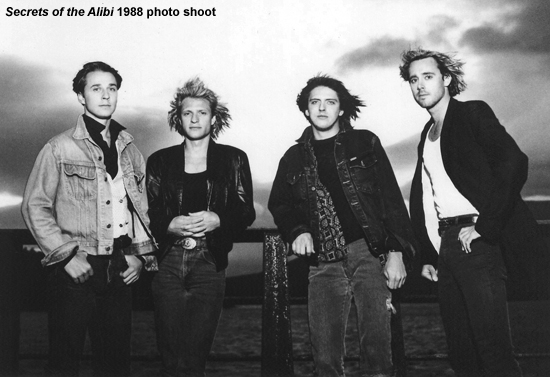

The group was formed in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan in 1984. Its core lineup of vocalist and bassist Jay Semko, vocalist and lead guitarist Bryan Potvin, vocalist and rhythm guitarist Merl Bryck, and drummer Don Schmid remained intact from 1986 through 1993, at which point it broke up with members pursuing solo projects. It reunited in 1999 and has remained a recording and touring unit ever since.

The Pikes, as they’re affectionately known, were always determined to serve the song during the creative process. The band’s output combines strong vocal harmonies, pulsing basslines, guitar approaches that morph from lush and spacious to distorted and processed, and kinetic drumming. They managed the rare feat of merging the accessible and the adventurous. The combination proved irresistable for Canadian youth, who ensured Pikes singles such as “Teenland,” “Hopes Go Astray,” “She Ain’t Pretty,” and “Girl With a Problem” became staples on Canadian radio and MuchMusic, the country’s first music video channel.

The band celebrated the 30th anniversary of its Virgin debut Big Blue Sky in late 2017 with a major, cross-country, 29-date tour. It was in support of a deluxe edition of the album titled Big Blue Sky (Super-Sized). The expanded release, issued as a triple-vinyl gatefold and double CD, includes 10 previously-unreleased demo tracks and a 1986 live recording of the band at Toronto’s Horseshoe Tavern.

After Bryck retired from the music industry in 2006, the group performed as a power trio with Semko, Potvin and Schmid. But for the Big Blue Sky 30th anniversary tour, The Pikes chose to augment the band with vocalist and guitarist Kevin Kane as a full-time fourth member. He’s best known as the co-founder of The Grapes of Wrath, another highly-successful Canadian band.

Prior to joining The Pikes, Kane struck up a songwriting and performing partnership with Potvin known as Kane & Potvin, which released a self-titled album in 2016. The success and chemistry of the duo led to the Pikes invitation.

“I was quite familiar with the popular stuff through MuchMusic and radio,” said Kane. “Once I started learning the songs on their set list, I was pretty happy that their catalog ran so deep with so many good tunes, and they're really fun to play. I know that we in The Grapes of Wrath always felt a strong affinity with The Pikes because both bands were from smaller cities in Western Canada—us from Kelowna, British Columbia and them from Saskatoon, and we both put the emphasis on songwriting, melody and harmony.”

The 2017 tour was an affirming experience that solidified the new lineup as an ongoing concern.

“It was one of the best tours I've ever been on—a best-case scenario on every level,” said Kane. “The songs are all really strong. Musically, they gave me a fair bit of free reign on deciding on where to replicate guitar parts or harmonies and where to come up with my own approach.”

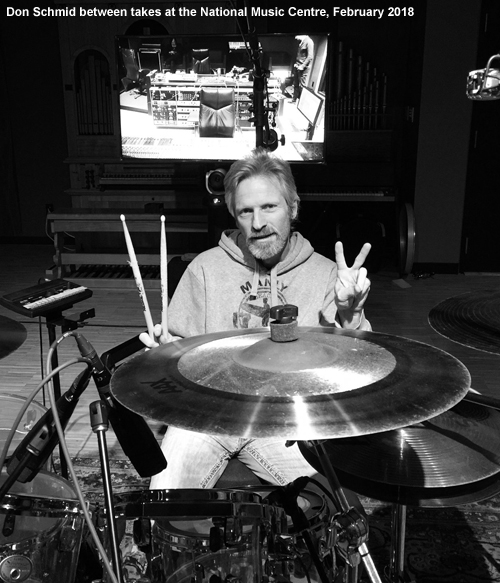

In fact, the band was so pleased with the how the new quartet coalesced that it chose to enter the studio last February to work on its first album in 15 years. It decamped to Calgary’s National Music Centre’s studio facilities for 10 days.

“We got seven songs tracked, which is the fastest any of us have worked since back in the mid-‘80s, so there was a real energy to the sessions,” said Kane. “The stuff we've done so far runs the gamut from folky to pretty aggressive. No-one in the band gets precious about their parts. Everyone listens to everyone else's ideas and is always willing to try things out. They even encouraged me to have a go with the Wurlitzers and Mellotrons at the studio.”

Innerviews spoke to Semko, Potvin and Schmid about the band’s past, present and ever-evolving future, as well as their solo careers.

Jay Semko

What’s your view on the value of music and its ability to connect people in these challenging times?

Yes, the world is kind of crazy right now. But maybe we’re just so much more aware of it in that we’re so connected now. Music and the arts are the most unifying forces we have as humans. There’s a universal language that music represents.

I’m a huge fan of the arts in general. I don’t like it when arts funding gets cut. It’s always a battle. Music in schools is so important and life changing. I’ve witnessed it for myself when I’ve gone to play music for kids in schools. It’s so fun because they’re like sponges and just pick it up. When I do my solo acoustic shows for kids, I try to shame the adults into singing along. [laughs] My love of music has not faltered. In fact, I think I appreciate it more than ever now.

A few months ago, I saw k.d. lang perform during her Ingénue Redux tour. I was there with my fiancé and it just took us somewhere else for a couple of hours. I thought “Wow, I can’t remember having an experience like that for a while.” So, when we approached the idea of the Big Blue Sky 30th anniversary tour, we wanted to put ourselves in that zone. We wanted to go somewhere else for two-and-a-half-hours and take the audience along with us. We didn’t want to have any distractions. People were supposed to put away their phones and connect with live music in the moment. Nothing beats that.

Describe how the Big Blue Sky (Super-Sized) edition and 30th anniversary tour came together.

We first talked about doing a 30th anniversary edition of Big Blue Sky in 2016, a year before it came out. We had been in touch with Universal Music, who now own the Virgin catalog, in 2015 because they did a best-of Pikes compilation as part of their Icon series at the time. So, when the time came for this project, we were able to have some good, honest discussions. They wanted to know if we were planning on touring it and we said yes.

It’s interesting because Big Blue Sky is not our biggest-selling album. Snow in June, our third album is. But Big Blue Sky left a huge impact on a lot of people. I didn’t really realize it until we went out and did the tour. People talked to us after the show and told us the album meant so much to them. They told us about major life events that were happening when the album came out or how it related to meeting their husband or wife. Other people told us it reminded them of being in high school. It was somewhat shocking for us to realize how many people had these stories. They’d often also talk about the two videos from the record for “Teenland” and “Things I Do for Money.” I was pleasantly surprised to see how far-reaching the music from the album has been.

The Big Blue Sky (Super-Sized) edition was fun to assemble. We went back and listened to a lot of the old recordings we did that pre-dated the band signing to Virgin. That’s where the unreleased music on the reissue comes from. There was a ton to choose from. It was a case of finding the stuff that works well in a cohesive manner, and audio-wise was palatable to listen to. Peter Moore did a great job cleaning up the tapes. Some of the tapes had to be baked. There were no new recordings or mixing done.

Don Schmid has always been a great archivist for the band, right from when he started with us in mid-1986. He had a treasure trove of these early recordings that he kept and organized. As we went into the project, I realized there was still more stuff to discover. Some of it was stashed in my parents’ house in the basement. The recordings also made me go “Wow, I can’t believe I’ve been doing this for so long.” It seems like a long time ago when Big Blue Sky was done, but when I started listening to it and the unreleased music, lots of memories and good things started to happen.

You demoed nearly 100 songs for Big Blue Sky before recording the album. Tell me about the process of recording those and choosing the music that ended up on the album.

Some of them were quick, live off-the-floor recordings we did at Studio West, with our buddy Mitch Barnett engineering. Some of them we spent a little more time on, with overdubs, but they were still basically demos. I’m hoping there will be future reissues of our later albums, because there are lots more demos. The quality goes from quite good to the point where the demos were actively competing with the album recordings. We got better in the studio and in terms of engineering. We were able to create some pretty cool stuff during the demo stage. One of the Big Blue Sky demos, “Do You Really Want Me?” was used as a b-side for “Let's Pretend,” a single from Secrets of the Alibi.

Despite demoing so many songs, half of Big Blue Sky featured re-recordings of material from your prior two independent releases.

It came down to the familiarity factor. The label looked at the stuff that had been on the independent self-titled EP and Scene in North America LP and thought “Well, these work pretty good. Let’s enhance them and re-record them.” Our independent recordings got some airplay, including songs like “Teenland” and “Lonely House.” “Things I Do for Money” and “Big Blue Sky” were demoed in the early days, but weren’t on the independent records. It’s funny that when I wrote “Things I Do for Money” and presented it to the band, I felt it was quite a bit different and a lot darker compared to anything else we were doing at the time. I wondered if it was a song the Northern Pikes should do. But the band loved it. Bryan immediately picked up on the vibe and came up with the delayed-guitar parts.

Something similar happened with “She Ain’t Pretty” years later for Snow in June. Bryan Potvin was writing a lot more and we would exchange cassettes of acoustic recordings of our songs. He gave me that one as part of a series of five or six songs. I heard it and thought “This is a fun rock and roll song.” He said “Oh no, it’s a silly song.” And interestingly, “Things I Do for Money” and “She Ain’t Pretty” ended up as two of the most well-liked songs in the whole catalog. They were both songs we felt were too different for the band. Ultimately, they ended up being songs that lasted a really long time. At the end of the day, a good song is a good song. You just have to give it to the band, let everyone work out their parts, and let it be what it is.

How much involvement did Virgin have in Big Blue Sky?

Doug Chappell, the president of Virgin at the time, is pretty cool. He’s a true music lover. It was good to have somebody giving us a little bit of direction in terms of what they liked. I never felt like we were controlled or manipulated. It was always an open conversation. If you’ve got something good, you just know in your gut that it’s the case. We all related to that idea, including Doug. At the time of Big Blue Sky, it was tough for me sometimes, because I was the primary songwriter then. Your songs are your babies and you get attached to them. That’s why it was nice to have producers like Rick Hutt and Fraser Hill provide input. Rick was a really good arrangement guy. He could really cut to the chase and hit the right arrangements.

Over time, I got better at self-editing my songs. But for many years, I tended—as many writers do—to make the songs a little long. Sometimes the arrangements weren’t quite there. The great thing about being in a band like the Pikes is you had three other critics or quality control people to tell you what they think. If you’re in a band for the long haul and know each other well, you’ll respect one another’s opinions.

I read Glyn Johns’ autobiography Sound Man recently, which is a great book. He produced the first Led Zeppelin record. He loved the band and was trying to turn people on to it, but some people just weren’t getting it back then. He couldn’t even get Mick Jagger or George Harrison to get it. It didn’t really matter, ultimately. Zeppelin went on to become one of the biggest bands ever. But it was interesting how Zeppelin didn’t really do it for some other musicians. So, when it comes down to presenting songs to others, sometimes some people get them and other times they don’t. Doug heard things in our songs we didn’t hear sometimes. He would say things like “I’m really interested in hearing what you guys can come up with in terms of different sounds or vocal arrangements.”

The band’s songs going back to Big Blue Sky have always had unique arrangements, full of interesting twists and turns. Where did that instinct come from?

We always liked being outside the norm. When things got too standard, we’d always go “No, no, no, we’re not going to do this.” I remember doing different versions of songs along the way and thinking “I like what the song was like when it was quirkier and stranger.” Rick and Fraser had something to do with some of the interesting quirkiness on Big Blue Sky. With Rick, it was never over until it was over when it came down to a particular guitar sound or drum roll where you wouldn’t expect it. He would often be the guy who would throw that out there.

How did the group’s creative process work back then and how did it shift as Potvin evolved into being part of the band’s songwriting mix?

With Big Blue Sky, some of the songs were ones we played for quite a while, long before we signed a record deal. It was me giving the songs to the guys and having them come up with their thoughts on them. I would usually sit with Merl and work out some vocal harmonies if there were songs that lent themselves to that. It went from there to Bryan adding his colorations with the guitar, and then Donny coming up with his drum parts. It was pretty organic, really. We kept things fairly open. We ultimately trust each other, musically. We work things out, jam on them and play them. We always arrive at a certain point where we realize we’re either getting there in a song or that the song isn’t going to happen.

These days, Bryan tends to bring in elaborate demo recordings using a drum machine. I always keep things really basic, with just voice and guitar or piano on demos. Then I’ll give it to the guys and see what they want to do with it. Sometimes I have a really specific idea of what I want the song to be and sometimes I don’t.

“Things I Do for Money” and “Big Blue Sky” are very deep songs for someone in their early twenties to write. Describe the origins of those tunes.

When I first started writing songs, I would often try to sound like somebody else. I got to a point where I was really frustrated and realized I didn’t like that approach. I almost quit writing songs before figuring out you gotta write what you know. I decided to write about things that were actually happening in my own life and things I was observing. I basically became myself within the songs and that took a while to achieve. It took a lot of trial and error, and work. I continue working on that today.

“Things I Do for Money” was a song I literally wrote in about a half-hour. The lyrics were written as I was watching late-night TV. I just started writing free-form thoughts down and came back to them the next day and thought “Well, this is kind of different. Is this a song? There aren’t really any rhymes in it. There’s a stream-of-consciousness thing going on here.” I came up with the idea of the repeating element at the beginning, which eventually became a version of what Bryan ended up doing on his guitar.

Some people have said “Things I Do for Money” sounds world weary or wise beyond my years, but I felt it was just a song. It was just the way it happened. I don’t exactly know where songs come from. Sometimes they just show up. One thing I’ve fought for many years is the fact that songs often happen at inopportune times. I have to write it down or do a quick recording of it so I can capture the idea. These days, I record ideas on my phone. I have all these bits and pieces of musical ideas and lyrical thoughts on my phone.

“Big Blue Sky” was probably the last song that was written before we recorded the album. We did a quick demo recording which wasn’t all that different from the final track. It was a little more raw and a bit faster. I can remember looking at the songs we had already put together for the album and thinking “There are some pretty dark things going on here. You need to have something a little happier on the record too.”

I think I was driving down the highway when I came up with the song. The stuff about my brother in the song is all true. I never won a trophy. I never had one. And he had lots of them. He was a great athlete. Those were thoughts that were crossing my mind at the time. There wasn’t a lot of editing needed. I had other songs at the time that I had to spend many hours and weeks on, but both “Big Blue Sky” and “Things I Do for Money” happened pretty quickly and organically. They weren’t overthought in any way.

The album version of “Big Blue Sky” features Wendy Davis singing the high vocal parts while I play acoustic guitar. It was an idea that Rick Fraser had. He said “You need to Prairie this up.” [laughs] We needed something to bookend the album. “Teenland” was the first track and “Big Blue Sky” worked really well as the closer.

We had the multiple vocal thing going on in “Big Blue Sky” and it was really fun to go out on the Big Blue Sky 30th anniversary tour and play that song using three-part harmony again. We haven’t been able to have three vocal parts for a number of years since Merl stopped playing with the group.

Why did Bryck choose to leave the band and retire from music?

To be fairly blunt about it, when we started playing again in 1999, Merl’s heart just wasn’t in it to the extent everyone else’s was. He did it because he’s a friend and he has a true love of the band and the music. But it just got to the point where I could tell he really wasn’t going to play with us anymore. This is something you really want to have to do, especially when you get older. It’s not something you’re going to make a lot of money doing. You really have to have a passion for it. I felt Merl didn’t have it when he started playing with us again. The same desire the rest of us had wasn’t there. It’s not that he loves music any less. He’s still a big music fan and we’re still pals. We still communicate regularly, but I think he looks at the band as something he used to do.

Back in 2006, we were offered a New Year’s Eve gig and Merl didn’t want to do it, and the rest of us did, so we went out and played as a trio. There was a lot of that—Merl not wanting to do things. So, we got to the point where we said “Okay, we’ll do this without you, because we still like playing.” The door was left open for many years for him to come back, but he never really wanted to.

Today, Merl works for the city of Saskatoon as an assistant groundskeeper at a golf course during the summer. During the winter, he manages one of the public hockey rinks. In the video for “Underwater,” you’ll see Merl driving this big Zamboni at Archibald Rink in Saskatoon. He’s been doing that since the mid-‘90s and he enjoys his work and life there. Life goes on and people change their minds about things.

Describe how Kevin Kane became involved in The Pikes.

We had been playing as a trio for the last seven years. Merl hasn’t been involved since 2006. Once he stopped playing with us, we had Ross Nykiforuk step in as a keyboardist. He was our hired gun and unofficial fifth guy for the Snow in June and Neptune tours. There were some dates he couldn’t do in 2010, so we played them as a trio and they worked pretty good. We stuck it out as a trio for a while. But for the Big Blue Sky tour, we wanted to have a fourth person on stage with us. Kevin from The Grapes of Wrath came to mind. He had been playing with Bryan as Kane & Potvin for a couple of years. They also did a record together and have also toured.

So, we did a couple of experimental gigs last summer. One was at Seneca Queen Theater in Niagara Falls and the other was a Canada Day gig in Barrie, Ontario. It sounded great. We all thought it was a natural fit. So, for the Big Blue Sky 30th anniversary tour, we brought him along. We did some rehearsals at Bryan’s place in Nova Scotia for a week. Then the crew came out and assembled the videos that ran behind us for the show. We had a rehearsal night in Saint John’s, New Brunswick at the beautiful Imperial Theatre with the full production. The next night was the official first gig of the tour and away we went. Kevin is great and it’s worked out well. He’s a great guitarist and singer. I’ve been a huge fan of The Grapes of Wrath right since their early days when they did an album called September Bowl of Green.

There’s a lot of discussion in the liner notes of Big Blue Sky (Super-Sized) about The Idols, the band that preceded The Pikes. Trace the journey of that group for me.

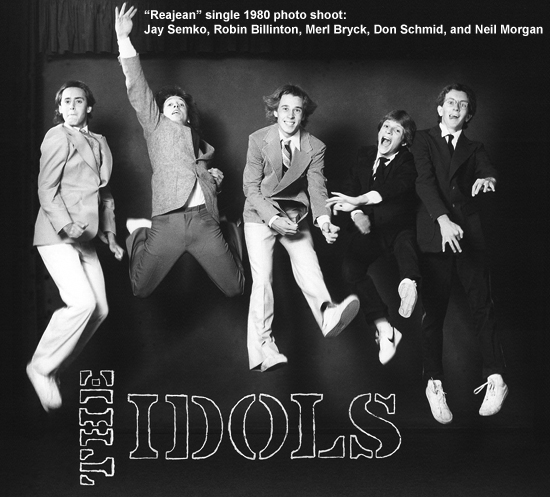

The Idols were a band that formed in 1979. The original people in the band were Merl and myself. We started out as a New Wave cover band and played a lot of stuff from the era by The Police, Squeeze, Graham Parker, and The Sex Pistols. I first really started writing songs in The Idols. There were a number of different versions of the band that got together and broke up. The final lineup of the band was myself, Neil Morgan and Merl on guitar and vocals, and Don Schmid on drums. So, three of the future Pikes were in the group.

The first time I saw Bryan Potvin play was at a New Year’s Eve gig we did. He was in a band called Doris Daye. They opened for us. Bryan impressed me as a guitar player. I was in another band at that time called 17 Envelope. I had left The Idols in 1982. What ended up happening was I did a lot of writing. I spent a lot of time with Merl, Neil and Don. We all became very good friends. Neil ended up joining a touring cover band called Dear Friends. To make a long story short, in January 1984, Dear Friends were in a car accident and three members were killed, including Neil. It was near Brooks, Alberta. I think a semi-truck jack-knifed in front of them.

Neil’s passing was very tragic. He had just gotten married. He had a baby. It was a horrible, horrible thing. Neil was a really good songwriter and he influenced me in terms of the competitiveness between him, Merl and myself. It was a friendly thing. He was also one of the smartest guys I ever knew. We would play the Elvis Costello song “Less Than Zero” and Neil would change the lyrics every night to some current event that happened that day he heard on the news. It was an almost off-the-cuff thing. He could do things like that. Every night it would have a different set of lyrics. It was mind-blowing how quickly he was able to come up with those kinds of things. He was a really good friend.

I had been talking with Bryan about forming a new band a few months before Neil died. After that happened, Merl, Bryan and I said “You know what? Let’s do it.” Neil’s passing was a life-changer. We realized how quickly things can change and how much we love music. We really wanted to do this and have a band. Neil’s death in some ways was the catalyst for us to really start revving up and getting The Northern Pikes started. Within a month of Neil’s death, we were rehearsing and getting it together. The seeds of The Pikes were from that tragedy. When Neil died, it was a reality check. It was time to commit to doing this new band. We dedicated Big Blue Sky to the memory of Neil.

The Idols recorded a 7” single in 1980 titled “Reajean” with “I've Been Inside” as the b-side. What do you recall about the making of it?

“Reajean” is kind of an interesting song. Merl wrote that. My family had a dog named Regent, so he took Regent’s name and created this other name Reajean as a girl’s name. We recorded it at Eagle Creek Recording in Rosetown, Saskatchewan, about an hour outside of Saskatoon. The guy who ran it basically had a recording studio in a trailer in his backyard. It was a semi-professional studio. We did the two songs in one day. It was made by the version of The Idols that included me, Merl, Don, Neil, and Robin Billinton on guitar.

“I’ve Been Inside” is a really cringeworthy song. I think “Oh my gosh” when I hear it. [laughs] It was the early days of songwriting for me. It’s just a cheesy song in my opinion. The melody was okay. “Reajean” I quite like, though. A local rock radio station would play it and it was a big thrill for us to hear one of our songs on the radio. We made a few hundred of the singles.

In the Big Blue Sky (Super-Sized) liner notes you said you were hospitalized for severe depression in 1983. What was going on?

Depression is something I’ve dealt with for most of my adult life. I was very depressed and suicidal at that time. In August 1983, I ended up in the hospital. I had gone through a relationship breakup. I was doing a lot of drugs and drinking a lot. I had quit the band 17 Envelope. It was a train wreck of my own making. My doctor got me into City Hospital and I spent a month there. I was on different medications, including lithium, which I was kind of overdosing on. They were giving me way too much, so I was hallucinating. So, they took me off that and put me on an anti-psychotic drug. After a month, I thought I didn’t feel so bad and thought it was time to get back into the world, so I did. But a few weeks after I got home, I had to have wrist surgery. That turned out to be a lot more of a hassle than I thought it would be.

I couldn’t play the guitar for months or work on anything else. So, I attended the University of Saskatchewan in Saskatoon, where I studied arts and sciences, majoring in Political Science. I encountered Bryan at the university, where he was doing a first-year general arts and sciences degree. He was there at the same time, kind of going back to school in lieu of other things that were going on. So, we ran into each other, went down to the pub and spent a good portion of the day there. We hatched our plans for a new band and that’s how The Pikes got going.

How are you doing today in terms of managing depression?

I’m doing all right with it. I was on an anti-depressant for a number of years and got off it a few years ago. I just have to be aware of it. During the Big Blue Sky 30th anniversary tour, we had a CAMH Foundation booth set up by our merchandise stand. They were at every show. CAMH stands for the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health. During the first set of the show, I would talk a little bit about them and how I have struggled with depression. CAMH saves lives.

We felt like we were raising awareness and helping to lessen the stigma about mental illness that is a reality in many people’s lives. I had to deal with it for a number of years. I’m an addict. I have an addictive personality and it doesn’t matter what it is. It’s even true for exercise. I chose to stop drinking and using drugs. I still love to eat junk food. [laughs]

As the Frank Sinatra song goes, it’s “All or nothing at all.” But you can use that in positive ways. I know where I’m at. It’s manageable. I have to do a self-check every now and then. I might decide I need to take a look at stuff and change things a little bit, but for the most part, things are going pretty good.

The Big Blue Sky 30th anniversary tour was tough because my mother was very ill. She was in palliative care in Saskatoon for the duration of the tour. I came back a couple of times and had some good visits with her. But she passed away literally the night before the last show of the tour. That last show was a challenge, but I focused and got through it. It was a tough time, going back and forth between the tour and seeing her. My mother was conscious and alert until the last few days. She had a good attitude about everything and the big picture. She had a good sense of humor about it. She was very courageous and I learned from that.

Describe the progression from the first two Pikes independent releases to getting signed by Virgin for Big Blue Sky.

We were very isolated back then. I was almost in my twenties before we had cable TV in Saskatoon and more than one channel. There was a show on that would air on the local FM rock station between midnight and 12:15 am from the BBC that would tell us what was going on in the British scene. We were totally glued to that. That’s how we learned about new music, in addition to the local Records on Wheels store.

There was a cover band circuit that existed and we would go out and play six nights a week at clubs. These bars were pretty popular. We decided we would play that circuit and throw in some of our own stuff and make some money. We were able to be working musicians, put money in the bank and finance a recording. Most other bands didn’t do that. They would put their money into lighting or update their sound system. Almost everyone traveled with their own sound systems back then, but we didn’t. We rented the bare minimum we needed to do the gigs. The less we spent, the further ahead we would be to make a recording.

When we finished the first EP, we pressed 1,000 copies initially and did another 1,000 later. We sent them to agents, producers, management companies and radio stations—especially college and independent stations. There really wasn’t a way to find a lot of these addresses back then. So, I did a lot of letter writing. I wrote a letter to the Library of Congress in Washington, DC and they send me back a list of college radio stations in the US. We put packages together ourselves and Robert Hodgins, who was a local booking agent in Saskatoon, had the great idea of having us include a self-addressed, stamped comment card that people could fill out and send back to us to tell us if they were playing it or not. Many of them responded and started sending back charts and playlists that included us. It was amazing to us. Learning there was a station in South Carolina or Nova Scotia that was playing us was a cool thing and encouraging.

When Scene in North America came out in 1985, we were playing our own stuff. All the record labels were very interested in us. We played a gig in Toronto opening for Jeffrey Hatcher at the Horseshoe Tavern and then the next night we did a headline show at a place located kitty corner called The Holiday Tavern. Apparently the whole audience was record label people. We were naïve about that. I’m glad nobody told us or we probably would have been very nervous. But we had a good show and a lot of people were interested in talking to us.

Interestingly, Doug Chappell from Virgin was not at that show. He came out to see us play a showcase-type thing being held by Robert Hodgins’ talent agency. He did a showcase for people to book bands for dances and special events. We were scheduled to do a short 20-25 minute set. Doug flew out to see us play one of these things. He fell in love with the band. He talked with us afterwards and followed us for about a year before finally making us an offer. From there, we started negotiating the Virgin record deal.

What do you make of the fact that since Big Blue Sky came out in 1987 we’ve gone from vinyl to CD to MP3 to streaming and now partially back to vinyl?

It’s interesting how things go full circle. The idea that Big Blue Sky is now a triple-vinyl release is pretty cool. I used to have Sandinista! by The Clash and Rare, Precious & Beautiful by The Bee Gees, which were both triple-vinyl releases. Those are the only ones I can remember owning myself. So, the fact that Universal Music did that for us is great.

I think there’s a real desire for the organic nature of music to reemerge. I know we can easily access music online these days. But when I learned bass parts to songs as a kid, I would sit alone in my bedroom, lifting up the needle and dropping it at a certain part of the song over and over again to learn it. It created a real affection for the music. You became really attached to it in the process.

I have two daughters and they’re both into records. They have record players I gave to them. I also gave them most of my records because they want to play vinyl all the time. I kept a number of albums for myself, too.

There’s still a real desire for people to have something they can hold. That’s a big part of vinyl. The artwork is amazing on LPs. When it came time to release The Pikes’ Neptune album in 1992, I remember that was the first one that wasn’t going to be on vinyl and I was really saddened by that. The cover was cool and it should have been seen bigger.

The other thing about vinyl is people really wanting to listen to music without skipping around. Most people listening to vinyl listen to the entire album. When I grew up in the ‘70s, tracks weren’t considered any more or less important because of where they were in the track order. We looked at albums like books and songs as chapters of the books. I think people want to revisit that.

Even with the reemergence of vinyl, the fact is the majority of people no longer pay for music. How do you address the challenge of earning an income given that reality?

You just have to accept reality. There was a time when the sky was falling, but then live music became a priority again. People still love live music. Bands continue to play. It’s something that can never be duplicated. Every show is going to be a couple of degrees different every night. The vibe of the room, the sound or whatever it is that’s going on changes things. However much you try to recreate the exact same show, you never completely will. I just throw the acoustic guitar in the car and go out and play gigs when The Pikes aren’t touring. I have to be adaptable in that way.

My son, Jackson Semko, is seeing that first-hand, too. He has a band called Caves in which he plays bass and guitar. He was also in another band called Sexy Preacher. On the Big Blue Sky 30th anniversary tour, he was the guitar tech and came out on the road with us. It was good to spend time with him and take him on a bit of an adventure.

As for the challenge of making a living, I have to be diverse. I do voiceover work. I’m a full ACTRA member, which is the Canadian version of the Screen Actors Guild in the US. I also do songwriter workshops. In addition, I’ve been fortunate to have done a lot of work for film and TV as a composer. That’s a whole career I never envisioned would happen for me. I expanded my musical world, because a lot of what I did was instrumental. I had to listen to a lot of stuff during that period. When you work on a TV series, it becomes your life. It’s all you can do at the time. I put everything into it.

I understand you’re considering an expanded version of the band’s second album, Secrets of the Alibi, which celebrates its 30th anniversary this year.

We’ve talked about that. Universal has been very supportive. It was their idea to go beyond the original Big Blue Sky release and include the unreleased stuff on it. So, we’re talking about that for future releases. I see potential future re-releases as a cool vehicle for getting our unreleased music from those eras out. They’re for hardcore fans because they are demos that were done quickly, without the intention that they would come out on a release. But I think people have found it very interesting to hear the genesis of where The Pikes came from.

As for a possible Secrets of the Alibi 30th anniversary tour, I think it would be on a smaller scale. The Big Blue Sky 30th anniversary tour is the first time we’ve gone across the country in one fell swoop. We learned some stuff from that. There were some enjoyable things about working that way, but I think we’d do it in smaller chunks next time as opposed to a month-and-a-half straight.

Provide some insight into the new album the band is working on.

Last February, we were at the National Music Center in Calgary recording new material. We actually did two gigs there as part of the Big Blue Sky 30th anniversary tour, one of which was filmed for a TV show called Stampede City Sessions that airs before Austin City Limits on PBS. When we first visited, we learned they had the original Rolling Stones mobile recording truck. It’s on display and it’s functional. They have the original console used to record albums for The Stones, Led Zeppelin, Deep Purple and many others. They also have all this vintage gear in there.

We recorded mainly in Live Room "A"—a nice big room where we could all play together at once live off the floor and still achieve some separation to minimize bleed. We used Control Room "A," also known as the Trident Room, with Graham Lessard engineering, and additional engineering from Jason Tawkin. They’re both great engineers with great ears.

For these sessions, we chose not to exchange tapes in advance. We went in with our songs and just did them, together. The new material has lots of vocals, and we've tried to keep the three-voice flavor with Bryan, Kevin and myself. Really, it's whatever serves the song best. It's still such a cool thing to have three vocalists.

We did the material as live as we could get it—two guitars, bass and drums, and once those tracks were set, we followed with overdubs, depending on the particular song. We also wanted it to sound really warm, and that's where the vibe of the 1975 Trident console comes in.

The new music is a cool combination of aggressive rock music, silky pop and atmospheric folk-roots stuff. Some songs were well-defined with fairly elaborate demo recordings, and some were improvised and jammed out to get the right feel. I'm honestly blown away by our new material, and I feel really good about what we’re doing. There’s some great rock riff activity happening, and some very otherworldly vibes as well. It’s exciting, especially having not recorded new music with the band in 15 years. We’re looking at this as the first phase of recording. We’ll do some follow-up sessions and ensure it gets mixed really well. Right now, we’re thinking about a spring 2019 release. I am always amazed at the talent of my friends Don, Bryan and Kevin.

Describe the beginnings of your path as a solo artist after The Pikes broke up in 1993.

I never really had thought about doing a solo album or even having a career as a solo artist. The Pikes were my world and the breakup in 1993 was a confusing and depressing time. This entity I had devoted so much time and effort into just crumbled and I could see no way of it continuing. There was a lot of tension over the previous year and I was pretty burnt out from it. When the smoke cleared, there was this opportunity to record demos to present to Virgin for the possibility of a solo deal with the label. I didn't do anything about it for a while. It took some time for me to adjust my thinking in terms of attempting to forge a new path as a solo artist. I didn't actually start on any new songs until 1994.

The thing that actually brought me out of my mental quagmire was Due South. The Pikes were officially done in June of 1993. Donny called me and said that someone from the Feldman Agency in Vancouver had contacted him to ask about something to do with a TV show. I called Janet York at the agency and she proceeded to tell me about a pilot movie that was currently being shot in Canada, and that the producers were looking for someone to write a potential theme song for it. She described the plot to me, about a Mountie from the Yukon whose father, also a Mountie, was murdered, and his subsequent journey to Chicago to track down the killer, enlisting the help of a Chicago detective. It was very interesting. I started writing down words and musical ideas as we chatted, and I could hardly wait to record them into my cassette recorder. In less than an hour, I had written what would become the theme song for Due South. It turned out to be quite a life-changer, although I didn't realize it at the time.

In the meantime, Bryan had been contacted by Doug Chappell at Virgin as he had become aware of the possibility of working on the song. He contacted me about collaborating on it. It happened that Bryan was going to be in Saskatoon shortly after that, and we got together to talk about it. He decided he would prefer to write a potential song for it himself and we agreed that we would work on each other's song with the intention of having one of them be chosen for the show. We compared notes, and ended up going into Donny's home studio in Saskatoon to record demos of the songs with Donny and Ross Nykiforuk.

Both songs were very different and we submitted them to the agency shortly after. A few weeks later, I called Janet to see what had happened, and she told me that they loved the one that originated with me. Bryan had contributed a stellar signature guitar line to the song and we shared the writing credits equally. A short time later, I received a call from the agency again, asking if we would like to record a demo for the music score. I contacted Bryan about it and he wasn’t interested in doing it. I believe he was already recording demos for a solo album.

So, I sat down with a VHS tape the Due South people sent me that had rough cuts of some of the scenes in the pilot movie. With my limited knowledge of film scoring, I came up with some music that felt good to me for the scenes. I was just roughing it, going by feel, and using organic acoustic instruments—mainly guitar and harmonica. I recorded the music cues—I didn't call them that at the time, as I didn't yet know the terminology—at Donny's home studio, and then sent them off to the agency. I received a call a couple of weeks later from Sam Feldman, who said the producers really liked what I had recorded. I was living back in Saskatoon at the time and they wanted me to go to Toronto and meet with the people from the show. Things were happening quickly and I was a bit tentative about it all. Sam convinced me that this would be a good thing, and the next day I flew to Toronto.

Lots of stuff happened in Toronto and I became a composer on the show along with Jack Lenz and John McCarthy. Both of them are extremely talented guys who became good friends as we worked together on the pilot movie and subsequently the series, which ran from 1993-98. It was a steep learning curve, but ultimately began a whole other career for me as a composer for film and television. I credit Paul Haggis and Jeff King for giving me a new lease on life in music.

I found I had a good instinct for writing to picture. Since Due South, I’ve composed for many different productions. I've been fortunate to be nominated for two Gemini Awards—Canada's version of the Emmy Awards—for the 1995-96 season of Due South and again in 2013 for the series Dust Up, when the name of the awards changed to the Canadian Screen Awards.

When we finished the pilot movie for Due South, my interest in recording solo material was revived. I was getting my confidence back. I booked myself into Creative House Studios with my pal, the late Les Cantin, who The Pikes had recorded numerous demos with, and I began working on the songs. I recorded the first four in a bit of a piece-by-piece fashion. It took a while. I submitted them to Virgin and really didn't get a definite response right away. Ultimately, they passed on them, as they did with Bryan's and Donny's material as well. In this in-between time, I got the gig composing for a film titled Paris or Somewhere, and Ross Nykiforuk and I worked on it together. We won a couple of awards for the score—a Saskatchewan Media Production Industry Association award in 1995 and an MMPIA Blizzard in 1997.

I wrote a song for the final credits, which the producers loved. At that point the movie was yet to be titled and they named it after the song “Paris or Somewhere.” That tune ended up on what became my first solo album Mouse. The album also included the closing credit instrumental piece from another film Ross and I composed for at that time titled Strange and Rich.

Even though Virgin had passed on the demos, I decided to plow ahead with finishing the album. I put together a band consisting of Joel Grundahl on guitar, Wayne Pearson on drums, Cory Hildebrand on bass, and Ross Nykiforuk on keyboards. I played guitar and we cut five songs live off the floor in two nights at Creative House Studios, overdubbing Warren Rutherford's pedal steel parts the next night.

I was going back and forth between Saskatoon and Toronto at that time during 1994-95, working on the first season of Due South, and John McCarthy introduced me to Aubrey Winfield, the owner of Iron Music Group, an independent label distributed through BMG. Aubrey liked the album and we clicked. Mouse was released in the autumn of 1995. The first single "Strawberry Girl” and a subsequent single "Times Change" both cracked the Top-40 AOR chart in Canada, with the videos receiving a lot of airplay at MuchMusic and Country Music Television. We actually filmed five videos in total for the Mouse album.

Because I was working on Due South, I really didn't get out in a big way to promote the record until the spring of 1996. I toured with the band across Canada after an initial solo promo tour in September 1995, and we played a lot of dates through 1996 into 1997. I didn't record another full solo album until 2006. After Mouse ran its course, I was back in Toronto working on Due South. In total, I scored 66 one-hour episodes plus the two-hour pilot.

When the series wrapped in summer 1998, I moved back to Saskatoon from Toronto with my family. I composed music for a number of other series when I moved back there, including 39 episodes of Cotter's Wilderness Trails, 26 episodes of Sweetness in Life, Body and Soul, The Dinosaur Hunter, and a number of other documentaries and dramas. I also began to record voiceovers for advertisements, PSAs, documentaries, and other productions.

When The Pikes regrouped in 1999, you shifted into a dual career, alternating between your band and solo work. Tell me how that decade unfolded for you.

The Pikes did a Canadian tour after Virgin released Hits and Assorted Secrets in 2000, the first of three best-of packages that would come out. We recorded and released Live 2000 and Truest Inspiration in 2000, and It's a Good Life in 2003. We’ve continued to perform live since 2000, with a few extended hiatuses.

In 2005, I was approached by Marshall Ward, a professor of art at the University of Waterloo and also an independent filmmaker and music writer, about being filmed for a documentary about writing and recording music. Marshall and his crew flew to Saskatoon and shot me working on a song at Ross Nykiforuk's Cosmic Pad Studios called “Love Will Set You Free,” and that became the title for the film. I credit that project with being the catalyst that got me back to writing and recording new songs that would firstly become the three-song EP Love Will Set You Free, and then in 2006, the album Redberry. I was accompanied by my niece Brianna Burtt on the song, and it gave me the idea to have some guest female singers on what was to become Redberry. I was joined on the album by Andrea Menard, Brianna, Canadian Idol runner-up Theresa Sokyrka, and Serena Ryder. The album was recorded with Ross at Cosmic Pad, except for a session with Brianna and Serena which was recorded at Jack Lenz's studio in Toronto.

Serena has gone on to become a huge star in Canada. We first met when The Pikes' publisher, Peer Music, suggested Serena record a version of "Girl With a Problem" for potential use in a TV series titled The L Word. Serena, Bryan and I spent a couple of days recording the song at his home studio in Toronto. She took the reins with the song and we recorded a very cool version. At the time Serena was beginning to become known in Toronto. This was prior to her signing with EMI. The first time I heard her sing, I was blown away by her voice. She’s an amazing talent. It's so cool to see the success she has achieved. Andrea, Theresa and Brianna are all fantastic singers too, and it was so much fun to have them with me on the album.

The early 2000s were a challenging time for me personally. My drinking was escalating and becoming more and more of a problem. In October 2006, I entered a treatment center in Quebec. Redberry had just been released and I had a tour booked for the Maritimes as a co-bill with Saskatchewan artist Joel Fafard. I remember doing an interview on the pay phone in rehab with the journalist Bob Mersereau, and coming clean about where I was and what was happening. I think Bob appreciated my honesty. The day I was released, I flew to New Brunswick and began the tour with Joel. He's a great guy and we had a fun tour over the next couple of weeks. I stayed sober for the tour, but when it finished and I returned to Saskatchewan, I began drinking again. There were a number of lost weeks then that resulted in me finally sobering up in late March—March 25, 2007 to be exact. The fog started to clear, and I was focusing on my recovery.

I received a call in June 2007 from Larry Leblanc, a renowned music writer and a longtime friend of The Pikes who was managing a great singer-songwriter from Kelwood, Manitoba, by the name of Alana Levandoski. He suggested I do some writing with her. We set it up and I went to Manitoba and wrote a couple of songs with Alana. That got me thinking about co-writing with some other writers and I decided to plan a trip to Nashville to co-write—something that had been suggested to me for some time, which I had not acted on. So, I flew down to Nashville in early December 2007 after setting up some writing appointments in advance through some of my music friends in Canada.

The first person I wrote with was Tim Taylor, a transplanted Canadian and a great songwriter. We had a blast writing together, in addition to the sessions I had with other writers. Tim has become a close friend and now is my favorite co-writer. I look forward to doing lots more of it with him in the future. Co-writing became another interesting skill to learn. I've always been a fairly solitary writer and I'm still learning new things about songwriting in every situation I encounter. The songs I wrote on that trip, along with some others I had cooked up on my own, became the International Superstar album, recorded in early 2008 and released later that year.

I should mention I also recorded a Christmas album in 2006 of classic Christmas carols called, aptly enough, Merry Christmas. In addition, I released a live album recorded in 2008 for the national CBC radio series Canada Live in Concert at the Royal Saskatchewan Museum in Regina.

International Superstar was definitely a little more country-sounding than my previous solo albums, although I've always loved using pedal steel, mandolin and other instruments associated with that genre in my music. I toured across Canada with a trio for that album with Dr. Dan Downes on guitar, John Morrison on drums and myself on bass. We had some good adventures. The album was released on Busted Flat Records, distributed through Universal Music. Busted Flat released all of my albums until 2014's Flora Vista.

During the 2010s, you continued exploring country and roots elements, as well taking some interesting detours. What’s your perspective on the distance traveled so far this decade?

In 2009, I connected with guitarist and producer Jay Buettner, a former Saskatonian living in Vancouver, who had recorded guitar on the International Superstar album. He became the producer for my 2010 release Jay Semko. We recorded Nashville-style—live off the floor with great session musicians in Abbotsford and Vancouver, British Columbia. I was regularly going on writing trips to Nashville at that time, and as a result there are a number of co-writes on the album.

I’ve been releasing singles to Canadian country radio since International Superstar with consistent airplay, and all of my solo albums have charted highly on Canada's Earshot folk, roots and blues charts, sometimes achieving number one status.

In 2011, I released Force of Horses, which won the Saskatchewan Country Music Association Award for Roots Album of the Year in 2012. I guess what I sometimes consider in my music to be "country"-sounding is more easily categorized as "roots." I really just try to write good songs that mean something to me and record the best versions I can of them.

In late 2011, I went to MCC Studios in Calgary to record Sending Love, which was released on Valentine's Day in 2012. It was a departure in that all of the songs were self-penned. There were no co-writes and all had a "love" theme. It’s a very personal record. It was fun and challenging to get back to a more personal writing experience. I have very nice memories about recording the album in Calgary with Johnny Gasparic and Dave Temple.

In 2013, during a trip to California with my partner Colli, she became ill and our stay was lengthened while she recovered. I started getting inspired by the environment and reflecting on my life, and purchased an inexpensive guitar to write with. Those were the beginnings of the Flora Vista album. There is a decidedly "California" vibe to it, but maybe that's just because of the memories I associate with writing the album. There are a few co-writes on the album. I recorded it back in Saskatoon with Randy Woods. It was a very relaxing and enjoyable experience.

Although I certainly have a firm grasp of popular songwriting, I like to mess with stuff. My rule with my solo albums is that there are no fixed rules with the songs. As a result, there are some different trips in the music on songs such as “Surrounded by Love” and “Junkie Pride” from Flora Vista. “Junkie Pride” is interesting in that I actually wrote it when I was in rehab in 2006. It took eight years for me to be comfortable enough to look at myself honestly and thoroughly to record that song. “Clean” from Flora Vista is a bit like that too. It's strange and enlightening for me to look at songs after the fact. “Girl With a Problem” was really about me projecting my problem onto someone else. It's much easier to point out someone else's issues than to actually deal with your own.

Flora Vista was released on my label, Inner Expression Records. Although I still have a great relationship with Busted Flat Records, I felt it was time for me to return to my own label. It just seemed like the right thing to do. Flora Vista won the Saskatchewan Country Music Association Award for Roots Album of the Year in 2015. It's nice to be recognized, but everything is cyclical and you really have to love what you're doing to continue what I and the guys in The Pikes do. Passion is completely necessary and simply not even considered—it’s just accepted and part of the DNA.

I love everything about songwriting. The cool thing about having written for so long is the self-editing I can do very quickly. I also recognize the magic moments when they're happening and know when it's time to pick up the pen, the recorder or the instrument. Working on film scores really expanded my musical world and opened my mind. Something related to that is the instrumental album I released in 2016 in collaboration with Randy Woods, under the name Sacred Rings of Jupiter. It’s atmospheric music. I find that I listen to classical and instrumental music more now than I ever have. I find I listen differently to music than I did when I was younger. It’s a natural evolution.

Give me a preview of your forthcoming solo album now in progress.

I’ve been working on my next solo album off and on over the last year. Half of the album is pretty much tracked. I’m doing it again with Randy Woods. It’s going to be pretty roots-oriented. I think I’m going to put it together with Mike Pierson on drums and Randy on guitar. We’ll get some other people involved and cut the rest of the tracks live off the floor. I did that with Flora Vista and it was really quite fun to do. I might revisit a couple of the songs I’ve already done. My plan is to have it ready to go in April.

I’m having a great time working on all of this new material. It’s such a vast and wonderful world of music that I continue to explore between my solo work and The Northern Pikes. Every time I write a song, make a recording, play a gig, or do anything with music, I’m still always learning something. I'm kind of rediscovering the bass these days, too. It's so incredibly satisfying to get right in the pocket. Music is just in my blood. It's like breathing or eating. It’s necessary for me. And if you’re someone with an addictive nature, as I am, what could be better than the addiction of music?

Bryan Potvin

What’s your perspective on the value of music and its ability to connect people in these challenging times?

I feel that in 2017 there was an absence of artistic participation in reaction to the political landscape. There was a strange lethargy. I don’t know why. I also don’t know if the world is any more amped up than it was before, because by and large, it’s a peaceful world compared to what it has been over the last couple of thousand years. I know people are facing serious challenges, but we’re fortunate, for the most part, as a society.

I just finished my first term at Berklee doing a BA in Guitar Studies, which included a humanities course on the history of music that goes to 1750. I saw that music has served a comforting purpose for people for a very long time. And as a species, we’re sort of nostalgic from a very young age. We like repetition when we’re kids and we seem to like it into adulthood.

Everyone in the band is now in our fifties and we can play the nostalgic card now. You can’t do that when you’re 20-25. We’re moving forward in a progressive way, with one foot in the nostalgia camp and one foot in the trying-to-be-relevant camp as we come up with new music. So, the door is open and we’re going through it with a new guy onboard, Kevin Kane, who’s now the fourth guy in the band. He’s a writer and vocalist I’ve been working with for awhile as a duo. My worlds are colliding in a good way and it’s really a lot of fun.

What do you make of the generational impact Big Blue Sky has had?

A few folks have told me how important that record was to them as a young person, and how it got them through some challenging times. I know that sounds like a cliché, but it’s true and it's widespread. People use music to deal with tough situations. When someone says that to you, it speaks volumes and raises what you do above the vocational aspect of the work—the job part of being a musician in which you’re trying to make a living. When someone says our music really helped, suddenly the job part doesn’t matter and it’s a pretty awesome feeling. It’s unique to this job in some ways.

Do you consider being a musician more of a job than a craft sometimes?

Some days I do. When I got up at 4:30 am to drive to the airport to go to Spruce Grove, Alberta to play five songs with The Pikes in minus 35-degree weather on New Year’s Eve, that was a job. It’s important and we have to do all the promo stuff. It wasn’t a paying gig. We got a small honorariam, but got to sing in front of a lot of people.

Give me your view on how Big Blue Sky (Super-Sized) came together.

It was really kind of a riffing thing between us. Don has been the curator of the band. He has meticulously kept recordings and footage of the band over the decades. He knows where everything is. Jay and Don have scads and scads of unreleased songs from the Virgin years. It was fun to release that stuff on the reissue. I hope we’ll do more of that over the next few years, because some of it is pretty good.

The Horseshoe Tavern recording on Big Blue Sky (Super-Sized) was something I was given 10 years ago by Doug McClement, a Canadian audio engineer. He was going through his closet one day and found a quarter-inch tape of us. He asked me if I wanted it and I said “Hell yeah!” So, that was a natural addition to the package.

You demoed nearly 100 songs prior to recording Big Blue Sky. Describe the process of arriving at the final track listing.

The tunes tend to just pull rank naturally. We would generally learn five or six tunes, mostly penned by Jay at that time, capture them in someone’s basement, and then go into the studio to cut them. It’s obvious that there are songs that are just better than others. I’ve seen that process for Jay as well. People tend to write songs in clusters and in general, there’s a certain percentage of those songs you’ll be playing 5-10 years later, and the rest will sit on a shelf somewhere, unreleased.

“Things I Do for Money” was the track that pushed Virgin over the edge and got us signed. It was part of a cluster of five songs and we haven’t played the rest of them since. So, you live for those sparks. It’s unreasonable to think everything you write when you sit down will be good. But you try. Every now and then, you get lucky.

Sometimes a gem slips through the cracks, like “Deep End of the River” which we included on Big Blue Sky (Super-Sized). I really enjoyed reinterpreting that for the tour. So, the music is never dead. Sometimes, it’s just parked for awhile. The 10 songs on the Big Blue Sky Unreleased disc of the reissue are tunes that hadn’t been given proper justice. At the time, Virgin felt the same as we did about the main album’s track listing. We had a body of work that included material from our independent releases. Some of it worked really well and needed to be re-recorded and put on the record.

What step forward do you feel Big Blue Sky represented for the band after its independent releases?

I think it was a little bit of an extension of what we created on our own. The first two recordings didn’t have a drummer playing on them. The first, self-titled one from 1984 had a funny-sounding drum machine on it, but it worked and we were proud of it. It was tight. We couldn’t find the right drummer at the time, so that’s how we did it. The second recording, Scene in North America from 1985, was more strangely complex, because we did have a drummer named Rob Esch, but he decided to use drum programming and then play live cymbals over top of that. What was really strange is Rob was a great drummer, but didn’t play drums on it. I can’t rememer why we decided to do that. It was Jay, Merl and I, along with Mitch Barnett, in the studio amaking Scene in North America. What we were left with is a crisp, kind of staccato-sounded record.

Big Blue Sky is a grown-up version of Scene in North America, when it comes to production. It was a very tight record. There aren’t a ton of ride cymbals on it. The guitars are pretty clean for the most part. I was really into Johnny Marr at the time and trying to sound like him. I was trying to layer these rich, single-coil kind of Stratocaster tones on it. We tired of having such a tight approach, and we tried to make the next album, Secrets of the Alibi, a little more rough and ready, with more ride and crash cymbals, and hi-hat.

But the sound of Big Blue Sky was the one we were looking for at the time and we were very happy with it. I think it sounded unique without sounding particularly of its time. I don’t think it sounds overtly New Wave or anything. It’s not what commercial pop or rock sounded like in Canada at the time. There was still this twanginess that came through the guitars. I also think the core of The Pikes sound of the time was the combination of Jay and Merl on vocals. The way those guys constructed harmony was fundamental to who we were back then.

Big Blue Sky was full of unique arrangements. Where did the instinct to go beyond conventional song structures come from?

There was a lot of push back in those days. Your worldview changes over time. The band, in some ways, formed around what we were not going to be. I know that’s not a new idea. A lot of bands are born from people wanting to buck the system. I think the alienation we experienced living in the middle of nowhere with no Internet contributed to that. We had one cool record store where we’d go to buy three-week-old NMEs to find out what was going on in the world, musically. Those were our lifelines. Then we’d kind of see what was going on around us and push back against it. We started working on music that was different and we became a band a lot of people hated in the area because of that. Maybe that’s a part of the reason how we came to sound different.

Arranging is part of the writing process for me. I often have a detailed arrangement in my head, even as I’m still carving out a lyric or refining melodies. We’ve always treated the song as king. At a certain point, the song always tells you what it wants you to do with it. You’ve got to listen when that happens.

“Jackie T” and “Teenland” are songs whose arrangements didn’t change after their inception. We felt “Girl With a Problem” needed a drastically different arrangement compared to the original demo, which was more melancholy. We’re also very cognizant of how we end songs. We try to be creative in that way too.

Elaborate on what you mean when you said some people in the area hated you.

I played in a group called Doris Daye and we nearly got beat up a few times playing gigs. I never actually got beat up, but I was threatened several times. Even The Idols and The Pikes in the early days had problems when we played rural towns. We would head out to those places and we’d sometimes run for our lives at the end of the night. It was pretty scary. There were audiences that had people who had that “I’m out for a beer and a fight tonight” mentality. There was violence all around. When you didn’t play the music they were hoping you would play, that caused issues.

Playing “Pump it Up” by Elvis Costello in a bar in Weyburn, Saskatchewan in 1979 or 1980 could get you beat up, especially if you were all wearing matching jumpsuits. [laughs] I ended up in a headlock in Weyburn with some guy walking me down the street in the crook of his arm. The Idols also used to bring these Fred Flintstone inflatable dolls on stage during a song and beat them up. It was kind of a freak show and the locals often didn’t appreciate the art. [laughs] Ashtrays would get whipped at us onstage sometimes. It was just life as it was back then. A little unpredictable in the smaller centers. You never knew what you were going to get. It was a crazier time. I’m glad those days are over. [laughs]

What was it like for you to revisit Big Blue Sky across a coast-to-coast Canadian tour?

It was fun. We had never played “Never Again” live before and that was one of my favorite parts of the night. “Big Blue Sky” was a ton of fun too. It was the opening song of the show and it was a blast. We spent a lot of time putting together a complete evening and wanted it to be as tight as possible. We’ve played a lot of gigs in recent years, but we haven’t put on a show like this in a long time, so that was really satisfying. The three of us debriefed since the tour and there’s a lot of excitement between Jay, Don and I. We said “Let’s do it again.” We’re back to enjoying working together on a deeper level.

The other interesting thing for me when touring this record is that Merl’s voice was out of the picture. We didn’t come up with a substitute for Merl. We brought Kevin Kane along instead. We could have found a musician to do Merl’s trip, but then I wouldn’t have had the experience of singing the songs during the first set I did. I sang about half of those songs that Merl used to sing. I worked on those songs for weeks before the boys showed up to start rehearsing. I couldn’t slide back into my old self where I just played guitar in the shadows.

Remember, I didn’t sing on Big Blue Sky, originally. That wasn’t my role at the time. The band was configured as a vocalist who would sometimes play guitar, hop around and do his thing, and a bass player who was singing lead too and writing most of the material. I was content to color the music with my guitar. Jay was very encouraging about everyone participating in writing. He always wanted to hear other people’s ideas. He’d say “You’ve got a song? Let’s hear it.” It was always a friendly ecosystem for me to develop as a singer-songwriter and it served us well for this tour. I think it would have been tough for Jay to have sung the whole of Big Blue Sky on his own. I was glad to help.

What made Kevin Kane an ideal fourth member?

A lot of this stuff is interpersonal. For example, bands that have been on the road a long time will hang onto a great crew that they really trust. There needs to be a working relationship and chemistry. It’s almost a family. That’s an important part of the process. There were a lot of options to fill that fourth role, but there wasn’t a lot of discussion about it. My relationship with Kevin was already established. We were having fun playing shows and doing our duo thing. It’s not a big serious thing, but we do play quite consistently. We’ve done 130-140 shows in the last few years.

When you go out on a big tour like we did for Big Blue Sky, that tests someone’s mettle. You find out who’s in this for real and who’s not. Kevin’s a lifer. He’s just going to play until he isn’t here anymore. I hope I can do the same thing too. I would like to play as long as my body can deal with it. I see a limit to the high-impact touring we’re still doing coming up, but not right away. By the time I’m in my sixties, I hope I’m not sleeping on the tour bus anymore. Maybe I will want to. [laughs] We’ll see. It’s a bit like camping.

I wasn’t the one that brought up Kevin. Jay and Don came to me and said “Kevin could be a good pick for this.” I thought “Well, I suppose you’re right. It should be easy. He already knows some of The Pikes’ tunes from playing with me. It’s not like he’ll need an audition process.” Also, I already know what it’s like to live on the road with him for seven weeks. He’s also walked down the same roads we have with The Grapes of Wrath. He’s his own artist. He has his own tunes. It felt natural for him to be a part of this. His musical participation in the playing of Pikes songs is great. He carves out great guitar parts. His vocal ideas are fresh. It has been marvelous. The fact that he brings his songwriting skills and success to our show is pretty special. People are always going “Wow, I bought a ticket to see The Northern Pikes, but I heard a couple of really awesome Grapes of Wrath tunes that night too.” So, that’s been a lot of fun.

As you intimated earlier, your role in the band changed dramatically over time. What was it like for you to evolve out of Big Blue Sky into the role of a singer-songwriter and frontman?

It felt pretty natural. I have an animated quality on stage that I’ve maintained since I was young. I do love being up there. Some people don’t actually like being on stage, but they do it anyway. But to me, being given additional responsibilities like singing seemed like fun. I was happy to take that on. It’s hard for me to imagine not having taken this route now, because I might have actually become a little bored by this point otherwise. Exploring songwriting made me take things further. It felt natural to me.

When The Pikes were at their peak, we had three songwriting engines firing at the same time between Jay, Merl and I. It was exciting and a lot of fun with us all bringing in material. Sometimes we’d go to somebody’s house the night before a session with acoustic guitars and bang songs out and share our ideas. I also enjoyed shading other people’s songs. But it felt great to sometimes take the reins, too. I’m very lucky to have been part of a band where people were encouraged to present their songs. There are other bands where members aren’t allowed to sing or write songs. That wasn’t the situation with this group. It was always “the more the merrier.”

Describe your guitar philosophy.

It’s about my desire to serve the song. I like virtuoso music. I enjoy listening to it, but it’s just not what we do. We’re a tune band. I play tune guitar. I’m trying to make it interesting. I’ve always been interested in guitarists, particularly when we were starting out, that made sounds that didn’t quite sound like guitar like Andy Summers, The Edge and to a certain degree, Johnny Marr. I loved that stuff and I’d bring some of that sort of color to the songs.

Merl was a more strummy, rudimentary player. He made the guitar sound like a guitar. So, I thought it would be valuable for me to come up with sounds that didn’t sound like traditional guitar. I’d use volume pedals to create swells, sustainers, eBows, and anything I could get my hands on. I was always trying to see if there was something I could add tonally that was interesting. Over time, I kind of moved further and further away from that. My guitar tone is cleaner and has less effects than before. The effects are more subtle now. But I just got a Fractal AX8 effects unit, which has opened up some new ideas. It’s all about different shadings and how I can listen to what the song is telling me to do. I mean it when I say the song says “You should use this kind of guitar. You should use this kind of delay. Do this instead.” I just listen to the music. Even though I have a big bag of tricks, I try not to overuse it.

Reflect on The Pikes breaking up in 1993 after the fourth album Neptune.

That’s a tough one. I kind of regret it in some ways, but in other ways I don’t. So many good things happened in my life after the split, before we reunited in 1999. But I do wonder what would have happened if we hadn’t broken up then. I’ve become a proponent of therapy in the latter part of my life. Had I known the power of it, I might have tried to apply some of it to the band at the time.

It was a case of detoriating relationships within the group. Had we had a stronger outside voice—a fifth voice within the inner circle that we trusted—that said “Take a year or two off. Just get away from each other for a while and go do something else. But don’t take six years off.” Maybe that would have changed things. Breaking up had nothing to do with a lack of success in other territories or anything like that. Things were going great in Canada. We really had excellent support from the label still and they were bummed. They were choked up we decided not to move forward. But we’re here now and everything is fine. Everything shook out the way it did and Merl’s not with us anymore. There were commitment and personality issues at the time and perhaps we needed to step away from it to find out who really wanted to still be in the band and who didn’t.

I recently watched Spirit of the West’s Spirit Unforgettable documentary. In addition to being moved by the very personal, tragic story told in it, I was surprised to learn that band, also signed to a Canadian major label deal, never saw any royalties, despite having gold and platinum records. How did The Pikes fare with Virgin Canada?

We never saw any royalties either. We had mechanical royalties, but everyone gets those who’s a songwriter. The deal wasn’t designed that way, though. There were a few key artists who kept salaries being paid to label staff. But my experience working in A&R at a multinational label after The Pikes broke up in 1993 involved learning what kind of money went into so-called R&D. When you release and promote music, you really have no idea whether it will sell or not. It was remarkable, but the big acts paid the bills. In the context of Virgin Canada, Culture Club kept the lights on at the time. But for The Pikes, all our money was spent on making records, shooting videos and tour support. So, no, we didn’t make any money from the records.

Even the double-platinum Snow in June yielded no royalties?

We’d have to get into the metrics of where all that money went, because there was money generated. There’s no doubt about it. But we spent quite a bit making records, too. It’s all about those lopsided major label ledger sheets that are designed to give you royalty payments only if you’re at the Tina Turner, Bruce Springsteen or Celine Dion level. We recorded in an unbridled way. Snow in June took five months to make at a studio that cost a lot of money every day. The videos were never cheap back then. A video would involve 20 people on the set, including gaffers and best boys. It was insane. It’s unbelievable how much less it costs to make a video today. But back then, the Virgin well seemed bottomless. It was always “Yep, yep. Whatever you guys need.” There was always money. There was also unrecouped debt.

After The Pikes broke up, Virgin Canada funded solo demos for each member. How did that manifest itself for you?