Donate to Innerviews

Since 1994, Innerviews has provided uncompromising, in-depth interviews with musicians across every genre imaginable. And it does that with no trackers, cookies, clickbait, or advertising.

Your donations are welcome to help continue its mission of highlighting incredible music and artists, without any commercial considerations.

Your contributions will be instantly transformed into stories and videos, and cover hosting and web management costs. Importantly, your dollars will help ensure Innerviews remains absolutely free to all visitors, independent of their ability to financially support it.

Please consider making a donation today by using the PayPal QR code below.

The Zombies

Natural Evolution

by Anil Prasad

Copyright © 2025 Anil Prasad.

The Zombies, 2023: Tom Toomey, Søren Koch, Rod Argent, Colin Blunstone, and Steve Rodford | Photo: Alex LakeNearly 60 years after their debut, The Zombies remain one of the most distinctive and enduring bands of the British Invasion. Formed in St. Albans in 1962, the group blends soaring harmonies, baroque arrangements, and pop precision into a unique sound that stands apart from their contemporaries.

The Zombies, 2023: Tom Toomey, Søren Koch, Rod Argent, Colin Blunstone, and Steve Rodford | Photo: Alex LakeNearly 60 years after their debut, The Zombies remain one of the most distinctive and enduring bands of the British Invasion. Formed in St. Albans in 1962, the group blends soaring harmonies, baroque arrangements, and pop precision into a unique sound that stands apart from their contemporaries.

The Zombies’ 1968 album Odessey and Oracle has enjoyed a particularly remarkable multi-decade arc. It was initially released with little acknowledgement or acclaim, but over time, it established itself as a cornerstone of the late-’60s psychedelic rock revolution.

Odessey and Oracle was just reissued in its original mono mix. For the band, which then consisted of late guitarist Paul Atkinson, keyboardist Rod Argent, vocalist Colin Blunstone, drummer Hugh Grundy, and bassist Chris White, this version of the LP provides the most accurate reflection of how the group balanced vocals, keyboards, and rhythm tracks before stereo became the standard.

The album showcases Blunstone’s extraordinarily diverse vocal capabilities. He takes an elegantly-sculpted approach to singing, with each word and turn of phrase shaped by breath and timing. His orchestral phrasing, subtle vibrato, and dynamic shading helped define The Zombies’ identity.

When the band first broke up in 1968, Blunstone launched a solo career highlighted by 1971’s One Year, which was co-produced by Argent and White. Similarly to Odessey and Oracle, it now stands as one of British pop’s classic albums with sophisticated arrangements and introspective, emotional lyrics and delivery.

No-one could have predicted The Zombies would reemerge in 1999, 31 years after their split, to incredibly popular, multi-generational acclaim. It began with Argent and Blunstone performing one-off gigs and eventually transforming into a global touring act. They went on to make five more albums, including their most recent release, 2023’s Different Game, which features drummer Steve Rodford, guitarist Tom Toomey, and bassist Søren Koch as part of the lineup.

The Zombies’ mercurial journey is chronicled in Hung Up on a Dream, a 2025 documentary directed by Robert Schwartzman. The film captures the band’s rise, collapse, and rebirth. It paints a vivid picture of how the group’s uncompromising approach often clashed with the commercial pressures of the 1960s music industry. Most significantly, it offers comprehensive dialog from the band who assess their own story with candor and humor.

The group’s next steps, however, are uncertain. In mid-2024, Argent suffered a stroke and announced his retirement from touring. He said he intends to keep writing and recording. Blunstone is still a force of nature at age 80, and continues flying The Zombies’ flag by performing the group’s material as part of his own shows.

Innerviews spoke to Blunstone via Zoom about The Zombies’ past, present, and possible future, as well as the fascinating twists and turns that have informed his solo career across the decades.

The Zombies, 1965: Rod Argent, Colin Blunstone, Paul Atkinson, Hugh Grundy, and Chris White | Photo: Stanley Bielecki

The Zombies, 1965: Rod Argent, Colin Blunstone, Paul Atkinson, Hugh Grundy, and Chris White | Photo: Stanley Bielecki

What makes the mono mix of Odessey and Oracle so meaningful to the band?

This is how it was mixed when we first recorded it. And I think it has got something special to it. It certainly seems more to the point with me, and crisper and warmer. I just think it's fantastic.

There's been interest in going back to the original tapes and remastering this record as we heard it way back. We first started recording this in 1967 and it wasn’t released until 1968. I think it's wonderful that there's the interest and commitment from people that want to go back and do this.

It's been a thrill for me to hear it as it was originally conceived. It's almost like a historical document when you go back and hear it as accurately as you possibly can.

For me, all those memories come back of those very, very hurried sessions in Studio 3 at Abbey Road, where we were trying to make this album for a recording budget of £1,000.

Do you feel that pressure served as a forcing mechanism for the band to do its best work?

In a way, I do. Today, you have endless possibilities in terms of how you can record. But what it means is you start to lose spontaneity. And there's a major discussion about any little alteration, because there are such diverse ways that you can record now. It makes everything an epic decision.

When we recorded this album, we absolutely did not have the time. And recording was very different then. We were basically recording on four tracks, and you couldn't make all these decisions. You just had to get in the studio and play the music. And that's exactly what we did. And we played it as quickly as possible. We knew the budget was tight and we had to work within those limitations.

We took over a small village hall near St. Alban’s where we come from for a week or two. We played the songs over and over again. When we got to the studio, we knew what the songs and arrangements were going to be.

When we were at Abbey Road, we were just looking for a performance and to capture the right energy. One can make a negative argument about being under pressure, but it also brought out something quite special. There’s an energy on the album that wouldn’t be there if we’d had countless hours to record.

Both The Zombies and you as a solo act were also always under pressure to constantly deliver new material. How did that impact everyone?

I’ve never understood that pressure. Back when we were with Decca, they wanted a single every six weeks. I felt that was a recipe for disaster. They were just assuring your career was going to be short and unsuccessful.

We were touring all the time then. There was no time to write and record. So, everything became rushed to the point of career suicide, really. In America, our follow-up to “She’s Not There” wasn’t released as a single. It was called “Leave Me Be” and we knew it wasn’t a hit record or an A-side of any sort. I’m not being unfair to the song, which is a lovely one written by Chris White. But he also agrees it wasn’t a single.

It was all about the pressure Decca put on us, with some of us only being 18-19 years old. We had only just entered the business and presumed Decca knew what they were talking about. So, we had to release our second single six weeks after the first and suddenly our career took a huge dive because of that.

In terms of recording one album a year, that’s also very challenging if you’re a touring artist. Very often, the standards and material will suffer.

As a solo artist, I was under the constraints of recording an album a year. And if you didn’t record the album, they would put you on suspension and not provide your next recording advance. Looking back, that would have been a small price to pay. It wouldn’t have made any difference.

I wish that when I had started my solo career with CBS that I had said, “Well, put me on suspension then. I don’t mind. I want time to record an album.” Recording an album every year was too much pressure.

What are your thoughts about the stereo mix of Odessey and Oracle, which is how many people first heard it?

At the time, stereo was a very new medium and people were experimenting. They weren’t too sure of what they were supposed to be doing. They were making it up as they went along in a lot of ways. Stereo has come a long way since those days.

By the time it came to do the stereo mix, we had spent our recording budget. So, Rod Argent and Chris White paid out of their own pockets to have that stereo mix done. And again, it had to be done very, very quickly.

It would probably be a better stereo mix if we were doing it now.

Do you feel some stereo mixes from the ‘60s were gimmick-laden in an attempt to test the boundaries of what was possible?

That was true of the whole recording industry then. No-one knew what was going on. Rock and roll was still relatively new.

There were no eight-track machines in the UK at the time, so for Odessey and Oracle, they tried to give us eight tracks in the same way they did with Sgt. Pepper’s. In other words, they put two four-track machines together. But in doing that, they lost one track. So, we were actually recording on seven tracks some of the time.

The Zombies, 1966: Hugh Grundy, Colin Blunstone, Chris White, Paul Atkinson, and Rod Argent | Photo: Stanley Bielecki

The Zombies, 1966: Hugh Grundy, Colin Blunstone, Chris White, Paul Atkinson, and Rod Argent | Photo: Stanley Bielecki

From a big picture perspective, why do you feel Odessey and Oracle remains the subject of such perpetual interest?

There are two specific reasons I can think of. The first is that there are 12 wonderful songs on this album written by Rod Argent and Chris White. Every song has something really special and is a timeless classic. Rod and Chris hit such a wonderful writing streak around this period.

There’s a slight mystery about why it didn’t get much of a response commercially or critically at the time, despite that. And yet over time, it’s been recognized as one of the best albums of the ‘60s, despite it coming out in relative obscurity.

I recall reviews from the period it was first released in which the reviewer wasn’t particularly impressed. I don’t know why that should be. And conversely, years later, people talk about it as a very important piece of work.

The career of The Zombies isn’t typical. Rod and I got back together in 1999. It wasn’t immediate, but after a few years working together, we realized there was an appetite for The Zombies’ repertoire. We started playing more and more Zombies tunes and eventually, we were playing a Zombies show. We thought, “We should really just call this band The Zombies, so people know what they’re coming to hear.”

We call that the second incarnation of The Zombies. We went from playing rooms at the back of pubs to being inducted into The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. It was so great and exciting to see the band grow. It involved the repertoire of the original Zombies, but in a way, it was a completely different beast. We had Rod and I from the original band, but all the other magnificent players had no connection to it.

This reissue is the first to emerge since The Zombies acquired the rights to its catalog. Describe what it means for the band to be in control of its music for the first time.

All bands want to be in control of their music but in the ‘60s it wasn’t really possible. The option was never available. So, it’s very liberating to be in this situation. And we’re involved with some wonderful people who revere The Zombies' catalog.

We’ll be reissuing three more Zombies albums in the next 12 months, so there’s going to be a lot of activity coming up. Hopefully, there will be a reappraisal of what we achieved. It’s really exciting for us and we hope people will hear the music with a different perception.

I think particularly in America, people’s views on The Zombies have changed and we hope the rerelease of these albums changes that further in a positive way.

What can you tell me about the other three reissues?

After Odessey and Oracle, the next one is Begin Here, which was actually our first album. It was recorded in two evenings, very, very quickly. After that, there’s going to be an album of singles.

The fourth release is a reissue of R.I.P., which was the end of the original Zombies. It came out at a time when the label was demanding more product, and it involved a lot of demos that had never been previously released. We went back to them for R.I.P. and realized they were really good songs.

What’s interesting about R.I.P. is that Rod and Chris had started their next band Argent by that point, so on some of R.I.P. you’ll hear members of that group playing. So, it represents a sort of fade out from The Zombies into Argent.

There was a single released during this period called “Imagine the Swan.” It’s written by Chris, but it’s actually all Argent on it. We’ll include that on the new edition of R.I.P. that’s coming up.

Colin Blunstone, 2025 | Photo: Andre Eccles

Colin Blunstone, 2025 | Photo: Andre Eccles

You’ve contended with virtually every music industry model that’s emerged. How have you handled the shifting complexities?

The Zombies never followed any trends, including from the music business side of things. I’m not a very sophisticated member of the industry, but I go back to the principles we’ve always used, which are just write the best songs you can, record them to the best of your ability, promote them as best you can, and then get out there and tour. In those ways, my life hasn’t changed that much.

I can’t pretend to understand the nuances of the music industry. I never have—not just now. I didn’t understand it in the ‘60s and I don’t understand it now. I have to see it in a very simplistic way, because otherwise it can really start to destroy you as an artist if you focus on the vagaries of everything going on at the moment.

When one watches early Zombies footage, you come across with a quiet confidence and elegance as a frontman right from the start. That’s despite being thrust into the national spotlight on television with little prior experience. How were you able to pull that off?

I originally wasn’t the lead singer in the band. I joined to be the rhythm guitarist. So, I’ve always been quite shy and introverted. When by chance I was appointed lead singer, I was a bit overwhelmed, to be absolutely honest. And that was when we were an amateur band.

The strides that happened occurred very quickly. Suddenly, we were on major TV shows. I look back and wonder how any of us managed to do them, because there’s no formal training that goes into it.

One minute, you’re playing to 200 people and the next minute you’re playing to millions of people on TV—and you basically sink or swim.

I’m very glad you feel I looked in some way confident or polished. When I look back, I can see someone who was excited to be involved in what was happening with the band. But I can also see someone who was fairly naïve and didn’t quite know what was going on but was doing the best they could.

The Zombies have played in front of some really big audiences, but that’s not the same thing as TV. I think TV has always been a bit of my Achilles heel. I think my performances have varied quite a lot on TV. Some have been quite good, but there have been one or two shaky ones. Whether those have been obvious to others, I don’t know. But I was feeling the pressure a bit on those.

How do you look back on The Zombies’ recordings that emerged during its second incarnation?

I look back with great pride on all the albums we made with the second incarnation of the band. They were all tied into touring. Making those records provided more relevance for touring. It meant we weren’t always looking back to the ‘60s, although we played some of those songs, too. In order to keep the band going, we had to be writing and recording new material. So, those albums were really important for us and seemed to be received very well.

Originally, we brought in people who would come out and tour with us. We were so fortunate that the people we put together also worked so well in the studio.

We mostly recorded Rod’s songs. We’re really lucky he can write so many sophisticated, great songs. We also recorded them very quickly. It was a pleasurable experience to work with these brilliant musicians.

The last album, Different Game, was recorded at Rod’s studio with him producing. It was a very relaxed environment and great fun to do. It was mostly recorded with the band playing live and me singing live. A lot of the solos were live as well. The only thing we overdubbed were backing vocals on the last two albums. That made it so much more enjoyable to record. There’s a real energy involved in recording live. A lot of bands record completely separately and then send their performances into a central studio. For us, it works best when we’re all in the studio together.

As I mentioned earlier, after Different Game, we were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, which was a magical experience. Susannah Hoffs from The Bangles gave a wonderful induction speech which was very moving. When Rod and I got back together again in 1999, we weren’t sure anybody would remember any Zombies songs. So, the reaction was a lovely surprise.

Suddenly, we saw all this enthusiasm and respect that we didn’t experience when The Zombies first finished in 1967. At the time, we felt really unsuccessful. So, to have a worldwide interest in The Zombies was quite breathtaking and wonderful.

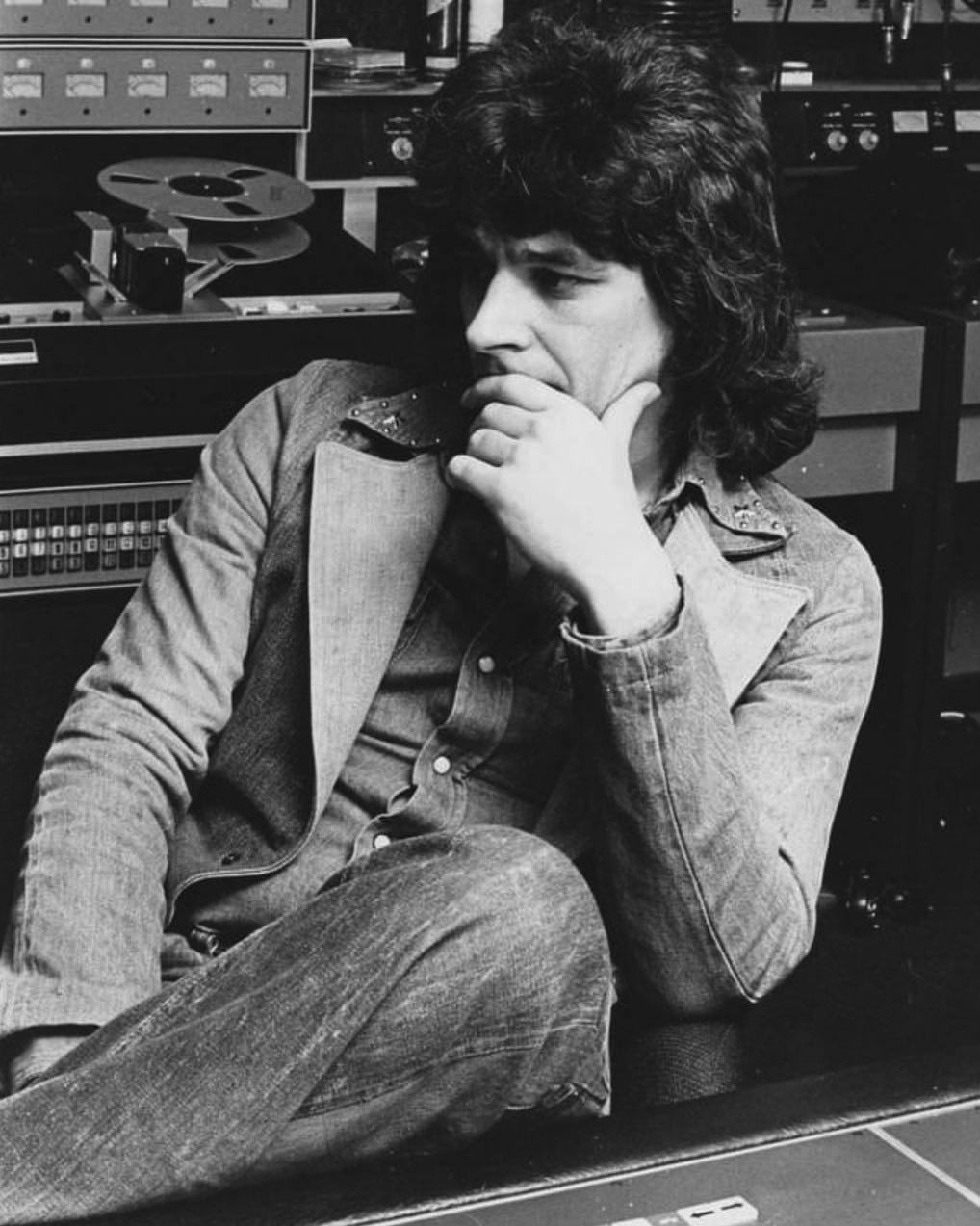

Colin Blunstone, 1973 | Photo: Epic Records

Colin Blunstone, 1973 | Photo: Epic Records

A lot of your solo music is inextricably linked to The Zombies in terms of personnel and influences. What’s your perspective on that crossover?

I was really fortunate. I left the business when The Zombies finished. At that point, the three non-writers were absolutely penniless, and we all had to get jobs.

I didn’t choose a job. I took the first one I was offered, which was as a clerk for an insurance company. I didn’t know if I’d ever get back into the music business. And then “Time of the Season” started going up the charts in America in 1969 and I started getting phone calls.

The producer Mike Hurst approached me. He had recorded the early Cat Stevens singles. He convinced me to go in the studio, and I made three singles with him. So, went to Olympic Studios in London and I put vocals on tracks he’d recorded. And for some reason, they came out under the name Neil MacArthur.

I certainly didn’t choose that name. I’m not sure why they did it. Perhaps it was because the first single was a re-recording of “She’s Not There” and they wanted to use a different name. It was an interesting experience, and it got me back into recording again. The first single as dear old Neil was a small hit, so I got stuck with the name for about a year.

One night, I was going back home from a party with Chris White. He was driving and said, “Why don’t you forget the Neil MacArthur thing and go back to your real name?” He said he and Rod now had a production company and that they could produce me. So, they encouraged me to record my first solo album. I was really fortunate to have Rod and Chris produce it.

Peter Vince, a wonderful recording engineer, also worked with us on the album at Studio 3 at Abbey Road. So, I had the same team that worked on Odessey and Oracle.

There were a lot of subtle differences going from being in a band to becoming a solo artist. The making of that album, which was titled One Year, helped that transition occur. I was really familiar with everyone, and they were all at the top of their game.

“Say You Don't Mind," which was written by Denny Laine, was recorded with a 21-piece string orchestra. It’s very unusual with its great string arrangement by Chris Gunning. It’s a wonderful track. I don’t think you would think of it being a commercial song, but it was a really big hit in the UK.

So, suddenly, I was back as a solo artist and up and running. My first solo tour was opening for the first ELO tour. That was a great way to start the solo career.

I really never thought I would record again. There’s so much chance in life and that’s certainly the case for me. I look back and think it was really fortunate how everything came together.

One Year’s impact is ongoing with a 2021 deluxe edition that includes early song sketches, and a new box set chronicling a recent live performance of it. Explore the making of both releases.

I wasn’t sure how the public would react to the sketches, because some of them aren’t really fully-formed songs. They’re very much ideas. But in fact, people seemed to really like them. So, I was really pleased they released it. And in fact, that’s what led me to perform the entire album during a short run of gigs last year. We played One Year from beginning to end during them.

We recorded and filmed the last concert which took place at The Union Chapel in London. The box set, which is called One Year and More Live, includes a DVD, CD, and a big book.

It was a wonderful experience to play the album live. It’s quite challenging because there’s lots of different kinds of music on there. One minute we’re playing a rock and roll tune, and the next minute we’re playing a Bartók-esque string arrangement of a very intimate and beautiful song. So, we had to wear lots of hats when performing it.

Colin Blunstone performs at Union Chapel, London, November 2024 | Photo: Christie Goodwin

Colin Blunstone performs at Union Chapel, London, November 2024 | Photo: Christie Goodwin

What does the future hold for The Zombies, given Argent’s recent health concerns?

A lot depends on Rod. He’s very well and fine. He’s in remarkably good shape. He wants to keep writing and recording, so we’ll have to see how things develop. I don’t think The Zombies are ever going to tour again, but it could be that we will record.

I’ve always maintained a solo career the whole time The Zombies have been together. I’ve reactivated it. With The Zombies having stopped touring, I’ve concentrated more on that side of things.

But we have a new Zombies documentary and the four Zombies albums that are being reissued this year, so I remain very active in promoting the band. However, in terms of writing, recording, and touring, the focus is on my solo career.

I think The Zombies situation will evolve naturally. It might also be that we’ve recorded our last song. I don’t know. I hope that’s not the case and that we will record some more.

The Hung Up on a Dream documentary ends by stating that The Zombies’ friendships are ultimately the single most important element of its existence. What enabled you to remain such good friends without the fractious politics and struggles that have impeded so many legendary bands?

It’s probably just down to our personalities, really. I think we’re all fairly easygoing people. The music business—like lots of other businesses—is quite demanding. You have to find your own way to get through the challenges that the industry sets up for you.

Personally, I like to just be very philosophical about being in a band and focus on recording and writing. There are just so many bumps in the road and you could become a nervous wreck if you take that side of things too seriously. I like to work with people who are very easygoing, talented, and driven. So, when these difficulties come up, there’s always a way through them.

I don’t want to get into fights with people. And it’s very easy for that to happen in bands with the pressures of backstage and big shows. Small things can become big things in these contexts, and it’s easy to get caught up in them.

There’s no-one in The Zombies that has that kind of temperament. We all just work towards writing the best songs we can, recording them to the best of our ability, and playing the best shows we can. Those are the important things. And we just ignore all the noise that goes around all of that to the best of our abilities.

Your voice remains in remarkable shape at age 80. What’s your secret for maintaining such high performance standards?

I think one of the main things was being introduced to a singing coach in my fifties. He made it clear from the beginning that he wasn’t trying to change my voice but make it more accurate and stronger. He was someone who worked a lot with singers from London’s West End, which is the equivalent of Broadway in New York. We’re talking about people who have to sing every night. So, he understood the singing techniques they used.

He gave me a set of exercises I should do every day. Those have helped me enormously. When I’m on the road, I do those exercises without fail, before soundcheck and then before the show. If we’re not touring, I’ll do them a few times a week.

The other important thing is looking after yourself. That’s not something anyone does when they’re 18 or 19. Above all, you must stay hydrated. It’s really important to drink lots of water, as well as eat well and get plenty of sleep. It’s just common sense, really.

Young bands that go on the road don’t do any of those things. They’re often up all night. They want to have fun and probably eat not very good food, and forget to drink water. I certainly was in that bracket when I started. You can get away with that when you’re young. You have to remember that your voice is like a muscle. And whereas you could run all day when you’re young, when you get older, you have to work harder. You have to protect your voice as much as possible.

So, that’s my recipe for being a professional singer who just turned 80. I’m not quite sure how that happened. But I’m still singing in the same keys I was singing in when I was 18.

Tell me about your drive to remain so creative, active, and moving forward at this point in your life.

I would do this even if I wasn’t making records. I’d still stay at home writing songs. It’s what comes naturally to me. I don’t have to work at it. And I enjoy every moment of it.

There’s that old saying that goes, “If you enjoy what you’re doing, you’ll never do a day’s work in your life.” And that’s how I feel about my career.

Watch the video podcast version of the interview: