Donate to Innerviews

Since 1994, Innerviews has provided uncompromising, in-depth interviews with musicians across every genre imaginable. And it does that with no trackers, cookies, clickbait, or advertising.

Your donations are welcome to help continue its mission of highlighting incredible music and artists, without any commercial considerations.

Your contributions will be instantly transformed into stories and videos, and cover hosting and web management costs. Importantly, your dollars will help ensure Innerviews remains absolutely free to all visitors, independent of their ability to financially support it.

Please consider making a donation today by using the PayPal QR code below.

Tony Banks

Beyond the Physical

by Anil Prasad

Copyright © 2019 Anil Prasad.

Tony Banks during the 2018 5 album sessions | Photo: Emily Banks

Tony Banks during the 2018 5 album sessions | Photo: Emily Banks

Tony Banks’ immersive, atmospheric and melodic keyboard work has been at the heart of Genesis’ output since the beginning. His contributions as a performer and songwriter are also pivotal to the history of rock during the group's most active years between the ‘70s and ‘90s. He’s influenced countless musicians with his tasteful playing designed to serve the structural needs of the song, even when they involve flowing, extended keyboard passages.

Since 1979, Banks has pursued a solo career in parallel with Genesis. The entirety of his own rock recordings to date is captured on Banks Vaults, a new eight-disc box set. It features his first five studio albums A Curious Feeling, The Fugitive, Bankstatement, Still, and Strictly Inc. It also includes his score for The Wicked Lady, and Soundtracks, a compilation collecting film work for Lorca and the Outlaws, and Quicksilver. A DVD of promotional videos completes the package. All recordings were remastered at Abbey Road studios, and several were remixed.

The albums feature the talents of many notable and diverse vocalists, such as Kim Beacon, Jim Diamond, Fish, Alistair Gordon, Jack Hues, Nik Kershaw, Jayney Klimek, and Toyah Willcox, as well as Banks himself. Guitarists Steve Hillage and Daryl Stuermer, drummers Vinnie Colaiuta, Steve Gadd and Chester Thompson, and bassists Mo Foster and Pino Palladino are among the renowned musicians contributing to the releases.

Banks chose to shift focus in recent times by pursuing classical music projects. Since 2004, he’s released three well-received albums of his orchestral compositions: Seven with the London Philharmonic Orchestra, Six Pieces for Orchestra with the City of Prague Philharmonic Orchestra, and 5 with the Czech National Symphony Orchestra. Each album was named after the number of pieces on the release and Banks’ desire for listeners to derive their own meaning from the work instead of having their interpretations influenced by a title.

Genesis remains an ongoing topic for Banks. The group has been sporadically active over the last 20 years. Phil Collins left the group in 1996, following the We Can't Dance tour, which saw it play to its largest audiences ever across a stadium run. Banks and Mike Rutherford surprised the world by choosing to subsequently continue with the band and recruit new lead singer Ray Wilson. That lineup existed between 1997-1998, during which it recorded a single album, Calling All Stations, and toured Europe. Genesis then remained dormant until 2007, when the Banks, Collins and Rutherford lineup reunited for the Turn It On Again tour. The group has been in stasis since, given Collins’ well-documented physical mobility issues.

In 2017, Collins surprised the rock world by embarking on a solo arena tour in which he was seated for the majority of the show. His son Nic Collins played drums in his place. The success of that tour has spurred conversations about the possibility of a future Genesis reunion with a lineup consisting of Banks, Phil and Nic Collins, Rutherford, and Daryl Stuermer.

Banks indulged Innerviews in an extensive discussion of his solo career arc, several intriguing Genesis reflections and anecdotes going back to the late ‘60s, as well as his thoughts about the potential for reactivating the group.

What evolution as a songwriter do you feel the new box set reflects?

I was writing my solo material in parallel with Genesis and the style changes a little bit over the period the box set covers, in the same way the Genesis stuff does. I did the solo albums because I had much more material than could ever come out in Genesis, and wanted to have an outlet for them. I'm primarily a writer, though I love recording music as well. So, the albums give me great satisfaction. I was very pleased with them at the time I did them and I'm still pleased with them. I'm not one of those people who tends to rubbish their old material. I think they're still valid and still could be appreciated by the Genesis audience—particularly the older Genesis audience. So, that’s a reason for putting them out this way.

I don't know that I've changed that much over time. I always tend to ramble a bit. That's part of my musical style, which was also my approach within Genesis. Perhaps I did slightly more concise music when it came to the later solo period—a bit like it was with Genesis. But I still had the big, long rambling moments with “An Island in the Darkness,” which is probably the strongest moment on Strictly Inc. which has 15 minutes of music.

The first album, A Curious Feeling, is more of a suite of songs, in a way that might recall something more like “Supper's Ready,” in which some parts were longer and shorter, and some bits were more developed than others.

Throughout my whole career, I've always been looking for unusual harmony, which is what I like. I love the way chords can work together and in different ways. When I did “Watcher of the Skies,” back in the early years of Genesis, there's a particular pair of chords at the beginning with a particular bass note that didn't sound like anything else I've ever heard before. The idea that I could find something that didn’t sound like anything else was intriguing—yet it was two chords that weren’t that peculiar on their own.

I’ve always also tried to look for unusual chord progressions. But I’ve always wanted to make certain it all works together, which is a process I enjoy. I like that approach most within the classical world. Those composers didn’t have to stick to keys. So, the later music of people like Rachmaninoff, Shostakovich and Martinů saw them break a way a little bit from key signatures.

A Curious Feeling photo shoot, 1979

A Curious Feeling photo shoot, 1979

The box set combines entire album remixes, as well as some remastered albums in which only a few tracks are remixed. Tell me about those choices.

A Curious Feeling and The Fugitive were reissued about 10 years ago. We remixed both of them, including doing 5.1 surround versions of them. I think we made them sound a lot better, so those are the versions on this box set.

A couple of years ago, we did another box set, which took a compilation approach, called A Chord Too Far. For that, we remixed some of the tracks from Bankstatement and Soundtracks. When it came to putting together the new box set, the feeling was “We could remix everything, but there’s really no purpose for doing that.” We felt Strictly Inc. and Still couldn’t be improved. They are what they are and they still sounded good. The tracks we hadn’t remixed from Bankstatement and Soundtracks also sounded fine, so we left them. So, those are the reasons. You get some upgraded versions of pieces that were reissued in recent times.

Describe the shift that occurred from your 1979 debut solo album A Curious Feeling to your second effort The Fugitive from 1983.

A Curious Feeling is much more romantic and goes to all sorts of different places. The Fugitive is more of a rock album. By the time of The Fugitive, I was also going through a period when I was feeling more direct. This is around the time of Abacab. I'd done a lot of flowery stuff and I felt I wanted something a little less flowery. So, I gave that a go, which is why the songs are more concise and definite.

I decided to sing on it. I always felt that my voice was not a great one, but it was good enough to front a record like this. There are a lot of singers out there who can't sing that well, but if you're singing your own material, it has a certain kind of something about it. But I did discover when I was singing that I had to find a way of doing it that was convincing, and that required melody lines to be a little simpler, and lyrics to be fairly direct.

I was obviously hoping that maybe one or two songs could end up being a hit, which was a forlorn hope, as it turned out. But a couple were released as singles and did get a bit of radio play—“And the Wheels Keep Turning” and “This Is Love.”

It was fun to do and fun to sing. The singing itself was not a particular problem. I found a way of doing it. But once it came to doing things like videos and considering any possibility of live work, I realized that there's no chance I could go any further with this. I was just not cut out to be a front man. And that's another problem altogether, really. I did a bit of singing after that, but not much.

Fish and Tony Banks, 1986 | Photo: Gavin Cochrane

Fish and Tony Banks, 1986 | Photo: Gavin Cochrane

How did you choose other singers to interpret your solo material?

I've enjoyed working with all the singers I've collaborated with, but the choice of singers is serendipity to some extent. I get suggestions from various sources. Sometimes I say “No, I don’t want to use them.” And then there are people I ask and they won’t do it, which is fair enough.

For instance, with the Soundtracks album, I was just looking for people. Several people suggested I work with Fish for a long time, and he was keen to do it. It was fun. We met and got on really well, and had a great time making what was an extremely unprogressive track called “Shortcut to Somewhere.” It was strange given the fact that Marillion was famous for having an early-Genesis influence. But we did a very straight-ahead pop song, which was quite fun to do.

Toyah was suggested to me by my publisher. I thought she wouldn’t want to work with me because at that stage, she was very much in the punk world. But we met and she liked the piece "Lion of Symmetry" a lot. She did a great job on it. I really enjoyed working with her. It was the first time I'd ever worked with a female singer. It was a different experience because female vocalists have a very different range and offer different sets of possibilities.

In the case of Jim Diamond, I was originally scheduled to do "You Call This Victory” with Julian Lennon, but he backed out. So, I ended up doing it with Jim, who was, again, suggested to me.

On A Curious Feeling, I had Kim Beacon, who I found when someone gave me a tape. Alistair Gordon and Jayney Klimek, who I used on Bankstatement, were suggested to me by Steve Hillage and others.

The only person I actually ever specifically asked to sing on my work is Nik Kershaw, because I was a bit of a fan. I really liked his records and the way he sang. I thought it would be quite a good combination. And he said yes to working on Still. Jack Hues was suggested for Strictly Inc. by Nick Davis, a producer and engineer I’ve worked with. Jack and I got on very well, which was a really good thing.

Reflect on the making of Soundtracks and the period of your career it encapsulates.

I’d originally written music for a scene in the film 2010, which I was summarily sacked from at a certain point, because the director didn’t quite know what he wanted. Later, I played a version of that music to the director Roger Christian, and he liked it. I got hired to do the score for Lorca and the Outlaws, which I’m afraid wasn’t very good and didn’t do anything at the box office. That music ended up as “Redwing” for that soundtrack. I was originally envisioning it as an orchestral piece.

Something similar happened for the film Quicksilver. Someone suggested me, I wrote a couple of things, they liked them and we did the project. Both Lorca and the Outlaws and Quicksilver were quite low budget films. So, I put the music together at home, on my own machines between 1984-1986. I was desperately trying to handle lots of tape machines, U-matics and horrible things like those. It was quite tricky, but I managed to do it.

So, what you’ve got on Soundtracks is that material, as well as three songs I did slightly more professionally in the studio. "Shortcut to Somewhere" with Fish came out of some incidental music I wrote for Quicksilver. The other two songs—"You Call This Victory" with Jim Diamond and "Lion of Symmetry" with Toyah—I wrote specifically for Lorca and the Outlaws.

For Soundtracks, the idea was to put everything together on one album, because even though the films hadn’t really been successful, I felt the music was good.

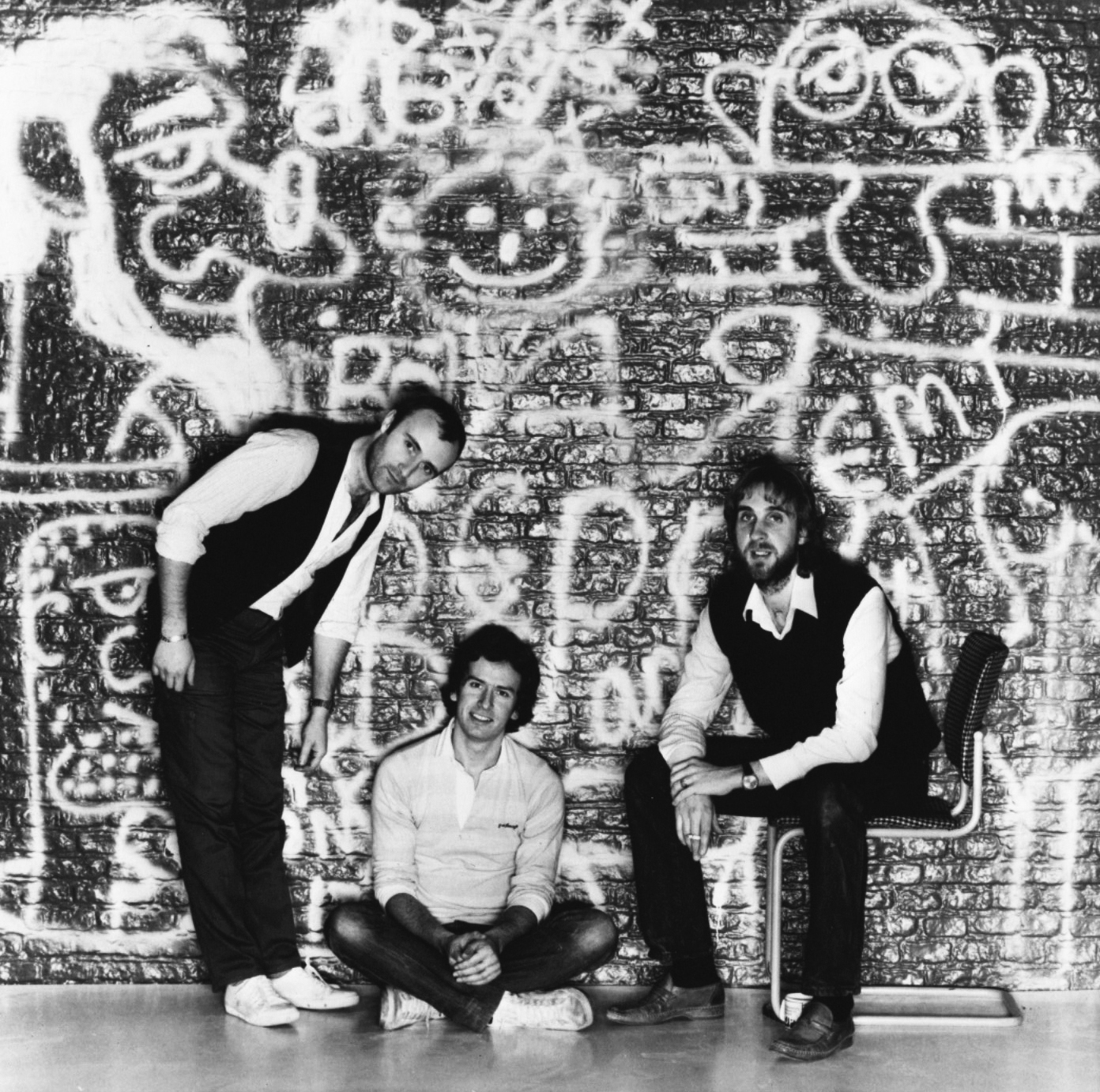

Bankstatement, 1989: Alistair Gordon, Jayney Klimek and Tony Banks | Photo: John Swannell

Bankstatement, 1989: Alistair Gordon, Jayney Klimek and Tony Banks | Photo: John Swannell

Bankstatement offered a more pop-oriented approach. Tell me about your desire to explore that territory more deeply in 1989.

I don't see it as being particularly pop, but I understand people saying that, I suppose. Having done The Fugitive and realizing I couldn't front a band, I wanted to try and get a sort of band together with permanent singers. Also, I wanted to work with a female singer again.

What I came up with at that point in time had a couple of pop things on it, but there were still some quite involved tracks which had that characteristic sort of Banks harmony, if you like. You’ll hear that on “That Night” and “The Border” in particular. I don’t see them being more pop than The Fugitive. I think the fact that I wasn’t singing on Bankstatement gave the album a slightly smoother feel. Alistair Gordan has quite a smooth voice, which I really liked.

I was very pleased with Bankstatement and the record company was too, but again, we couldn’t get a single played, so the album sort of died without a trace.

Provide some insight into the decision to use Bankstatement instead of your name for the album.

I wanted it to project a group idea. So, the Bankstatement thing was suggested because it’s a combination of phrases and it’s also a word we all know. It seemed to be a reasonable thing to use—it’s a statement from me. The idea was to take it a little away from me, but still have it be my project. Had It been successful, I suppose I could have gone out on tour as Bankstatement. But it wasn’t and we didn’t follow it up. I didn’t see any particular need to go the same route when I did the next album, so it ended up being a one-off.

What was it like to work with Steve Hillage as co-producer on Bankstatement?

Steve is one of a kind. I'm sure anyone who's worked with him will tell you the same thing. He gets very obsessed by certain things. We got on great in the end. We had a few problems along the way, which I think you often do in the studio. But I was pleased with the result, and I think we did a great job together.

The only problem was that he was supposed to be the guitarist on the album, but was going through a period when he didn't really feel that confident playing guitar. So, it was very difficult to encourage him to play much. I got him to play a little bit on a couple of tracks, which means the album is a bit guitar light. If I had known he was going to be coy about playing guitar, I would have got someone else in to do the guitar parts, because I think guitar adds so much to rock music. After the drums, it's the main ingredient really. I need the power that guitar provides.

Tony Banks and Nik Kershaw, 1991 | Photo: Carl Studna

Tony Banks and Nik Kershaw, 1991 | Photo: Carl Studna

Still from 1991 captured many different approaches. How do you look back at it?

I decided since I wasn't going to go for the group approach, that I would just make a record. At this point, I felt “I’m a songwriter. Let’s try and get the best singer we can for each song.” I used singers that I felt suited the songs. As I mentioned before, I rang up Nik Kershaw to see if he would be into it, and he was. But I knew he wasn't going to be right for all the songs. There were three I really thought he could sing well, but I looked elsewhere for other songs. I brought back Fish to sing, who I wanted to work with again. He wrote the lyrics for “Another Murder of a Day” and on the other one, "Angel Face," he sang my lyrics. He did a very good job on both.

Jayney Kilmek carried over from Bankstatement and sung on "Water Out of Wine" and “Back to Back” because I liked her voice very much. And then, the final guy was Andy Taylor, a singer who has nothing to do with Duran Duran. A lot of people think he was in it, but he wasn't. I wanted someone with a voice like Ray Charles, but I couldn’t find one at the time. So, I used Andy who wasn't really a great singer, but he had a sort of tone to his singing that worked quite well. I think the songs he sings, “The Gift” and “Still It Takes Me by Surprise” stand up with his voice. “Still It Takes Me by Surprise” is a very personal song for me. It’s one of the few times I’ve actually written a song from a personal viewpoint, rather than from an invented one.

Also, by this stage, in 1991, I was writing for the CD, which meant I had more time. You got an hour, rather than the 40-45 minute thing of the LP. So, I was able to get a greater variety of music on it. I think Still had elements in which I tried to stretch what I can do with harmony, particularly during the middle part of “The Final Curtain” where I let myself go a little bit. It’s one of my favorite bits on the record for that reason.

I also thought we had a hit with “I Wanna Change the Score,” but unfortunately we didn’t. Nik Kershaw, who sang on it, wasn’t very keen to do any promotion or television appearances, which didn’t help. What can one say? Maybe the song didn’t have it, but I hear it now and I still think it sounds like a hit. If it had been done by Genesis, it would have been a hit, let’s put it that way. Again, the album didn’t do quite what I hoped, but I loved making it.

Strictly Inc., 1995: Jack Hues and Tony Banks | Photo: David Scheinmann

Strictly Inc., 1995: Jack Hues and Tony Banks | Photo: David Scheinmann

Strictly Inc. from 1995 is your least well-known solo effort. Explore how that one came together.

It was the first time I’ve worked all the way through an album with a singer who was involved in more than just the singing. Kim Beacon sang on A Curious Feeling, but didn’t write lyrics. Jack Hues was involved in a couple of lyrics. He was also around quite a bit when I was making the album. He played guitar on some of the pieces, but didn’t want to do some of the lead guitar work. He was happy to do little bits and pieces and that worked well. So, Strictly Inc. was more of a unit with Jack and Nick Davis, who produced it.

I felt I’d written a lot of strong material for Strictly Inc., but I’m particularly happy with “An Island in the Darkness,” which was a long piece and I thought was the backbone of the album. Jack also sang a little bit the way I would want to sing if I could sing. I thought he sounded great on that track. I was really excited by Strictly Inc. and when we listened to it when it was completed, Jack said “Well, that’s fantastic. If this was the new Genesis album, everyone would be very happy.”

I felt I’d covered all bases on this album. It had some range and quality about it that made it special. Of course, I was trying to quietly shy away from me “being the man.” That’s why I put it out under the group name Strictly Inc. and course, for that reason, it didn’t do anything. People didn’t even know it was a Tony Banks album. I regret that the most about the project. I would have definitely liked it to have had a much higher profile.

What are some of the bigger challenges you've faced as a solo artist?

Getting an audience beyond the Genesis audience—or even a major part of the Genesis audience. That was the challenge I never managed to surmount.

With A Curious Feeling, I was a bit self-conscious about everything. I knew I couldn’t play drums, so I got Chester Thompson, who was a good friend and excellent drummer, to play on it. I got a singer who would just sing the songs and I tried to do everything else myself, including playing guitar and bass, which was quite a challenge. Acoustic guitar wasn’t a problem, but lead electric guitar was challenging. I just about carried that off.

Then there’s a question, each time, of trying to find a way of making these albums. I got more confident about involving other musicians as I went on. Daryl Stuermer, a fantastic musician, is someone I’ve used quite a lot on my solo albums. He was a great help when I did The Fugitive. He wrote out bar charts for the other musicians to follow. He played superb guitar on the whole album. I also had the world-class drummer Steve Gadd on the album. It was a really good experience from that point of view, because I’d also taken on the singing responsibilities, so I was doing more. I really only played keyboards and sang on that album.

After The Fugitive, I was happy to use other people much more. I felt confident enough in my own music that I could bring people in and not feel embarrassed about having them play on it. I was able to get people like Vinnie Colaiuta to play on Still and John Robinson to work on Strictly Inc. By the point of Strictly Inc., I was totally confident as a writer and understood what my role was and what I had to do. I stopped caring what everyone thought about the music and followed it through.

Genesis, 2007: Mike Rutherford, Phil Collins and Tony Banks | Photo: Stephanie Pistel

Genesis, 2007: Mike Rutherford, Phil Collins and Tony Banks | Photo: Stephanie Pistel

You’ve often stated you’re frustrated that your solo career never achieved the profile of Phil Collins or Mike Rutherford. Why was that a concern given the huge success of Genesis?

I just want to be loved! [laughs] But you're absolutely right. I'm very philosophical about this. Yes, I had fantastic success with Genesis—the sort of success most songwriters could only dream about, so I really don't want to over-emphasize the disappointment. But if you ask me, "Would I like to have been more successful as a solo artist?" The answer is “Yes.” I say that because I think a lot of the music on my solo albums is as good as the stuff I did with Genesis. So, I would like it to have had a higher profile. There isn't anything wrong in wanting that.

The salt was kind of rubbed in the wound by the success of Mike and the Mechanics. Phil’s stuff was successful because he’s a singer and all the rest of it. But with Mike and the Mechanics, it sort of made me feel like I was very much the third member. It would have helped just a little bit—for my own ego, I suppose—to have had solo success. It’s not a lasting problem at all for me. I had great hopes for some of the albums. But it was a bit disappointing and depressing to put out a record and hope something would happen with it and then not have it happen. I have to be honest about that. I can’t deny it.

I was particularly surprised with Strictly Inc., which didn’t get any attention at all. I don’t even think the fans bought it. It was a curious change, the way things went with that one.

What sort of record label support were you getting when you put out your solo rock albums?

They've always been helpful. I was with Charisma for A Curious Feeling. That's the one that did the best. It went okay. For The Fugitive, I was originally going to go with Stiff Records for it, but I kind of failed the interview with them. Once they met me, they realized I wasn’t the sort of person they felt they could really work with. So, I ended up on Charisma for that one as well, and they were good.

Jeremy Lascelles in A&R at Virgin suggested I work with Steve Hillage. Jeremy came along to a lot of the Bankstatement sessions and listened to stuff as it went down. He was very enthusiastic. They really wanted it to work, you know? But it didn’t.

Ever since Bankstatement, the record companies have been fine. One thing about being successful with Genesis meant I was always able to find someone to put my records out. Virgin was still interested in me for both Still and Strictly Inc. They didn’t spend the kind of money on them that they would have on Michael Jackson, but they put a certain amount of resources into them. But you can only do so much promotion if you’re not getting any response.

What’s your theory on why your rock albums didn’t connect with the mainstream?

I put it down to the fact that I never had a hit single. I'm not very good at promoting. I'm certainly no schmoozer. Mike Rutherford, for all his talents, is quite a good schmoozer, which does help. If you can do that, you can meet and get on with people, and these things make everything a little bit easier. With me, I always put the albums out into the dark, in my own sort of way.

But I don’t really know why nothing connected. As I said earlier, "I Wanna Change the Score" with Nik Kershaw felt like a potential hit. The record company was very keen on it. But at some point, being the keyboard player for Genesis become no asset to my promotion. If you’re the singer of a great band, you automatically start off with a kind of advantage. People know your voice and you already have a profile. And then if you come up with something as good as Phil did with Face Value, you’re winning. From then on, your career is set.

Mike was very clever. Mike and the Mechanics seemed to work right from the word go. He seemed to have that edge that got him that attention, with music that was kind of radio friendly.

Tony Banks at Genesis' Fisher Lane Farm Studios, Chiddingfold, Surrey, England, 2015

Tony Banks at Genesis' Fisher Lane Farm Studios, Chiddingfold, Surrey, England, 2015

Your last three solo albums have been classical music projects. Describe the ambitions they fulfilled for you.

After the relative lack of success of Genesis’ Calling All Stations, I was going to be 50. I thought “Well, maybe that’s it. Maybe it’s time to either do something else or do nothing.” I’d done all these solo albums and not had much success. Genesis looked like it was fading away. So, what was I going to do?

Over the years, people have said they liked the second half of The Wicked Lady soundtrack, which was performed by The National Philharmonic Orchestra. The main theme sounded so much better with an orchestra than it did when it was just played on piano. So, I thought, before I give up, let’s see if I can get an orchestral project together.

I sat down and tried to write a few things, such as "Black Down” for Seven, which I think is far and away the best piece on it. After I wrote it, I thought “I’ve really got to try and get this happening so I can record this piece, if nothing else.” I wrote a few other pieces, got together a couple of others from my past, arranged them in an orchestral way, and got in touch with a record company. They wanted to do it, so we arranged it with everybody and we went into the studio with the London Philharmonic Orchestra, which you can hire, just like anybody else.

One of the first sessions didn’t go very well. Nothing sounded very good. I came out of it very disappointed and disillusioned. I thought “Maybe I won’t do this after all.” But then I had some encouragement from others who said “No, you’ve really got to go through with this.” So, I got together with Nick Davis, who’s someone I’ve obviously worked with a lot before. He was a real help. We tried to do it a different way. We went into the next session with a really positive mood and thought we’d see what happens. It made a lot of difference. I had another conductor named Mike Dixon involved at that point who was much more conducive to this sort of project. The previous one was a very classical conductor and he was fine as a conductor, but didn’t really understand what I was trying to do, whereas Mike did.

And so, we ended up with Seven in 2004, which I was very excited about. Curiously, it got quite a lot of good reviews and achieved reasonable success—much more so than my rock albums had ever done. So, I thought “I could go on with this.” And I did. I’ve done two more since: Six Pieces for Orchestra and 5.

In some ways, I wasn’t sure I’d do the second one, but I kept being asked during the Genesis revival tour in 2007 “What are you going to do next, Tony?” And I kept saying “Well, maybe I’ll do another classical album” because I had to have something to say. And because Phil and Mike seemed to know what they were doing next. So, I went forward with that. I was more confident going in to make Six Pieces for Orchestra in 2011. I decided to record in Prague with the City of Prague Philharmonic Orchestra, conducted by Paul Englishby. They were better suited to what I was trying to do. The London Philharmonic Orchestra was kind of snooty towards me and incredibly expensive. In Prague, I could have rehearsal time and work with people who actually had enthusiasm for the stuff. It resulted in a better album.

For 5, the most recent classical recording, I did it much more like a rock album. I started off with my piano parts, then added to them and layered them up. I really wanted to try and control every aspect of it, including the tempo. I wanted to get the orchestra to do it how I wanted to do it. I worked with the Czech National Symphony Orchestra and Choir, and conductor Nick Ingman on it.

I think the album works. I don’t think it sounds like it was put together the way I did it. With the first two classical albums, I felt they had moments which were great—sometimes those were serendipitous moments on songs in which things came out better than I thought they would. But there were also other bits that weren’t as good. With 5, it’s pretty much exactly how I intended it to be. If you don’t like it, it’s still what I intended. [laughs] I feel quite pleased with it. I love the album and think it's one of the best I’ve ever done. It did very well for about a week in England and then things kind of went blank. But overall, these albums seemed to reach people I wasn’t able to reach before and that, to me, is very exciting.

Genesis, 1997: Mike Rutherford, Ray Wilson and Tony Banks | Photo: Kevin Westenberg

Genesis, 1997: Mike Rutherford, Ray Wilson and Tony Banks | Photo: Kevin Westenberg

How do you look back at the Calling All Stations era of Genesis from 1997-1998?

The album was an interesting thing. Obviously, if it had been a fantastic success, I’d probably be as happy with it as anything else we did. Mike was very keen to do the album the way we used to do it as a three-piece band with Phil, but now only as a two-piece with him and me. We were very reliant on drum machines. In the old days with Phil, we used to all be playing away at the same time and then things would emerge. Whereas without Phil, one person had to hold down a rhythmic pattern while the other person was improvising and that was more difficult to do.

I think we produced some very good songs for the album. I wanted to include one or two more solo-type things in there both from Mike and me. I loved the more “Ripples”-type things that Mike might do and the more adventurous “One for the Vine”-type things I might do. But Mike wasn’t keen to do that, so we ended up doing a certain kind of thing for the album. I think the album has a kind of uniformity about it that I regret. It contains one or two rather weak tracks, too. We also left off two of the strongest tracks, which was a mistake.

All in all, I wasn’t dissatisfied with the album. In Ray Wilson, we had a voice that was really good, but we really didn’t know he was the singer until later on in the process, so that kind of set us back a little bit. We listened to various tapes and got various people in to audition. Ray has a great voice, but it’s kind of got one real strength and it’s not so good for certain kinds of things.

Perhaps we should have gone for two singers. But when we let Ray have his reins, like on the title track and “There Must Be Some Other Way,” he really sounds strong. Those are two of the better tracks.

I felt I really missed having a singer like Phil who could improvise and have things emerge from that. I obviously missed his drumming too, although Nir Z., who we used on the album and tour, was really good.

An example of where things didn’t really work was the final part of “One Man’s Fool.” The first half sounds great, but the second part is unformed and doesn’t do what it should have done. I think if we’d been a band and written that, we’d have produced something better.

So, there you go. It’s good in parts and very good in other parts. But it has a few moments that are perhaps less good.

Funnily enough, Mike was very keen to do Calling All Stations and I was less keen. I said “Well, you know, without Phil, how’s it going to be? And the audience is going to be troublesome.” Everyone identified the group with Phil. Anyhow, after doing it, I was quite keen to do a second album, because I felt we finally understood Ray’s voice. We had a great drummer in Nir Z. and Anthony Drennan on guitar, who we really liked. I thought “Why don’t we go into the studio as a band and do it like that? Let’s see what happens.” But Mike had cold feet. He felt that Calling All Stations hadn’t been as successful as he had hoped and it was very disappointing. That especially was true for America. Mike felt it was best to knock it on the head. And thinking about it now, I believe he was right. It would have been a pity to do a couple more records which didn’t really stand up. We had done one that perhaps didn’t stand up. Doing a second one might have been the wrong decision.

As I mentioned, at that point, I considered leaving the music business totally. But that’s when I got involved in classical music and it took me into a totally different direction, which reinvigorated me.

I’d like to name some lesser-known Genesis songs and have you tell me the first thing that comes to mind.

Sure. Fire away.

“The Dividing Line” (Calling All Stations, 1997).

It has a great rhythm track, but lyrically, it’s a little bit simplistic. Melodically, it could have been better. But it was great fun to do the rhythm part. It has great drumming throughout, and particularly during the drum solo.

“Feeding the Fire” (Invisible Touch b-side, 1986).

It’s a little bit Tears For Fears-y. I think it’s a strong song and I was rather pleased with the lyric. The basic riff is really good. I liked using the idea of “feeding the fire” as a way of describing how people cause their own downfall. I’d quite like to have had it on the album, but there were a lot of choices to make.

“The Brazilian” (Invisible Touch, 1986) and “Do the Neurotic” (Invisible Touch b-side, 1986).

There’s always been a bit of a thing about these instrumental tracks. A lot of people felt we should have put “Do the Neurotic” on Invisible Touch and not “The Brazilian.” We put “The Brazilian” on it because we liked the quirkiness of it. It’s a much simpler piece than “Do the Neurotic.” I think “Do the Neurotic” is the wildest thing we ever did. I listened to it the other day. It’s incredibly complicated and has some really wild moments. You have to remember we were really playing these songs. There was no kind of cheating going on there, in which someone might have been dropping things in after the fact. I think “Do the Neurotic” is probably the best we ever played together as a unit and it sounds really, really good. Given that we were only a three-piece, it’s a very exciting piece of music. Looking back at it, I would have preferred it to have been on the album. But Torvill and Dean danced to “The Brazilian,” so it can’t be all bad.

Genesis, 1981: Phil Collins, Tony Banks and Mike Rutherford | Photo: Gered Mankowitz

Genesis, 1981: Phil Collins, Tony Banks and Mike Rutherford | Photo: Gered Mankowitz

“Keep It Dark” (Abacab, 1981).

A favorite of mine. I wrote the lyric. People might say “Because you wrote the lyric, therefore you like it for that reason.” [laughs] The song has incredible simplicity. We had a drum loop and a guitar riff that sort of goes throughout the whole piece. I decided I’d try and make as many chord changes work with this very simple riff as I possibly could. So, it goes through quite a few of them.

It has an incredibly romantic chorus with a stark kind of lyric. I thought “How do I contrast that with the lyric?” So, the idea of the verse about the guy saying what had actually happened to him came up. He’d taken off in a space ship and seen this whole other wonderful, beautiful world. But he could never tell anyone about it because they’d all think he was mad. I rather like that idea—no-one believing you’ve been taken away by aliens. Everyone would laugh at you. So, if it happened to you, best to keep it to yourself—that’s why it’s called “Keep It Dark.”

“Naminanu” and “Submarine” (Abacab b-sides, 1981).

Both of those instrumental pieces didn’t get on the album but I really love them. There’s a moment in “Naminanu” when it really takes off and goes into double time at the end. The whole thing’s building to that. The track can maybe be a bit irritating and repetitive, but I found it quite exciting. It would have been part of a longer piece if we had decided to go that route.

There was a possibility of “Dodo/Lurker” to have gone into other bits and pieces like “Naminanu” and “Submarine” on the album, but we decided in the end not to do that. We thought we should go the shorter, more direct route.

Abacab was definitely a kind of break for us. We got away from the big choruses and went somewhere else that was a little bit more straight-ahead. We also had these great drum sounds that Phil had cultivated, particularly with Peter Gabriel on “Intruder” and later on Face Value. It was such a big sound and so exciting in and of itself. We almost didn’t need to put all those big keyboards in there. So, that was the approach for Abacab. We went small and junked everything apart from the drums. I think it was quite successful from that point of view.

“Duchess” (Duke, 1980).

We’re back to another lyric I wrote. I’ve often said it’s my favorite Genesis song. It’s been resurrected a few times over the years. Rosanna Arquette told me it was her favorite song. I think listeners can relate to it in a lot of different ways. You don’t have to be a singer to relate to the idea of a rise and fall in a person’s career.

“Duchess” was just a name for a female singer. It was a single-word name to represent her. The song talks about her starting off with a desire for success, then her achieving success, and then things going wrong for her at the end. It’s a career arc if you will. I think a lot of careers have this kind of shape. The song could have just as easily been about Genesis itself.

The one thing about a rock song—and it’s why romantic songs are so successful, is that simple directness. It you get that right in a song, it’s incredibly powerful. If you look at the lyrics for “Duchess” on paper, they’re nothing. But when you combine it with the music, it becomes something very, very strong. The song has a sort of flavor that’s universal.

"One for the Vine” (Wind & Wuthering, 1976).

Well, you're picking all songs in which I wrote the lyrics, aren't you? With this one, I wrote the whole thing. This was during the stage in which I’d just play a whole song to the other guys as they were working on it. What we’d do is first put it down in the studio with just me and Phil. I’d sit down on the piano and Phil would be on drums. And then we’d do all the overdubbing on it.

I think it turned out pretty good and it got better live. It would have been nice if we could have rehearsed it a bit more before recording it. But the way we did it gave everyone a chance to be a bit quirky, particularly with Phil’s drumming and Steve’s imaginative playing. I think Steve sounds really good doing all the little bits and pieces he does on it.

The song was a bit like a mini-suite at 10 minutes with quite a strong, dramatic ending. Lyrically, I think it was similar to “The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway.” It’s about a person who becomes the thing he originally despised—a sort of messiah-like figure. At the end, he’s disillusioned with it, which is probably quite true in a lot of walks of life, particularly politics.

Genesis' first publicity photo, 1969: Anthony Phillips, Mike Rutherford, Tony Banks, Peter Gabriel, and Chris Stewart

Genesis' first publicity photo, 1969: Anthony Phillips, Mike Rutherford, Tony Banks, Peter Gabriel, and Chris Stewart

“Where the Sour Turns to Sweet" (From Genesis to Revelation, 1969).

Now you’re really going back in time. Peter Gabriel and I wrote this song a long, long time ago. It first had a different chorus, which wasn’t as good as the one we ended up with. We decided in the end to make a chorus out of the introduction, which made it a much better piece of music.

This was the fourth piece of music we ever wrote together. In those days, it used to be very much me playing along on the piano with Pete singing along on top. Pete would get his hands on the piano whenever he could.

When I hear this song, it takes me right back to those early days with Anthony Phillips and everybody else. We were very naïve back then. We’d all come from a very sheltered background and didn’t know much about anything, really. So, what we came up with is a rather sweet kind of piece, with a strong chorus. It probably hinted at what we might do later on. We were definitely thinking in different terms during those early days.

Collins is once again active as a touring musician. And last June, Rutherford performed “Follow You, Follow Me” with him in Berlin. Have the three of you discussed a Genesis reunion?

We occasionally talk about it. I never thought Phil would actually be able to perform like he is now and for this length of time. So, the possibility is obviously there now. It would be very different, though. Phil can’t drum. His son Nic Collins is an excellent drummer and is able to play in a style very similar to Phil, but there would still be quite a few logistical problems in how we’d do it, if we were to do it.

But we do talk about it. I won’t say it’s impossible. As Mike always says “Never say never.” We carry on saying that. It’s certainly more likely now than it was two or three years ago, when I didn’t think Phil would ever be able to perform again. But now that he is performing and sounding great singing, it must be a possibility, I suppose. But we have no plans. We haven’t talked about it in any definitive terms. I don’t want to get people’s hopes up, but the idea does come up.

How would you envision how a Genesis show would work with Collins seated throughout and his son on drums?

Well, of course it can work, but it’ll be kind of different. Phil used to have some very dramatic moments on stage with Genesis. He’d never have the same kind of dramatic moments or intensity we used to have with “Domino,” “Home by the Sea” or “Afterglow” sitting on a chair. Obviously, the effects can help things out a bit.

So, you just say “He’s not going to do those the same way.” We’d just do the songs. We’ve got plenty of good songs to do and it wouldn’t be a problem. But I don’t think we could have the extended keyboard solo we did on the last tour in 2007 which had a bit of everything in it. There wouldn’t be much point, because the point of it was Mike, Phil and I playing together, like we did on things such as “Duke’s Travels.” There would be a different intensity and a different kind of set list. But I can’t see any reason for why it can’t be done If everyone’s health is reasonable and the inclination is there.

Photo: Emily Banks

Photo: Emily Banks

Do you miss performing to giant crowds with Genesis?

No. I don't have the craving. But I would do it, because I can't see any reason not to do it. And it's what I am. I'm a rock musician, essentially. Hopefully, I'm a songwriter, and also a music writer as well. I think there's a part of it that's exciting, too. When I go to someone else's gig and I go backstage, I get that feeling again.

When we did the last tour in 2007, it wasn’t just about the band members, including Daryl Stuermer and Chester Thompson, but also the crew. There was a great feeling, being together with all the wives and children and seeing how the kids have grown up. It was a lovely moment. We had nothing to prove, which was great. There was no new material, so we just played the music. If you didn’t like us, you didn’t come. If you liked us, you did. The audience had the ability to hear songs they wanted to hear and maybe songs they didn’t want to hear. But hopefully, we played enough people wanted to hear that we made it worthwhile.

So, I don’t think “Well, we don’t want to do that again.” It is exciting to go out there and play in front of big crowds, I can’t deny it. I’ve always felt a bit of a spectator to it. I feel the crowd and how they respond to the music. I’m the man in the middle of it and that’s how it should be. There’s no doubt it’s a thrill.

What does the future hold for you as a musician?

I don't know. I really don't. There are all sorts of possibilities. One option is doing another classical thing. I also want to do another rock thing. There are also other little projects I’ve done as well, which have been quite fun, like my work with John Potter. In 2015, I contributed to his album Amores Pasados on ECM. He’s a classical tenor. I wrote two settings for poems which ended up on the album. I’ve done another two, which hopefully will end up on a future record. There’s no pressure when doing them. He does what he wants with them and they come out very nice.

I was able to write these things very quickly, because I already had the lyric, which was quite a bonus. It taught me why Elton John was able to knock out tracks so quickly—it’s because he already had the lyrics from Bernie Taupin. It sets the whole mood in motion. It’s quite an interesting and enjoyable thing to do.

I like doing things in which I’m not the man. I would have really liked to have just been a writer and have other people sell my music, rather than have to go out there and do it myself. But that was never meant to be.

Is there a spiritual component to your music?

No, not really, I'm afraid. I'm an earthbound man. What I can say is my whole experience of music is very pure. I hear music as music. I don’t hear it in any other way. So, I try not to analyze it. If I do, then it becomes something else. When I don’t analyze music, there’s something going on in my brain that is completely unrelated to anything physical. It’s something totally outside of that.

I can have trouble adding lyrics to a song when I start out with an instrumental piece and a title. The title always tends to give character to the song. For the album Seven, I wanted to call the pieces “One,” “Two,” “Three,” “Four,” “Five,” “Six,” and “Seven,” but the label wouldn’t let me. I wanted to try and totally get away from any character being instilled in the music from the title.

A favorite piece of mine, Shostakovich's “Symphony No. 10” doesn’t really have any titles for its pieces. So, when you listen to it, you can just be there. It’s just music and it’s wonderful. You can experience the music just on that level. I love that. I want people to have the same experience with my work, which is just totally of music.